Delhi's Dynasts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Petroleum Technology Jais, Amethi, Uttar Pradesh

RAJIV GANDHI INSTITUTE OF PETROLEUM TECHNOLOGY JAIS, AMETHI, UTTAR PRADESH APPLICATION FOR CANCELLATION & WITHDRAWAL OF ADMISSION SESSION: _____________________ Date: To, The Director / Registrar Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Petroleum Technology Jais, Amethi-229304 Uttar Pradesh Through: a) Associate Dean (Academic Affairs) b) Chairman UG/PG Admission Committee c) Head of Department /Concerned Student’s PhD Supervisor Sir, I was s h o rt l is ted & s ec u r ed admission to the B. Tech. /M. Tech. /Ph. D./MBA/Others Program’s in your Institute on ______. I would like to cancel and withdrawal my candidature it due to the following reasons: ______________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________ 1) Name of the Candidate: Ms. / Mr. (IN BLOCK LETTERS) (Name) (Surname) 2) Father’s Name: Mr. / Dr. 3) RGIPT Registration No.: 4) IIT JEE/GATE/CAT Roll No.: Mubarakpur, Mukhetia, Bahadurpur, Post: Harbanshganj, Jais, Amethi-229304 (Uttar Pradesh) Phone: -

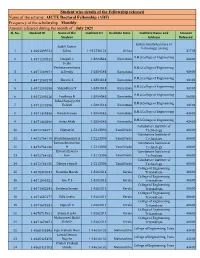

Student Wise Details of the Fellowship Released Name of the Scheme

Student wise details of the Fellowship released Name of the scheme: AICTE Doctoral Fellowship (ADF) Frequency of the scholarship –Monthly Amount released during the month of : July 2021 Sl. No. Student ID Name of the Institute ID Institute State Institute Name and Amount Student Address Released Indira Gandhi Institute of Sushil Kumar Technology, Sarang 1 1-4064399722 Sahoo 1-412736121 Orissa 31703 B.M.S.College of Engineering 2 1-4071237529 Deepak C 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Perla Venkatasreenivasu B.M.S.College of Engineering 3 1-4071249071 la Reddy 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 4 1-4071249170 Shruthi S 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 5 1-4071249196 Vidyadhara V 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 6 1-4071249216 Pruthvija B 1-5884543 Karnataka 86800 Tulasi Naga Jyothi B.M.S.College of Engineering 7 1-4071249296 Kolanti 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 8 1-4071448346 Manali Raman 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 9 1-4071448396 Anisa Aftab 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Coimbatore Institute of 10 1-4072764071 Vijayan M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 11 1-4072764119 Sivasubramani P A 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Ramasubramanian Coimbatore Institute of 12 1-4072764136 M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Eswara Eswara Coimbatore Institute of 13 1-4072764153 Rao 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 14 1-4072764158 Dhivya Priya N 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 -

Indian Military Procurements: a Scandalous Affair

Indian military procurements: a scandalous affair Dr Zia Ul Haque Shamsi India, the world’s largest democracy and a non-NPT nuclear weapons’ state, is plagued with scandals for military procurements. Despite stringent and painstaking bureaucratic processes for the approvals of defence procurements, India has perhaps the most numbers of scandals of corruptions when it comes to buying arms and equipment. The most famous corruption scandal in Indian military procurements remains that of Swedish Bofors guns during the 1980s. As the narrative goes, Indian military acquired some 410 field howitzer guns of 155 mm calibre from a Swedish firm Bofors AB for USD 1.4 billion. While the selection of the equipment was not questioned, nor the contract package, but it was revealed much later that millions of dollars were paid by the Swedish company to Indian politicians to secure the contract. This bombshell news was actually broken by the Swedish radio on April 16, 1987. The news was immediately reported in Indian media and had an extremely adverse impact on Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, who in fact lost the general elections held in November 1989. Interestingly, Janta Dal leader VP Singh who was Gandhi’s Defence Minister when the Bofors scandal broke the ground and had resigned, became India’s Prime Minister in the aftermath of disastrous results for Indian National Congress (INC). Another Indian military acquisition deal which came to light due to allegations of bribery by the international vendor relates to Thales’ Scorpene-class submarines. The alleged amount was USD 175 million in a total contract deal of USD 3.0 billion, which was made through a middleman. -

State: Uttar Pradesh Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: Amethi

State: Uttar Pradesh Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: Amethi 1.0 District Agriculture profile 1.1 Agro-Climatic/ Ecological Zone Agro-Ecological Sub Region(ICAR) North plain zone Agro-Climatic Zone (Planning Commission) Upper Gangetic Plain Region Agro-Climatic Zone (NARP) UP-4 Central Plain Zone List all the districts falling the NARP Zone* (^ 50% area Lakhimpur, Kheri, Sitapur, Hardoi, Farrukhabad, Etawah, Kanpur, Kanpur Dehat, Unnao, falling in the zone) Lucknow, Rae Bareilly, Fatehpur Geographical coordinates of district headquarters Latitude Latitude Latitude 26.55N 81.12E Name and address of the concerned - ZRS/ZARS/RARS/RRS/RRTTS Mention the KVK located in the district with address Name and address of the nearest Agromet Field C.S.Azad University of Agriculture & Technology Unit(AMFU,IMD)for agro advisories in the Zone 1.2 Rainfall Normal RF (mm) Normal Rainy Normal Onset Normal Cessation Days (Number) (Specify week and month) (Specify week and month) SW monsoon (June-sep) 855.9 49 2nd week of June 4th week of September Post monsoon (Oct-Dec) 49.4 10 Winter (Jan-March) 42.3 10 - - Pre monsoon (Apr-May) 16.5 2 - - Annual 964.0 71 1.3 Land use pattern Geographical Cultivable Forest Land under Permanent Cultivable Land Barren and Current Other of the district area area area non- pastures wasteland under uncultivable fallows fallows (Latest agricultural Misc.tree land statistics) use crops and groves Area in (000 ha) 307.0 250.9 1.4 40.7 2.4 7.0 10.2 11.5 24.1 15.7 1.4 Major Soils Area(‘000 ha) Percent(%) of total Deep, loamy -

NDTV Pre Poll Survey - U.P

AC PS RES CSDS - NDTV Pre poll Survey - U.P. Assembly Elections - 2002 Centre for the Study of Devloping Societies, 29 Rajpur Road, Delhi - 110054 Ph. 3951190,3971151, 3942199, Fax : 3943450 Interviewers Introduction: I have come from Delhi- from an educational institution called the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (give your university’s reference). We are studying the Lok Sabha elections and are interviewing thousands of voters from different parts of the country. The findings of these interviews will be used to write in books and newspapers without giving any respondent’s name. It has no connection with any political party or the government. I need your co-operation to ensure the success of our study. Kindly spare some ime to answer my questions. INTERVIEW BEGINS Q1. Have you heard that assembly elections in U.P. is to be held in the next month? 2 Yes 1 No 8 Can’t say/D.K. Q2. Have you made up your mind as to whom you will vote during the forth coming elections or not? 2 Yes 1 No 8 Can’t say/D.K. Q3. If elections are held tomorrow it self then to whom will cast your vote? Please put a mark on this slip and drop it into this box. (Supply the yellow dummy ballot, record its number & explain the procedure). ________________________________________ Q4. Now I will ask you about he 1999 Lok Sabha elections. Were you able to cast your vote or not? 2 Yes 1 No 8 Can’t say/D.K. 9 Not a voter. -

Accidental Prime Minister

THE ACCIDENTAL PRIME MINISTER THE ACCIDENTAL PRIME MINISTER THE MAKING AND UNMAKING OF MANMOHAN SINGH SANJAYA BARU VIKING Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Group (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Offi ce Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Johannesburg 2193, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offi ces: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England First published in Viking by Penguin Books India 2014 Copyright © Sanjaya Baru 2014 All rights reserved 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him which have been verifi ed to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same. ISBN 9780670086740 Typeset in Bembo by R. Ajith Kumar, New Delhi Printed at Thomson Press India Ltd, New Delhi This book is sold subject to the condition that -

India: the Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India

ASARC Working Paper 2009/06 India: The Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India Desh Gupta, University of Canberra Abstract This paper explains the complex of factors in the weakening of the Congress Party from the height of its power at the centre in 1984. They are connected with the rise of state and regional-based parties, the greater acceptability of BJP as an alternative in some of the states and at the Centre, and as a partner to some of the state-based parties, which are in competition with Congress. In addition, it demonstrates that even as the dominance of Congress has diminished, there have been substantial improvements in the economic performance and primary education enrolment. It is argued that V.P. Singh played an important role both in the diminishing of the Congress Party and in India’s improved economic performance. Competition between BJP and Congress has led to increased focus on improved governance. Congress improved its position in the 2009 Parliamentary elections and the reasons for this are briefly covered. But this does not guarantee an improved performance in the future. Whatever the outcomes of the future elections, India’s reforms are likely to continue and India’s economic future remains bright. Increased political contestability has increased focus on governance by Congress, BJP and even state-based and regional parties. This should ensure improved economic and outcomes and implementation of policies. JEL Classifications: O5, N4, M2, H6 Keywords: Indian Elections, Congress Party's Performance, Governance, Nutrition, Economic Efficiency, Productivity, Economic Reforms, Fiscal Consolidation Contact: [email protected] 1. -

A Number of Decisions Made by the Rajiv Gandhi Government

Back to the Future: The Congress Party’s Upset Victory in India’s 14th General Elections Introduction The outcome of India’s 14th General Elections, held in four phases between April 20 and May 10, 2004, was a big surprise to most election-watchers. The incumbent center-right National Democratic Alliance (NDA) led by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), had been expected to win comfortably--with some even speculating that the BJP could win a majority of the seats in parliament on its own. Instead, the NDA was soundly defeated by a center-left alliance led by the Indian National Congress or Congress Party. The Congress Party, which dominated Indian politics until the 1990s, had been written off by most observers but edged out the BJP to become the largest party in parliament for the first time since 1996.1 The result was not a complete surprise as opinion polls did show the tide turning against the NDA. While early polls forecast a landslide victory for the NDA, later ones suggested a narrow victory, and by the end, most exit polls predicted a “hung” parliament with both sides jockeying for support. As it turned out, the Congress-led alliance, which did not have a formal name, won 217 seats to the NDA’s 185, with the Congress itself winning 145 seats to the BJP’s 138. Although neither alliance won a majority in the 543-seat lower house of parliament (Lok Sabha) the Congress-led alliance was preferred by most of the remaining parties, especially the four-party communist-led Left Front, which won enough seats to guarantee a Congress government.2 Table 1: Summary of Results of 2004 General Elections in India. -

ALLAHABAD Address: 38, M.G

CGST & CENTRAL EXCISE COMMISSIONERATE, ALLAHABAD Address: 38, M.G. Marg, Civil Lines, Allahabad-211 001 Phone: 0532-2407455 E mail:[email protected] Jurisdiction The territorial jurisdiction of CGST and Central Excise Commissionerate Allahabad, extends to Districts of Allahabad, Banda, Chitrakoot, Kaushambi, Jaunpur, SantRavidas Nagar, Pratapgarh, Raebareli, Fatehpur, Amethi, Faizabad, Ambedkarnagar, Basti &Sultanpurof the state of Uttar Pradesh. The CGST & Central Excise Commissionerate Allahabad comprises of following Divisions headed by Deputy/ Assistant Commissioners: 1. Division: Allahabad-I 2. Division: Allahabad-II 3. Division: Jaunpur 4. Division: Raebareli 5. Division: Faizabad Jurisdiction of Divisions & Ranges: NAME OF JURISDICTION NAME OF RANGE JURISDICTION OF RANGE DIVISION Naini-I/ Division Naini Industrial Area of Allahabad office District, Meja and Koraon tehsil. Entire portion of Naini and Karchhana Area covering Naini-II/Division Tehsil of Allahabad District, Rewa Road, Ranges Naini-I, office Ghoorpur, Iradatganj& Bara tehsil of Allahabad-I at Naini-II, Phulpur Allahabad District. Hdqrs Office and Districts Jhunsi, Sahson, Soraon, Hanumanganj, Phulpur/Division Banda and Saidabad, Handia, Phaphamau, Soraon, Office Chitrakoot Sewait, Mauaima, Phoolpur Banda/Banda Entire areas of District of Banda Chitrakoot/Chitrako Entire areas of District Chitrakoot. ot South part of Allahabad city lying south of Railway line uptoChauphatka and Area covering Range-I/Division Subedarganj, T.P. Nagar, Dhoomanganj, Ranges Range-I, Allahabad-II at office Dondipur, Lukerganj, Nakhaskohna& Range-II, Range- Hdqrs Office GTB Nagar, Kareli and Bamrauli and III, Range-IV and areas around GT Road. Kaushambidistrict Range-II/Division Areas of Katra, Colonelganj, Allenganj, office University Area, Mumfordganj, Tagoretown, Georgetown, Allahpur, Daraganj, Alopibagh. Areas of Chowk, Mutthiganj, Kydganj, Range-III/Division Bairahna, Rambagh, North Malaka, office South Malaka, BadshahiMandi, Unchamandi. -

Indian National Congress Sessions

Indian National Congress Sessions INC sessions led the course of many national movements as well as reforms in India. Consequently, the resolutions passed in the INC sessions reflected in the political reforms brought about by the British government in India. Although the INC went through a major split in 1907, its leaders reconciled on their differences soon after to give shape to the emerging face of Independent India. Here is a list of all the Indian National Congress sessions along with important facts about them. This list will help you prepare better for SBI PO, SBI Clerk, IBPS Clerk, IBPS PO, etc. Indian National Congress Sessions During the British rule in India, the Indian National Congress (INC) became a shiny ray of hope for Indians. It instantly overshadowed all the other political associations established prior to it with its very first meeting. Gradually, Indians from all walks of life joined the INC, therefore making it the biggest political organization of its time. Most exam Boards consider the Indian National Congress Sessions extremely noteworthy. This is mainly because these sessions played a great role in laying down the foundational stone of Indian polity. Given below is the list of Indian National Congress Sessions in chronological order. Apart from the locations of various sessions, make sure you also note important facts pertaining to them. Indian National Congress Sessions Post Liberalization Era (1990-2018) Session Place Date President 1 | P a g e 84th AICC Plenary New Delhi Mar. 18-18, Shri Rahul Session 2018 Gandhi Chintan Shivir Jaipur Jan. 18-19, Smt. -

Indira Ghandi

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 36 Date 12/06/2006 Time 2:11:31 PM S-0882-0001-36-00001 Expanded Number S-0882-0001-36-00001 Title items-in-lndia - Indira Ghandi Date Created 19/01/1966 Record Type Archival Item Container S-0882-0001: Correspondence Files of the Secretary-General: U Thant: with Heads of State, Governments, Permanent Representatives and Observers to the United Nations Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit 19 January 1966 Bsar Hr* 2be Secretary-General"would be grateful ±f you would Kindly transmit the enclosed personal letter from. him to Her Excellency the I*r3bne Minister. Yours e Bola-Bennett Sbder-Seeretary for Special l^litical Affairs %* Br^esh '€., Hislira , Deputy §ermaneKb Representative of India to the tJnited Nations 5 Sast 6«H;a Street Sew York 21, lew. Torfe RM 19 Itear Hease allow w& to extend to yoa my wsraest personal congratulations OK your designation as the Prime Minister of India. I sen convinced -feat your great country has chosen well in selecting you, through its traditionally democratic processes, to he t&e Bead of its Governraeat- flhile I am equally convinced that your own goalities and experience in the affairs of State have ty themselves earned for ysu the eoafMenee of the people of India ia your ability to lead them, I also rejoice at the fiirther distinction you have brosgfot, on the one hand, to the family of your illustrious father and, on the other hand, to womanMod the world over. Knowing something of the extent of the responsibilities you are assuming tjoth for the welfare aacl the progress of your country and for the iicmeaBely important role it esa play in the affairs of Asia and the world, X offer you ray jaost sincere good -wishes snd all the support amd eneottrageifflefit of which 1 am capable* 2 recall with parti culsr pleasure oiar meeting last September j aad look forward to the contintistioB of our association.