SPRING 2012 Number 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Transnational Politics of Aceh and East Timor in the Diaspora

MAKING NOISE: THE TRANSNATIONAL POLITICS OF ACEH AND EAST TIMOR IN THE DIASPORA by KARLA S. FALLON A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Political Science) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) May 2009 © Karla S. Fallon, 2009 Abstract This dissertation analyzes the transnational politics of two new or incipient diasporas, the Acehnese and East Tirnorese. It examines their political roles and activities in and across several countries in the West (Europe, North America, and Australia) as well as their impact on the “homeland” or country of origin, during and after armed conflict. It suggests that the importance of diaspora participation in conflict and conflict settlement is not solely or even primarily dependent on the material resources of the diaspora. Instead it is the ideational and political resources that may determine a diaspora’s ability to ensure its impact on the homeland, on the conflict, and its participation in the conflict settlement process. This study adopts a constructivist approach, process-tracing methods, and an analytical framework that combines insights from diaspora politics and theories on transnational advocacy networks (TANs). It concludes that the Aceh and East Timor cases support the proposition that diasporas are important and dynamic political actors, even when they are small, new, and weak. These cases also support the proposition that the political identities and goals of diasporas can be transformed over time as a diaspora is replenished with new members who have new or different ideas, as factions within diasporas gain power vis-à-vis others, and/or as the political partners available to the diaspora in the hostland and internationally change or broaden. -

A Nation Is Born, Again by Curt Gabrielson

CG-18 Southeast Asia Curt Gabrielson, a science teacher and an Institute Fellow, is observing the re- ICWA establishment of education in East Timor. LETTERS A Nation Is Born, Again By Curt Gabrielson JUNE 1, 2002 Since 1925 the Institute of Current World Affairs (the Crane- BAUCAU, East Timor–My most recent look at the political situation in East Timor Rogers Foundation) has provided (CG-11, November 2001) had a Constituent Assembly elected with the goal of long-term fellowships to enable drafting the nation’s new constitution. The Assembly was composed of 88 mem- bers: 75 national representatives, and one each from the 13 districts. This group of outstanding young professionals 24 women and 64 men viewed various constitutional models from around the to live outside the United States world, and each major party put forth a draft constitution to be considered. and write about international areas and issues. An exempt I found the whole process a bit overwhelming. The “Mother Law,” as it is operating foundation endowed by called in Tetum, East Timor’s lingua franca, is all-important; this much I had the late Charles R. Crane, the learned in high-school. How to write one from scratch, however, was not covered Institute is also supported by in Mr. Krokstrom’s civics class. contributions from like-minded individuals and foundations. The Assembly’s constitutional debates were broadcast on national radio, and one could follow them by drifting in and out of small shops and walking by houses with open windows. What I heard was sometimes incoherent, not necessarily TRUSTEES logical, often unorganized, but always very passionate. -

Divided Loyalties

DIVIDED LOYALTIES: Displacement, Belonging and Citizenship among East Timorese in West Timor Andrey Yushard Damaledo A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University January 2016 I declare that this thesis is my own work and that I have acknowledged all results and quotations from the published or unpublished work of other people. Andrey Yushard Damaledo Department of Anthropology School of Culture, History and Language College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University Page | ii This thesis is dedicated to my parents Page | iii ABSTRACT This thesis is an ethnographic study of belonging and citizenship among former pro-autonomy East Timorese settlers who have elected to settle indefinitely in West Timor. In particularly I shed light on the ways East Timorese construct and negotiate their socio-political identities following the violent and destructive separation from their homeland. In doing so, I examine the ways different East Timorese groups organise and represent their economic, political and cultural interests and their efforts to maintain traditional exchange relationships in the production and reproduction of localities, inscribing connection and informing entitlement in Indonesian Timor. East Timorese in West Timor have been variously perceived as ‘refugees’ (pengungsi), ‘ex-refugees’ (eks pengungsi), and/or ‘new citizens’ (warga baru). I argue, however, that these labels misunderstand East Timorese socio-political identities in contemporary Indonesia. The East Timorese might have had Indonesia as their destination when they left the eastern half of the island in the aftermath of the referendum, but they have not relinquished their cultural identities as East Timorese. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Chapter 1 1 Country Overview 1 Country Overview 2 Key Data 4 Burma (Myanmar) 5 Asia 6 Chapter 2 8 Political Overview 8 History 9 Political Conditions 12 Political Risk Index 57 Political Stability 71 Freedom Rankings 87 Human Rights 98 Government Functions 102 Government Structure 104 Principal Government Officials 115 Leader Biography 125 Leader Biography 125 Foreign Relations 128 National Security 140 Defense Forces 142 Chapter 3 145 Economic Overview 145 Economic Overview 146 Nominal GDP and Components 149 Population and GDP Per Capita 151 Real GDP and Inflation 152 Government Spending and Taxation 153 Money Supply, Interest Rates and Unemployment 154 Foreign Trade and the Exchange Rate 155 Data in US Dollars 156 Energy Consumption and Production Standard Units 157 Energy Consumption and Production QUADS 159 World Energy Price Summary 160 CO2 Emissions 161 Agriculture Consumption and Production 162 World Agriculture Pricing Summary 164 Metals Consumption and Production 165 World Metals Pricing Summary 167 Economic Performance Index 168 Chapter 4 180 Investment Overview 180 Foreign Investment Climate 181 Foreign Investment Index 184 Corruption Perceptions Index 197 Competitiveness Ranking 208 Taxation 217 Stock Market 218 Partner Links 218 Chapter 5 220 Social Overview 220 People 221 Human Development Index 222 Life Satisfaction Index 226 Happy Planet Index 237 Status of Women 246 Global Gender Gap Index 249 Culture and Arts 259 Etiquette 259 Travel Information 260 Diseases/Health Data 272 Chapter 6 278 Environmental Overview 278 Environmental Issues 279 Environmental Policy 280 Greenhouse Gas Ranking 281 Global Environmental Snapshot 292 Global Environmental Concepts 304 International Environmental Agreements and Associations 318 Appendices 342 Bibliography 343 Burma (Myanmar) Chapter 1 Country Overview Burma (Myanmar) Review 2016 Page 1 of 354 pages Burma (Myanmar) Country Overview BURMA (MYANMAR) The military authorities ruling this country have changed the historic name - Burma - to Union of Myanmar or Myanmar. -

TIMMAS30 94-07 UN Hearings.DOC

Documents on East Timor Volume 30: July 13-14, 1994 Special Issue: United Nations Decolonization Committee Hearings on East Timor Published by: East Timor Action Network / U.S. P.O. Box 1182, White Plains, NY 10602 USA Tel: 914-428-7299 Fax: 914-428-7383 E-mail [email protected] These documents are produced approximately every two months and mailed to subscribers. For additional or back copies, send US$25. per volume; add $3. for international air mail. Discounts: $10 for educational and non-profit institutions. Activist rate: $6. domestic, $8. international. Subscription rates: $150 ($60 educational, $36 activist) for the next six issues. Add $18 ($12 activist) for international air mail. Further subsidies are available for groups in Third World countries working on East Timor. Checks should be made out to “ETAN.” This material is also available on IBM-compatible diskette, in Word for Windows or ASCII format. Reprinting and distribution without permission is welcomed. TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................. 2 WORKING PAPER PREPARED BY THE U.N. SECRETARIAT ......................................................................... 3 I. GENERAL...............................................................................................................................................3 II. CONSIDERATION BY THE UNITED NATIONS 2 ......................................................................................3 -

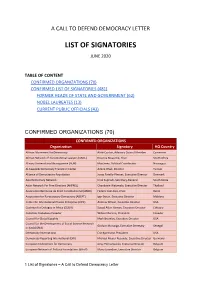

List of Signatories June 2020

A CALL TO DEFEND DEMOCRACY LETTER LIST OF SIGNATORIES JUNE 2020 TABLE OF CONTENT CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS (70) CONFIRMED LIST OF SIGNATORIES (481) FORMER HEADS OF STATE AND GOVERNMENT (62) NOBEL LAUREATES (13) CURRENT PUBLIC OFFICIALS (43) CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS (70) CONFIRMED ORGANIZATIONS Organization Signatory HQ Country African Movement for Democracy Ateki Caxton, Advisory Council Member Cameroon African Network of Constitutional Lawyers (ANCL) Enyinna Nwauche, Chair South Africa Alinaza Universitaria Nicaraguense (AUN) Max Jerez, Political Coordinator Nicaragua Al-Kawakibi Democracy Transition Center Amine Ghali, Director Tunisia Alliance of Democracies Foundation Jonas Parello-Plesner, Executive Director Denmark Asia Democracy Network Ichal Supriadi, Secretary-General South Korea Asian Network For Free Elections (ANFREL) Chandanie Watawala, Executive Director Thailand Association Béninoise de Droit Constitutionnel (ABDC) Federic Joel Aivo, Chair Benin Association for Participatory Democracy (ADEPT) Igor Botan, Executive Director Moldova Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) Andrew Wilson, Executive Director USA Coalition for Dialogue in Africa (CODA) Souad Aden-Osman, Executive Director Ethiopia Colectivo Ciudadano Ecuador Wilson Moreno, President Ecuador Council for Global Equality Mark Bromley, Executive Director USA Council for the Development of Social Science Research Godwin Murunga, Executive Secretary Senegal in (CODESRIA) Democracy International Eric Bjornlund, President USA Democracy Reporting International -

"Towards Peace and Democracy in Burma" European Parliament, 05Th October 2010 Speech Maria Da Graça Carvalho

"Towards Peace and Democracy in Burma" European Parliament, 05th October 2010 Speech Maria da Graça Carvalho His Excellency, President Ramos-Horta President Daul Ambassadors Members of the European Parliament Distinguished Guest Ladies and gentlemen, As a co-organiser of the present event and co-president of the Economic Development, Finance and Trade Committee of the ACP-UE Joint Parliamentary Assembly in the European Parliament, it is with great pleasure that I welcome President Ramos-Horta here today. President Ramos-Horta will be speaking about Burma and about peace and democracy in the country in particular. As you certainly know, Burma, as a military dictatorship has chronic problems with human rights abuses. These include: child abuse violation of the rights of minorities forced labour a degree of alleged corruption involving a number of multinationals according to human rights groups, the government still holds 2,200 political prisoners not allowing sufficient aid to enter the region affected by the Cyclone Nargis where more than 3 million were homeless and around 150,000 are thought to have died members of religious orders in Burma including an estimated 400 000 Buddhist monks, are explicitly banned from voting and a range of other problems too numerous to mention here. President Ramos-Horta's visit today is particularly timely in view of the elections due for the 7th of November. As you will know, these elections do not meet the minimum standards of a democracy: San Suu Kyi is still under house arrest and will remain so until after the elections. She has been detained for 14 of the past 20 years Individuals with foreign spouses cannot stand for elections 1/4 "Towards Peace and Democracy in Burma" European Parliament, 05th October 2010 Speech Maria da Graça Carvalho 25% of seats in the lower chamber are reserved for the military and so on and so forth. -

1 the East Timor Roofing Project

1 The East Timor Roofing Project A joint project of the Rotary Clubs of Doncaster, Melbourne and Lilydale, Districts 9810 and 9800. “When subsistence farmers were given a grain silo, they could feed their families and have a surplus to sell. This would give some of them money for the first time in their life.” Dr Frank Evans What started as just another Rotary project in the year 2000 to manufacture and install corrugated roofs for homes after the Indonesians retreated from East Timor, has become an amazing success story. The East Timor Roofing Project has raised enough money to build roofs on many schools, orphanages, community and commercial buildings and homes for East Timorese, over 2,000 water tanks and in excess of 1,000 grain silos, provide training for local East Timorese trainers, who themselves have trained over 250 East Timorese in building and administration skills. Over 12,500 tonnes of steel has been used to make the roofing and associated products. Equally amazing, the committee has been working methodically for over ten years to ensure the project was viable and to change direction when required to meet the needs of the local people. This story attempts to capture some of the lessons learnt by this committed band of Rotary volunteers, the manager and workers in East Timor. (Story told by Dr Frank Evans to Pat Armstrong, both of the Rotary Club of Doncaster) Facts about East Timor Also known as Timor-Leste Made up of part of the island of Timor, plus several other small islands Situated 640 km northwest of Darwin Population is 1,066,582 (2010) Literacy rate is 50% (2010) Life expectancy (2010) is 62 years Child mortality rate (2010; under 5)-is 64/1,000 (In Australia, life expectancy is 79.3 years for males and 83.9 years for females. -

Constitution of the Democratic Republic Of

CONSTITUTION OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF TIMOR-LESTE TIMOR-LESTE ______________________________________________________ INDEX Preamble PART I FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES Sections 1 The Republic 2 Sovereignty and constitutionality 3 Citizenship 4 Territory 5 Decentralisation 6 Objectives of the State 7 Universal suffrage and multi-party system 8 International relations 9 International law 10 Solidarity 11 Valorisation of Resistance 12 State and religious denominations 13 Official languages and national languages 14 National symbols 15 National flag PART II FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS, DUTIES, LIBERTIES AND GUARANTEES TITLE I GENERAL PRINCIPLES 16 Universality and equality 17 Equality between women and men 18 Child protection 19 Youth 20 Senior citizens 21 Disabled citizen 22 East Timorese citizens overseas 23 Interpretation of fundamental rights 24 Restrictive laws 25 State of exception 26 Access to courts 27 Ombudsman 28 Right to resistance and self-defence TITLE II PERSONAL RIGHTS, LIBERTIES AND GUARANTEES 29 Right to life 30 Right to personal freedom, security and integrity 31 Application of criminal law 32 Limits on sentences and security measures 33 Habeas Corpus 34 Guarantees in criminal proceedings 35 Extradition and expulsion 36 Right to honour and privacy 37 Inviolability of home and correspondence 38 Protection of personal data 39 Family, marriage and maternity 40 Freedom of speech and information 41 Freedom of the press and mass media 42 Freedom to assemble and demonstrate 43 Freedom of association 44 Freedom of movement 45 Freedom of conscience, -

José Ramos-Horta

www.FAMOUS PEOPLE LESSONS.com JOSÉ RAMOS-HORTA http://www.famouspeoplelessons.com/j/jose_ramos-horta.html CONTENTS: The Reading / Tapescript 2 Synonym Match and Phrase Match 3 Listening Gap Fill 4 Choose the Correct Word 5 Spelling 6 Put the Text Back Together 7 Scrambled Sentences 8 Discussion 9 Student Survey 10 Writing 11 Homework 12 Answers 13 JOSÉ RAMOS-HORTA THE READING / TAPESCRIPT José Ramos-Horta (born 1949) is the second Prime Minister of East Timor and a Nobel Peace Prize winner. He has spent most of his life fighting for and serving his people. He was a founder of a group that fought against the Indonesian occupation of his country between 1975 and 1999. He was injured in an assassination attempt in 2008. Ramos-Horta was involved in politics from a young age. When he was 25, he became Foreign Minister of the "Democratic Republic of East Timor". Three days after he arrived in New York to talk about independence for his country, Indonesian troops invaded and took over East Timor. He pleaded with the UN Security Council to end Indonesia’s occupation, in which 102,000 East Timorese died. Ramos-Horta travelled the world for two decades to raise awareness of what was happening in East Timor. He often had hardly a penny in his pocket and relied on the goodwill of well-wishers. He got the Nobel Prize in 1996 for his "sustained efforts to hinder the oppression of a small people”. Several years later, East Timor would be free. Ramos-Horta played a key role in negotiating East Timor’s independence. -

US to Timor Leste April 6-14, 2019

US to Timor Leste April 6-14, 2019 Exchange Guide This exchange is made possible through a grant from the Government of Timor Leste. Table of Contents Schedule ........................................................................................................................ 3 Schedule Notes ............................................................................................................. 9 Delegate Biographies ................................................................................................. 13 Program Contact Information ................................................................................... 18 Flight Confirmations and Itineraries ........................................................................... 19 Schedule Saturday, April 6 Depart from home airports Monday, April 8 Sydney, Australia/Darwin/Dili, Timor Leste 9:20am Qantas Airways #840 departs Sydney Airport 1:30pm Arrive at Darwin International Airport 2:10pm Qantas Airways #369 departs Darwin 4:20pm Arrive at Presidente Nicolau Lobato International Airport **Jessica Woolley (574) 536-8863) will meet you at the airport** 5:00pm Depart for hotel 5:30pm Arrive at and check in to hotel: Novo Tourismo Avenue Bidau, Lecidere 6:15pm Meet in hotel lobby 6:30pm Dinner at hotel with Ms. Jessica Woolley Policy Advisor, DLA Piper Also in attendance will be: Ms. Fiona Macrae Senior Information and Communications Adviser, Maritime Boundary Office Tuesday, April 9 Dili Attire: Business casual Breakfast: At the hotel 7:15am Meet in hotel lobby 7:30am -

Benedict's Jesus

June 4-11,America 2007 THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WEEKLY $2.75 Benedict’s Jesus Gerald O’Collins reviews the pope’s new book Olga Bonfiglio on hope in El Salvador Carl Anderson on faith in the Americas George Anderson interviews Martin Maier of ‘Stimmen der Zeit’ The 2007 Foley Award Poem America OU MAY NOT HAVE NOTICED, but the duties at America, Charlie also found time to Published by Jesuits of the United States listing of associate editors on the serve as in-house counsel to a series of Jesuit masthead of this journal is deter- editors in chief. His paralegal expertise—on Editor in Chief mined by seniority. When I returned such questions as the proper mixing of mint Drew Christiansen, S.J. Yfrom the Philippines in the Spring of 1972 to juleps on Kentucky Derby Day—was also join the staff, my name was added at the end sought and appreciated by the America House Managing Editor of a list of seven other Jesuits who had pre- Jesuit community. Robert C. Collins, S.J. ceded me. Immediately ahead of me was John Like Charlie Whelan, John Donohue has W. Donohue, who had joined the staff earlier had long and lasting links to Fordham Business Manager that year; and second from the top, following University. After earning his doctorate in Lisa Pope Vincent S. Kearney, was Charles M. Whelan. education from Yale University, John joined Charlie Whelan had joined the staff in 1962; the faculty of Fordham’s Graduate School of Editorial Director since Father Kearney’s death in 1981, he has Education and published what is regarded as a Karen Sue Smith presided at the head of the list as the senior classic study of the Jesuit philosophy of edu- associate editor.