0465018277-Text:Strangest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For the Thrill of It: Leopold, Loeb, and the Murder That Shocked Jazz Age

For the Thrill of It Leopold, Loeb, and the Murder That Shocked Chicago Simon Baatz The problem I thus pose is…what type of man shall be bred, shall be willed, for being higher in value…. This higher type has appeared often—but as a fortunate accident, as an exception, never as something willed…. Success in individual cases is constantly encountered in the most widely different places and cultures: here we really do find a higher type that is, in relation to mankind as a whole, a kind of superman. Such fortunate accidents of great success have always been possible and will perhaps always be possible. Friedrich Nietzsche, The Antichrist, Sections 3, 4 “I’m reminded of a little article you wrote, ‘On Crime,’ or something like that, I forget the exact title. I had the pleasure of reading it a couple of months ago in the Periodical.” “My article? In the Periodical Review?” Raskolnikov asked in surprise…. Raskolnikov really hadn’t known anything about it…. “That’s right. And you maintain that the act of carrying out a crime is always accompanied by illness. Very, very original, but personally that wasn’t the part of your article that really interested me. There was a certain idea slipped in at the end, unfortunately you only hint at it, and unclearly…. In short, it contains, if you recall, a certain reference to the notion that there may be certain kinds of people in the world who can…I mean not that they are able, but that they are endowed with the right to commit all sorts of crimes and excesses, and the law, as it were, was not written for them. -

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy And

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy and Anglo-American Relations, 1939 – 1958 Submitted by: Geoffrey Charles Mallett Skinner to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, July 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Abstract There was no special governmental partnership between Britain and America during the Second World War in atomic affairs. A recalibration is required that updates and amends the existing historiography in this respect. The wartime atomic relations of those countries were cooperative at the level of science and resources, but rarely that of the state. As soon as it became apparent that fission weaponry would be the main basis of future military power, America decided to gain exclusive control over the weapon. Britain could not replicate American resources and no assistance was offered to it by its conventional ally. America then created its own, closed, nuclear system and well before the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, the event which is typically seen by historians as the explanation of the fracturing of wartime atomic relations. Immediately after 1945 there was insufficient systemic force to create change in the consistent American policy of atomic monopoly. As fusion bombs introduced a new magnitude of risk, and as the nuclear world expanded and deepened, the systemic pressures grew. -

A Singing, Dancing Universe Jon Butterworth Enjoys a Celebration of Mathematics-Led Theoretical Physics

SPRING BOOKS COMMENT under physicist and Nobel laureate William to the intensely scrutinized narrative on the discovery “may turn out to be the greatest Henry Bragg, studying small mol ecules such double helix itself, he clarifies key issues. He development in the field of molecular genet- as tartaric acid. Moving to the University points out that the infamous conflict between ics in recent years”. And, on occasion, the of Leeds, UK, in 1928, Astbury probed the Wilkins and chemist Rosalind Franklin arose scope is too broad. The tragic figure of Nikolai structure of biological fibres such as hair. His from actions of John Randall, head of the Vavilov, the great Soviet plant geneticist of the colleague Florence Bell took the first X-ray biophysics unit at King’s College London. He early twentieth century who perished in the diffraction photographs of DNA, leading to implied to Franklin that she would take over Gulag, features prominently, but I am not sure the “pile of pennies” model (W. T. Astbury Wilkins’ work on DNA, yet gave Wilkins the how relevant his research is here. Yet pulling and F. O. Bell Nature 141, 747–748; 1938). impression she would be his assistant. Wilkins such figures into the limelight is partly what Her photos, plagued by technical limitations, conceded the DNA work to Franklin, and distinguishes Williams’s book from others. were fuzzy. But in 1951, Astbury’s lab pro- PhD student Raymond Gosling became her What of those others? Franklin Portugal duced a gem, by the rarely mentioned Elwyn assistant. It was Gosling who, under Franklin’s and Jack Cohen covered much the same Beighton. -

Iasinstitute for Advanced Study

IAInsti tSute for Advanced Study Faculty and Members 2012–2013 Contents Mission and History . 2 School of Historical Studies . 4 School of Mathematics . 21 School of Natural Sciences . 45 School of Social Science . 62 Program in Interdisciplinary Studies . 72 Director’s Visitors . 74 Artist-in-Residence Program . 75 Trustees and Officers of the Board and of the Corporation . 76 Administration . 78 Past Directors and Faculty . 80 Inde x . 81 Information contained herein is current as of September 24, 2012. Mission and History The Institute for Advanced Study is one of the world’s leading centers for theoretical research and intellectual inquiry. The Institute exists to encourage and support fundamental research in the sciences and human - ities—the original, often speculative thinking that produces advances in knowledge that change the way we understand the world. It provides for the mentoring of scholars by Faculty, and it offers all who work there the freedom to undertake research that will make significant contributions in any of the broad range of fields in the sciences and humanities studied at the Institute. Y R Founded in 1930 by Louis Bamberger and his sister Caroline Bamberger O Fuld, the Institute was established through the vision of founding T S Director Abraham Flexner. Past Faculty have included Albert Einstein, I H who arrived in 1933 and remained at the Institute until his death in 1955, and other distinguished scientists and scholars such as Kurt Gödel, George F. D N Kennan, Erwin Panofsky, Homer A. Thompson, John von Neumann, and A Hermann Weyl. N O Abraham Flexner was succeeded as Director in 1939 by Frank Aydelotte, I S followed by J. -

The Opening of the Atlantic World: England's

THE OPENING OF THE ATLANTIC WORLD: ENGLAND’S TRANSATLANTIC INTERESTS DURING THE REIGN OF HENRY VIII By LYDIA TOWNS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington May, 2019 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Imre Demhardt, Supervising Professor John Garrigus Kathryne Beebe Alan Gallay ABSTRACT THE OPENING OF THE ATLANTIC WORLD: ENGLAND’S TRANSATLANTIC INTERESTS DURING THE REIGN OF HENRY VIII Lydia Towns, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2019 Supervising Professor: Imre Demhardt This dissertation explores the birth of the English Atlantic by looking at English activities and discussions of the Atlantic world from roughly 1481-1560. Rather than being disinterested in exploration during the reign of Henry VIII, this dissertation proves that the English were aware of what was happening in the Atlantic world through the transnational flow of information, imagined the potentials of the New World for both trade and colonization, and actively participated in the opening of transatlantic trade through transnational networks. To do this, the entirety of the Atlantic, all four continents, are considered and the English activity there analyzed. This dissertation uses a variety of methods, examining cartographic and literary interpretations and representations of the New World, familial ties, merchant networks, voyages of exploration and political and diplomatic material to explore my subject across the social strata of England, giving equal weight to common merchants’ and scholars’ perceptions of the Atlantic as I do to Henry VIII’s court. Through these varied methods, this dissertation proves that the creation of the British Atlantic was not state sponsored, like the Spanish Atlantic, but a transnational space inhabited and expanded by merchants, adventurers and the scholars who created imagined spaces for the English. -

Notices of the American Mathematical Society

• ISSN 0002-9920 March 2003 Volume 50, Number 3 Disks That Are Double Spiral Staircases page 327 The RieITlann Hypothesis page 341 San Francisco Meeting page 423 Primitive curve painting (see page 356) Education is no longer just about classrooms and labs. With the growing diversity and complexity of educational programs, you need a software system that lets you efficiently deliver effective learning tools to literally, the world. Maple® now offers you a choice to address the reality of today's mathematics education. Maple® 8 - the standard Perfect for students in mathematics, sciences, and engineering. Maple® 8 offers all the power, flexibility, and resources your technical students need to manage even the most complex mathematical concepts. MapleNET™ -- online education ,.u A complete standards-based solution for authoring, nv3a~ _r.~ .::..,-;.-:.- delivering, and managing interactive learning modules \~.:...br *'r¥'''' S\l!t"AaITI(!\pU;; ,"", <If through browsers. Derived from the legendary Maple® .Att~~ .. <:t~~::,/, engine, MapleNefM is the only comprehensive solution "f'I!hlislJer~l!'Ct"\ :5 -~~~~~:--r---, for distance education in mathematics. Give your institution and your students cornpetitive edge. For a FREE 3D-day Maple® 8 Trial CD for Windows®, or to register for a FREE MapleNefM Online Seminar call 1/800 R67.6583 or e-mail [email protected]. ADVANCING MATHEMATICS WWW.MAPLESOFT.COM I [email protected]\I I WWW.MAPLEAPPS.COM I NORTH AMERICAN SALES 1/800 267. 6583 © 2003 Woter1oo Ma')Ir~ Inc Maple IS (J y<?glsterc() crademork of Woterloo Maple he Mar)leNet so troc1ema'k of Woter1oc' fV'lop'e Inr PII other trcde,nork$ (ye property o~ their respective ('wners Generic Polynomials Constructive Aspects of the Inverse Galois Problem Christian U. -

Suttree-Pdfdrive.Com-1-1.Pdf

Praise for CORMAC McCARTHY “McCarthy is a writer to be read, to be admired, and quite honestly—envied.” —Ralph Ellison “McCarthy is a born narrator, and his writing has, line by line, the stab of actuality. He is here to stay.” —Robert Penn Warren “Mr. McCarthy has the best kind of Southern style, one that fuses risky eloquence, intricate rhythms and dead-to-rights accuracy.” —The New York Times “Cormac McCarthy is a Southerner, a born storyteller, a writer of natural, impeccable dialogue, a literary child of Faulkner … capable of black, reasonable comedy at the heart of his tragedy.” —New Republic “[McCarthy’s] lyrical prose never sacrices necessary economies [and his] sense of the tragic is almost unerring.” —Times Literary Supplement (London) The author wishes to express his gratitude to The American Academy of Arts and Letters, The Rockefeller Foundation, and The John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Dear friend now in the dusty clockless hours of the town when the streets lie black and steaming in the wake of the watertrucks and now when the drunk and the homeless have washed up in the lee of walls in alleys or abandoned lots and cats go forth highshouldered and lean in the grim perimeters about, now in these sootblacked brick or cobbled corridors where lightwire shadows make a gothic harp of cellar doors no soul shall walk save you. Old stone walls unplumbed by weathers, lodged in their striae fossil bones, limestone scarabs rucked in the oor of this once inland sea. Thin dark trees through yon iron palings where the dead keep their own small metropolis. -

To Propose Master Recreation Plan

Governor, Legislature read Spartan fans the riot act However MSU nybrook" at Michigan State 2,500 teet of a "tatl' 10ilege or knows a girl who noted after L,m"mg pohce reported few , Umver"lty, Gov John Engler umver"lty Peoplp convicted MSU's laos last year m the an eots after thiS week'" bao- kpthal1l1amp students celebrdte "'I;;"'\.-': :,,&,~:~~,v;, ;:.:: ., ::::!::::: f:,~n h..,,,, ..h,,,,,,,,,t f..,."",.,11 ~tqt<' 1\!C'AA hA"kpthllll tournament • banish noters from Lampus campuoco for up to two year., ~She'o an IdIOt," oald Wilde Scott Taubltz, a St Clalf responsIbly The law could havE' been Opponents of the law Cite ThiS year, campus celebratIOns Shores .ophomore, fears the B Brad U dber used had notmg occurred fol. First Amendment nghts to have cooled LOnsequenGeb should MSU S~ff Writer" 9 lowmg ,Stat",'s victory m freedom of a'lSOClatlOn "People are stili hangmg become known as a breedmg Monday. natIOnal champl' "First Amendment? RlOtmg out," .ald Wilde "They're hav. ground for drunken anarchists Local college students sup' onshlp basketball game IS Illegal," countered Mehosa mg 'beerbeques,' but I haven't "I'm WOl fled aboutjeopardlz- port state efforts to dropkick The meabure target!> anyone Wilde, an MSU ..ophomore heard any rumors about not- mg my future," said Taubltz, campus hoohgans rlOtmg, IllGltmg a not or journahom student from mg, knock on wood " Prompted by laot year's don. assembhng unlawfully Within Grob"e Pomte Park Wilde Wilde's Wish came true East See SPARTANS, page SA Parcells N'hood Club to stage to propose master WEEK AHEAD 'Joseph' Thursday, April 6 Tickets are now on sale recreation plan for the AprU 13 Uld 14 The Grosse Pomte News & By Bonnie Caprara tnct's lugh schools had 2,520 performUlCft of Parcen. -

British Library Courses Study Day: Exploring Diaries, 1660-2019

British Library Courses www.bl.uk/courses Study Day: Exploring Diaries, 1660-2019 Dates Sunday 24 March 2019 Times 9.45 – 16:00 Location Knowledge Centre Level All levels Cost £55 Overview Six expert speakers discuss the origins and development of diary-keeping from Samuel Pepys to 21st- century vloggers, by way of Romantic travellers, Antarctic explorers and office workers. We also discover how the British Library acquires, preserves and curates diaries, making these unique works available to the public. Programme Registration from 9.30am Tea, coffee and biscuits from 9.45am Morning session 10am – 12.30pm Welcome and Introduction - Dr Emma McEvoy, University of Westminster Kate Loveman, University of Leicester Early Modern Diaries: Samuel Pepys and his friends Emma McEvoy, University of Westminster Touring Britain: Travel Journals 1780-1830 Laura Walker, British Library Cultivating gardens to crossing the ice: Collecting and curating diaries at the British Library Panel Q&A 1 12.30pm – 1.30pm LUNCH BREAK (lunch not provided) Afternoon session 1.30pm – 4pm Graham Farmelo, University of Cambridge Using diaries in writing scientific biographies Joe Moran, Liverpool John Moores University 20th-century diaries and the history of the everyday Clare Brant, King’s College London Diaries in the digital age Panel Q&A Tea and coffee 4pm Event ends Speakers Morning Kate Loveman is an Associate Professor in English 1600-1789 at the University of Leicester, working on the history of reading, sociability and information exchange. She is an expert on Samuel Pepys and recently edited a new annotated selection of his Diary (Everyman 2018). Her other publications include Samuel Pepys and his Books: Reading, Newsgathering, and Sociability 1660–1703 (2015), Reading Fictions 1660-1740: Deception in English Literary and Political Culture (2008) and work on the introduction of chocolate into England in the seventeenth century. -

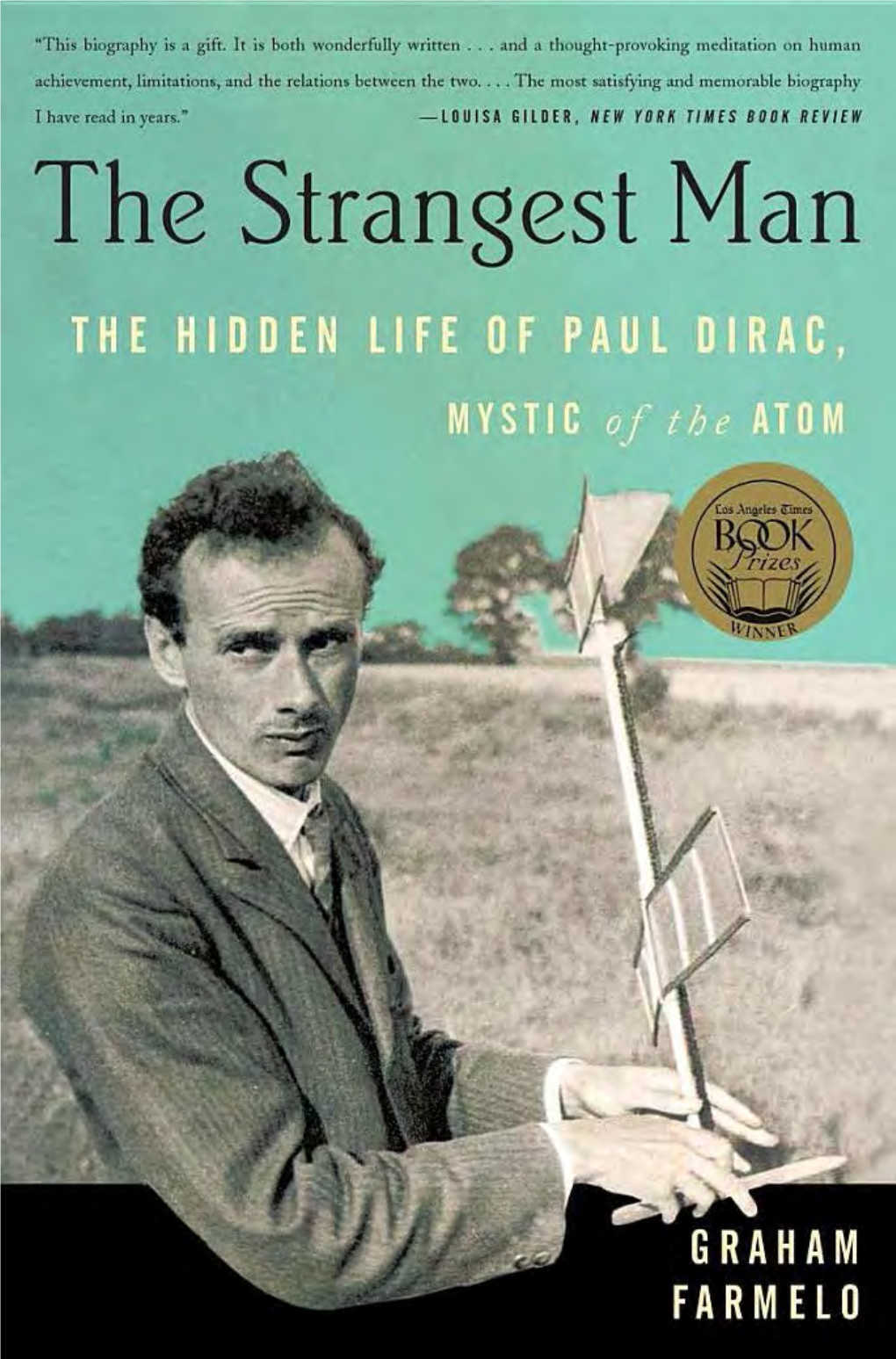

Graham Farmelo: CV in Brief

Graham Farmelo: CV in brief Fellow of Churchill College, University of Cambridge E: [email protected], T: 07973 894926 2003–2018 Author and international consultant in public engagement • Author ‘The Universe Speaks in Numbers,’ to be published in UK and USA in May 2019 • Elected Fellow of Churchill College, University of Cambridge (2017) • Director’s visitor at the IAS, Princeton, every summer 2004-2018 • Chair, CERN History Forum’s on public dimensions of history, CERN, 1 February 2018 • Led series of art-science events involving Institute of Physics and national arts institutions: Royal Opera House (2014), Royal Shakespeare Company (2015) and Tate Modern (2015) • Organised public discussion between novelist Ian McEwan and physicists Nima Arkani-Hamed about the relationship between art and science – opening of ‘Collider’ exhibition at the Science Museum, 13 November 2014 • Writer-in-residence Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics, University of California at Santa Barbara (2015) and at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics (2016) • Speaker at Blue Plaque event for Patrick Blackett’s residence in Chelsea, London, 10 April 2015 • Published ‘Churchill’s Bomb’ in US, Canada and UK (2013) • Awarded 2012 Kelvin Prize and Medal by the UK Institute of Physics • Chair, two International Panels for the Irish Government to review public provision for science communication and education in (2012, 2008) • Elected Honorary Fellow, British Science Association (2011) • Author of ‘The Strangest Man’, a biography of Paul Dirac (2009): winner, UK Costa Prize for Biography (2010), the Los Angeles Times Science Book Prize (2010); finalist for 2010 PEN biography in biography (New York); Physics World’s book of the 2009, one of Nature’s books of the year. -

Extraction: Art on the Edge of the Abyss

EXTRACTION ART ON THE EDGE OF THE ABYSS Preview of a Glorious Ruckus Michael Traynor Earth Day ❧ april 22, 2021 “Tap ‘er light.” Dedicated to the memory of Edwin Dobb. Michael Traynor, Senior Counsel at Cobalt LLP in Berkeley, California, is an honorary life trustee of Earthjustice and a member of its Council, a member of the Leadership Council of the Environmental Law Institute, an honorary life trustee of the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights under Law, President Emeritus of the American Law Institute, a Fellow of the Ameri- can Academy of Arts & Sciences, and a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. He acknowledges with appreciation the many generous and helpful suggestions from friends and family. The views stated are personal. A compilation of references selected from the growing litera- ture accompanies this preview. Jetsonorama, I Am the Change, installation, photograph by Ben Knight Copyright © 2018 and 2021 by Michael Traynor. INTRODUCTION Layout and design by Samuel Pelts & Peter Koch. At this critical time of climate disruption and unsustainable extraction of natural For noncommercial purposes, you may copy, redistribute, resources, Peter Koch,¹ a printer, publisher and fine artist, has conceived of quote from, and adapt this preview and compilation pursuant Extraction: Art on the Edge of the Abyss (www.extractionart.org).² He, and the late Ed- to Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 Inter- win Dobb,³ a writer and teacher of environmental stories, and a growing group national License (CC BY-NC 4.0), https://creativecommons. of allies, launched this inspiring project in 2018. They created “a multi-layered, org/licenses/by/4.0/. -

The Eagle 2011

Eagle_cvr_spine:Layout 1 24/11/2011 10:02 Page 1 The Eagle 2011 Printed on sustainable and 40% recycled material recycled 40% and sustainable on Printed VOLUME 93 FOR MEMBERS OF ST JOHN’S COLLEGE The Eagle 2011 ST JOHN’S COLLEGE UN I V E R S I T Y OF CA M B RI D G E 725292 01284 Design. Cameron by Designed ST JOHN’S COLLEGE U N I V E R S I T Y O F C A M B R I D GE The Eagle 2011 Volume 93 ST JOHN’S COLLEGE U N I V E R S I T Y O F C A MB R I D G E THE EAGLE Published in the United Kingdom in 2011 by St John’s College, Cambridge St John’s College Cambridge CB2 1TP www.joh.cam.ac.uk Telephone: 01223 338700 Fax: 01223 338727 Email: [email protected] Registered charity number 1137428 First published in the United Kingdom in 1858 by St John’s College, Cambridge Designed and produced by Cameron Design: 01284 725292; www.cameronacademic.co.uk Printed by Reflex Litho Limited, Thetford. Photography by Nicola Coles, Ben Ealovega, Alice Hardy, The Telegraph, John Thompson and contributors. The Eagle is published annually by St John’s College, Cambridge, and is sent free of charge to members of St John’s College and other interested parties. Items to be considered for publication should be addressed to The Editor, The Eagle, Development Office, St John’s College, Cambridge, CB2 1TP, or sent by email to [email protected].