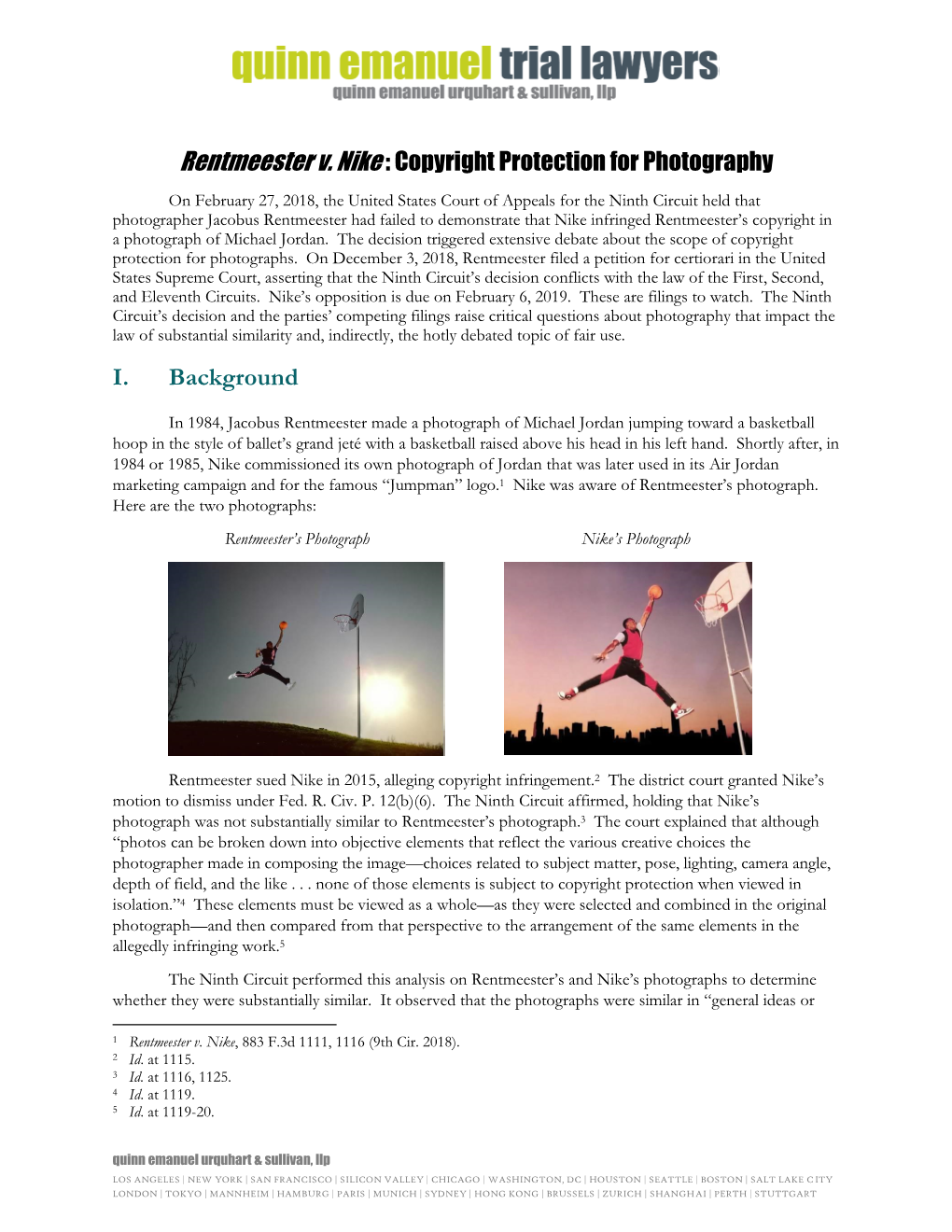

Rentmeester V. Nike : Copyright Protection for Photography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual 2018/19

1 ANNUAL 2018/19 SPORTS MARKETING, SPONSORSHIP ACTIVATION & PARTNERSHIP LEVERAGE 2 < Understand The Past Unlock The Future > We deliver creative and strategic intelligence to fuel game-changing sports and sponsorship marketing. Inspire your teams with the world’s most innovative sports brand campaigns, rights-holder marketing, sponsor activations, technologies & trends. [email protected] 3 Subscribe to Activative Sports marketing and sponsorship activation intelligence for agencies, brands, consultancies and rights-holders delivered via > Daily drop creative email > Weekly campaign newsletter > Case study database > News, deals & moves app To subscribe or book a demo email [email protected] 4 We’ve made a list and checked it (at least) twice, to bring CONTENTS you the year’s best sports and sponsorship marketing cam- 2018 Overview > paigns in the form of the ‘Activative Annual 2018/19’. P5. Trends, Themes, Strategies & Tactics After all, this is the most Activative time of the year. Throughout the last 12 months, the Activative team has 2018’s Most Activative Campaigns > looked at tens of thousands of campaigns from across the P17. Nike ‘Dream Crazy’ global sports landscape. P21. Nike ‘Nothing Beats A Londoner’ Only around 500 of these make it onto our case study P24. Nike ‘Juntas Imparables’ platform providing our subscribers (agencies, brands and P27. Jordan Brand + PSG ‘Apparel’ rights-holders) creative and strategic intelligence, insight, P30. Sasol/SAFA ‘Limitless’ and ideation to fuel their game-changing sports marketing. P33. Paddy Power ‘Rainbow Russians’ So that gives you an idea of just what it means to be show- P36. Cristal ‘The Hacking Jersey’ cased in our ‘Activative Annual’ and to make it onto our list P39. -

Nike and the Pigmentation Paradox: African American Representation in Popular Culture from ‘Sambo’ to ‘Air Jordan’

Nike and the Pigmentation Paradox: African American Representation in Popular Culture from ‘Sambo’ to ‘Air Jordan’ by Scott Warren McVittie A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Scott McVittie, May, 2016 ABSTRACT NIKE AND THE PIGMENTATION PARADOX: AFRICAN AMERICAN REPRESENTATION IN POPULAR CULTURE FROM ‘SAMBO’ TO ‘AIR JORDAN’ Scott McVittie Advisor: University of Guelph Professor Susan Nance Martin Luther King Jr. once remarked: “The economic highway to power has few entry lanes for Negroes.” This thesis investigates this limited-access highway in the context of American culture by analyzing the merger of sports celebrity branding and racial liberalism through a case study of Nike and the Air Jordan brand. As a spokesman for Nike, Michael Jordan was understood as both a symbol of “racial transcendence” and a figure of “racial displacement.” This dual identity spurred an important sociological debate concerning institutional racism in American society by unveiling the paradoxical narrative that governed discourse about black celebrities and, particularly, black athletes. Making use of archival research from the University of Oregon’s Special Collections Department, this study sheds light on the “Nike perspective” in furnishing an athletic meritocracy within a racially integrated community of consumers. Positioning this study within the field of African American cultural history, this thesis also interrogates representations -

If the Ip Fits, Wear It: Ip Protection for Footwear--A U.S

IF THE IP FITS, WEAR IT: IP PROTECTION FOR FOOTWEAR--A U.S. PERSPECTIVE Jonathan Hyman , Charlene Azema , Loni Morrow | The Trademark Reporter Document Details All Citations: 108 Trademark Rep. 645 Search Details Jurisdiction: National Delivery Details Date: November 5, 2018 at 1:16 AM Delivered By: kiip kiip Client ID: KIIPLIB Status Icons: © 2018 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. IF THE IP FITS, WEAR IT: IP PROTECTION FOR..., 108 Trademark Rep. 645 108 Trademark Rep. 645 The Trademark Reporter May-June, 2018 Article Jonathan Hyman aa1 Charlene Azema aaa1 Loni Morrow aaaa1 Copyright © 2018 by the International Trademark Association; Jonathan Hyman, Charlene Azema, Loni Morrow IF THE IP FITS, WEAR IT: IP PROTECTION FOR FOOTWEAR-- A U.S. PERSPECTIVE a1 Table of Contents I. Introduction 647 A. Why IP Is Important in the Shoe Industry 648 B. Examples of Footwear Enforcement Efforts 650 II. What Types of IP Rights Are Available 658 A. Trademarks and Trade Dress 658 1. Trademarks for Footwear 658 2. Key Traits of Trademark Protection 659 3. Remedies Available Against Infringers 660 4. Duration of Protection 661 5. Trade Dress as a Category of Trademarks 662 a. Securing Trade Dress Protection 672 6. Summary of the Benefits and Limitations of Trademarks as an IP Right 680 B. Copyrights 680 1. Copyrights for Footwear 680 2. Key Traits of Copyright Protection 689 3. Duration of Protection and Copyright Ownership 691 4. Remedies Available Against Infringers 692 5. Summary of the Benefits and Limitations of Copyrights as an IP Right 693 C. -

Jumpman Download Free

Jumpman download free Jumpman. Artist: Drake & Future. MB · Jumpman. Artist: Rick Ross. MB · Jumpman. Artist: Lil Wayne. Jumpman. Drake & Future • MB • K plays. Jumpman. Drake & Future • MB • K plays Jumpman. Drake And Future • MB • K plays. Watch the video, get the download or listen to Drake & Future – Jumpman for free. Jumpman appears on the album Young Rich Future Wap. Discover more. drake ft future 3 - Search and Download for your favorite songs in our MP3 database for free. Up next. How to: Download "Jumpman" & "Back to Back" for Free - Duration: Zack Creator 14 1. Jumpman, free and safe download. Jumpman latest version: He's a man, and he jumps. Little known fact - Jumpman was Mario's original title! This indie game is. Drake ft Future – Jump Man. Artist: Drake ft Future, Song: Jump Man, Duration: , Size: MB, Bitrate: kbit/sec, Type: mp3. № Offering action in a world of platform, Jumpman is an abandonware developed by Epyx, Inc. and published by IBM. Released in , you wander around in a. Retro 2D platformers may be a dime a dozen these days, but that makes it even harder for one of the blocky jump, shoot, and run games to rise. Listen to Jumpman by Drake, Future on Slacker Radio stations, including Drake: The Download the free Slacker Radio app and listen as long as you like. Download Drake & Future Jumpman - Lyric apk and all version history for Android. Drake & Future - Jumpman. Stream Jumpman -Drake & Future (Nonfiction Remix)FREE DOWNLOAD** by DJNonfiction from desktop or your mobile device. Jumpman free. Download fast the latest version of Jumpman: This game is one of the first game of platforms. -

Racism in the Ron Artest Fight

UCLA UCLA Entertainment Law Review Title Flagrant Foul: Racism in "The Ron Artest Fight" Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4zr6d8wt Journal UCLA Entertainment Law Review, 13(1) ISSN 1073-2896 Author Williams, Jeffrey A. Publication Date 2005 DOI 10.5070/LR8131027082 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Flagrant Foul: Racism in "The Ron Artest Fight" by Jeffrey A. Williams* "There's a reason. But I don't think anybody ought to be surprised, folks. I really don't think anybody ought to be surprised. This is the hip-hop culture on parade. This is gang behavior on parade minus the guns. That's what the culture of the NBA has become." - Rush Limbaugh1 "Do you really want to go there? Do I have to? .... I think it's fair to say that the NBA was the first sport that was widely viewed as a black sport. And whatever the numbers ultimately are for the other sports, the NBA will always be treated a certain way because of that. Our players are so visible that if they have Afros or cornrows or tattoos- white or black-our consumers pick it up. So, I think there are al- ways some elements of race involved that affect judgments about the NBA." - NBA Commissioner David Stern2 * B.A. in History & Religion, Columbia University, 2002, J.D., Columbia Law School, 2005. The author is currently an associate in the Manhattan office of Milbank Tweed Hadley & McCloy. The views reflected herein are entirely those of the author alone. -

A Case Study of Brand Associations for Yeezy Brand Garrett Kalel Grant Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 5-3-2018 A Case Study of Brand Associations for Yeezy Brand Garrett Kalel Grant Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Fashion Business Commons Recommended Citation Grant, Garrett Kalel, "A Case Study of Brand Associations for Yeezy Brand" (2018). LSU Master's Theses. 4716. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4716 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CASE STUDY OF BRAND ASSOCIATIONS FOR YEEZY BRAND A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Science in The Department of Textiles, Apparel Design, and Merchandising by Garrett Kalel Grant B.S., Tuskegee University, 2014 August 2018 This thesis is dedicated to my grandfather, A. Grant Sr. You always believed in me and everything I set out to do. I would not be at this very point in my life without your 26 years of guidance in it. I hope that this work acts as a reflection of the lessons, morals, and values you instilled in me over the years. I love you Granddaddy! (R.I.P. Arthur Grant Sr. 3.27.27-11.23.17) ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to first begin by extending my gratitude to the entire department of Textiles, Apparel Design, and Merchandising for accepting me into this program at Louisiana State University. -

Jumpman-FINAL

Rentmeester v. Nike, Inc. – “Jumpman” may be falling down to Earth After waiting almost thirty years, a photographer now claims he is the true owner of the Air Jordan logo By Rebecca Bellow and Trevor K. Roberts * This article first appeared in Inside Counsel Magazine on April 29, 2015: http://bitly.com/1EofIst In 1984, Nike signed an NBA rookie named Michael Jeffrey Jordan to a then record $2.5 million shoe endorsement deal. Included in the agreement was a clause that allowed Nike to opt out of the contract if the young player did not make the All-Star Game within his first three years in the NBA – or if the shoes did not earn at least $3 million. As it turned out, such concerns were laughable. Jordan was voted onto the All-Star team his very first year in the NBA, the first of 14 such appearances, and he then went on to win the NBA Rookie of the Year and an Olympic gold medal while playing for the U.S. Men’s Basketball Team in 1984. And the shoes? Well, the first generation Air Jordan generated a bit more than the $3 million in revenue for which Nike had hoped – about $100 million more! It was not until Michael Jordan’s third year in the NBA, however, that his statistics, and Air Jordan shoe sales, really took flight. It was in the 1986-87 season that Jordan scored over 3,000 points and averaged 37.1 points per game. He became the first player in NBA history to record 200 steals and 100 blocks in a single season. -

Trigger Happy: Videogames and the Entertainment Revolution

Free your purchased eBook form adhesion DRM*! * DRM = Digtal Rights Management Trigger Happy VIDEOGAMES AND THE ENTERTAINMENT REVOLUTION by Steven Poole Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS............................................ 8 1 RESISTANCE IS FUTILE ......................................10 Our virtual history....................................................10 Pixel generation .......................................................13 Meme machines .......................................................18 The shock of the new ...............................................28 2 THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES ....................................35 Beginnings ...............................................................35 Art types...................................................................45 Happiness is a warm gun .........................................46 In my mind and in my car ........................................51 Might as well jump ..................................................56 Sometimes you kick.................................................61 Heaven in here .........................................................66 Two tribes ................................................................69 Running up that hill .................................................72 It’s a kind of magic ..................................................75 We can work it out...................................................79 Family fortunes ........................................................82 3 UNREAL CITIES ....................................................85 -

Title Page-1

More Than a Man, Becoming a God; The Rhetorical Evolution of Michael Jordan By Patrick B. Corcoran A Senior Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of Communication of Boston College May 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE From North Carolina, at Guard, 6’6”, Michael Jordan…..………………………....1 CHAPTER TWO Past Scholarship Dealing with Athletics and Advertising…...……………………....4 The Power of Celebrity……………………………………………………………..4 Spike Lee’s Place in the Jordan Conversation…………………………………..…5 Sport as a Narrative………………………………………………………………..7 The Influence of Sports Advertisements and Their Use of Symbols…………….…10 Taking Flight with an Analysis of Air Jordan Commercials……………………...13 CHAPTER THREE Enter a Mortal, Leave a God; Michael Jordan’s Marketing Transformation……………………………………...16 A Star is Born……………………………………………………………………...16 Jordan’s Relationship with Nike Through the Years……………………………...16 Molding a Global Icon……………………………………………………...……..18 Yo! Jordan’s “Main Man,” Spike Lee…………………………………………….19 Redefining a Legend…………………………………….……………………….. 22 To Them, It’s All About the Shoes…………………………………………………24 The Architects of Jordan’s Current Image; His Commercials…………………....25 1987-1990………………………………………………………………………....25 1999-2008………………………………………………………………………....26 CHAPTER FOUR - The Early Years Spike and Mike as a Narrative Duo………………………………………….……...28 The Story of Mars and His “Main Man Money.”…………………………………32 Forging the Desire to “Be Like Mike”..……….………………………..………...46 CHAPTER FIVE - The Middle Years Fanning the Flame: Jordan’s Transition from Superman to -

NIKE, Inc . (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(D) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED May 31, 2015 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(D) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM TO . Commission File No. 1-10635 NIKE, Inc . (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) OREGON 93-0584541 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation) (IRS Employer Identification No.) One Bowerman Drive, Beaverton, Oregon 97005-6453 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (503) 671-6453 (Registrant’s Telephone Number, Including Area Code) SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(B) OF THE ACT: Class B Common Stock New York Stock Exchange (Title of Each Class) (Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered) SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(G) OF THE ACT: NONE Indicate by check mark: YES NO • if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. • if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. • whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Xacq -- New Jordans 2017 Release

xacq - new jordans 2017 Release Source: Herbert Baglione ; ; ; [Chinese shoes Network - shoe stock] HKEx latest information, Olympic sports (01968) main shareholder Wing Sound Development in June 13, 2014, the venue of the holdings of 200 million shares of the company long position at a cost of 4.222 million Hong Kong dollars, the average transaction price 2.111 Hong Kong dollars, the highest closing price of 2.14 Hong Kong dollars. After the change holdings 8.93804246 million shares, accounting for 42.6% stake. (Chinese shoes Network - the most authoritative and most professional shoe News Media Partners: shoe ; clothing and shoes information.) like a long time, we hope for a long time, STAYREAL x Reebok joint shoes off the dream has finally arrived. From early October to continue to release relevant joint message ; STAYREAL x Reebok Pump Fury shoes contained grown up after 20, the shoes still look to now seems avant-garde Reebok Pump Fury shoes, celebrating 20 set the trend still sit tight top popular chief position, and popular brand STAYREAL strong launch joint shoes! The JUKSY collect many popular celebrities wearing outfit STAYREAL x Reebok shoes fantasy picture, so that we start to wear after the ride as a reference, you may wish to read on. Recently, the New York fashion store KITH issued its 2015 name ; Pinnacle Program clothing line catalog. Will be held on the 9th of this month the sale of product lines determined in a minimalist style building, which was added without edging and loose design elements, releasing sweater, long-sleeved T-shirt, MA-1 jacket, horse cap and other products, through black ash, etc. -

2019 Annual Report and Notice of Annual Meeting 1 a WINNING LONG-TERM STRATEGY

TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter to our Shareholders 1 Notice of Annual Meeting 9 Form 10-K 65 JULY 23, 2019 TO OUR SHAREHOLDERS, This past March, I traveled to Paris to join Nike athletes and teammates for an unforgettable moment leading up to the summer’s World Cup. Together, with more than two dozen of the world’s best female footballers and other athletes, we unveiled 14 national team kits — a tournament record for Nike. As the lights came up on the incredible assembly of athletes, it was clear to me that the impact of the moment would be felt far beyond the tournament. This was an opportunity to create generational change — to bring more energy and participation to all women’s sports. That same day, we announced new grassroots partnerships that will expand opportunities for girls through sport for years to come. And powerful new chapters of our “Dream Crazy” campaign invited millions across the globe to join us in honoring the trailblazers of women’s sport — past, present and future. All of this captured a simple truth: FY19 was a year that moved Nike closer than ever before to our ultimate mission, to bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete* in the world. Alex Morgan and Megan Rapinoe, who led an unwavering U.S. Women’s National Team to one of the most-watched Women’s World Cup finals in history, were not alone in their triumphs in FY19. Shining moments across the Nike roster of athletes made this a year to behold. Eliud Kipchoge shattered the marathon world record.