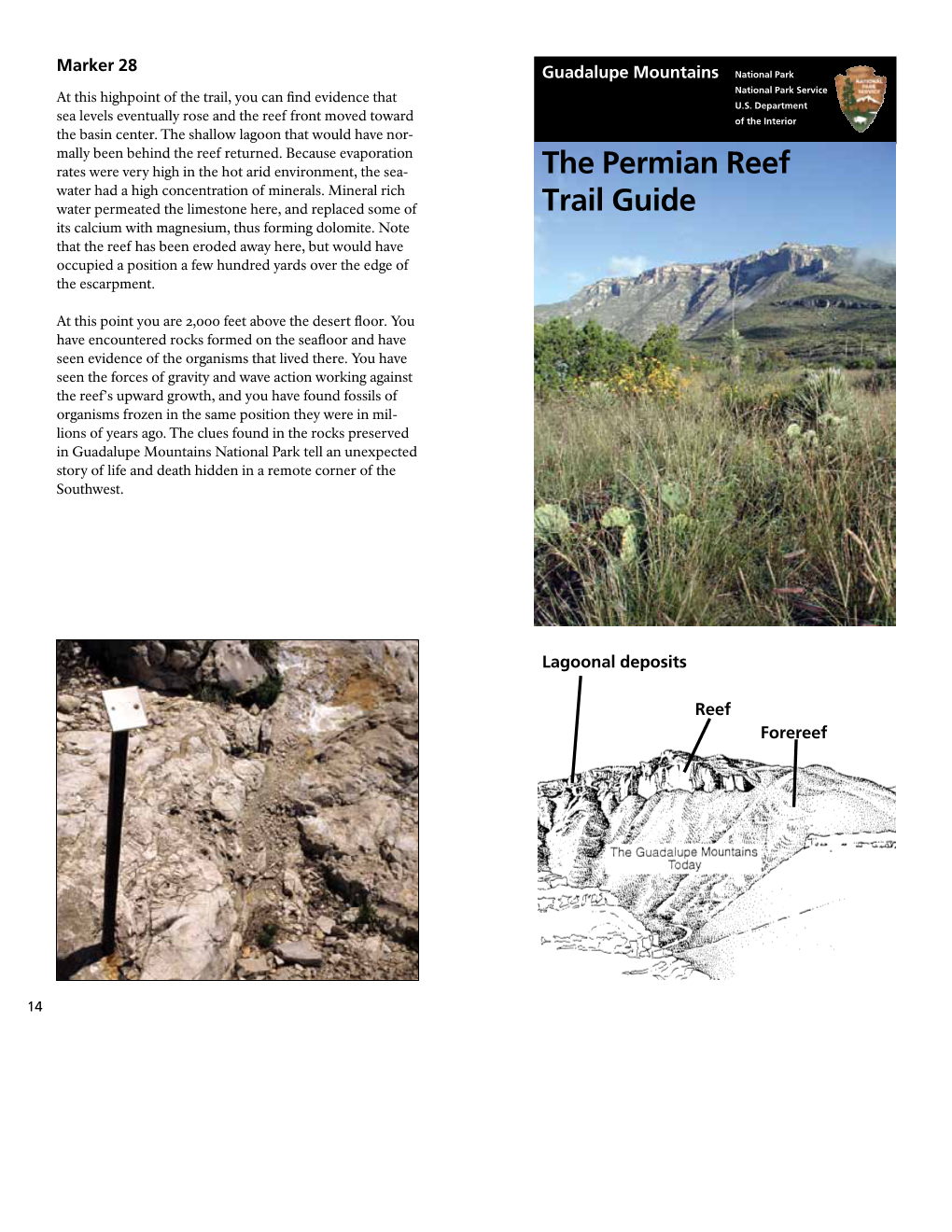

Permian Reef Water Had a High Concentration of Minerals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geologic Time Scale Cards

PreCambrian SuperEon (4.6 BYA – 541 MYA) Hadean Eon (4.6 BYA - 4 BYA) Slide # 1 46 feet Earth Forms • Earth is formed from a mass of dust and gas that gravity pulled together. • The process causes a huge amount of radioactive decay and Earth is a boiling ball of lava. • At 4.5 BYA a protoplanet named Theia collides with Earth and a debris ring forms which later becomes our moon. • Earth cools and forms the layers – core, mantel, and outer crust. • Meteors bombard earth bringing frozen droplets of water that later become our oceans. • Volcanic activity continues and Earth’s earliest continental crust forms before 4.03 BYA. The Acasta gneiss is one of the oldest rocks on Earth dating 4.03 billion years.. PreCambrian SuperEon (4.6 BYA – 541 MYA) Archaean Eon (4 BYA – 2.5 BYA) Slide # 2 40 feet Primitive, Simple Life Forms • Earth’s crust cools and plate tectonics forms. • Ancient rock formations form from 4 to 2.5 BYA. • The Primordial soup theory suggests early minerals and compounds from meteors made the perfect recipe for primitive, simple life to form at the thermal vents of the ocean. • Single cell life formed the ocean and over time stromatolites, photosynthesizing colonial bacteria, formed in shallow water and released oxygen. • The oxygen attached to trace iron in the oceans and formed sedimentary layers of banded iron formations (BIFS) that are presently mined for iron ore. Banded iron formations from the late Archaean and early Proterozoic eons Stromatolite fossil image PreCambrian SuperEon (4.6 BYA – 541 MYA) Proterozoic Eon (2.5 BYA – 541 MYA) Slide # 3 25 feet Early life • Photosynthesizing life further establishes and releases oxygen throughout the ocean. -

PERMIAN BASIN PROVINCE (044) by Mahlon M

PERMIAN BASIN PROVINCE (044) By Mahlon M. Ball INTRODUCTION The Permian Basin is one of the largest structural basins in North America. It encompasses a surface area in excess of 86,000 sq mi and includes all or parts of 52 counties located in West Texas and southeast New Mexico. Structurally, the Permian Basin is bounded on the south by the Marathon-Ouachita Fold Belt, on the west by the Diablo Platform and Pedernal Uplift, on the north by the Matador Arch, and on the east by the Eastern Shelf of the Permian (Midland) Basin and west flank of the Bend Arch. The basin is about 260 mi by 300 mi in area and is separated into eastern and western halves by a north-south trending Central Basin Platform. In cross section, the basin is an asymmetrical feature; the western half contains a thicker and more structurally deformed sequence of sedimentary rock. The Permian Basin has been characterized as a large structural depression formed as a result of downwarp in the Precambrian basement surface located at the southern margin of the North American craton. The basin was filled with Paleozoic and, to a much lesser extent, younger sediments. It acquired its present structural form by Early Permian time. The overall basin is divisible into several distinct structural and tectonic elements. They are the Central Basin Platform and the Ozona Arch, which separate the Delaware and Val Verde Basins on the south and west from the Midland Basin on the north and east, the Northwestern Shelf on the southern extremity of the Pedernal Uplift and Matador Arch, and the Eastern Shelf on the western periphery of the Bend Arch. -

The Geologic Time Scale Is the Eon

Exploring Geologic Time Poster Illustrated Teacher's Guide #35-1145 Paper #35-1146 Laminated Background Geologic Time Scale Basics The history of the Earth covers a vast expanse of time, so scientists divide it into smaller sections that are associ- ated with particular events that have occurred in the past.The approximate time range of each time span is shown on the poster.The largest time span of the geologic time scale is the eon. It is an indefinitely long period of time that contains at least two eras. Geologic time is divided into two eons.The more ancient eon is called the Precambrian, and the more recent is the Phanerozoic. Each eon is subdivided into smaller spans called eras.The Precambrian eon is divided from most ancient into the Hadean era, Archean era, and Proterozoic era. See Figure 1. Precambrian Eon Proterozoic Era 2500 - 550 million years ago Archaean Era 3800 - 2500 million years ago Hadean Era 4600 - 3800 million years ago Figure 1. Eras of the Precambrian Eon Single-celled and simple multicelled organisms first developed during the Precambrian eon. There are many fos- sils from this time because the sea-dwelling creatures were trapped in sediments and preserved. The Phanerozoic eon is subdivided into three eras – the Paleozoic era, Mesozoic era, and Cenozoic era. An era is often divided into several smaller time spans called periods. For example, the Paleozoic era is divided into the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous,and Permian periods. Paleozoic Era Permian Period 300 - 250 million years ago Carboniferous Period 350 - 300 million years ago Devonian Period 400 - 350 million years ago Silurian Period 450 - 400 million years ago Ordovician Period 500 - 450 million years ago Cambrian Period 550 - 500 million years ago Figure 2. -

The Parallels Between the End-Permian Mass Extinction And

Drawing Connections: The Parallels Between the End-Permian Mass Extinction and Current Climate Change An undergraduate of East Tennessee State University explains that humans’ current effects on the biosphere are disturbingly similar to the circumstances that caused the worst mass extinction in biologic history. By: Amber Rookstool 6 December 2016 About the Author: Amber Rookstool is an undergraduate student at East Tennessee State University. She is currently an English major and dreams of becoming an author and high school English Teacher. She hopes to publish her first book by the time she is 26 years old. Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................1 Brief Geologic Timeline ...........................................................................................................2 The Anthropocene ......................................................................................................................3 Biodiversity Crisis ....................................................................................................................3 Habitat Loss .........................................................................................................................3 Invasive Species ..................................................................................................................4 Overexploitation ...................................................................................................................4 -

Guadalupian, Middle Permian) Mass Extinction in NW Pangea (Borup Fiord, Arctic Canada): a Global Crisis Driven by Volcanism and Anoxia

The Capitanian (Guadalupian, Middle Permian) mass extinction in NW Pangea (Borup Fiord, Arctic Canada): A global crisis driven by volcanism and anoxia David P.G. Bond1†, Paul B. Wignall2, and Stephen E. Grasby3,4 1Department of Geography, Geology and Environment, University of Hull, Hull, HU6 7RX, UK 2School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK 3Geological Survey of Canada, 3303 33rd Street N.W., Calgary, Alberta, T2L 2A7, Canada 4Department of Geoscience, University of Calgary, 2500 University Drive N.W., Calgary Alberta, T2N 1N4, Canada ABSTRACT ing gun of eruptions in the distant Emeishan 2009; Wignall et al., 2009a, 2009b; Bond et al., large igneous province, which drove high- 2010a, 2010b), making this a mid-Capitanian Until recently, the biotic crisis that oc- latitude anoxia via global warming. Although crisis of short duration, fulfilling the second cri- curred within the Capitanian Stage (Middle the global Capitanian extinction might have terion. Several other marine groups were badly Permian, ca. 262 Ma) was known only from had different regional mechanisms, like the affected in equatorial eastern Tethys Ocean, in- equatorial (Tethyan) latitudes, and its global more famous extinction at the end of the cluding corals, bryozoans, and giant alatocon- extent was poorly resolved. The discovery of Permian, each had its roots in large igneous chid bivalves (e.g., Wang and Sugiyama, 2000; a Boreal Capitanian crisis in Spitsbergen, province volcanism. Weidlich, 2002; Bond et al., 2010a; Chen et al., with losses of similar magnitude to those in 2018). In contrast, pelagic elements of the fauna low latitudes, indicated that the event was INTRODUCTION (ammonoids and conodonts) suffered a later, geographically widespread, but further non- ecologically distinct, extinction crisis in the ear- Tethyan records are needed to confirm this as The Capitanian (Guadalupian Series, Middle liest Lopingian (Huang et al., 2019). -

Sequence Biostratigraphy of Carboniferous-Permian Boundary

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2019-07-01 Sequence Biostratigraphy of Carboniferous-Permian Boundary Strata in Western Utah: Deciphering Eustatic and Tectonic Controls on Sedimentation in the Antler-Sonoma Distal Foreland Basin Joshua Kerst Meibos Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Meibos, Joshua Kerst, "Sequence Biostratigraphy of Carboniferous-Permian Boundary Strata in Western Utah: Deciphering Eustatic and Tectonic Controls on Sedimentation in the Antler-Sonoma Distal Foreland Basin" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 7583. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/7583 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Sequence Biostratigraphy of Carboniferous-Permian Boundary Strata in Western Utah: Deciphering Eustatic and Tectonic Controls on Sedimentation in the Antler-Sonoma Distal Foreland Basin Joshua Kerst Meibos A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Scott M. Ritter, Chair Brooks B. Britt Sam Hudson Department of Geological Sciences Brigham Young University Copyright © 2019 Joshua Kerst Meibos All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Sequence Biostratigraphy of Carboniferous-Permian Boundary Strata in Western Utah: Deciphering Eustatic and Tectonic Controls on Sedimentation in the Antler-Sonoma Distal Foreland Basin Joshua Kerst Meibos Department of Geological Sciences, BYU Master of Science The stratal architecture of the upper Ely Limestone and Mormon Gap Formation (Pennsylvanian-early Permian) in western Utah reflects the interaction of icehouse sea-level change and tectonic activity in the distal Antler-Sonoma foreland basin. -

A Fundamental Precambrian–Phanerozoic Shift in Earth's Glacial

Tectonophysics 375 (2003) 353–385 www.elsevier.com/locate/tecto A fundamental Precambrian–Phanerozoic shift in earth’s glacial style? D.A.D. Evans* Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University, P.O. Box 208109, 210 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, CT 06520-8109, USA Received 24 May 2002; received in revised form 25 March 2003; accepted 5 June 2003 Abstract It has recently been found that Neoproterozoic glaciogenic sediments were deposited mainly at low paleolatitudes, in marked qualitative contrast to their Pleistocene counterparts. Several competing models vie for explanation of this unusual paleoclimatic record, most notably the high-obliquity hypothesis and varying degrees of the snowball Earth scenario. The present study quantitatively compiles the global distributions of Miocene–Pleistocene glaciogenic deposits and paleomagnetically derived paleolatitudes for Late Devonian–Permian, Ordovician–Silurian, Neoproterozoic, and Paleoproterozoic glaciogenic rocks. Whereas high depositional latitudes dominate all Phanerozoic ice ages, exclusively low paleolatitudes characterize both of the major Precambrian glacial epochs. Transition between these modes occurred within a 100-My interval, precisely coeval with the Neoproterozoic–Cambrian ‘‘explosion’’ of metazoan diversity. Glaciation is much more common since 750 Ma than in the preceding sedimentary record, an observation that cannot be ascribed merely to preservation. These patterns suggest an overall cooling of Earth’s longterm climate, superimposed by developing regulatory feedbacks -

THE PERMIAN-TRIASSIC SUPERNOVA IMPACT. C. H. Detre1, I

62nd Annual Meteoritical Society Meeting 5033.pdf THE PERMIAN-TRIASSIC SUPERNOVA IMPACT. C. H. Detre1, I. Tóth2, G. Don1, Á. Z. Kiss3, I. Uzonyi3, P. Bodó4, and Z. Schléder4, 1Geological Institute of Hungary, Stefánia út 14, H-1143 Budapest, Hungary, 2Konkoly Observatory, P.O. Box 67, H-1525 Budapest, Hungary, 3Institute for Nuclear Research, ATOMKI, P.O. Box 51, H- 4001 Debrecen, Hungary, 4Eötvös L. University, Department of Petrology and Geochemistry, Múzeum krt 4/a, H-1088 Budapest, Hungary. The end of the Permian has been one of the most tran- productive biomass of the recent time. From the outset quil epochs of the Earth’s history; from that time no of the Triassic the formation of carbonate rocks is on a powerful orogenic movements, no volcanism of con- leap-like increase : the rate of their Post-Triassic ac- siderable importance - save the effusion of the Siberian cumulation is approximately by an order of magnitude plateau-basalts - are known and also there are no higher as it has been before. It seems to be a satisfac- traces of the impact of some bigger celestial body like tory explanation for this development, that the amount a great meteorite, a core of a comet or some micro- of C consumed earlier by living organisms accumu- planet. The Permian-Triassic boundary as it is under- lated henceforth in the lithosphere. stood in traditional sense was the time of the renais- The spherules of interstellar origin, which can be sance of organic life. The crisis lasted approximately found in the Late Permian deposits provide a rather 20 million years during the Late Permian. -

Permian–Triassic Non-Marine Algae of Gondwana—Distributions

Earth-Science Reviews 212 (2021) 103382 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth-Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Review Article Permian–Triassic non-marine algae of Gondwana—Distributions, natural T affinities and ecological implications ⁎ Chris Maysa,b, , Vivi Vajdaa, Stephen McLoughlina a Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden b Monash University, School of Earth, Atmosphere and Environment, 9 Rainforest Walk, Clayton, VIC 3800, Australia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The abundance, diversity and extinction of non-marine algae are controlled by changes in the physical and Permian–Triassic chemical environment and community structure of continental ecosystems. We review a range of non-marine algae algae commonly found within the Permian and Triassic strata of Gondwana and highlight and discuss the non- mass extinctions marine algal abundance anomalies recorded in the immediate aftermath of the end-Permian extinction interval Gondwana (EPE; 252 Ma). We further review and contrast the marine and continental algal records of the global biotic freshwater ecology crises within the Permian–Triassic interval. Specifically, we provide a case study of 17 species (in 13 genera) palaeobiogeography from the succession spanning the EPE in the Sydney Basin, eastern Australia. The affinities and ecological im- plications of these fossil-genera are summarised, and their global Permian–Triassic palaeogeographic and stra- tigraphic distributions are collated. Most of these fossil taxa have close extant algal relatives that are most common in freshwater, brackish or terrestrial conditions, and all have recognizable affinities to groups known to produce chemically stable biopolymers that favour their preservation over long geological intervals. -

A New Late Permian Burnetiamorph from Zambia Confirms Exceptional

fevo-09-685244 June 19, 2021 Time: 17:19 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 24 June 2021 doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.685244 A New Late Permian Burnetiamorph From Zambia Confirms Exceptional Levels of Endemism in Burnetiamorpha (Therapsida: Biarmosuchia) and an Updated Paleoenvironmental Interpretation of the Upper Madumabisa Mudstone Formation Edited by: 1 † 2 3,4† Mark Joseph MacDougall, Christian A. Sidor * , Neil J. Tabor and Roger M. H. Smith Museum of Natural History Berlin 1 Burke Museum and Department of Biology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States, 2 Roy M. Huffington (MfN), Germany Department of Earth Sciences, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, TX, United States, 3 Evolutionary Studies Institute, Reviewed by: University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 4 Iziko South African Museum, Cape Town, South Africa Sean P. Modesto, Cape Breton University, Canada Michael Oliver Day, A new burnetiamorph therapsid, Isengops luangwensis, gen. et sp. nov., is described Natural History Museum, on the basis of a partial skull from the upper Madumabisa Mudstone Formation of the United Kingdom Luangwa Basin of northeastern Zambia. Isengops is diagnosed by reduced palatal *Correspondence: Christian A. Sidor dentition, a ridge-like palatine-pterygoid boss, a palatal exposure of the jugal that [email protected] extends far anteriorly, a tall trigonal pyramid-shaped supraorbital boss, and a recess †ORCID: along the dorsal margin of the lateral temporal fenestra. The upper Madumabisa Christian A. Sidor Mudstone Formation was deposited in a rift basin with lithofacies characterized orcid.org/0000-0003-0742-4829 Roger M. H. Smith by unchannelized flow, periods of subaerial desiccation and non-deposition, and orcid.org/0000-0001-6806-1983 pedogenesis, and can be biostratigraphically tied to the upper Cistecephalus Assemblage Zone of South Africa, suggesting a Wuchiapingian age. -

An Abrupt Extinction in the Middle Permian (Capitanian) of the Boreal Realm (Spitsbergen) and Its Link to Anoxia and Acidification

An abrupt extinction in the Middle Permian (Capitanian) of the Boreal Realm (Spitsbergen) and its link to anoxia and acidification David P.G. Bond1,†, Paul B. Wignall2, Michael M. Joachimski3, Yadong Sun3,4, Ivan Savov2, Stephen E. Grasby5,6, Benoit Beauchamp6, and Dierk P.G. Blomeier7 1Department of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences, University of Hull, Hull, HU6 7RX, United Kingdom 2School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, United Kingdom 3Geozentrum Nordbayen, Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Schlossgarten 5, 91054 Erlangen, Germany 4State Key Laboratory of Biogeology and Environmental Geology, China University of Geosciences, 388 Lumo Road, Wuhan, 470073, Hubei Province, P.R. China 5Geological Survey of Canada, 3303 33rd Street N.W., Calgary, Alberta, T2L 2A7, Canada 6Department of Geoscience, University of Calgary, 2500 University Drive N.W., Calgary Alberta, T2N 1N4, Canada 7Norwegian Polar Institute, Fram Centre, 9296 Tromsø, Norway ABSTRACT mass extinction events; it is regarded as either sil ranges in the Kapp Starostin Formation of one of the greatest of all Phanerozoic crises, Spitsbergen, a Permian-aged mixed spiculite The controversial Capitanian (Middle ranking alongside the “Big 5” (Stanley and chert-carbonate unit that formed in cool, shelf Permian, 262 Ma) extinction event is only Yang, 1994; Bond et al., 2010a), or, in a funda- seas of the Boreal Ocean (Ehrenberg et al., known from equatorial latitudes, and conse- mentally different appraisal, it is viewed not as 2001; Stemmerik and Worsley, 2005; Blomeier quently its global extent is poorly resolved. a mass extinction but as a protracted and gradu- et al., 2013; Dustira et al., 2013). -

Alphabetical List

LIST E - GEOLOGIC AGE (STRATIGRAPHIC) TERMS - ALPHABETICAL LIST Age Unit Broader Term Age Unit Broader Term Aalenian Middle Jurassic Brunhes Chron upper Quaternary Acadian Cambrian Bull Lake Glaciation upper Quaternary Acheulian Paleolithic Bunter Lower Triassic Adelaidean Proterozoic Burdigalian lower Miocene Aeronian Llandovery Calabrian lower Pleistocene Aftonian lower Pleistocene Callovian Middle Jurassic Akchagylian upper Pliocene Calymmian Mesoproterozoic Albian Lower Cretaceous Cambrian Paleozoic Aldanian Lower Cambrian Campanian Upper Cretaceous Alexandrian Lower Silurian Capitanian Guadalupian Algonkian Proterozoic Caradocian Upper Ordovician Allerod upper Weichselian Carboniferous Paleozoic Altonian lower Miocene Carixian Lower Jurassic Ancylus Lake lower Holocene Carnian Upper Triassic Anglian Quaternary Carpentarian Paleoproterozoic Anisian Middle Triassic Castlecliffian Pleistocene Aphebian Paleoproterozoic Cayugan Upper Silurian Aptian Lower Cretaceous Cenomanian Upper Cretaceous Aquitanian lower Miocene *Cenozoic Aragonian Miocene Central Polish Glaciation Pleistocene Archean Precambrian Chadronian upper Eocene Arenigian Lower Ordovician Chalcolithic Cenozoic Argovian Upper Jurassic Champlainian Middle Ordovician Arikareean Tertiary Changhsingian Lopingian Ariyalur Stage Upper Cretaceous Chattian upper Oligocene Artinskian Cisuralian Chazyan Middle Ordovician Asbian Lower Carboniferous Chesterian Upper Mississippian Ashgillian Upper Ordovician Cimmerian Pliocene Asselian Cisuralian Cincinnatian Upper Ordovician Astian upper