Brucerius Lecture 03. Juni 2012 an Der Universität Haifa Gehalten Von Prof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The PUA English Report 2011-2012

Editor: Nurit Felter-Eitan, Authority Secretary & Spokeswoman All information provided in this report is provided for information purposes only and does not constitute a legal act. The hebrew translation is the current and accurate information. Information in this report is subject to change without prior notice. Greetings, I am delighted to hereby present the Israel Public Utility Authority’s (Electricity) biennial activity report for the years 2012-2011. This report summarizes the Authority’s Assembly’s extensive and meticulous work, assisted by the Authority’s team of professional employees, over the past two years, signifying a turning point in the Israeli electricity and energy markets. Alongside a severe energy crisis that befell the electricity market in the past two years due to the discontinuation of natural gas supply from Egypt and the creation of a gas supply monopoly, these years have seen a historic change in the electricity market, commencing with the admission of private electricity entrepreneurship and clean electricity production in significant capacities (the Authority’s projection for private electricity production is 25% by 2016, and approximately 10% for electricity production using renewable energy by 2020). As a result of the natural gas crisis, which began in 2011 due to recurring explosions in the gas lines leading from Egypt to Israel, the Electricity Authority was faced with a reality that would have forced it to instantly and radically increase in the electricity tariffs for the Israeli consumers in 2012. These circumstances led the Authority to combine forces with government bodies, including the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Energy and Water Resources and the Ministry of Environmental Protection, and lead a comprehensive move which significantly restrained the tariff increase, and furthermore, relieved the electricity consumers’ burden in a manner that enabled spreading the tariff increase over three years. -

Aperegrinaciones 2012 A4.FH11

Delegación para España de la Custodia de Tierra Santa PP. FRANCISCANOS Peregrinaciones a Otros viajes: JORDANIA · ITALIA · MALTA Y SICILIA TURQUÍA · GRECIA · CROACIA · RUSIA · POLONIA · PRAGA 2012 NAZARET: Anunciación JERUSALÉN: Santo Sepulcro JERUSALÉN: Santo Sepulcro JERUSALÉN PETRA ASIS ROMA TIBERIADES: Bienaventuranzas PEREGRINATIO INTERPAX TERRAE SANCTAE Peregrinaciones interPAX ygy la Delegación para El viaje a Tierra Santa es una auténtica peregrinación a las raíces de nuestra fe cristiana de Tierra Santa - PP. Franciscanos y al encuentro de Jesús en su misma tierra. Es un viaje distinto a los demás: realizado por motivos religiosos e impregnado de sentido religioso. Para los cristianos suele ser el mejor viaje de su vida, como lo afirman al regreso de Experiencia Tierra Santa. InterPax, especialistas desde hace 40 años en Peregrinaciones a Tierra Santa. Pioneros y referente en España de auténticas peregrinaciones. El Centro Tierra Santa de de Madrid (Delegación Ponemos toda nuestra experiencia a su servicio para que realice su para España de la Custodia de Tierra Santa) en peregrinación o viaje con toda seguridad y sin sorpresas. colaboración con interPAX le ofrecen la posibilidad de realizar su peregrinación en Aviones Asistencia cualquier fecha del año, con una organización Para la mayoría de los vuelos, aeropuerto seria y con los precios más baratos del mercado. hemos elegido IBERIA, EL AL, Nuestro personal del aeropuerto de ALITALIA y otras compañías de línea Barajas se encarga de atenderle y La Asociación Peregrinaciones a regular de prestigio. ayudarle en los trámites de Tierra Santa con los Franciscanos facturación y embarque, a la vez Hotel de que está a su disposición para a Asociación Peregrinaciones a Tierra Santa facilitarle toda la información que conexión precise. -

Extensions of Remarks

658 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS ·January 14, 1969 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS THE CUBAN MISSil..E CRISIS four-part cable that Chairman Khrushchev broadcast from Moscow, and a U-2 was shot sent the afternoon of Friday, Oct. 26. This down over Cuba, killing the pilot, Major An cable marked the turning point in the Soviet derson. There seemed no alternative to bomb HON. FRANK CHURCH attitude and was the basis of the agreement ing the missiles sites, and following this with OF mAHO that resolved the crisis. Kennedy also docu an invasion. ments what had only been deduced before But it was Robert Kennedy who conceived IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES about the course events would probably have a brilliant diplomatic maneuver-later dub Tuesday, January 14, 1969 taken if the Soviets had not backed down bed the "Trollope ploy," after the recurrent the United States would have been forced to scene in Anthony Trollope's novels in which Mr. CHURCH. Mr. President, several take out the Soviet anti-aircraft SAM sites, the girl interprets a squeeze of her hand as a weeks ago, there appeared in the maga and, then, if the Soviets still persisted, to proposal of marriage. His suggestion was to zine Commonweal an article comment launch an invasion. deal with Friday's package of signals ing upon the book "13 Days," authored Many other details are also new, -but one Khrushchev's cable and the approach by our late colleague, Senator Robert F. is particularly significant-the account of through the Soviet intelligence agent-as Kennedy, concerning the 1962 Cuban Robert Kennedy's meeting with Ambassador if the reneging message of Saturday simply Dobrynin, the details of which supply a miss did not exist. -

The Six-Day War Itself

The Six-Day War Source: Israel Government Yearbook5728 (1967-68), Central Office of information, Prime Minister’s Office, March 1968, pp. 17-25 On the morning of Monday, 5 June 1967, Arab aggression led to the outbreak of air and ground fighting between Israel and Egypt. Within a few hours, attacks by Jordan, Syria and Iraq turned the fighting into war between Israel and the Arab States, Algeria, Kuwait and Sudan included, for they, too, dispatched combat units which took part in it. Instantly, Israel aircraft delivered a lightning assault upon the Egyptian air force and wiped it out in three short hours, and, on that same first day, the other enemy air forces were either wiped out, too, or badly mauled. Our armor, parachutists and infantry broke through in Sinai and the Gaza Strip overran the heavily-fortified lines of Egypt after bitter engagements and, thrusting hard and swiftly westward and southward, smashed seven Egyptian divisions and their nearly a thousand tanks. All Sinai was in our hands, the sea-lane to Eilat was open once more, and our troops stood on the eastern bank of the Suez Canal. On the Jordanian front, our forces drove into Judaea and Samaria in a multi-axial attack, worsted the Arab Legion, and in less than three days had taken the entire area. Jerusalem, one and undivided, was freed. On the Syrian front, we stormed the Golan Heights for all its powerful defenses, its difficult terrain and an enemy that offered stout resistance until, at length, it was broken. Egypt lost all its aircraft and most of its army, and its navy was not unscathed. -

The Renewing Kibbutz

The Renewed Kibbutz By Ronen Manor, Advocate1 Abstract Over the years, the unique form of cooperative settlement known as a kibbutz, has had to undergo various difficulties and changes, yet it has managed to maintain its principles and survive. Nevertheless, during the last decade, many kibbutzim have made substantial changes which contradict traditional kibbutz ideology. This article is based on the report of the Public Committee for the Kibbutzim. It describes the inevitable changes that have occurred and analyzes the reasons and considerations that have led to the creation of a new form of kibbutz. Introduction The economic crisis that overtook Israel in the mid 1980‟s had a dramatic effect on the traditional structure of the kibbutz. Many kibbutzim2 went through a severe financial crisis and were unable to repay their immense debts to the banking system. They had to commit themselves to long term debt settlements with the banks, and became increasingly dependent on their creditors. The crisis weakened both the authority and status of the Kibbutz movement, and caused a significant deterioration in its demographic and social structure, since much of the young generation had left the Kibbutz, while new members were reluctant to join. Furthermore, kibbutzim that went bankrupt were no longer able to supply the basic needs of their members, especially of the older generation whose economic welfare has become insecure. Many kibbutzim felt, therefore, that fundamental changes had to be made and, in effect, various changes in all aspects of life have been gradually implemented in the majority of kibbutzim. The first change refers to economic management. -

THE MIDDLE Eash NATIONAL SECURITY FILES, 1961-1963

THE JOHN F. KENNEDY NATIONAL SECURITY FILES THE MIDDLE EASh NATIONAL SECURITY FILES, 1961-1963 UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of The John F. Kennedy National Security Files General Editor George C. Herring THE MIDDLE EAST National Security Files, 1961-1963 Microfilmed from the holdings of The John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts Project Coordinator Robert E. Lester Guide compiled by Blair Hydrick A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The John F. Kennedy national security files. The Middle East [microform]: national security files, 1961-1963. microfilm reels "Microfilmed from the holdings of the John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts; project coordinator, Robert E. Lester." Accompanied by printed reel guide compiled by Blair D. Hydrick. ISBN 1-55655-013-8 (microfilm) ISBN 1-55655-014-6 (printed guide) 1. Middle East-Politics and government-1945-1979-Sources. 2. Middle East-Foreign relations-United States-Sources. 3. United States-Foreign relations-Middle East-Sources. I. Lester, Robert. II. Hydrick, Blair. III. John F. Kennedy Library. IV. University Publications of America (Firm) [DS63.1.J65 1991] 327.73056-dc20 91-14019 CIP Copyright © 1987 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-014-6. TABLE OF CONTENTS General Introduction—The John F. Kennedy National Security Files: "Country Files," 1961-1963 v Introduction—The John F. Kennedy National Security Files: Middle East, 1961-1963 ix Scope and Content Note xiii Source Note xv Editorial Note xv Security Classifications xvii Key to Names xix Initialism List xxv Reel Index Reel 1 Afghanistan 1 Cyprus 12 India 17 Reel 2 India conl 24 Iran 29 Israel 49 Reels Israel cont 50 Saudi Arabia 73 United Arab Republic 79 Yemen 85 Author Index 87 Subject Index 91 GENERAL INTRODUCTION The John F. -

![The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited [2Nd Edition]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9550/the-birth-of-the-palestinian-refugee-problem-revisited-2nd-edition-6959550.webp)

The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited [2Nd Edition]

THE BIRTH OF THE PALESTINIAN REFUGEE PROBLEM REVISITED Benny Morris’ The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949, was first published in 1988. Its startling reve- lations about how and why 700,000 Palestinians left their homes and became refugees during the Arab–Israeli war in 1948 undermined the conflicting Zionist and Arab interpreta- tions; the former suggesting that the Palestinians had left voluntarily, and the latter that this was a planned expulsion. The book subsequently became a classic in the field of Middle East history. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited represents a thoroughly revised edition of the earlier work, compiled on the basis of newly opened Israeli military archives and intelligence documentation. While the focus of the book remains the 1948 war and the analysis of the Palestinian exodus, the new material con- tains more information about what actually happened in Jerusalem, Jaffa and Haifa, and how events there eventually led to the collapse of Palestinian urban society. It also sheds light on the battles, expulsions and atrocities that resulted in the disintegration of the rural communities. The story is a harrowing one. The refugees now number some four million and their existence remains one of the major obstacles to peace in the Middle East. Benny Morris is Professor of History in the Middle East Studies Department, Ben-Gurion University.He is an outspo- ken commentator on the Arab–Israeli conflict, and is one of Israel’s premier revisionist historians. His publications include Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist–Arab Conflict, 1881–2001 (2001), and Israel’s Border Wars, 1949–56 (1997). -

Middle. E,Ast Record

MIDDLE. E,AST RECORD VOLUME ONE 1960 THE ISRAEL ORIENTAL SOCIETY THE REUVEN SHILOAH RESEARCH CENTER Tel Aviv, P.O.B. 1067 5 ,l]]tltlllr{fl ARAB.ISRADL BORDEI{ RELATIONS THE ISRADLI.SYRTAN BORDER lJpper Talvafiq at a traclcl --- -. Katzir area, and later in:.-: -- - [Incidents in the southern DZ started in Dec 1959, and inc:-::: occurred daily from 26 The viilage officer investigating the armed clashes Jan. Syrian Army sirokesman :-.- Tarvafiq rvas raided by Israel Defence Forces (IDF) A * of -Feb plating aggressive action in :: I 1 and clashes continued until 6 Feb. Later = units on rrould be rcpelled by for,e. .. the month lvarlike tension ensued betrveen Israel ar-rd - in 14 the UAR, (On these see p 197 ff.) The incidents in the June) On 14' fi.re rtas o1 -- northern DZ in Feb described belorv were regarded at thc June =:.i; the Bnot Ya'akov bridge. .:', : time as a consequence of the tension.] -- On 15 June Syrian positic:-i ::-- a tractor ploughing a field ne;.: l.- Jan-June: Various Incidents. During the soqin.q- season, (collective village) of Dan in the Huleh Val- lune ) ih" kibbrrt, Cairo Radio :r'- :::r. also cultivated its land in the northern DZ. In the On 27 June ley Akhbar a statement by the f ::r: course of this r,r'ork, Israeli tractors struck mines in the man to the cffcct tllat the >. --::' area nine times. (Ila'aretz' 14 Jan) borders by gangs" r'c'-:-: : patrol r'vas fired on north-east of Kfar Szold. "Israeli An Israeli the :r: .-...: (Ha'aretz, torious UAR Armies in i::-.: i: 14 Jan) Islacli artillcry fire one sin-ele..'.' On 26 an Israeli soidier was slightly t''ounded u'hen Jan the Israeli border area into a 1i"':: a squad ol Syrian troops penetrated about 150 metres into follow the aggression a min'::: Israel territory and fiied at a patrol, north-east of Kfar in the establishment of contact oL :': : : :: : '. -

Coping with Fear: Frontier Kibbutzes and the Syrian-Israeli Border War

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 21 (2019) Issue 2 Article 5 Coping with Fear: Frontier Kibbutzes and the Syrian-Israeli Border War Orit Rozin Tel Aviv University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Rozin, Orit. -

(EN) שרות ימי עסקים אבו ג'ווייעד )שבט( קבלן קבלן שוג ובא Abu Ghosh +2 תו

ימי עסקים שרות (City (HE) City (EN קבלן קבלן אבו ג'ווייעד )שבט( 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Abu Ghosh אבו גוש 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Abu Sinan אבו סנאן קבלן קבלן Abu Sarihan אבו סריחאן )שבט( קבלן קבלן Abu Abdun אבו עבדון )שבט( קבלן קבלן Abu Ammar אבו עמאר )שבט( קבלן קבלן אבו עמרה )שבט( קבלן קבלן אבו קורינאת )שבט( קבלן קבלן אבו קרינאת )יישוב( קבלן קבלן אבו רובייעה )שבט( קבלן קבלן Abu Ruqayq אבו רוקייק )שבט( קבלן קבלן אבו תלול 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Ibtin אבטין קבלן קבלן Avtalion אבטליון קבלן קבלן Aviel אביאל קבלן קבלן Avivim אביבים 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Avigdor אביגדור Avihayil אביחיל 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Avital אביטל 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Aviezer אביעזר 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Abirim אבירים קבלן קבלן Even Haayin אבן העזר Even Yehuda אבן יהודה 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Even Menachem אבן מנחם 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Even Sapir אבן ספיר 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Even Shmuel אבן שמואל 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Avnei Eitan אבני איתן קבלן קבלן Avnei Hefetz אבני חפץ קבלן קבלן Avnat אבנת קבלן קבלן Absalom אבשלום קבלן קבלן Adora אדורה קבלן קבלן Adirim אדירים 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Adamit אדמית 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Aderet אדרת Aodim אודים קבלן קבלן Odem אודם קבלן קבלן Ohad אוהד 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Ohalo אוהלו קבלן קבלן אולפני ג.ג קבלן קבלן Umm al-Fahm אום אל-פחם קבלן קבלן Umm al-Qutuf אום אל-קוטוף 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Umm Batin אום בטין קבלן קבלן Omen אומן 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Omets אומץ 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Ofakim אופקים 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Or HaGanuz אור הגנוז 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Or HaNer אור הנר Or Yehuda אור יהודה Or Akiva אור עקיבא 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Ora אורה 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Orot אורות 2+ תוספת ימי עסקים Ortal -

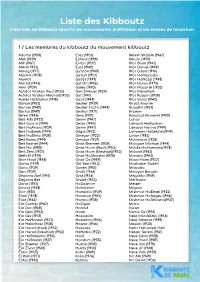

Liste Des Kibboutz Cette Liste De Kibboutz Spécifie Les Mouvements D’Affiliation Et Les Années De Fondation

Liste des Kibboutz Cette liste de kibboutz spécifie les mouvements d’affiliation et les années de fondation. 1 / Les membres du kibboutz du mouvement kibboutz Adamit (1958) Erez (1950) Kerem Shalom (1967) Afek (1939) Eshbal (1998) Ketura (1970) Afik (1967) Evron (1937) Kfar Blum (1943) Afikim 1932) Eyal (1949) Kfar Daniel (1949) Almog (1977) Ga’aton (1948) Kfar Giladi (1916) Allonim (1938) Ga’ash (1951) Kfar HaMaccabi Alumot Gadot (1949) Kfar HaNassi (1948) Ami’ad (1946) Gal On (1946) Kfar Haruv (1973) Amir (1939) Galed (1945) Kfar Masaryk (1933) Ashdot Ya’akov Ihud (1933) Gan Shmuel (1920) Kfar Menahem Ashdot Ya’akov Meuhad(1933) Gat (1941) Kfar Ruppin (1938) Ayelet HaShahar (1918) Gazit (1948) Kfar Szold (1942) Bahan (1953) Gesher (1939) Kiryat Anavim Bar’am (1949) Gesher HaZiv (1949) Kissufim (1951) Barkai (1949) Geshur (1971) Kramim Be’eri (1946) Geva (1921) Kvoutzat Kinneret (1909) Beit Alfa (1922) Gevim (1947) Lahav Beit Guvrin (1949) Gezer (1945) Lehavot HaBashan Beit HaArava (1939) Gevim (1947) Lehavot Haviva (1949) Beit HaEmek (1949) Gilgal (1972) Lohamey HaGeta’ot(1949) Beit HaShita (1928) Ginegar (1922) Lotan (1983) Beit Kama (1949) Ginosar (1937) Ma’abarot (1925) Beit Keshet (1944) Givat Brenner (1928) Ma’agan Michael (1949) Beit Nir (1955) Givat Haim (Ihud) (1953) Ma’ale HaHamisha(1938) Beit Zera (1921) Givat Haim (Meuhad)(1953) Ma’anit (1942) Beth-El (1970) Givat HaShlosha (1925) Manara (1943) Bror Hayil (1948) Givat Oz (1949) Maoz Haim (1937) Dafna (1939) Glil Yam (1943) Mashabei Sadeh Dalia (1939) Gonen (1951) Matzuba -

A Case Study Was Made of Comprehensive Efforts to Get Young

VIIMPINT IIM/11/MM ED 030 581 24 SP 002 088 By-Eaton, Joseph W.; Chen, Michael Influencing The Youth Culture; A Study Of Youth Organizations In Israel. Final Report. Piitsburgh Univ., Pa. Graduate School of Social Work.; Szold Inst. of BehavioralSciences, Jerusalem (Israel). Spons Agency-Office of Edycation (DHEW), Washington, D.C. Bureau of Research. Bureau No -BR -5 -0375 Pub Date 1 Feb. 69 Contract -OEC -4 -10 -010 Note-396p. Available from-Sage Publications, Inc., 275 South Beverly Drive, Beverly Hills, California 90212 EDRS Price MF -$1.50 HC Not Available from EDRS. Descriptors -*Acculturation,Attitudes,DevelopingNations, DisadvantagedYouth,History,Immigrants, Individual Development, Leadership, Nationalism, *National Organizations, *National Surveys, Pacticipant Involvement, Political Influences, Program Planning, Recruitment, Social Influences, Socialization, Social Status, Values, *Youth, Youth Leaders, Youth Opportunities, *Youth Programs Identifiers -Gadna Youth.Corps, Israel A case study was made of comprehensive efforts to getyoung people to identify with the core ideals of the parental .generation through youth organizations in Israel. where over 90% of the adolescents reportan ,active involvement in One or more of three nationwide programs youth movements, sponsored by political parties and the Scouts. the "Cadna" youthcorps, sponsored jointly by the schools and the Ministry of Defense--a sort of high school R.O.T.C. with premilitaryas well as national serv(ce goals1 and beyond-school. programs providing group work, skill training, education, and recreational services in community centers and in school buildings after hours. Large samples of youths and youth leaders were interviewed. Among the variables studies were recruitment, programming. resignation. leadership. and attitudes toward national service.