The Tide Is Coming In: Fort Pulaski's Historical Relationship with Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Structure Report: Battery Horace Hambright, Fort Pulaski National Monument, Georgia

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Fort Pulaski National Monument Georgia Battery Horace Hambright Historic Structure Report Cultural Resources, Partnerships and Science Division Battery Horace Hambright Fort Pulaski National Monument, Georgia Historic Structure Report February 2019 Prepared by: Panamerican Consultants, Inc. 2390 Clinton Street Buffalo, New York 14227 Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc. 330 Pfingsten Road Northbrook, Illinois 60062 Prepared for: National Park Service Southeast Regional Office 100 Alabama Street SW Atlanta, Georgia 30303 Cultural Resources, Partnership and Science Division Southeast Region National Park Service 100 Alabama Street, SW Atlanta, Georgia 30303 (404) 562-3117 About the front cover: View of Battery Horace Hambright from HABS GA-2158. This manuscript has been authored by Panamerican Consultants, Inc., and Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc., under Contract Number P16PD1918 with the National Park Service. The United States Government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the United States Government retains a non-exclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, worldwide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript, or allow others to do so, for United States Government purposes. Battery Horace Hambright Fort Pulaski National Monument, Georgia Historic Structure Report Contents List of Figures .................................................................................................................................................................. -

By Tilly Reynolds and Caitlin Griffith

By Tilly Reynolds and Caitlin Griffith VICTORIAN NATIONAL PARKS ASSOCIATION The Victorian National Parks Association (VNPA) helps shape the agenda for creating and managing national parks, conservation reserves and other important natural areas across land and sea in Victoria. The VNPA works with all levels of government, the scientific community and the general community to achieve long term, best practice environmental outcomes. The VNPA is also Victoria’s largest bushwalking club and provides a range of information, education and activity programs to encourage Victorians to get active for nature. REEF WATCH Reef Watch is a citizen science program run by the VNPA. The program encourages divers and snorkellers to monitor marine life at their favourite dive sites. The project has been developed by the Australian Marine Conservation Society and the Marine and Coastal Community Network. Reef Watch co-ordinates a number of marine conservation programs, including ‘Feral or in Peril’ and the Great Victorian Fish Count. In 2012 Reef Watch won the 2012 award for Excellence In Education from Victoria’s Coastal Council. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VNPA: Chris Smyth, Caitlin Griffith, Heath Rickard, John Sampson, Victoria McClellan (volunteer). Parks Victoria: Mark Rodrigue, Shannon Hurley, Stephen Tuohy, David Langmead, Jessica Strang and Pete Hay, Rob Hemsworth, Chris Hayward. Coastcare Victoria: Philip Wierzbowszki. Museum Victoria and Redmap Victoria: Mark Norman, Dianne Bray, Julian Finn, Robin Wilson. Ecologic: Sharon Blum-Caon. Participating groups: -

Amend the Senate Transportation Committe

08 AM 34 0254 ADOPTED Senator Mullis of the 53rd offered the following amendment: 1 Amend the Senate Transportation Committee substitute to HR 468 by inserting between lines 2 7 and 8 of page 12 the following: 3 WHEREAS, Christmas Moultrie was born a slave on Mulberry Grove Plantation on 4 Christmas Day, 1863; and 5 WHEREAS, Christmas Moultrie was the last child born into slavery on Mulberry Grove 6 Plantation; and 7 WHEREAS, Christmas Moultrie lived most of his life on the Plantation as a renowned 8 Savannah River market hunter; and 9 WHEREAS, Christmas Moultrie´s expertise as a market hunter is documented in a book 10 entitled Ward Allen, Savannah River Market Hunter by John Eugene Cay, Jr., copyright 11 1958; and 12 WHEREAS, Mulberry Grove Plantation was where President George Washington stayed 13 during his only visits to Georgia in the 1790´s as the guest of Catherine Greene, the widow 14 of the Revolutionary War hero, General Nathaniel Greene; and 15 WHEREAS, Christmas Moultrie´s grave is located outside Port Wentworth, Georgia, in 16 historic Cherokee Hill Cemetery; and 17 WHEREAS, it is only fitting that the life of Christmas Moultrie be memorialized by 18 dedicating an interchange in his honor. 19 PART XIX 20 WHEREAS, portions of U.S. Highways 129, 78, and 278 and State Routes 47, 77, and 22 21 pass through historically significant regions of this state, especially with regard to Georgians 22 who were leaders in the American Civil War; and 23 WHEREAS, recognizing and promoting the historical significance of this region could 24 promote economic development through tourism. -

Stratigraphical Framework for the Devonian (Old Red Sandstone) Rocks of Scotland South of a Line from Fort William to Aberdeen

Stratigraphical framework for the Devonian (Old Red Sandstone) rocks of Scotland south of a line from Fort William to Aberdeen Research Report RR/01/04 NAVIGATION HOW TO NAVIGATE THIS DOCUMENT ❑ The general pagination is designed for hard copy use and does not correspond to PDF thumbnail pagination. ❑ The main elements of the table of contents are bookmarked enabling direct links to be followed to the principal section headings and sub-headings, figures, plates and tables irrespective of which part of the document the user is viewing. ❑ In addition, the report contains links: ✤ from the principal section and sub-section headings back to the contents page, ✤ from each reference to a figure, plate or table directly to the corresponding figure, plate or table, ✤ from each figure, plate or table caption to the first place that figure, plate or table is mentioned in the text and ✤ from each page number back to the contents page. Return to contents page NATURAL ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Research Report RR/01/04 Stratigraphical framework for the Devonian (Old Red Sandstone) rocks of Scotland south of a line from Fort William to Aberdeen Michael A E Browne, Richard A Smith and Andrew M Aitken Contributors: Hugh F Barron, Steve Carroll and Mark T Dean Cover illustration Basal contact of the lowest lava flow of the Crawton Volcanic Formation overlying the Whitehouse Conglomerate Formation, Trollochy, Kincardineshire. BGS Photograph D2459. The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Ordnance Survey licence number GD 272191/2002. -

Point Nepean Forts Conser Vation Management Plan

Point Nepean Forts Conservation Management Plan POINT NEPEAN FORTS CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN Parks Victoria July 2006 This document is based on the Conservation Plans for the Point Nepean National Park Fortifications (1990) and Gun Emplacement No. 1 (1988) prepared by the Historic Buildings Branch, Ministry Of Housing and Construction, reviewed and updated for currency at the time of creation of the new and expanded Point Nepean National Park in 2005. ii CONTEXT This Conservation Management Plan (CMP) for the Point Nepean Forts is one of three Conservation Management Plans for historic heritage that have been prepared and/or reviewed to support the Point Nepean National Park and Point Nepean Quarantine Station Management Plan, as shown below: Point Nepean National Park and Point Nepean Quarantine Station Draft Management Plan Point Nepean Forts South Channel Fort Point Nepean Quarantine Conservation Conservation Station Draft Conservation Management Plan Management Plan Management Plan The Conservation Management Plan establishes the historical significance of all the fortification structures centring on the Fort Nepean complex area, as well as Eagles Nest and Fort Pearce, develops conservation policies for the sites as a whole as well as their individual features, and provides detailed strategies and works specifications aimed at the ongoing preservation of those values into the future. The Conservation Management Plan for Point Nepean Forts supports the Point Nepean National Park and Point Nepean Quarantine Station Draft Management -

Laura's Beach and Paddleout Plan

Laura’s beach and paddleout plan Need: • Pen and paper x 30 • Yarn • Bingo sheets • Boards • Wetties • Tent • Flag WELCOME to Frankston and the beautiful Port Phillip Bay. I’m Laura Alfrey and I’m a lecturer... Acknowledgment of country We are very lucky to have a formal welcome to country later but for now I’ll acknowledge that we are stood on the traditional lands of the Boon Wurrung and Bunurong people of the Kulin nation and I wish to acknowledge them as Traditional Owners. I would like to pay my respects to their Elders, past and present, and the Elders from other communities who may be here today. The land of the Boon Wurrung and Bunurong people extends from the Werribee Creek in the north to Wilson's Promontory in the east. DRAW MAP ON SAND The traditional culture of Indigenous people is characterised by strong recognition and valuing of the roles of elders and traditional customs, such as reciprocity and a shared vision of community. At the heart of this conference is community and we hope that this meeting today is the start of our version of the IWS community, a group of women surfers who have come together to learn from each other and harness our strengths for good. Back to the map… Surf breaks/Map Places of interest: • Melbourne • The heads of the bay (Portsea and Queenscliffe) • Out west to the Great Ocean Road and home of Bells Beach • On the Mornington Peninsula: • Westernport/facing Phillip Island - point leo, shoreham and flinders • Back beaches - Gunnamatta, Rye • In the bay - south channel fort - part of a network of fortifications protecting the narrow entrance to Port Phillip. -

Final General Management Plan, Wilderness Study, and Environmental Impact Statement June 2013

Fort Pulaski National Monument National Park Service Georgia U.S. Department of the Interior Final General Management Plan, Wilderness Study, and Environmental Impact Statement June 2013 Front cover photo credits, clockwise from top left:National Park Service; Tammy Herrell; David Libman; David Libman General Management Plan / Wilderness Study / Environmental Impact Statement Fort Pulaski National Monument Chatham County, Georgia SUMMARY President Calvin Coolidge established Fort Lighthouse and the other is known as Pulaski as a national monument by Daymark Island. Finally, in 1996, Congress proclamation on October 15, 1924, under the passed a law that removed the U.S. Army authority of section 2 of the Antiquities Act Corps of Engineers’ reserved right to deposit of 1906. The proclamation declared the dredge spoil on Cockspur Island. entire 20-acre area “comprising the site of the old fortifications which are clearly This General Management Plan / Wilderness defined by ditches and embankments” to be Study / Environmental Impact Statement a national monument. provides comprehensive guidance for perpetuating natural systems, preserving By act of Congress on June 26, 1936 (49 Stat. cultural resources, and providing 1979), the boundaries of Fort Pulaski opportunities for high-quality visitor National Monument were expanded to experiences at Fort Pulaski National include all lands on Cockspur Island, Monument. The purpose of the plan is to Georgia, then or formerly under the decide how the National Park Service can jurisdiction of the secretary of war. The best fulfill the monument’s purpose, legislation also authorized the Secretary of maintain its significance, and protect its the Interior to accept donated lands, resources unimpaired for the enjoyment of easements, and improvements on McQueens present and future generations. -

Original File Was Main.Tex

Originally published as: Kyba, C., Conrad, J., Shatwell, T. (2020): Lunar illuminated fraction is a poor proxy for moonlight exposure. - Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4, 318-319. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1096-7 Lunar illuminated fraction is a poor proxy for moonlight exposure Christopher C.M. Kyba 1,2,* , Jeff Conrad 3 , and Tom Shatwell 4 1 Deutsches GeoForschungsZentrum Potsdam, Remote Sensing & Geoinformatics, Potsdam, 14473, Germany 2 Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries, Ecohydrology, Berlin, 12587, Germany 3 No institutional affiliation, California, USA 4 Helmholtz-Zentrum für Umweltforschung—UFZ, Seenforschung, Magdeburg, 39114, Germany * [email protected] Introduction San-Jose et al. recently demonstrated that the colouration of barn owls impacts their hunting success under moonlit conditions, and therefore affects their reproductive success[1]. They found that near full moon conditions, the youngest nestlings with white fathers were fed more and were likelier to survive than those with redder fathers. While the study is interesting, the percentage of the moon that is illuminated (lunar illuminated fraction) is unfortunately a poor proxy for moonlight exposure. We suggest lunar illluminated fraction should in general never be used in biological studies, as alternative variables such as horizontal illuminance better represent moonlight exposure, and therefore offer a greater chance of detecting effects of moonlight. Here, we provide a brief explanation of how moonlight varies with season and time of night, and stress the need for greater collaboration between biologists and astronomers or physicists in such studies in the future. Due to the moon’s rotation around the Earth, it rises later each night than it did the night before. -

Priest Recalls Masses He Said at Aunt's Elba Island Home

Thursday, August 18, 2005 FEATURE Southern Cross, Page 3 Priest recalls Masses he said at aunt’s Elba Island Home he late Monsignor Thomas J. Brennan had photos taken when he ven- Ttured to Elba Island in the summer of 1924 to say Mass. The young priest recorded the date on the back of one of the photographs: June 20, 1924. Brennan also recorded dates of the second and third Masses he cele- brated at the lighthouse keeper’s home on the island on June 21 and July 3. Father Brennan’s Henry Martus, 53, retains his rank, memories of being listed as “ordinance sergeant”, these Masses while his son, George, 19 years, is said early in his identified as “assistant light keeper”. long and fruitful Martus’ wife, Rosanna, 52, is keep- career revealed ing house and daughters Rosanna J., the regard he felt 21; Mary, 14, and Florence, 12, for his Uncle “reside in the home.” Rita H. DeLorme George, keeper The demographics of the Martus of the Elba household changed considerably in Island light, and his Aunt, Flo- the decade following the 1880 cen- rence—George’s sister—who spent sus. By 1890, John Martus had died, courtesy of the Diocesan Archives. Photo most of her life on the lonely is- and the two older Martus daughters Father Thomas J. Brennan prepares for Mass on Elba Island in 1924. land. Brennan would go on to labor had married. Only the widowed those who sailed the seas came to and in turn each vessel, from the successfully in the missions of Rosanna Martus, son George, and expect her salute. -

What's Hot on the Moon Tonight?: the Ultimate Guide to Lunar Observing

What’s Hot on the Moon Tonight: The Ultimate Guide to Lunar Observing Copyright © 2015 Andrew Planck All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any written, electronic, recording, or photocopying without written permission of the publisher or author. The exception would be in the case of brief quotations embodied in the critical articles or reviews and pages where permission is specifically granted by the publisher or author. Although every precaution has been taken to verify the accuracy of the information contained herein, the publisher and author assume no responsibility for any errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for damages that may result from the use of information contained within. Books may be purchased by contacting the publisher or author through the website below: AndrewPlanck.com Cover and Interior Design: Nick Zelinger (NZ Graphics) Publisher: MoonScape Publishing, LLC Editor: John Maling (Editing By John) Manuscript Consultant: Judith Briles (The Book Shepherd) ISBN: 978-0-9908769-0-8 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2014918951 1) Science 2) Astronomy 3) Moon Dedicated to my wife, Susan and to my two daughters, Sarah and Stefanie Contents Foreword Acknowledgments How to Use this Guide Map of Major Seas Nightly Guide to Lunar Features DAYS 1 & 2 (T=79°-68° E) DAY 3 (T=59° E) Day 4 (T=45° E) Day 5 (T=24° E.) Day 6 (T=10° E) Day 7 (T=0°) Day 8 (T=12° W) Day 9 (T=21° W) Day 10 (T= 28° W) Day 11 (T=39° W) Day 12 (T=54° W) Day 13 (T=67° W) Day 14 (T=81° W) Day 15 and beyond Day 16 (T=72°) Day 17 (T=60°) FINAL THOUGHTS GLOSSARY Appendix A: Historical Notes Appendix B: Pronunciation Guide About the Author Foreword Andrew Planck first came to my attention when he submitted to Lunar Photo of the Day an image of the lunar crater Pitatus and a photo of a pie he had made. -

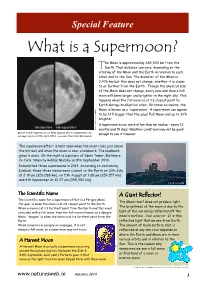

What Is a Supermoon?

Special Feature What is a Supermoon? he Moon is approximately 384,400 km from the T Earth. That distance can vary, depending on the orbiting of the Moon and the Earth in relation to each other and to the Sun. The diameter of the Moon is 3,476 km but this does not change, whether it is closer to or further from the Earth. Though the physical size of the Moon does not change, every now and then a full moon will seem larger and brighter in the night sky. This happens when the full moon is at its closest point to Earth during its elliptical orbit. On these occasions, the Moon is known as a 'supermoon'. A supermoon can appear to be 14% bigger than the usual Full Moon and up to 30% brighter. A supermoon occur more often than we realise - every 13 Photos courtesy of Robbie Murphy Robbie of courtesy Photos months and 18 days. Weather conditions may not be good Above is the Supermoon of 10th August 2014 compared to an enough to see it however. average moon of 5th April 2014 - as seen from Sherkin Island. The supermoon effect is best seen when the moon rises just above the horizon and when the moon is near a landmark. The landmark gives it scale. On the right is a picture of Spain Tower, Baltimore, Co Cork, taken by Robbie Murphy on 8th September 2014. Ireland had three supermoons in 2014. According to Astronomy Ireland, these three moons were closest to the Earth on 13th July at 2:10 am (356,088 km), on 11th August at 1:38 am (354,157 km) and 8th September at 12:27 am (355,392 km). -

Moon's Elliptical Orbit

'Supermoon' wows viewers with closest glimpse since 1948 - BBC News By Paul Rincon Science editor, BBC News website 14 November 2016 Skywatchers are enjoying the latest "supermoon", after Earth's satellite made its closest approach since 1948. The UK's best chance to see it is on Monday evening; the Moon rose at 16:43 GMT in Edinburgh and 16:44 in London. To observers, it will appear about 7% larger than normal and about 15% brighter - although the human eye is barely able to discern that difference. The Moon was closest - only 221,524 miles (356,509km) away - at 11:21 GMT. It won't be this close again until 25 November 2034. The Met Office's UK forecast suggests it will be cloudy when the supermoon is closest, although it advises people to check their local forecast for the event. As the Moon traces its orbit around the Earth, we see different proportions illuminated by the Sun. Once in each orbit, our satellite is totally illuminated - a full moon. And as the Moon orbits the Earth every 27 days or so, it travels in an elliptical or oval shape. This means that its distance from our planet is not constant but varies across a full orbit. Media caption Newsround: What is a supermoon? But within this uneven orbit there are further variations caused by the Earth's movements around the Sun. These mean that the perigee - the closest approach - and full moon are not always in sync. But occasions when the perigee and full moon coincide have become known in popular parlance as supermoons.