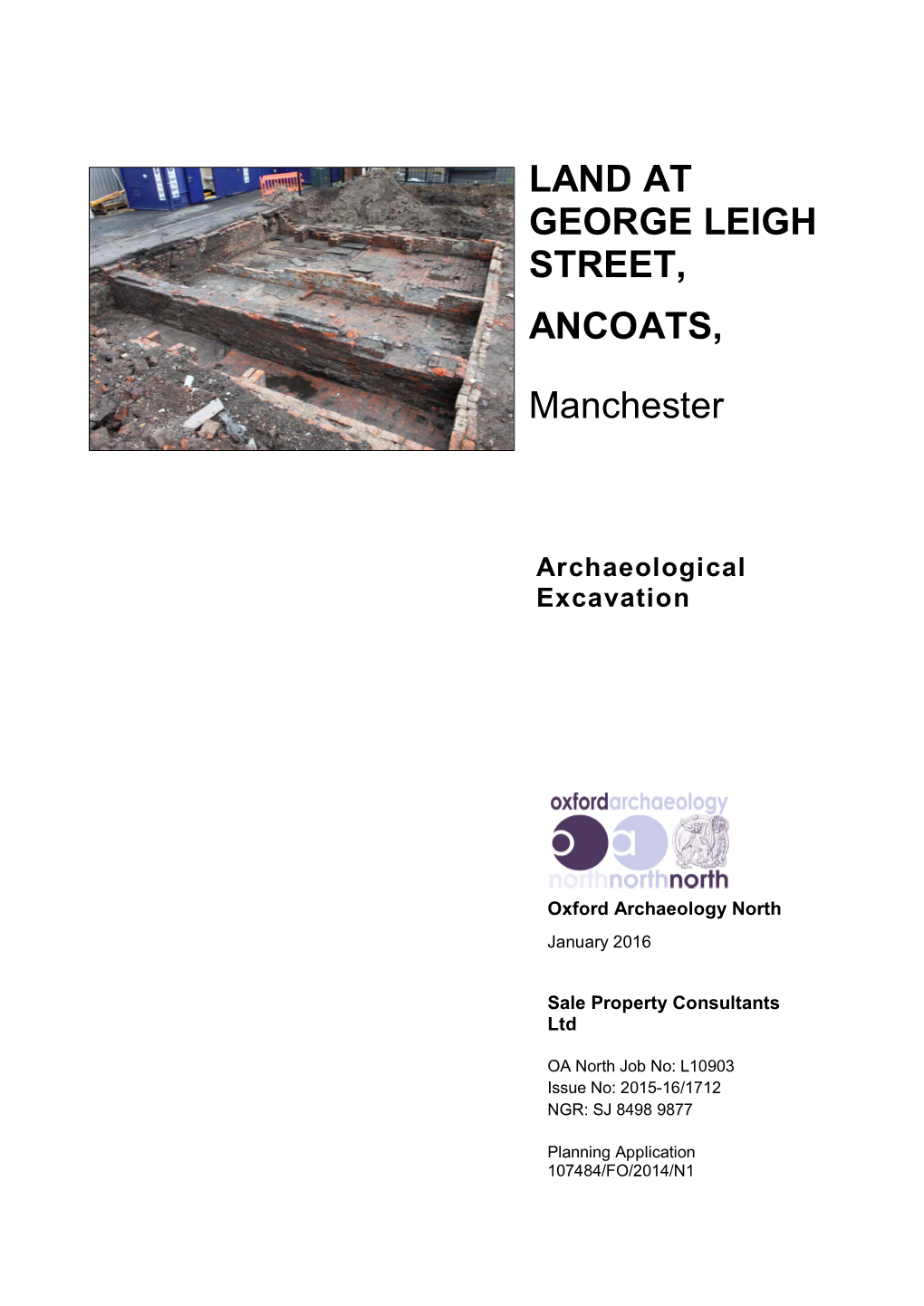

Land at George Leigh Street, Ancoats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Wettelijke Aspecten Van De Strijd Tegen De Waterverontreiniging in België

IR. W. A. H. BROUWER R1ZA, Voorburg De wettelijke aspecten van de strijd tegen de waterverontreiniging in België Nu reeds bijna 2 jaar ervaring is ver 3. De oprichting van rioolwaterzuive openbare wateren van afvalwater, dat kregen met de Wet Verontreiniging Op ringsinstallaties te bevorderen en van de gemeenteriolen afkomstig is. Voor pervlaktewateren in Nederland, is het hiervoor eventueel de oprichting van deze categorie afvalwater voorziet de wellicht nuttig de stand van zaken met intercommunale verenigingen uit te wet van 11 maart 1950 niet in een betrekking tot de wetgeving over de be lokken. lozingsvergunning. Volgens het politie- scherming van oppervlaktewateren tegen 4. De nodige wettelijke en reglementaire reglement op de Scheepvaartwegen is de verontreiniging in andere landen na te teksten voor te bereiden. lozing van afvalwater aan een vergun gaan. Om nu maar eens „dicht bij huis" ning onderhevig, zodat voor de lozing te beginnen: hoe was en is de situatie Naar aanleiding van deze voorstellen van rioolwater op de scheepvaartwegen dienaangaande bij onze Zuiderburen? werd bij Koninklijk Besluit van 22 maart een vergunning vereist is van de Minister In de wet van 7 mei 1877 op de onbe 1934 de Dienst voor Zuivering van Af van Openbare Werken. Art. 4 bepaalt vaarbare waterlopen, in de wet van valwater opgericht, die eerst onder het dat de Minister van Volksgezondheid 7 oktober 1886 (het landelijke wetboek), Ministerie van Openbare Werken werd en van het Gezin op elk ogenblik een ge in de wet van 5 mei 1888 op de vergun- geplaatst, maar sinds 1939 onder het meente kan aanzeggen binnen de door ningsplichtige inrichtingen en in het poli- Ministerie van Volksgezondheid en van hem bepaalde termijn tot de oprichting tiereglement op de door de Staat be het Gezin ressorteert. -

The Victorian Society in Manchester Registered Charity No

The Victorian Society in Manchester Registered Charity No. 1081435 Registered Charity No.1081435 Summer Newsletter 2014 EDITORIAL has, indeed, been the subject for in other comments on the question of monographic books by Ian he clearly distinguished between the Toplis (1987) and Bernard Porter ‘Greek’ idiom of the ancient world THE BATTLE OF THE STYLES (2011) – as well as of a number of and the ‘Italian’ of the Renaissance. CONTINUED? scholarly articles, beginning with What he surely meant was a building David Brownlee’s ‘That regular in the Victorian Italianate style which, Anyone with more than a passing mongrel affair’ in 1985. Brownlee by the end of the 1850s, had become interest in Victorian architecture will conceptualized the contretemps as the expressive idiom for a far greater know about the ‘battle of the styles’ the moment when the High Victorian proportion of British architecture than that began at the start of the Queen’s movement in architecture was derailed was encompassed by neo-Gothic reign and reached its climax with by an elderly survivor (Palmerston was churches, educational buildings and the commission for new government 76 in 1860) of the earlier nineteenth- the like. It was an idiom that had just offices on Whitehall between 1856 and century Reform movement, whose as much right as the Gothic Revival 1860. The three-section competition, architectural ideas were retrogressively to claim to represent ‘the modern launched during Lord Palmerston’s late Georgian. Although more school of English architecture’, as first administration, resulted in victories nuanced interpretations have emerged W.H. Leeds called it in the title of for little-known architects peddling subsequently, that idea has basically his 1839 monograph on Charles versions of contemporary Parisian stuck. -

New Carrington Historic Environment Assessment Appendix 1

Historic Environment Assessment GMSF Land Allocations, Trafford GMA45 New Carrington Appendix 1 (Historic Environment Background and Characterisation) Client: Trafford Council Technical Report: Anthony Lee & Rachael Reader Report No: 2020/4 Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Methodology 7 3. The Site 13 4. Historical Background 15 5. Characterisation of the Historic Environment 31 6. Sources 64 7. Acknowledgements 72 8. Figures 73 9. Gazetteer 75 1. Introduction 1.1 Introduction This Appendix presents the planning background and methodology for the assessment ofthe New Carrington land allocation area (herein referred to as ‘the Site’), an overview of the historical background to the Site, and identifies and describes the Historic Environment Character Areas (HECAs) into which the Site has been usefully divided. A total of 22 HECAs have been defined, as well a number of designated built heritage assets within, and in close proximity to, the Site. These, along with the undesignated built heritage, have been subject to significance assessments, including considerations of setting (Appendix 3). The archaeological sensitivity and potential are concentrated particularly in and around Warburton Park, and within the former moss and the undeveloped areas of the mossland fringe (Appendix 2). Areas of enhancement have also been identified, where it is recommended that consideration is given to the opportunity for incorporating and preserving elements of the historic environment within the masterplan for the site (Appendix 4). 1.2 Planning Background In October 2019, the Centre for Applied Archaeology was commissioned by Trafford Council to undertake a detailed historic environment assessment of the Site, which has been identified for development within the Greater Manchester Spatial Framework (GMSF). -

Trafford Local Plan: Land Allocations – Consultation Draft

TRAFFORD COUNCIL Report to: Planning Development Control Committee Date: 13 th February 2014 Report for: Information Report of: Head of Planning Services Report Title Trafford Local Plan: Land Allocations – Consultation Draft Summary This report presents the Trafford Local Plan: Land Allocations Consultation Draft document to the Planning Development Control Sub Committee. The Land Allocations Plan has been developed to support the delivery of the Trafford Local Plan: Core Strategy. Upon adoption it will set out new site allocations for a variety of land uses including housing, employment and open spaces. Recommendation That Members of Planning and Development Control Committee note the publication of the Trafford Local Plan: Land Allocations – Consultation Draft. Contact person for access to background papers and further information: Name: Rob Haslam (Head of Planning) Extension: 4788 Background Papers: Trafford Local Plan: Land Allocations – Consultation Draft and associated evidence documents which can be found at: http://www.trafford.gov.uk/planning/strategic- planning/local-development-framework/trafford-local-plan-land-allocations.aspx 1.0 Background 1.1 The Trafford Local Plan: Land Allocations Development Plan Document (LAP) will provide site-specific guidance for the development of allocated sites and areas and will provide more general development management guidance; it is accompanied by a Policies Map. It covers the whole borough, except that area subject to the proposed Altrincham Business Neighbourhood Plan. 1.2 The purpose of the Trafford LAP is to: • identify and prioritise the sites necessary to meet the sustainable needs of the borough; 1 • Identify the natural and built assets which should be protected/enhanced; • Identify the key design, environmental and infrastructure requirements for allocated sites and; • Ensure that new development is delivered within an identified timescale. -

The Extensions to the Davyhulme Sewage Works

7041 The extensions to theDavyhulme Sewage Works (1 957-67) The Paper describes the design and construction of extensions to the Davyhulme Sewage Works which have been carried out over the past ten years at a cost of approximately E6 million.These extensions comprise inlet works, primary sedi- mentation plant, a 45 mgd Simplex aeration plant, final sedimentation tanks, storm sewage tanks, primary sludge digestion plant, secondary sludge thickening plant, power generation plant and jetties. A general accountof the whole plant is given with a more detailed description of those features which the Author considers to be of particular interest. A list of the contractors and a table of costs are appended. Introduction In 1954, when the new extensions were first considered,the Davyhulme Sewage Works consisted of two separateplants with a common inlet works. An activated sludge plant completed in 1934, comprising a diffused air unit and small experimental unitson theSheffield Bio-aerationand the Simplex systems, treated a dry weather flowof 19 mgd and theremaining 35 mgd weretreated on primary and secondary contact beds completed in 1907. These beds were in very poor condition and the effluent quality was bad. 2. The City Council therefore decidedto retain theexisting activated sludge plant and to replace the contact beds by a new plant with a dry weather flow capacity of 45 mgd bringing the total capacity of the Works to 64 mgd. 3. In fact the rate of flow has risen more quickly than forecast and at the present time the dry weather flow is 68 mgd of which 24 mgd is trade waste. -

Natural Environment

Trafford Local Plan February 2021 Regulation 18 Consultation Draft The Trafford Local Plan - Consultation Draft - January 2021 Contents Table of Contents Contents ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 3 2. The Greater Manchester Spatial Framework 2020 ................................................................................. 6 3. Setting the scene ..................................................................................................................................... 7 4. Key Diagram ............................................................................................................................................ 9 5. Vision for Trafford .................................................................................................................................. 10 6. Strategic Objectives ............................................................................................................................... 11 7. Table of policies ..................................................................................................................................... 13 8. Trafford’s Places .................................................................................................................................... 16 9. Areas -

Maps, Memories and Manchester: the Cartographic Imagination of the Hidden Networks of the Hydraulic City

Paper for Mapping, Memory and the City: An International Interdisciplinary Conference. University of Liverpool, 25-26th February 2010. Maps, Memories and Manchester: The Cartographic Imagination of the Hidden Networks of the Hydraulic City Martin Dodge and Chris Perkins Department of Geography, University of Manchester (Email: [email protected]; [email protected]) Abstract The largely unseen channelling, culverting and controlling of water into, through and out of cities is the focus of our cartographic interpretation. This paper draws on empirical material depicting hydraulic infrastructure underlying the growth of Manchester in mapped form. Focusing, in particular, on the 19th century burst of large-scale hydraulic engineering, which supplied vastly increased amounts of clean drinking water, controlled unruly rivers to eliminate flooding, and safely removed sewage, this paper explores the contribution of mapping to the making of a more sanitary city, and towards bold civic minded urban intervention. These extensive infrastructures planned and engineered during Victorian and Edwardian Manchester are now taken-for-granted but remain essential for urban life. The maps, plans and diagrams of hydraulic Manchester fixed particular forms of elite knowledge (around planning foresight, topographical precision, civil engineering and sanitary science) but also facilitated and freed flows of water throughout the city. The survival of these maps and plans in libraries, technical books and obscure reports allows the changing cultural work of water to be explored and evokes a range of socially specific memories of a hidden city. Our aetiology of hydraulic cartographics is conducted using ideas from science and technology studies, semiology, and critical cartography with the goal of revealing how they work as virtual witnesses to an 1 unseen city, dramatizing engineering prowess and envisioning complex and messy materiality into a logical, holistic and fluid network underpinning the urban machine. -

Phd Thesis 2016

URBAN WASTEWATER TREATMENT WITH MATURE CONSTRUCTED WETLANDS Design and operation of experimental vertical-flow constructed wetland applied for treatment of urban wastewater (with/without diesel spills contamination), and recycling of effluent for agriculture purposes RAWAA HUSSEIN KADHIM AL-ISAWI PhD Thesis 2016 URBAN WASTEWATER TREATMENT WITH MATURE CONSTRUCTED WETLANDS Design and operation of experimental vertical-flow constructed wetland applied for treatment of urban wastewater (with/without diesel spills contamination), and recycling of effluent for agriculture purposes RAWAA HUSSEIN KADHIM AL-ISAWI School of Computing, Science and Engineering University of Salford, Salford, UK Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Civil Engineering December 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................ I LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................... IV LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................ IX ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................... XII DECLARATION: LIST OF ORIGINAL PAPERS AND CONFERENCES ..... XIV ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................. XXI ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................. -

Copy of Report Submitted to the Planning Panel at Their Meeting on 16Th April, 2009

PLANNING & TRANSPORTATION REGULATORY PANEL PART I SECTION 1: APPLICATIONS FOR PLANNING PERMISSION 16th April 2009 COPY OF REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE PLANNING PANEL AT THEIR MEETING ON 16TH APRIL, 2009 APPLICATION No: 03/47344/EIAHYB APPLICANT: Peel Investments (North) Limited LOCATION: Land Between Mid-point Of Manchester Ship Canal And Liverpool Road Liverpool Road Eccles PROPOSAL: Multi-modal freight interchange comprising rail served distribution warehousing, rail link and sidings, inter-modal and ancillary facilities including a canal quay and berths, vehicle parking, hardstanding, landscaping, re-routing of Salteye Brook, a new signal controlled access to the A57 and related highway works including realignment of the A57 and improvements to the M60 (Port Salford). Canal crossing and associated roads and other highway improvements as part of the Western Gateway Infrastructure Scheme (WGIS) WARD: Barton EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Introduction 1.1 For ease of reference, this report is split into three sections. Firstly, the background report contains details on the context of this application, a description of the proposed works, along with the consultation exercise undertaken and relevant national, regional and local policies. Secondly, the planning appraisal and thirdly, the Article 10 application and consultation received from Trafford Council concerning the element of the development that falls in Trafford. 2 Site description 2.1 This application relates to an irregular shaped parcel of land of approximately 116 hectares located to the north of the Manchester Ship Canal and approximately 2 km west of the M60 motorway. The site is considered in three broad areas: PLANNING & TRANSPORTATION REGULATORY PANEL PART I SECTION 1: APPLICATIONS FOR PLANNING PERMISSION 16th April 2009 2.2 Area A: This is approximately rectangular and is located south of the A57 and north of the Manchester Ship Canal; it is approximately 550m wide and 1.2 kilometres in length. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Planning and Transportation

Public Document Pack Planning and Transportation Regulatory Panel Dear Member, You are invited to attend the meeting of the Planning and Transportation Regulatory Panel to be held as follows for the transaction of the business indicated. Sian Roxborough Proper Officer DATE: Thursday, 17 December 2020 TIME: 9.30 am VENUE: Remote Meeting via MS Teams Live – please see the link below: In accordance with ‘The Openness of Local Government Bodies Regulations 2014,’ the press and public have the right to film, video, photograph or record this meeting. This meeting will be live-streamed. Members attending this meeting with a personal interest in an item on the agenda must disclose the existence and nature of that interest and, if it is a prejudicial interest, withdraw from the meeting during the discussion and voting on the item. There is likely to be a break for Panel Members, the time of which will be determined during the meeting. The items for consideration may not be heard in the order listed below. AGENDA THIS MEETING CAN BE VIEWED VIA THE LINK BELOW: This link will work if you are using a Microsoft device. If you are using an Apple or android based device, you will need to download the Microsoft Teams app in order to view the meeting via this link. https://teams.microsoft.com/l/meetup- join/19%3ameeting_ZjA1M2M4NzMtY2ZiYS00YjNhLWI2MzItNzI3Mm Q2ZmNjMmQ2%40thread.v2/0?context=%7b%22Tid%22%3a%2268 c00060-d80e-40a5-b83f- 3b8a5bc570b5%22%2c%22Oid%22%3a%229d684c1d-4eb2-40d0- a319- 8a0562477992%22%2c%22IsBroadcastMeeting%22%3atrue%7d 1 Apologies for absence and attendance roll call. -

Peel Land & Property Environmental Ltd LOCATION: Port Salford Way

APPLICATION No: 20/75027/FUL APPLICANT: Peel Land & Property Environmental Ltd LOCATION: Port Salford Way, Eccles, PROPOSAL: Construction and operation of a temporary recycled aggregate facility comprising waste soil and mineral wash plant, temporary access road and ancillary plant and infrastructure WARD: Irlam Description of Site and Surrounding Area The application relates to an irregularly shaped parcel of scrubland extending approximately 3.9ha to the south of the A57 Liverpool Road within the Strategic Regional Site of Port Salford. The site is screened to the north, north-east and western aspects by an established landscaped buffer and public footpath (PROW 2) delineating the main carriageway of the A57. Beyond the main carriageway lies City Airport and associated buildings (of which two are Grade II listed) and a pair of semi-detached properties. The south- east boundary is formed by the meandering Salteye Brook whilst the western aspect comprises the distribution facility of Great Bear and beyond, the wholesalers Makro. The AJ Bell Stadium and recently constructed Aldi Supermarket lies further east. Description of Proposal Permission is sought for the formation of a temporary recycling facility comprising an inert waste soil and mineral washing plant with associated stockpile area, new access road and ancillary plant and infrastructure. Figure 1: Proposed Site Plan In order to facilitate the proposal, the development will require: A washing plant with a throughput of c.240,000 tonnes per annum, apportioned as follows: o Recycling aggregates – c.192,000 tonnes per annum; o Cohesive Engineering fill material – c.48,000 tonnes per annum. Up to 2,900 sqm feedstock and product stockpile area for storage of materials prior to and following processing (up to a maximum height of 6.5m); Construction of temporary haul road from Port Salford Way into the site; Ancillary plant and site infrastructure comprising: o Up to two front-loading shovels; o Wheel wash facility; o Weighbridge; o Substation; o Fencing; o Car parking; and o 2no. -

This Edition Was Created on Tuesday June 4Th 2019 and Contains a List of Books and Magazines, Both Bound and Loose a List Of

This edition was created on Tuesday June 4th 2019 and contains a list of books and magazines, both bound and loose A list of new titles added since the creation of the last list can be found on the website in the 'book catalogues' tab To check availability of items please contact us either by – using the 'Contact Us' button on this website, or call +44(0)1947895170 (opening hours are shown on the website home page www.grosmontbooks.co.uk). Postage and Packing at or about cost due to Royal Mail charging structure based on weight and size of parcel. Reductions negotiable on volume purchases. Title Author Edition Publisher ISBN Comments Price Loose magazines, many issues available, send your list of requirements for us to check 04/1927 - Beyer-Peacock Quarterly Review 01/1932 British Railway Journal British Railways Magazine, North Eastern Region 50s & early 60s issues between 04/1950 & British Transport British Transport Review 08/1960 Commission published 3 times per year Cassell's Railways of the World Parts 6 – 18 Great Western Railway Journal Industrial Archaeology Industrial Railway Record Journal of the Institution of Locomotive Engineers various 1940s L&NWR Society Journal Loco Profile Profile Publications various issues 2.00 1946 Apr-Dec; 1947; 1948; 1949 Locomotive Express, practical articles by Jan-July, Sept- practical men Dec; 1950 Jan nos. 111-117; Locomotive Railway Carriage & Wagon 119-136; 669, Review 674, July 59 paper covers, most loose Locomotives Illustrated LYR Focus, the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway Society Midland