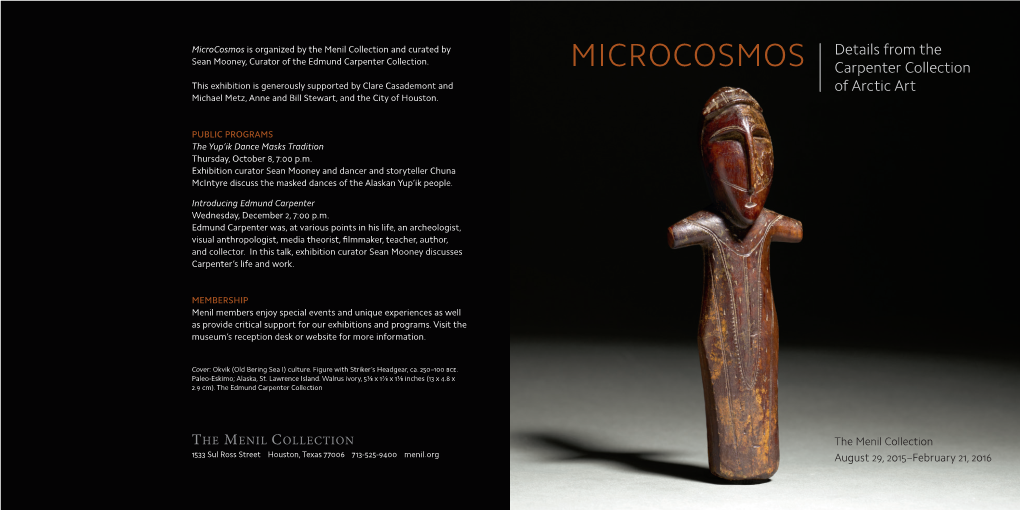

MICROCOSMOS Details from the Carpenter Collection of Arctic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upside Down: Arctic Realities

Upside Down: Arctic Realities http://www.caareviews.org/reviews/1746 critical reviews of books, exhibitions, and projects in all areas and periods of art history and visual studies published by the College Art Association Donate to caa.reviews January 4, 2012 Edmund Carpenter, ed. Upside Down: Arctic Realities Exh. cat. Houston: Menil Collection, 2011. 232 pp.; 132 color ills.; 62 b/w ills. Cloth $50.00 (9780300169386) Exhibition schedule: Musée du quai Branly, Paris, September 30, 2008–January 11, 2009; Menil Collection, Houston, April 15—July 17, 2011 Marcia Brennan CrossRef DOI: 10.3202/caa.reviews.2012.2 Yup’ik, Southwest Alaska. “Tomanik” (wind-maker) mask or Summer/Winter mask (late 19th century). Wood, feathers, pigment, fiber. 37 x 16 x 10 in. (94 x 40.6 x 25.4 cm). © Rock Foundation, New York. Photo: Fred Gageneau. When describing the carved artworks of the Aboriginal people of the Arctic regions, the anthropologist Edmund Snow Carpenter once observed: “A distinctive mark of the traditional art is that many of the ivory carvings, generally of sea mammals, won’t stand up, but roll clumsily about. Each lacks a single, favored point of view, hence, a base. Indeed, they aren’t intended to be set in place and viewed, but rather to be worn or handled, turned this way and that. The carver himself explains his effort as a token of thanks for food or services received from the animal’s spirit” (16). Much like the individual artworks displayed in Upside Down: Arctic Realities, the exhibition itself could be seen as a composite phenomenon that is best approached from multiple perspectives at once and “turned this way and that.” In its creative conflations and inversions of Paleolithic and modern motifs, the show simultaneously cultivated the perspectives of ethnographic anthropology and contemporary art criticism, with their attendant conceptions of distanced criticality and aesthetic proximity. -

By Popular Geek Publication Wired Because of His Viral Youtube Video

University of Manitoba, Information Services and Technology, Michael Wesch and the Future of Education, June 17, 2008 Dubbed “the explainer” by popular geek publication Wired because of his viral YouTube video that summarizes Web 2.0 in under five minutes, cultural anthropologist Michael Wesch brought his Web 2.0 wisdom to the University of Manitoba on June 17. During his presentation, the Kansas State University professor breaks down his attempts to integrate Facebook, Netvibes, Diigo, Google Apps, Jott, Twitter, and other emerging technologies to create an education portal of the future. “It’s basically an ongoing experiment to create a portal for me and my students to work online,” he explains. “We tried every social media application you can think of. Some worked, some didn’t.” 1 From umanitoba.ca/ist/production/streaming/podcast_wesch.html 13 July 2008 Michael Wesch Assistant Professor of Cultural Anthropology SASW, 206 Waters Hall Kansas State University Manhattan, KS 66506 Phone: 785-532-6866 Fax: 785-532-6978 Email: [email protected] Michael Wesch is a cultural anthropologist and media ecologist exploring the impacts of new media on human interaction. He graduated summa cum laude from the Kansas State University Anthropology Program in 1997 and returned as a faculty member in 2004 after receiving his PhD in Anthropology at the University of Virginia. There he pursued research on social and cultural change in Melanesia, focusing on the introduction of print and print-based practices like mapping and census-taking in the Mountain Ok region of Papua New Guinea where he lived for a total of 18 months from 1999-2003. -

Paleo-Eskimo Artifacts from the Edmund Carpenter Collection Populate a Universe of Their Own in Microcosmos: Details from the Carpenter Collection

Paleo-Eskimo Artifacts from the Edmund Carpenter Collection Populate a Universe of Their Own In MicroCosmos: Details from the Carpenter Collection On view exclusively at the Menil, August 29, 2015 through February 21, 2016 HOUSTON, TEXAS, August 20, 2015 — Over the course of the second half of the twentieth century, Edmund Carpenter—anthropologist, author, broadcaster, filmmaker, and communications theorist—assembled one of the world’s finest and most extensive collections of artifacts made and used by the peoples of the Old Bering Sea cultures of coastal Alaska and Siberia. Dating from as early as 250 BCE and carved from walrus ivory (or wood, as seen in rare examples that have survived), these dolls, ornaments, game pieces, tools, and ceremonial objects are diminutive in scale. Mere inches in height, they speak powerfully of cultural forces that led to their creation—specifically, a belief in the fluid and fantastic transformation from human to animal and back again. In MicroCosmos seals and water fowl sprout human heads, pregnant women grow walrus tusks, shamans fly like birds, and mythical beasts shift into multiple shapes. The exhibition’s opening on August 29, 2015 marks the first public display of the Carpenter Collection of Arctic Art (a trove of some 150 Paleo-Eskimo objects). Alone among archaeologists and anthropologists when he delved into the Arctic and its peoples, Edmund Carpenter conducted groundbreaking research that led to the publication of “Eskimo Realities,” (1959/1973), one of many landmarks in a career that spanned the globe. Edmund Carpenter died in 2011 at the age of 88. Inviting museum visitors into another world, MicroCosmos: Details from the Carpenter Collection has been organized by its curator, Sean Mooney. -

Focality and Extension in Kinship Essays in Memory of Harold W

FOCALITY AND EXTENSION IN KINSHIP ESSAYS IN MEMORY OF HAROLD W. SCHEFFLER FOCALITY AND EXTENSION IN KINSHIP ESSAYS IN MEMORY OF HAROLD W. SCHEFFLER EDITED BY WARREN SHAPIRO Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN(s): 9781760461812 (print) 9781760461829 (eBook) This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph of Hal Scheffler by Ray Kelly. This edition © 2018 ANU Press To the memory of Harold Walter Scheffler, a compassionate man of the highest scholarly standards Contents List of Figures and Tables . ix Acknowledgements . xiii Contributors . xv Part I. Introduction: Hal Scheffler’s Extensionism in Historical Perspective and its Relevance to Current Controversies . 3 Warren Shapiro and Dwight Read Part II. The Battle Joined 1 . Hal Scheffler Versus David Schneider and His Admirers, in the Light of What We Now Know About Trobriand Kinship . 31 Warren Shapiro 2 . Extension Problem: Resolution Through an Unexpected Source . 59 Dwight Read Part III. Ethnographic Explorations of Extensionist Theory 3 . Action, Metaphor and Extensions in Kinship . 119 Andrew Strathern and Pamela J. Stewart 4 . Should I Stay or Should I Go? Hunter-Gatherer Networking Through Bilateral Kin . 133 Russell D. Greaves and Karen L. -

Cross-Cultural Explorations with Camera and Analytic Text in Cusco, Peru

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2014 Old World, New Media: Cross-cultural Explorations with Camera and Analytic Text in Cusco, Peru Scott DuPre Mills Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/3454 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT PAGE Scott DuPre Mills 2014 All Rights Reserved 1 Old World, New Media: Cross-cultural Explorations with Camera and Analytic Text in Cusco, Peru A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Media, Art and Text at Virginia Commonwealth University. by Scott DuPre Mills BFA Sculpture, Virginia Commonwealth University 1989. MFA Photography and Film, Virginia Commonwealth University 1999. Director: Dr. Nicholas A Sharp Assistant Professor Department of English Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia January, 2014 Acknowledgement My committee members have contributed ideas and opinions that have been essential to the development of this project. Dr. Peter Kirkpatrick told me of the new MATX Phd. Program in 2005. I applied and was offered a full GTA in its first year and began in the fall of 2006. Peter’s suggestion of Deluze’s theoretical writings was essential to the camera consciousness component of this dissertation. -

Introduction 2013

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Liv Hausken Introduction 2013 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/13192 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Hausken, Liv: Introduction. In: Liv Hausken (Hg.): Thinking Media Aesthetics. Media Studies, Film Studies and the Arts. Berlin: Peter Lang 2013, S. 29–50. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/13192. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Introduction Liv Hausken All through the 20th century, there have been rich and complex interchanges between aesthetic practices and media technologies. Along with the arrival of mass media, new technological forms of culture were gradually added to the old typologies of the arts. Photography, film, television, and video increasingly ap- peared in the curricula of art schools and were given separate departments in art museums. With the introduction of digital media technologies in the 1980s and 1990s, the means of production, storage, and distribution of mass media changed, and eventually, so did its uses. As artists adopted the technologies of mass media, the economy of fine art (like the economy of limited editions) was confronted with the logics of mass production and mass distribution. Thus, when visiting a contemporary art museum one might find, for example, such conceptually con- tradictory displays as “DVD, edition of 3” (see for instance Lev Manovich 2000). -

PREHISTORIC OR PRE-EUROPEAN ARCHAEOLOGY in MAINE BIBLIOGRAPHY of PUBLISHED ARTICLES Through Summer 2018

PREHISTORIC OR PRE-EUROPEAN ARCHAEOLOGY IN MAINE BIBLIOGRAPHY OF PUBLISHED ARTICLES through summer 2018 compiled by Arthur Spiess Maine Historic Preservation Commission This bibliography is current through the summer of 2018. Our purpose is to record publications that include Maine archaeological site information, either focusing on Maine, one or more Maine sites, or that mention Maine archaeological information in a comparative context. Allison, Roland 1951 Digging and searching the shell heaps of Maine, Algonquin Culture, Eggemoggin Reach, Hancock County, Maine. Ohio Archaeologist 1(1):16 1952 A days dig in a Maine shell heap. Ohio Archaeologist 2(2):7-8 1953 Shell heap digging in Maine. Ohio Archaeologist 3(4):27-29 1972 More about the shell heaps. The Maine Archaeological Society Bulletin 12(2):1-3. Anderson, Walter A. and J. Kelly, thers 1984 Crustal Warping in Coastal Maine. Geology 12:677-680 Anonymous 1912 Investigations of Maine shell-heaps. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 59(11): 46-48 Anonymous 1976 Introduction to Artifact Photographs. The Maine Archaeological Society Bulletin 16(2):32-42 Ashley, Asch Sidell, Nancy 1999 Prehistoric Plant Use in Maine: Paleoindian to Contact Period. Pp. 191-223 in Current Northeast Paleoethnobotany, edited by John P. Hart. New York State Museum Bulletin:494. 2002 Paleoethnobotanical Indicators of Subsistence and Settlement Change in the Northeast. John Hart and Christina Rieth, editors. Northeast Subsistence - Settlement Change A.D.700-1300, NY State Museum Bulletin 496:241-263. 2008 The Impact of Maize-based Agriculture on Prehistoric Plant Communities in the Northeast. Pp. 29-52 in Current Northeast Paleoethnobotany II, edited by John P. -

Creeping Plants and Winding Belts: Cognition, Kinship, and Metaphor Bojka Milicic

10 Creeping Plants and Winding Belts: Cognition, Kinship, and Metaphor Bojka Milicic Introduction Hal Scheffler’s work has been fundamental in illuminating studies of human kinship and his perspective on kin terms lends itself to a cognitive approach. There is a growing body of research (e.g. Leaf and Read 2012) showing that the study of kinship has a great potential for gaining insight into cognitive processes. Thus studying metaphors that describe concepts from the domain of kinship are salient for the study of human cognition. Advocates of culturalist or performative persuasion argue that native theories about biological procreation are purely culturally constructed and are only metaphors of social relations, while sociobiologists and evolutionary ecologists would have it the other way around: for the former, Darwinian fitness is just a metaphor of immortality; for the latter, immortality is just a metaphor of Darwinian fitness. Thus Marshall Sahlins, a culturalist, argues: ‘Whereas it is commonly supposed that classificatory kin relations represent “metaphorical extensions” of the “primary” relations of birth, if anything it is the other way around: birth is the metaphor’ (2012: 677). What lies at the heart of both positions are 327 FOCALITy AND ExTENSION IN KINSHIP metaphors. Metaphorical thought plays an important role in the concepts of kinship. As Sahlins notes, kinship is often perceived through shared substances of blood, milk, semen, flesh, bone, spirit (2011a, 2011b). A metaphorical expression provides a relation between a source concept and its target concept, which is essentially based on analogy (Pinker 2007: 253–55). Metaphors are extensions from one semantic domain to another. -

Tribal Heritage and Tribal Indology

M.A in Tribal Heritage and Tribal Indology KALINGA INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Deemed to be University under section 3 of UGC act 1956 Department/Course Tribal Heritage and Tribal Indology (THTI) Course Details 1 M.A in Tribal Heritage and Tribal Indology Department of Tribal Heritage and Tribal Indology (THTI) Introduction: Heritage is a fundamental source of individual and group identity, vitality, and solidarity. Heritage is a universal process by which humans maintain connections with our pasts, assert our similarities with and differences from one another, and tell our children and other young people what we think is important and deserves to be part of the future. Traditional languages were disappearing, and ancestral forms of conflict resolution within communities were disintegrating. Also, during this time, the federal government became aware of the difficulty tribal communities were having in retaining cohesion. Tribal governments as well as the federal government began investigating ways to halt degradation of traditional cultures. India has been a subject of intense interest to a wide variety of peoples from all corners of the ancient and the modern world throughout the millennia. There are many reasons for this intense and sustained interest, not least among them being the considerable prowess of the ancient Indic in matters of scholarship, relating to the exact sciences. The Indian university system of the ancient era was world renowned and attracted student from a wide variety of countries. Tribal Indology is to the academic study of the history, languages, and cultures of the tribal in Indian subcontinent. Strictly speaking it encompasses the study of the languages, scripts of all of Asia that was influenced by Indic culture. -

Thinking Media Aesthetics

Thinking Media Aesthetics Liv Hausken (ed.) Thinking Media Aesthetics Media Studies, Film Studies and the Arts Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. The publication of this book was supported by The Research Council of Norway. Cover illustration: I´m Not There, Todd Haynes, 2007. Screenshot from trailer. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Thinking media aesthetics : media studies, film studies and the arts / Liv Hausken, ed. pages cm ISBN 978-3-631-64297-9 1. Mass media—Aesthetics. 2. Motion pictures—Aesthetics. 3. Aesthetics. 4. Art—Philosophy. I. Hausken, Liv, 1965- editor of compilation. P93.4.T48 2013 302.23—dc23 2013016063 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org ISBN 978-3-631-64297-9 (Print) E-ISBN 978-3-653-03162-1 (E-Book) DOI 10.3726/978-3-653-03162-1 Open Access: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 unported license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ © Liv Hausken, 2013 Peter Lang GmbH Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften Berlin www.peterlang.com Contents List of Contributors ............................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgements Liv Hausken ....................................................................................................... -

Tesi Definitiva

ALMA MATER STUDIORUM UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI BOLOGNA DIPARTIMENTO DI S CIENZE E CONOMICHE Dottorato di ricerca in Qualità Ambientale e Sviluppo Economico Regionale (Ciclo XVIII) Settore disciplinare di afferenza: Geografia MGGR/01 Esame finale anno 2007 Matr. 5914 PAESAGGI DI NOTE : BOLOGNA C ITTÀ DELLA M USICA Stefania Bettinelli Coordinatore: Chiar.mo Prof. Carlo Cencini Relatore: Chiar.mo Prof. Flavio Lucchesi Correlatore: Chiar.mo Prof. Francesco Vallerani 1 2 A mia madre, che si sta preparando piano al suo ultimo viaggio. E a mio figlio, a mio padre, a Francesca, a Gianfranco, a Raffaella, a Francesco e a tutti gli amici che mi hanno accompagnata in questa impresa 3 4 INDICE INTRODUZIONE 7 1. L'APPROCCIO CULTURALE E GEOUMANISTICO 11 1.1 Il punto di partenza: il paesaggio 11 1.2 L'approccio iconografico al paesaggio 15 1.3 La geografia umanistica 21 1.4 Applicazioni e prospettive dell'analisi geoletteraria 26 Bibliografia 36 2. GEOGRAFIA E MUSICA 47 2.1 Premessa 47 2.2 Un approccio necessariamente interdisciplinare 47 2.3 Il pasaggio sonoro 51 2.4 Lo spazio acustico 57 2.5 L’inquinamento acustico 60 2.6 I suoni della natura 62 2.7 Il paesaggio acustico 63 Appendice 1: Il paesaggio acustico dell’Asia evocato da Francesco Guccini 66 Appendice 2: Il paesaggio acustico dell’Abetone di Beatrice di Pian degli Ontani e di Francesca Alexander 69 Bibliografia 81 3. BOLOGNA CITTÀ CREATIVA 89 3.1 Il milieu urbano come nodo locale delle reti globali 89 3.2 Bologna “città digitale”: un esempio di best practice di democrazia telematica 93 3.3 Cultura, innovazione e creatività 95 5 3.4 Il Network delle Città Creative 97 Bibliografia 105 4. -

Anthropology 380-01 Dr. Judkins Spring 2019

Anthropology 380-01 Dr. Judkins Spring 2019 Experimental Course: ANTHROPOLOGY AT THE MARGINS The purpose of this course is deeper knowledge and appreciation of the science and art of Anthropology, to help students understand more thoroughly the full power of the paradigm of the field. The method used to accomplish this purpose is the exploration of the works of (1) people who were, themselves, marginal to formal Anthropology, yet highly (if uniquely) successful in the practice of the field, and/or (2) the study of marginal groups, groups on the very edges of classification, or sometimes between “stages” in their settings, e.g., caught between their own existence in a classical vs. in a modern state. The outcome will be to show how effective Anthropology can be even in the least likely of circumstances, or even when practiced by an Anthropologist as “marginal” as the “natives” themselves. Anthropology will be able to be seen as a paradigm of immense power in the hands of gifted students of the field. They will take from the course a deeper appreciation of what they can appreciate and of what they themselves can do with Anthropology. ALPHABETICAL & BIOGRAPHICAL ANTHROPOLOGIST/SUBJECT OUTLINE FOR COURSE 1 Roy Franklin Barton, DDS, Autobiographies of Three Pagans in the Philippines (1938); also author of Ifugao Law, pioneering work in Legal Anthropology and case studies - [dental surgeon] 2 Robert Bringhurst - Canadian, MFA, PhD x2 (Honorary), A Story as Sharp as a Knife (1999) (volume I of his trilogy: Masterworks of the Classical Haida Mythtellers) – [POLYMATH: polyglot linguist (Ancient Greek, Arabic, Navajo, Haida among others), translator, poet, writer, ethno-poet, anthropologist, book designer and master typographer] 3 Sir Peter H.