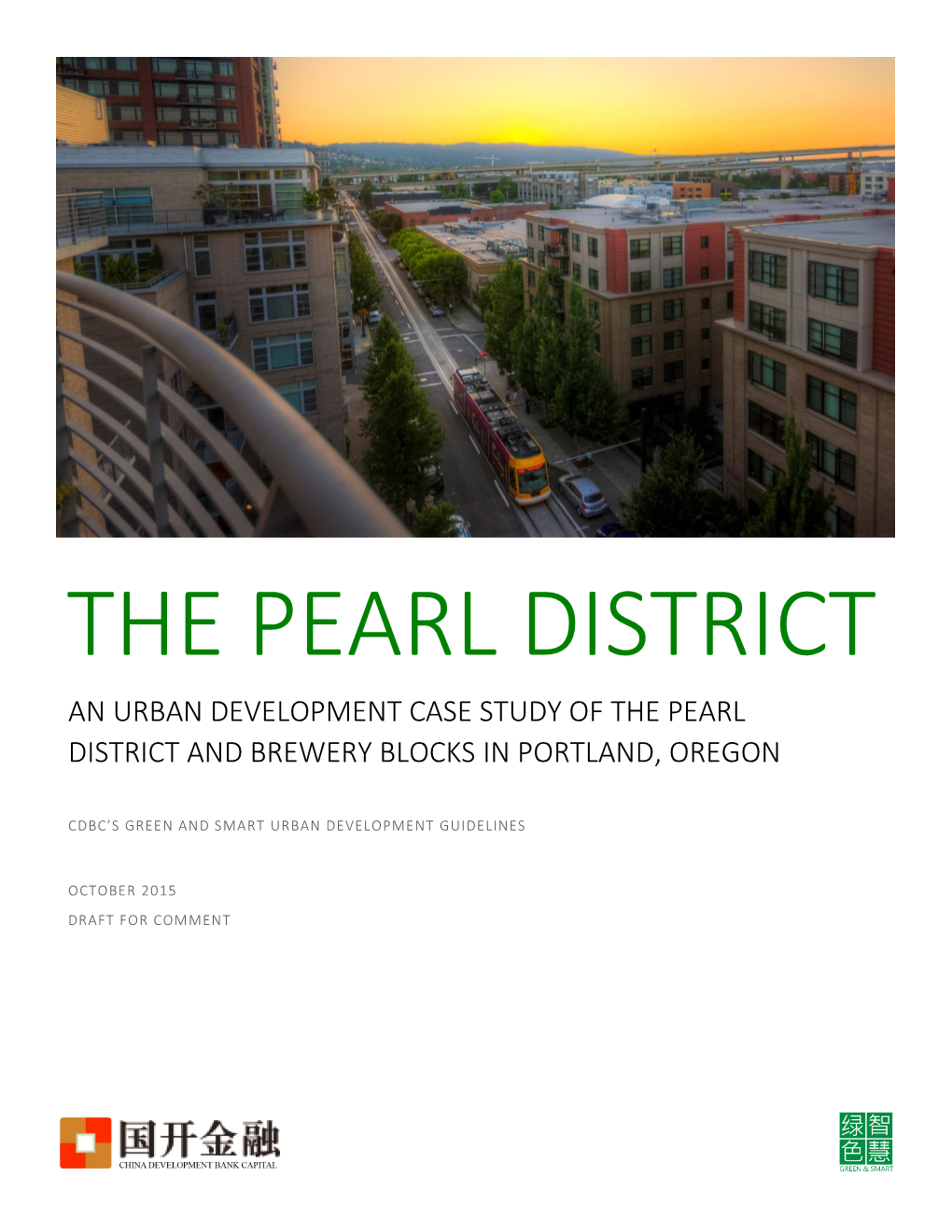

The Pearl District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Union Station Conceptual Engineering Study

Portland Union Station Multimodal Conceptual Engineering Study Submitted to Portland Bureau of Transportation by IBI Group with LTK Engineering June 2009 This study is partially funded by the US Department of Transportation, Federal Transit Administration. IBI GROUP PORtlAND UNION STATION MultIMODAL CONceptuAL ENGINeeRING StuDY IBI Group is a multi-disciplinary consulting organization offering services in four areas of practice: Urban Land, Facilities, Transportation and Systems. We provide services from offices located strategically across the United States, Canada, Europe, the Middle East and Asia. JUNE 2009 www.ibigroup.com ii Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................... ES-1 Chapter 1: Introduction .....................................................................................1 Introduction 1 Study Purpose 2 Previous Planning Efforts 2 Study Participants 2 Study Methodology 4 Chapter 2: Existing Conditions .........................................................................6 History and Character 6 Uses and Layout 7 Physical Conditions 9 Neighborhood 10 Transportation Conditions 14 Street Classification 24 Chapter 3: Future Transportation Conditions .................................................25 Introduction 25 Intercity Rail Requirements 26 Freight Railroad Requirements 28 Future Track Utilization at Portland Union Station 29 Terminal Capacity Requirements 31 Penetration of Local Transit into Union Station 37 Transit on Union Station Tracks -

WORKING DOCDRAFT Charter Directors Handbook .Docx

PPS Resource Guide A guide for new arrivals to Portland and the Pacific Northwest PPS Resource Guide PPS Resource Guide Portland Public Schools recognizes the diversity and worth of all individuals and groups and their roles in society. It is the policy of the Portland Public Schools Board of Education that there will be no discrimination or harassment of individuals or groups on the grounds of age, color, creed, disability, marital status, national origin, race, religion, sex or sexual orientation in any educational programs, activities or employment. 3 PPS Resource Guide Table of Contents How to Use this Guide ....................................................................................................................6 About Portland Public Schools (letter from HR) ...............................................................................7 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................8 Cities, Counties and School Districts .............................................................................................. 10 Multnomah County .............................................................................................................................. 10 Washington County ............................................................................................................................. 10 Clackamas County ............................................................................................................................... -

(LI). Intent. It Is the Intent of the Limited Industrial District to Provide Areas For

613. Limited Industrial District (LI). Intent. It is the intent of the Limited Industrial District to provide areas for limited industrial purposes which are not significantly objectionable in terms of noise, odor, fumes, etc., to surrounding properties. The regulations which apply within this District are designed to encourage the formation and continuance of a compatible environment for uses generally classified to be light industrial in nature; protect and reserve undeveloped areas in Georgetown County which are suitable for such industries; and discourage encroachment by those residential, commercial or other uses capable of adversely affecting the basic industrial character of the District. 613.1 Permitted Uses. The following uses shall be permitted in any Limited Industrial District: 613.101 Research or experimental laboratory; 613.102 Transportation terminal facilities, such as deep or shallow water ports or airfields together with incidental operations, but excluding truck terminals; 613.103 Public utility installation; 613.104 Agricultural farm; 613.105 Horticultural nursery; 613.106 Radio and/or television station and/or transmission tower, except within restricted areas delineated in the Georgetown County Airport Master Plan; 613.107 Office building and/or office for governmental, business, professional or general purpose; 613.108 Commercial trade or vocational school; 613.109 Off-street commercial parking or storage area for customer, client or employee owned vehicles; 613.110 Lumber processing and sales; 613.111 Public buildings, -

Parks Contain and Parking and Recreation Areas

<< Chapter >> Home | TOC | Index Courtesy DeRevere and Associates The distribution and training center for Konica Business Machines in Huntington Beach, California. such as building entrances, outdoor gathering spots, • Industrial Park—Modern industrial parks contain and parking and recreation areas. large-scale manufacturing and warehouse facilities • On-site Amenities and Services—Expectations for and a limited amount of or no office space.1 on-site amenities and services for employees have • Warehouse/Distribution Park—Warehouse and dis- become higher. In addition to contributing to a more tribution parks contain large, often low-rise storage interesting and desirable working environment, ameni- facilities with provisions for truck loading and parking. ties can help distinguish a project in a competitive A small proportion of office space may be included, market. either as finished space built into the storage areas or • Flexible Building Design—Each building type found housed in separate office structures. Landscaping and at business parks has distinctive building requirements, parking areas are included, but because of the rela- but all require functionality and flexibility to meet tively low ratios of employees to building area, a wide changing market conditions and occupiers’ needs. mix of on-site amenities for employees is not available. Flexible building design starts with basic considera- • Logistics Park—Known as commerce parks in the tions such as the size and depth of floorplates and United Kingdom and Gewerbeparks in Germany, such moves into advanced technical systems that help business parks focus on the value-added services of make a building “smart.” logistics and processing rather than warehousing and • Appropriate Parking—Parking ratios are increas- storage. -

Fact Sheet 2017

FACT SHEET 2017 Mission PFM operates world-class farmers markets that contribute to the success of local food growers and producers and create vibrant community gatherings. As a trade association, success for our vendors is our primary objective. Listening and learning from vendors and shoppers produces outstanding farmers markets where vendors prosper and communities thrive. Vision Portland Farmers Market is a catalyst for the nation’s most prosperous, healthy and sustainable food system. A system where: ● Food producers thrive and expand ● All residents have access to farm fresh food ● Farmers markets build, nourish and inspire community. Portland Farmers Market - a nonprofit 501(c)6 organization operated by a small staff and numerous volunteers - is playing a central role in creating this food system and in fostering an economically, ecologically and socially sustainable community. Downtown Portland Farmers Market at Portland State University (Year-Round) Markets South Park Blocks between SW College and SW Montgomery Portland Farmers Market at Shemanski Park South Park Blocks between SW Salmon and SW Main KINK presents Portland Farmers Market at Pioneer Courthouse Square SW Broadway between SW Morrison and SW Yamhill Neighbor Lents International Farmers Market hood Lents Town Center Markets Kenton Portland Farmers Market N Denver Avenue & N McClellan Street King Portland Farmers Market NE 7th and NE Wygant Street between NE Alberta and NE Prescott Northwest Portland Farmers Market NW 19th and NW Everett Street Staff Trudy Toliver, Executive Director Amber Holland, Market Manager Kelly Merrick, Communications Manager More Info portlandfarmersmarket.org flickr.com/photos/portlandfarmersmarket/ facebook.com/portlandfarmersmarket instagram.com/portlandfarmers twitter.com/portlandfarmers 2017 SCHEDULE MARKET DATES HOURS LOCATION Portland Farmers Market Saturdays Year-Round 8:30 a.m. -

The Fields Neighborhood Park Community Questionnaire Results March-April 2007

The Fields Neighborhood Park Community Questionnaire Results March-April 2007 A Community Questionnaire was included in the initial project newsletter, which was mailed to over 4,000 addresses in the vicinity of the park site (virtually the entire neighborhood) as well as other interested parties. The newsletter was made available for pick-up at Chapman School and Friendly House and made available electronically as well. A total of 148 questionnaires were submitted, either by mail or on the web, by the April 20 deadline. The following summarizes the results. 1. The original framework plan for the River District Parks suggested three common elements that would link the parks together. Which do you feel should be included in The Fields neighborhood park? 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Boardwalk Pedestrian Gallery Aquifer 2. This park is envisioned as a “neighborhood park no answ er – over two square blocks providing more traditional spaces for neighborhood residents. Do you agree ? with this overall concept? no yes Comments Regarding Question #2 “Traditional Neighborhood Park” #1 - None (of the original “framework concepts” are important What to you mean by "traditional" As long as this park does not become filthy (ie. bad terrain, homeless) like the waterfront, I'm for it. Excellent idea. A traditional park will be a nice complement to the other two parks. I don't know if my selections were recorded above. A continuation of the boardwalk is essential to making the connection between and among the parks. The design of the buildings around the park has narrowed the feeling of openness so it is beginning to look like a private park for the residential buildings surrounding it. -

Pearl District Market Study

Portland State University PDXScholar Northwest Economic Research Center Publications and Reports Northwest Economic Research Center 12-12-2012 Pearl District Market Study Thomas Potiowsky Portland State University Scott Stewart Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/nerc_pub Part of the Growth and Development Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Potiowsky, Thomas and Stewart, Scott, "Pearl District Market Study" (2012). Northwest Economic Research Center Publications and Reports. 22. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/nerc_pub/22 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwest Economic Research Center Publications and Reports by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Pearl District Market Study Northwest Economic Research Center Portland State University PO BOX 751 Portland, OR 97207-0751 503-725-8167 www.pdx.edu/nerc Northwest Economic Research12/10/2012 Center 1 | P a g e The Pearl District Portland State University PO BOX 751 Portland, OR 97207-0751 503-725-8167 www.pdx.edu/nerc Northwest Economic Research Center College of Urban & Public Affairs Northwest Economic Research Center 2 | P a g e Acknowledgements Contribution of the Pearl District Market Study The following report was researched and written by the Northwest Economic Research Center (NERC) at the request of the USCIS. John Oliver, Vice President of Williams/Dame & Associates, Inc, and his staff were integral to the success of the project. -

Waterfront Pearl

FOR LEASE OR SALE WATERFRONT PEARL FOR LEASE OR SALE | COMMERCIAL CONDO FIELD OFFICE 300,000 SF office COMMERCIAL CONDO WATERFRONT PEARL DEMOGRAPHICS Miles 0.5 1 2 PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS Employees 16,917 88,374 179,331 Population 8,173 25,968 93,829 • Approximately 1,011 SF (Unit 106) Avg HH Income $88,644 $65,405 $74,564 Lease Rate: $22/SF NNN Asking Price: $550,000 • 1 parking space included inside garage The Abigail • Beautiful Tenant Improvements completed BLOCK 26 155 units residential opened 2016 proposed in 2016 (including grease trap) • 192 units of high-end residential Broadstone The Reveal Ramona Centennial Mills condominiums with 300 residents 147 units redevelopment proposed • HOA monthly fees include gas, water, Modera Pearl The Parker 1264 NW Naito garbage, other common area expenses 280 units 177 units opened 2014 opened 2014 ($508/month) The Fields Park Waterfront • Real Estate Taxes: $3,400 Pearl Freedom NV BLOCK 17 Center 284 units 281 units opened 2016 opened 2014 1264 NW Naito Parkway, Portland, Oregon 97209 The Tanner Cosmopolitan Point 153 units 8-story office opened 2016 opened 2018 Tanner Springs Alber’s Mill Kearney Enso Asa Flats Loft Plaza Park Place Post Office Redevelopment proposed Pearl BLOCK 136 Jamison Court 208 units Square opened 2014 CONTACT CONTACT Anne Hecht Anne Hecht Director Director 503 279 1728 503 279 1728 [email protected] [email protected] Cushman & Wakefield of Oregon, Inc. Cushman & Wakefield of Oregon, Inc. 200 SW Market Street, Suite 200 Cushman & Wakefield Copyright 2015. No warranty or representation, express or implied, is made to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained herein, and same is submitted subject to errors, omissions, change of price, rental 200 SW Market Street, Suite 200 Cushman & Wakefield Copyright 2015. -

PP Annual Report Exec Summary V4.Indd

2015–16 Dear Portlanders: Thank you for your recent commitment to repairing and improving Portland’s parks. In November 2014, you and an impressive 74 percent of Portlanders voted “Yes” for the Parks Replacement Bond Projects26 underway — the highest percentage ever for a Parks ballot measure. You became part of a long tradition of Portlanders who’ve built and maintained our city’s enviable collection of park facilities. In this fi rst full year of the Bond, from July 2015 to July 2016, we’ve laid the foundation for the work to be done. In this upcoming year, you’ll start to see tangible results in the parks. Replacement of the 70 to 90 year old mechanical systems at Grant Pool was the fi rst completed project, and next year, results will be visible across the city. Project1 completed About every nine years over the last century, Portlanders have invested in increasing, preserving and maintaining our park system by voting “yes” on parks bonds or levies. Before the 2014 bond, the last major bond was in 1994, meaning 20 years passed without signifi cant park improvements or address- ing dire repair needs. Portland Parks & Recreation anticipates a $248 million funding gap for major maintenance needs over the next 10 years. The $68 million in funds from the 2014 Parks Replacement Bond will not address all of these maintenance issues, but it is vital to fi xing, upgrading and replacing the most crucial of these needs. Projects18 ahead of As your Parks Commissioner and Parks Director, we are making sure the funds will be used wisely and schedule maximize benefi ts to the greatest number of park users. -

Panh D Uni ±

PANHANDLE PLANNED UNIT DEVELOPMENT ± 159 ACRES PREPARED FOR: COASTAL BEND PROPERTY DEVELOPMENT, LP ET AL PREPARED BY: JANUARY 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction Purpose Location and Existing Conditions Access, Utilities & Drainage II. Project Description Land Use Permitted Uses III. Development Guidelines Development Regulations Signage Phasing/Development Schedule IV. Exhibits ‘A’ - Area Map & Conceptual Development Plan ‘B’ – Exhibit Two from the 2019 City of Friendswood Master Drainage Plan (Northern Panhandle Regional Detention) ‘C’ - Permitted Use Table ‘D’ - Parking Group Table Amendments I. Introduction Purpose This application has been prepared on behalf of Coastal Bend Property Development and other applicants attached hereto pursuant to the City of Friendswood’s Ordinances related to creation of the Panhandle Planned Unit Development (PUD). The purpose of the PUD District is to encourage flexibility in the development of land, promote the most appropriate uses, and encourage a cohesive commercial, industrial, and recreational development. This PUD will establish development regulations and standards that will ensure quality development, consistent with the intent of the Friendswood Subdivision and Zoning Ordinances. Location and Existing Conditions Prior to the development of Timber Creek Golf Club (2001), the “Panhandle” region of the City of Friendswood had long been idled except for active oil & gas production and cattle grazing. A major factor in this long dormant condition was that the vast majority of the region was held in undivided interest ownerships whose primary concern was mineral interest income from the original 1937 Humble Oil & Gas leases, owned today by Denbury Resources. Aside from the long time Whitley family’s feed store and drywall business, only a few automotive, warehouse, storage and a single retail gas/convenience store existed within the City’s limits along FM 2351 with AAA Blastcoat being the only business on Beamer Rd. -

Central City 2035 Planning Team

Volume 5A IMPLEMENTATION: PERFORMANCE TARGETS AND ACTION PLANS RESOLUTION NO. 37360 Effective July 9, 2018 Bureau of Planning and Sustainability Innovation. Collaboration. Practical Solutions. City of Portland, Oregon Ted Wheeler, Mayor • Susan Anderson, Director The Bureau of Planning and Sustainability is committed to providing equal access to information and hearings. If you need special accommodation, interpretation or translation, please call 503-823-7700, the TTY at 503-823-6868 or the Oregon Relay Service at 711 within 48 hours prior to the event. La Oficina de Planificación y Sostenibilidad se compromete a proporcionar un acceso equitativo a la información y audiencias. Si necesita acomodación especial, interpretación o traducción, por favor llame al 503-823-7700, al TTY al 503-823-6868 o al Servicio de Retransmisión de Oregon al 711 dentro de las 48 horas antes del evento. 规划和可持续发展管理局致力于提供获取信息和参加听证会的平等机遇。如果您需要特殊适应性服 务、口译或翻译服务,请在活动开始前48小时内致电:503-823-7700、TTY:503-823-6868 或联系俄勒 冈州中继服务:711。 Cục Quy Hoạch và Bền Vững (The Bureau of Planning and Sustainability) cam kết đem lại quyền tiếp cận thông tin và xét xử công bằng. Nếu quý vị cần nhà ở đặc biệt, dịch vụ thông dịch hoặc phiên dịch, vui lòng gọi số 503-823-7700, dịch vụ TTY theo số 503-823-6868 hoặc Dịch Vụ Tiếp Âm Oregon theo số 711 trong vòng 48 giờ trước khi diễn ra sự kiện. Управление планирования и устойчивого развития предоставляет равный доступ к информации и к проводимым слушаниям. Если Вам требуются особые условия или устный или письменный перевод, обращайтесь по номеру 503-823-7700, по телетайпу для слабослышащих 503-823-6868 или через Орегонскую службу связи Oregon Relay по номеру 711 за 48 часов до мероприятия. -

Ballou & Wright

BALLOU & WRIGHT 1010 NW FLANDERS STREET, PORTLAND, OR 97209 New meets old in the Pearl District’s incredible Ballou & Wright building. Originally designed by Sutton & Whitney Architects, and named after an iconic regional innovator, the property was one of the finest bicycle and automobile equipment buildings in the roaring 1920s. It is one of the city’s best preserved warehouses, with its vertical tower, ornamental facades, winged wheel emblem and striking white brick. Specht Development is artfully breathing new life into this exciting space with modern, creative office space while embracing the building’s inspiring history. The mix of tradition and luxurious modern simplicity in one of the city’s most desired neighborhoods makes this a unique opportunity for a company seeking to establish or expand its presence in Portland. Corner of NW 10th and Flanders -StreetCorner View of NW 10th and Flanders -Street View 19 19 Corner of NW 10th and Flanders -Street View Main Rooftop Deck - Conceptual Rendering19 Corner of NW 10th and Flanders -StreetCorner View of NW 10th and Flanders -Street View 19 19 BallouCorner of & NW Wright 10th and Flanders -StreetBallouCorner View of & NW Wright 10th and Flanders -Street View 19 19 February 19, 2016 February 19, 2016 412 NW Couch Street, Suite 201 Nathan Sasaki Rennie Dunn Ballou & Wright BallouFebruaryCorner 19, 2016 &of WrightNW 10th and Flanders -Street View SPECHT 19 FebruaryBallou 19, 2016& Wright FebruaryBallou 19, 2016& Wright APEXREALESTATE Portland, OR 97209 Executive Director Director February