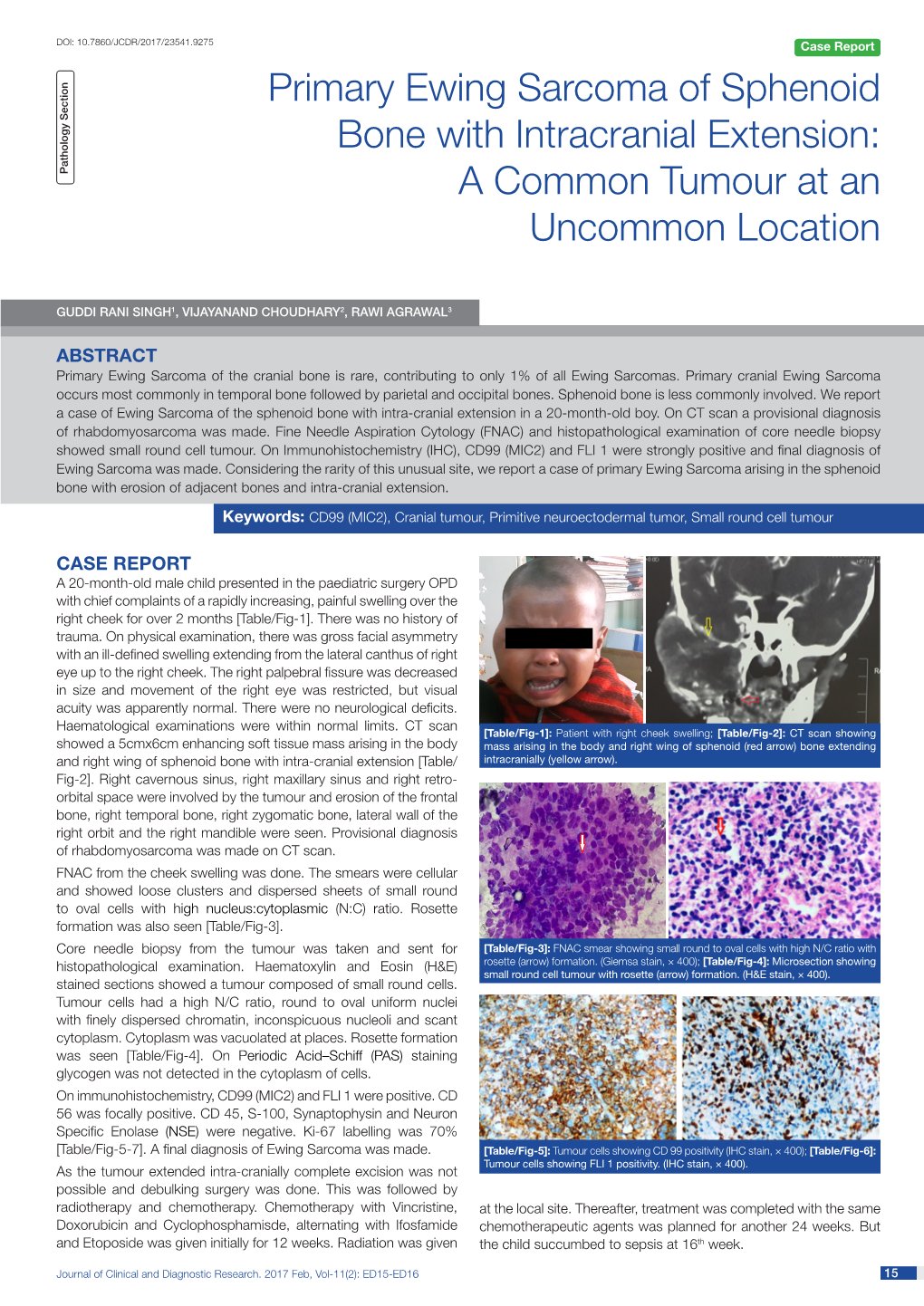

Primary Ewing Sarcoma of Sphenoid Bone with Intracranial Extension: Pathology Section a Common Tumour at an Uncommon Location

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eyelid Conjunctival Tumors

EYELID &CONJUNCTIVAL TUMORS PHOTOGRAPHIC ATLAS Dr. Olivier Galatoire Dr. Christine Levy-Gabriel Dr. Mathieu Zmuda EYELID & CONJUNCTIVAL TUMORS 4 EYELID & CONJUNCTIVAL TUMORS Dear readers, All rights of translation, adaptation, or reproduction by any means are reserved in all countries. The reproduction or representation, in whole or in part and by any means, of any of the pages published in the present book without the prior written consent of the publisher, is prohibited and illegal and would constitute an infringement. Only reproductions strictly reserved for the private use of the copier and not intended for collective use, and short analyses and quotations justified by the illustrative or scientific nature of the work in which they are incorporated, are authorized (Law of March 11, 1957 art. 40 and 41 and Criminal Code art. 425). EYELID & CONJUNCTIVAL TUMORS EYELID & CONJUNCTIVAL TUMORS 5 6 EYELID & CONJUNCTIVAL TUMORS Foreword Dr. Serge Morax I am honored to introduce this Photographic Atlas of palpebral and conjunctival tumors,which is the culmination of the close collaboration between Drs. Olivier Galatoire and Mathieu Zmuda of the A. de Rothschild Ophthalmological Foundation and Dr. Christine Levy-Gabriel of the Curie Institute. The subject is now of unquestionable importance and evidently of great interest to Ophthalmologists, whether they are orbital- palpebral specialists or not. Indeed, errors or delays in the diagnosis of tumor pathologies are relatively common and the consequences can be serious in the case of malignant tumors, especially carcinomas. Swift diagnosis and anatomopathological confirmation will lead to a treatment, discussed in multidisciplinary team meetings, ranging from surgery to radiotherapy. -

Cosmetic Lateral Canthoplasty: Lateral Topic Canthoplasty to Lengthen the Lateral Canthal Angle and Correct the Outer Tail of the Eye

Cosmetic Lateral Canthoplasty: Lateral Topic Canthoplasty to Lengthen the Lateral Canthal Angle and Correct the Outer Tail of the Eye Soo Wook Chae1, Byung Min Yun2 1BY Plastic Surgery Clinic, Seoul; 2Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Jeju National University, Jeju, Korea There are many women who want larger and brighter eyes that will give a favorable impression. Correspondence: Soo Wook Chae Surgical methods that make the eye larger and brighter include double eyelidplasty, epican- BY Plastic Surgery Clinic, Wookyung Bldg. 5th Fl., 466 Apgujeong-ro, thoplasty, as well as lateral canthoplasty. Double eyelidplasty produces changes in the vertical Gangnam-gu, Seoul 06015, Korea dimension of the eyes, whereas epicanthoplasty and lateral canthoplasty create changes in Tel: +82-2-541-5522 the horizontal dimension of the eyes. Epicanthoplasty, a surgical procedure which enlarges Fax: +82-2-545-8743 the eye horizontally, is performed at the inner corner of the eye, whereas lateral canthoplasty E-mail: [email protected] enlarges the outer edge of the eye. In particular, if the slant of the palpebral fissure is raised and the horizontal dimension of the palpebral fissure is short, adjusting the slant of the pal- pebral fissure through lateral canthoplasty can achieve an enlargement of eye width and smoother features. Depending on the patient’s condition, even better results can be achieved if this procedure is performed in conjunction with other procedures, such as double eyelid- plasty, epicanthoplasty, eye roll formation surgery, fat graft, and facial bone contouring sur- gery. In this paper, the authors will introduce in detail their surgical method for a cosmetic lateral canthoplasty that lengthens the lateral canthal angle and corrects the outer tail of the eyes, in order to ease the unfavorable impression. -

PALPEBRAL APERTURE with SPECIAL REFERENCE to the SURGICAL CORRECTION of PSEUDOPTOSIS by Rudolf Aebli, M.D.*

THE RELATIONSHIP OF PSEUDOPTOSIS TO MUSCLE TROPIAS AND THE PALPEBRAL APERTURE WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE SURGICAL CORRECTION OF PSEUDOPTOSIS BY Rudolf Aebli, M.D.* BERKE'S (1) DISSERTATION on blepharoptosis in 1945 and Spaeth's (2) on the same subject in 1946 were both so complete and so admirable in all respects that there would be no justification at this time for a duplication of their contributions. On the other hand, with the exception of Kirby's (3) paper, in 1940, on ptosis associated with loss of elevation of the eyeball, relatively little has been written on the subject of pseudoptosis caused by vertical muscle tropias. Almost nothing, furthermore, has been written on the relationship of the palpebral aperture to these anomalies. This contribution has a threefold purpose: (1) to explain this relationship; (2) to outline the correct diagnostic procedure in ptosis of the eyelid which results from anomalies of this kind; and (3) to set forth the best methods of treatment for them. ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS Before it is possible to discuss intelligently the clinical aspects of muscle tropias and the relationship of the palpebral aperture to them, certain important (albeit elementary) anatomic considera- tions must be briefly summarized. When the eyelids are in their normal relationship to the eye- ball, the margin of the upper lid lies midway between the limbus and the pupillary margin of the iris, while the margin of the lower lid is at the limbus. When the eyes are opened normally, the lids are separated from each other by an elliptical space, the palpebral From the Department of Ophthalmology, New York University Post Graduate Medical School, and the University and Lenox Hill Hospitals, New York City. -

Physical Assessment of the Newborn: Part 3

Physical Assessment of the Newborn: Part 3 ® Evaluate facial symmetry and features Glabella Nasal bridge Inner canthus Outer canthus Nasal alae (or Nare) Columella Philtrum Vermillion border of lip © K. Karlsen 2013 © K. Karlsen 2013 Forceps Marks Assess for symmetry when crying . Asymmetry cranial nerve injury Extent of injury . Eye involvement ophthalmology evaluation © David A. ClarkMD © David A. ClarkMD © K. Karlsen 2013 © K. Karlsen 2013 The S.T.A.B.L.E® Program © 2013. Handout may be reproduced for educational purposes. 1 Physical Assessment of the Newborn: Part 3 Bruising Moebius Syndrome Congenital facial paralysis 7th cranial nerve (facial) commonly Face presentation involved delivery . Affects facial expression, sense of taste, salivary and lacrimal gland innervation Other cranial nerves may also be © David A. ClarkMD involved © David A. ClarkMD . 5th (trigeminal – muscles of mastication) . 6th (eye movement) . 8th (balance, movement, hearing) © K. Karlsen 2013 © K. Karlsen 2013 Position, Size, Distance Outer canthal distance Position, Size, Distance Outer canthal distance Normal eye spacing Normal eye spacing inner canthal distance = inner canthal distance = palpebral fissure length Inner canthal distance palpebral fissure length Inner canthal distance Interpupillary distance (midpoints of pupils) distance of eyes from each other Interpupillary distance Palpebral fissure length (size of eye) Palpebral fissure length (size of eye) © K. Karlsen 2013 © K. Karlsen 2013 Position, Size, Distance Outer canthal distance -

The Relationship Between Eyebrow Elevation and Height of The

ORIGINAL http://dx.doi.org/10.14730/aaps.2014.20.1.20 aaps Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg 2014;20(1):20-25 Archives of ARTICLE pISSN: 2234-0831 Aesthetic Plastic Surgery The Relationship Between Eyebrow Elevation and Height of the Palpebral Fissure: Should Postoperative Brow Descent be Taken into Consideration When Determining the Amount of Blepharoptosis Correction? Edward Ilho Lee1, Nam Ho Kim2, Background Combining blepharoptosis correction with double eyelid blepharoplasty Ro Hyuk Park2, Jong Beum Park2, is common in East Asian countries where larger eyes are viewed as attractive. This Tae Joo Ahn2 trend has made understanding the relationship between brow position and height of the palpebral fissure all the more important in understanding post-operative re- 1 Division of Plastic Surgery, Baylor sults. In this study, authors attempt to quantify this relationship in order to assess College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA; whether the expected postoperative brow descent should be taken into consider- 2Gyalumhan Plastic Surgery, Seoul, Korea ation when determining the amount of ptosis to correct. Methods Photographs of ten healthy female study participants were taken with brow at rest, with light elevation and with forceful elevation. These photographs were then viewed at 2×magnification on a computer monitor and caliper was used to measure the amount of pull on the eyebrow in relation to the actual increase in vertical fissure of the eye. Results There was a positive, linear correlation between amount of eyebrow eleva- tion and height of the palpebral fissure, which was statistically significant. Brow ele- vation increased vertical fissure, and thereby aperture of the eye, by 18%. -

A Pictorial Anatomy of the Human Eye/Anophthalmic Socket: a Review for Ocularists

A Pictorial Anatomy of the Human Eye/Anophthalmic Socket: A Review for Ocularists ABSTRACT: Knowledge of human eye anatomy is obviously impor- tant to ocularists. This paper describes, with pictorial emphasis, the anatomy of the eye that ocularists generally encounter: the anophthalmic eye/socket. The author continues the discussion from a previous article: Anatomy of the Anterior Eye for Ocularists, published in 2004 in the Journal of Ophthalmic Prosthetics.1 Michael O. Hughes INTRODUCTION AND RATIONALE B.C.O. Artificial Eye Clinic of Washington, D.C. Understanding the basic anatomy of the human eye is a requirement for all Vienna, Virginia health care providers, but it is even more significant to eye care practition- ers, including ocularists. The type of eye anatomy that ocularists know, how- ever, is more abstract, as the anatomy has been altered from its natural form. Although the companion eye in monocular patients is usually within the normal range of aesthetics and function, the affected side may be distorted. While ocularists rarely work on actual eyeballs (except to cover microph- thalmic and blind, phthisical eyes using scleral cover shells), this knowledge can assist the ocularist in obtaining a naturally appearing prosthesis, and it will be of greater benefit to the patient. An easier exchange among ocularists, surgeons, and patients will result from this knowledge.1, 2, 3 RELATIONSHIPS IN THE NORMAL EYE AND ORBIT The opening between the eyelids is called the palpebral fissure. In the nor- mal eye, characteristic relationships should be recognized by the ocularist to understand the elements to be evaluated in the fellow eye. -

Anatomy of the Periorbital Region Review Article Anatomia Da Região Periorbital

RevSurgicalV5N3Inglês_RevistaSurgical&CosmeticDermatol 21/01/14 17:54 Página 245 245 Anatomy of the periorbital region Review article Anatomia da região periorbital Authors: Eliandre Costa Palermo1 ABSTRACT A careful study of the anatomy of the orbit is very important for dermatologists, even for those who do not perform major surgical procedures. This is due to the high complexity of the structures involved in the dermatological procedures performed in this region. A 1 Dermatologist Physician, Lato sensu post- detailed knowledge of facial anatomy is what differentiates a qualified professional— graduate diploma in Dermatologic Surgery from the Faculdade de Medician whether in performing minimally invasive procedures (such as botulinum toxin and der- do ABC - Santo André (SP), Brazil mal fillings) or in conducting excisions of skin lesions—thereby avoiding complications and ensuring the best results, both aesthetically and correctively. The present review article focuses on the anatomy of the orbit and palpebral region and on the important structures related to the execution of dermatological procedures. Keywords: eyelids; anatomy; skin. RESU MO Um estudo cuidadoso da anatomia da órbita é muito importante para os dermatologistas, mesmo para os que não realizam grandes procedimentos cirúrgicos, devido à elevada complexidade de estruturas envolvidas nos procedimentos dermatológicos realizados nesta região. O conhecimento detalhado da anatomia facial é o que diferencia o profissional qualificado, seja na realização de procedimentos mini- mamente invasivos, como toxina botulínica e preenchimentos, seja nas exéreses de lesões dermatoló- Correspondence: Dr. Eliandre Costa Palermo gicas, evitando complicações e assegurando os melhores resultados, tanto estéticos quanto corretivos. Av. São Gualter, 615 Trataremos neste artigo da revisão da anatomia da região órbito-palpebral e das estruturas importan- Cep: 05455 000 Alto de Pinheiros—São tes correlacionadas à realização dos procedimentos dermatológicos. -

MR and CT Imaging of the Normal Eyelid and Its Application in Eyelid Tumors

cancers Article MR and CT Imaging of the Normal Eyelid and its Application in Eyelid Tumors 1, , 2, 3 1,4 Teresa A. Ferreira * y, Carolina F. Pinheiro y , Paulo Saraiva , Myriam G. Jaarsma-Coes , Sjoerd G. Van Duinen 5, Stijn W. Genders 4, Marina Marinkovic 4 and Jan-Willem M. Beenakker 1,4 1 Department of Radiology, Leiden University Medical Centre, Albinusdreef 2, 2333 ZA Leiden, The Netherlands; [email protected] (M.G.J.-C.); [email protected] (J.-W.M.B.) 2 Department of Neuroradiology, Centro Hospitalar e Universitario de Lisboa Central, Rua Jose Antonio Serrano, 1150-199 Lisboa, Portugal; [email protected] 3 Department of Radiology, Hospital da Luz, Estrada Nacional 10, km 37, 2900-722 Setubal, Portugal; [email protected] 4 Department of Ophthalmology, Leiden University Medical Centre, Albinusdreef 2, 2333 ZA Leiden, The Netherlands; [email protected] (S.W.G.); [email protected] (M.M.) 5 Department of Pathology, Leiden University Medical Centre, Albinusdreef 2, 2333 ZA Leiden, The Netherlands; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Co-first author. y Received: 17 January 2020; Accepted: 24 February 2020; Published: 12 March 2020 Abstract: T-staging of most eyelid malignancies includes the assessment of the integrity of the tarsal plate and orbital septum, which are not clinically accessible. Given the contribution of MRI in the characterization of orbital tumors and establishing their relations to nearby structures, we assessed its value in identifying different eyelid structures in 38 normal eyelids and evaluating tumor extension in three cases of eyelid tumors. -

10||Page SCR JM

JMSCR Vol||3||Issue||10||Page 7712-7718||October 5102 www.jmscr.igmpublication.org Impact Factor 3.79 ISSN (e)-2347-176x DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18535/jmscr/v3i10.02 Oral and Dental Malformations Associated with Treacher Collins Syndrome Ibrahim Gataa School of Dentistry/ University of Sulaimani, Sulaimanya, 053 Iraq Email: [email protected] Mobile Number: 009647701467775 Abstract Treacher Collins syndrome (TCS) is a congenital craniofacial anomaly inherited as an autosomal dominant condition affects both sexes equally with wide variable deformities.The purpose of this study was to highlight the dental and oral malformations associated with this syndrome.A total of eight cases diagnosed to have the syndrome according to minimal obligatory criteria which are malar hypoplasia and downward slanting palpebral fissures were included in the study. Patients’ data were recorded in special formula in addition to oral and dentaldeformities.Seven patients were males one female their age ranged from 10 to 23 years with normal mental status. All patients showed downward slating palpebral fissures, malar hypoplasia .Four patients showed lower eyelid coloboma while six patients (75%) have partial absence of the eyelashes. Oral findings were high arched palate in all cases, malocclusion in 6 cases (75%) and macrostomisa in 4 cases (50%) while multiple impactions of the teeth were detected in four patients. Cleft palate was detected in one case. Dental and oral anomalies associated with this syndrome should be considered in the treatment plan as soon as possible this will improve the quality of the life of the patients and decrease syndrome complications. Keywords: Treacher Collins Syndrome; Mandibulofacial Dysostosis; Craniofacial Anomalies ; Coloboma, Introduction Treacher Collins syndrome (TCS)or Mandibulofacial dysostosis (MFD) is a congenital craniofacial anomaly inherited as an autosomal dominant condition affects both sexes equally. -

The Eye Examination 1

The Eye Examination 1 Objectives Anatomy Eyelids The outer structures that protect the eyeball and lubricate the ocular In order to evaluate the visual system you should be able surface. Within each lid is a tarsal plate containing meibomian glands. to recognize the significant external and internal ocular The lids come together at the medial and lateral canthi. The space between the two open lids is called the palpebral structures of the normal eye and to perform a basic eye fissure. examination. Sclera The thick outer coat of the eye, normally white and opaque. Limbus The junction between the cornea and the sclera. To achieve these objectives, you should learn Iris The colored part of the eye that screens out light, primarily via the pigment epithelium, which lines its posterior surface. Pupil The circular opening in the center of the iris that adjusts the amount of • The essentials of ocular anatomy light entering the eye. Its size is determined by the parasympathetic and • To measure and record visual acuity sympathetic innervation of the iris. Conjunctiva The thin, vascular tissue covering the inner aspect of the • To assess pupillary reflexes eyelids (palpebral conjunctiva) and sclera (bulbar conjunctiva). • To evaluate ocular motility Cornea The transparent front "window" of the eye that serves as the major refractive surface. • To use the direct ophthalmoscope for a systematic Extraocular muscles The six muscles that move the globe medially fundus examination and assessment of the red reflex (medial rectus), laterally (lateral rectus), upward (superior rectus and • To dilate the pupils as an adjunct to ophthalmoscopy inferior oblique), downward (inferior rectus and superior oblique), and torsionally (superior and inferior obliques). -

Eyelid Neurology

Eyelid and Nictitans Movement Michael Davidson Professor, Ophthalmology Diplomate, American College of Veterinary Ophthalmologists Department of Clinical Sciences College of Veterinary Medicine North Carolina State University Raleigh, North Carolina, USA Eyelid Innervation: Efferent Motor Dorsal ramus of CNIII: – Levator palpebral superioris (opening) Palpebral and dorsal buccal branches of CNVII: – obicularis oculi (closure) – levator anguli oculi medialis, frontalis, retractor anguli (opening) – malaris mm. (lower eyelid depressor) Eyelid Muscles Opening: – levator palpebrae superioris m. – frontalis m. – retractor anguli m. – malaris m. – Muller’s m. Closure: – obicularis oculi m. Eyelid Innervation: Sensory Afferent maxillary branch Ophthalmic and ophthalmic branch Maxillary Divisions of CNV mandibular branch trigeminal ganglion trigeminal n. Eyelid Innervation: Sensory Afferent Ophthalmic division CNV: – Frontal n. = upper eyelid, forehead, frontal sinus Frontal n. – Lacrimal n. = lateral orbit, Infratrochlear n. lacrimal gland, upper eyelid, Short Ciliary n. lateral canthus – Nasociliary n.: • Long ciliary nerve = cornea, Long Ciliary n. iris, ciliary body, sclera, sympathetics to eye; Nasociliary n. branches of short ciliary Lacrimal n. nerves (parasympathetics to Ophthalmic branch eye) join long ciliary nerve Zygomatic branch and enter eye Maxillary branch • Infratrochlear nerve = medial canthal skin, medial Trigeminal ganglion conjunctiva, sympathetics to Trigeminal n. upper Muller’s mm. Eyelid Innervation: Sensory Afferent Frontal n. Maxillary division of CNV: Infratrochlear n. – Zygomatic n. to: Short Ciliary n. Zygomaticotemporal Zygomaticofacial • zygomaticofacial = upper eyelid and conjunctiva • zygomaticotemporal = Long Ciliary n. lower eyelid and Nasociliary n. conjunctiva, sympathetics to lower Ophthalmic branch Muller’s m. and Zygomatic branch parasympathetics to Maxillary branch lacrimal gland Trigeminal ganglion Trigeminal n. Eyelid Innervation: Sympathetic Efferent Through terminal Frontal n. branches of trigeminal Infratrochlear n. -

Corneal Topography and the Morphology of the Palpebral Fissure

Corneal topography and the morphology of the palpebral fissure. Scott A. Read B.App.Sc(Optom) Hons Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation School of Optometry Queensland University of Technology Brisbane Australia Submitted as part of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Keywords Keywords Cornea Astigmatism Aberrations Eyelids Corneal topography Videokeratoscopy Digital imaging Eyelid morphology II Abstract Abstract The notion that forces from the eyelids can alter the shape of the cornea has been proposed for many years. In recent times, there has been a marked improvement in our ability to measure and define the corneal shape, allowing subtle changes in the cornea to be measured. These improvements have led to the findings that pressure from the eyelids can cause alterations in corneal shape following everyday visual tasks such as reading. There are also theories to suggest that pressure from the eyelids may be involved in the aetiology of corneal astigmatism. In this program of research, a series of experiments were undertaken to investigate the influence of the eyelids on the shape of the cornea. In the first experiment, an investigation into the diurnal variation of corneal shape was carried out by measuring corneal topography at three different times (approximately 9 am, 1 pm and 5 pm) during the day over three days of the week (Monday, Tuesday and Friday). Highly significant diurnal changes were found to occur in the corneal topography of 15 of the 17 subjects. This change typically consisted of horizontal bands of distortion in the superior, and to a lesser extent, inferior cornea, increasing throughout the day (and returning to baseline the next morning).