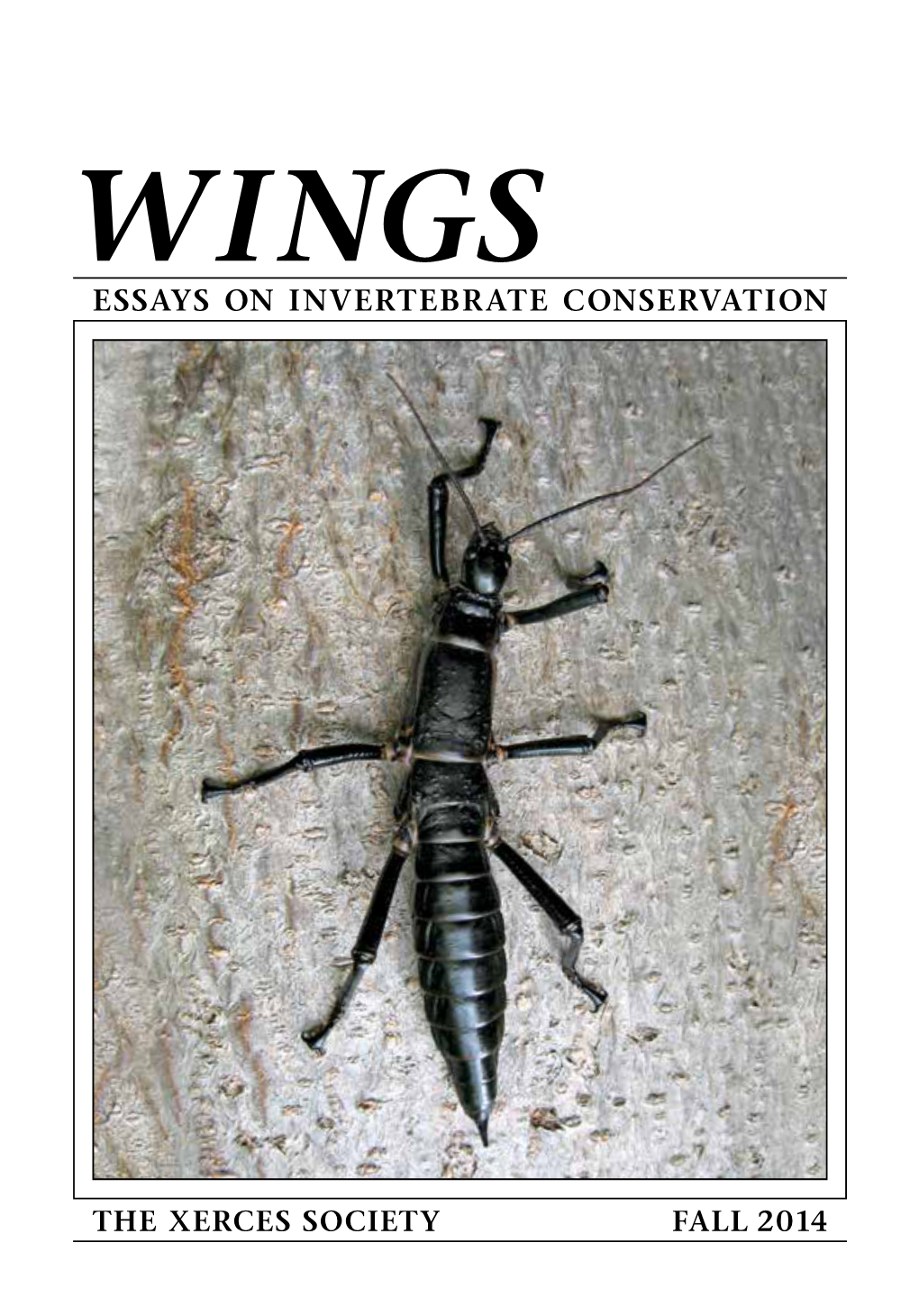

Essays on Invertebrate Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monitoring Dragonfly Migration in North America Protocols for Citizen Scientists

Monitoring Dragonfly Migration in North America Protocols for Citizen Scientists Migratory Dragonfly Partnership Blank on purpose Monitoring Dragonfly Migration in North America Protocols for Citizen Scientists Migratory Dragonfly Partnership Canada • United States • Mexico www.migratorydragonflypartnership.org © 2014 by The Migratory Dragonfly Partnership The Migratory Dragonfly Partnership uses research, citizen science, education, and outreach to under- stand North American dragonfly migration and promote conservation. MDP steering committee members represent a range of organizations, including: Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources; Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum; Pronatura Veracruz; Rutgers University; Slater Museum of Natural History, University of Puget Sound; Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute; St. Edward's University; U. S. Forest Service International Programs; U. S. Geological Survey; Vermont Center for Ecostudies; and the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. Migratory Dragonfly Partnership Project Coordinator, Celeste Mazzacano [email protected] 628 NE Broadway, Suite 200, Portland, OR 97232 Tel (855) 232-6639 Fax (503) 233-6794 www.migratorydragonflypartnership.org Acknowledgements Funding for the Migratory Dragonfly Partnership's work is provided by the U.S. Forest Service Inter- national Programs. We thank the photographers who generously allowed use of their images. Copyright of all photographs remains with the photographers. Front and Back Cover Photographs Common Green Darner (Anax junius) male. Photograph © John C. Abbott/Abbott Nature Photography. CONTENTS Summary Page 1 1. Introduction Page 3 1.1 Objectives and Goals Page 3 Box 1: Citizen Science Projects, page 4. 2. Citizen Science Projects Page 5 2.1 Migration Monitoring Page 5 2.1.1 Fall Migration Observations Page 5 - Objectives, page 5. Box 2: MDP Monitoring Projects, page 6. -

Leopard Frog Predation on Emerging Adults of Colonizing Variegated Meadowhawk Dragonflies David J

LEOPARD FROG PREDATION ON EMERGING ADULTS OF COLONIZING VARIEGATED MEADOWHAWK DRAGONFLIES David J. Larson Box 56 Maple Creek, SK S0N 1N0 [email protected] The early spring of 2016 was very dry in southwestern Saskatchewan. The soil was dry the previous fall and very little snow fell over the winter. Spring melt occurred with no runoff so vernal ponds were empty and water levels in dugouts and dams were low. At a period with so much concern about climate change, one could not help but wonder if this drought presaged future dry conditions. At any rate, it is never a bad idea to try to improve water security. The dry soil meant that heavy equipment could operate without doing too much damage. We hired a track-hoe to come in late April to FIGURE 1. Cactus Flats Dam with water level near capacity. Dragonfly and frog observations were made along dig a dugout and make two dams. the shorelines where the grass was flooded. Photo credit: D. Larson These observations relate to the larger of the dams, which we called and prairie muhly on sandy-clay soil. I took great pleasure in visiting the Cactus Flats Dam in recognition of The term potentially is used because dam each day to watch the water the habitat that was destroyed in our feeling was that it would take level rise. Immediately on holding its construction. It is located on the several years of accumulated runoff water, new life appeared. On the north slope of the Cypress Hills (SW to reach the outflow culvert level, if first night of there being water, an 28 09 26 W3), about 14 km S of ever. -

Redalyc.Papilionidae and Pieridae Butterflies (Lepidoptera

Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie) ISSN: 0065-1737 [email protected] Instituto de Ecología, A.C. México Kir¿ Yanov, Alexander V.; Balcázar Lara, Manuel A. Papilionidae and Pieridae Butterflies (Lepidoptera, Papilionoidea) of the state of Guanajuato, Mexico Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie), vol. 23, núm. 2, 2007, pp. 1-9 Instituto de Ecología, A.C. Xalapa, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=57523201 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Acta ZoológicaActa Mexicana Zool. Mex. (n.s.) (n.s.) 23(2): 23(2) 1-9 (2007) PAPILIONIDAE AND PIERIDAE BUTTERFLIES (LEPIDOPTERA, PAPILIONOIDEA) OF THE STATE OF GUANAJUATO, MEXICO Alexander V. KIR’YANOV* y Manuel A. BALCÁZAR-LARA** *Centro de Investigaciones en Óptica, Loma del Bosque, No. 115, Col. Lomas del Campestre, León 37150, Guanajuato, MÉXICO **Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias, Universidad de Colima, Km 40 Autopista Colima-Manzanillo, Tecomán 28100, Colima, MÉXICO [email protected] [email protected] RESUMEN Presentamos, por primera vez, una lista anotada de las familias Papilionidae y Pieridae (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) para el estado de Guanajuato. Esta lista es el resultado de muestreos sistemáticos de estos taxones en un conjunto de localidades del estado (principalmente en las cercanías de León y la Ciudad de Guanajuato) durante 1998-2004, así como de especímenes depositados en la Colección Nacional de Insectos. Se registran 12 de Papilionidae y 27 especies de Pieridae, de las cuales 4 y 15 respectivamente son nuevos registros para el estado. -

BUTTERFLIES in Thewest Indies of the Caribbean

PO Box 9021, Wilmington, DE 19809, USA E-mail: [email protected]@focusonnature.com Phone: Toll-free in USA 1-888-721-3555 oror 302/529-1876302/529-1876 BUTTERFLIES and MOTHS in the West Indies of the Caribbean in Antigua and Barbuda the Bahamas Barbados the Cayman Islands Cuba Dominica the Dominican Republic Guadeloupe Jamaica Montserrat Puerto Rico Saint Lucia Saint Vincent the Virgin Islands and the ABC islands of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curacao Butterflies in the Caribbean exclusively in Trinidad & Tobago are not in this list. Focus On Nature Tours in the Caribbean have been in: January, February, March, April, May, July, and December. Upper right photo: a HISPANIOLAN KING, Anetia jaegeri, photographed during the FONT tour in the Dominican Republic in February 2012. The genus is nearly entirely in West Indian islands, the species is nearly restricted to Hispaniola. This list of Butterflies of the West Indies compiled by Armas Hill Among the butterfly groupings in this list, links to: Swallowtails: family PAPILIONIDAE with the genera: Battus, Papilio, Parides Whites, Yellows, Sulphurs: family PIERIDAE Mimic-whites: subfamily DISMORPHIINAE with the genus: Dismorphia Subfamily PIERINAE withwith thethe genera:genera: Ascia,Ascia, Ganyra,Ganyra, Glutophrissa,Glutophrissa, MeleteMelete Subfamily COLIADINAE with the genera: Abaeis, Anteos, Aphrissa, Eurema, Kricogonia, Nathalis, Phoebis, Pyrisitia, Zerene Gossamer Wings: family LYCAENIDAE Hairstreaks: subfamily THECLINAE with the genera: Allosmaitia, Calycopis, Chlorostrymon, Cyanophrys, -

Summer 2012 Bulletin of the Oregon Entomological Society

Summer 2012 Bulletin of the Oregon Entomological Society Dragonfly Pond Watch—coming to a wetland near you! Celeste Mazzacano1 Dragonfly Migration Although dragonfly migration has been documented for over 100 years, there is still much to be learned, as we lack defini- Dragonfly migration is one of the most fascinating events in the tive answers to questions surrounding the environmental cues insect world, but also one of the least-known. This is even more that trigger migration, the adaptive advantages gained by the surprising when you consider that dragonfly migration occurs on subset of odonate species that migrate, reproductive activity of every continent except Antarctica. When people think of insect migration, the Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) is a familiar figure, but the Wandering Glider (Pantala flavescens), a widely distributed species also known as a regular mi- grant in North America, can travel 11,000 miles (17,700 km) across the Indian Ocean from Africa to India and back—more than twice the distance of the Monarch’s well-known annual journey. Only about 16 of our 326 dragonfly species in North America are regular migrants, with some making annual seasonal flights while others are more sporadic. The major migratory species in North America are Common Green Darner (Anax junius), Wandering Glider (Pantala flave- scens), Spot-winged Glider (P. hymenaea), Black Saddlebags (Tramea lacerata), and Variegated Meadowhawk (Sympetrum corruptum). Different species tend to dominate migration flights in different parts of the continent. Anax junius is our best-known migrant, moving in Common Green Darner (Anax junius) at North Bend, Coos County, Oregon. -

Butterflies and Moths of Dominican Republic

Heliothis ononis Flax Bollworm Moth Coptotriche aenea Blackberry Leafminer Argyresthia canadensis Apyrrothrix araxes Dull Firetip Phocides pigmalion Mangrove Skipper Phocides belus Belus Skipper Phocides palemon Guava Skipper Phocides urania Urania skipper Proteides mercurius Mercurial Skipper Epargyreus zestos Zestos Skipper Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus spanna Hispaniolan Silverdrop Epargyreus exadeus Broken Silverdrop Polygonus leo Hammock Skipper Polygonus savigny Manuel's Skipper Chioides albofasciatus White-striped Longtail Chioides zilpa Zilpa Longtail Chioides ixion Hispaniolan Longtail Aguna asander Gold-spotted Aguna Aguna claxon Emerald Aguna Aguna metophis Tailed Aguna Typhedanus undulatus Mottled Longtail Typhedanus ampyx Gold-tufted Skipper Polythrix octomaculata Eight-spotted Longtail Polythrix mexicanus Mexican Longtail Polythrix asine Asine Longtail Polythrix caunus (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) Zestusa dorus Short-tailed Skipper Codatractus carlos Carlos' Mottled-Skipper Codatractus alcaeus White-crescent Longtail Codatractus yucatanus Yucatan Mottled-Skipper Codatractus arizonensis Arizona Skipper Codatractus valeriana Valeriana Skipper Urbanus proteus Long-tailed Skipper Urbanus viterboana Bluish Longtail Urbanus belli Double-striped Longtail Urbanus pronus Pronus Longtail Urbanus esmeraldus Esmeralda Longtail Urbanus evona Turquoise Longtail Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail Urbanus teleus Teleus Longtail Urbanus tanna Tanna Longtail Urbanus simplicius Plain Longtail Urbanus procne Brown Longtail -

Microsoft Outlook

Joey Steil From: Leslie Jordan <[email protected]> Sent: Tuesday, September 25, 2018 1:13 PM To: Angela Ruberto Subject: Potential Environmental Beneficial Users of Surface Water in Your GSA Attachments: Paso Basin - County of San Luis Obispo Groundwater Sustainabilit_detail.xls; Field_Descriptions.xlsx; Freshwater_Species_Data_Sources.xls; FW_Paper_PLOSONE.pdf; FW_Paper_PLOSONE_S1.pdf; FW_Paper_PLOSONE_S2.pdf; FW_Paper_PLOSONE_S3.pdf; FW_Paper_PLOSONE_S4.pdf CALIFORNIA WATER | GROUNDWATER To: GSAs We write to provide a starting point for addressing environmental beneficial users of surface water, as required under the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA). SGMA seeks to achieve sustainability, which is defined as the absence of several undesirable results, including “depletions of interconnected surface water that have significant and unreasonable adverse impacts on beneficial users of surface water” (Water Code §10721). The Nature Conservancy (TNC) is a science-based, nonprofit organization with a mission to conserve the lands and waters on which all life depends. Like humans, plants and animals often rely on groundwater for survival, which is why TNC helped develop, and is now helping to implement, SGMA. Earlier this year, we launched the Groundwater Resource Hub, which is an online resource intended to help make it easier and cheaper to address environmental requirements under SGMA. As a first step in addressing when depletions might have an adverse impact, The Nature Conservancy recommends identifying the beneficial users of surface water, which include environmental users. This is a critical step, as it is impossible to define “significant and unreasonable adverse impacts” without knowing what is being impacted. To make this easy, we are providing this letter and the accompanying documents as the best available science on the freshwater species within the boundary of your groundwater sustainability agency (GSA). -

Thanked for the Line Drawing. Brunsvigia Heist., a Genus of About

34 Bothalia 31,1 (20()1) WESTERN CAPE.—3321 (Ladismith): Attakwas- REFERENCES kloof, near summit of old Voortrekker Pass, (-DD), DYER. R.A. 1977. Cyrtanthus montanus. The Flowering Plants of Oliver 4134 (NBG, PRE). 3322 (Oudtshoom): northern Africa 44: t. 1756. slopes of Outeniqua Mountains, along Groot Doomrivier, DYER. R.A. 1980. A new species of Cyrtanthus from the Baviaans (-CC), Viviers & Vlok 370 (NBG); Outeniqua Mountains, kloof, southeastern Cape. Bothalia 13: 135. near summit of Robinson Pass, Snijman & Vlok 1717 (K, NORDAL. I. 1979. Revision of the genus Cyrtanthus (Amaryllidaceae) in East Africa. Norwegian Journal of Botany 26: 183-192. NBG, PRE); Ruytersbosch, Gemmell sub BLFU5032 REID. C. & DYER. R.A. 1984. A review o f the southern African species (BLFU, PRE); Jonkersberg on south-facing slopes of o/Cyrtanthus. American Plant Life Society, La Jolla. Bolleberg, Vlok 814 (PRE). SAUNDERS. R. & SAUNDERS. R. 2000. Does fynbos need to bum? Veld & Flora 86: 76-78. SNIJMAN. D.A. 1999. New species and notes on Cyrtanthus in the ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS southern Cape, South Africa. Bothalia 29: 258-263. SNIJMAN. D.A. & VAN JAARSVELD. E.J. 1995. Cyrtanthus flam- I am grateful to the Western Cape Nature Conservation mosus. Flowering Plants of Africa 54: 100-103. Board for granting me permission to collect plants in the wild; Jan and Anne Lise Vlok for their generous help and D.A. SNIJMAN* hospitality; and Colin Paterson-Jones for invaluable * Compton Herbarium, National Botanical Institute, Private Bag X7, assistance in the field. Claire Linder Smith is sincerely 7735 Claremont, Cape Town. thanked for the line drawing. -

Backyard Butterflies, Lepidopterology Study & ID Guide

Lepidopterology is the study of butterflies and moths. See how many of these common central Florida butterflies you can find and identify. Record your observations in the boxes next to each species. Butterflies with Orange Coloration - From the largest (monarch) to smallest (phaon crescent and little metalmark), look for these species in parks and gardens, fields, forest edges, on roadsides, streambanks, and shorelines. Monarch Viceroy Queen (Danaus plexippus) (Limenitis archippus) (Danaus gilippus) Red Admiral Gulf Fritillary Variegated American (Vanessa atalanta) (Agraulis vanillae) Fritillary (Painted) Lady (Euptoieta claudia) (Vanessa virginiensis) Question Mark Hackberry White Common (Polygonia Emperor Peacock Buckeye interrogationis) (Asterocampa celtis) (Anartia jatrophae) (Junonia coenia) American Snout Fiery Skipper Pearl Crescent Little (Libytheana (Hylephila phyleus) (Phyciodes tharos) Metalmark carinenta) (Calephelis virginiensis) Whites and Sulphurs - Most species of family Pieridae are white, yellow, or orange; some with black markings. Great Southern Cloudless Orange-barred Southern White Sulphur Sulphur Dogface (Ascia monuste) (Phoebis sennae) (Phoebis philea) (Zerene cesonia) “Exceptional”s - Look for zebra heliconian, Florida’s state butterfly, in shaded woodland edges. The giant luna isn’t a butterfly, but with luck you may spy this moth by day. Red-spotted purples mimic the distasteful pipevine swallowtails. Zebra Longwing Luna Moth Red-spotted Purple (Heliconius charithonia) (Actias luna) (Limenitis arthemis astyanax) -

Dragonflies and Damselflies Havasu National Wildlife Refuge

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Dragonflies and Damselflies Havasu National Wildlife Refuge Dragonfly and damselfly at Havasu National Wildlife Refuge There are twenty-five dragonfly and damselfly species listed at the 37,515 acre Havasu National Wildlife Refuge, one of more than 540 refuges throughout the United States. These National Wildlife Refuges are administered by the Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. The Fish and Wildlife Service mission is to work with others “to conserve fish and wildlife and their habitat.” General Information Havasu National Wildlife Refuge encompasses 37,515 acres adjacent to the Colorado River. Topock Marsh, Topock Gorge, and the Havasu Wilderness constitute the three major portions of the refuge. Dragonflies, an important Male blue-ringed dancer sedula indicator of water quality, can be found © Dave Welling Photography on the refuge, primarily in Topock Marsh Libellula luctuosa Tramea onusta and Topock Gorge. Dragonflies can be Widow Skimmer Red Saddlebags viewed on the refuge year-round, with hot, sunny days providing some of the L. pulchella Pond Damsels–Dancers (Coenagrionidae) best viewing. Sixty-three dragonfly and Twelve-spotted Skimmer Argia moesta damsel species have been identified in Powdered Dancer Mohave County, Arizona. Visitors are L. saturate encouraged to contact refuge staff with a Flame Skimmer Argia sedula description or photograph, if an unlisted Blue-ringed Dancer species is observed. Pachydiplax longipennis Blue Dasher Enallagma civile Family Familiar Bluet Scientific -

The Influence of Host Plant Extrafloral Nectaries on Multitrophic Interactions: an Experimental Investigation

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons Department of Biological Sciences College of Arts, Sciences & Education 9-22-2015 The nflueI nce of Host Plant Extrafloral Nectaries on Multitrophic Interactions: An Experimental Investigation Suzanne Koptur Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, [email protected] Ian M. Jones Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, [email protected] Jorge E. Pena University of Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/cas_bio Recommended Citation Koptur S, Jones IM, Peña JE (2015) The nflueI nce of Host Plant Extrafloral Nectaries on Multitrophic Interactions: An Experimental Investigation. PLoS ONE 10(9): e0138157. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138157 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Biological Sciences by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESEARCH ARTICLE The Influence of Host Plant Extrafloral Nectaries on Multitrophic Interactions: An Experimental Investigation Suzanne Koptur1*, Ian M. Jones1, Jorge E. Peña2 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, Miami, Florida, United States of America, 2 Tropical Research and Education Center, University of Florida, Homestead, Florida, United States of America * [email protected] a11111 Abstract A field experiment was conducted with outplantings of the native perennial shrub Senna mexicana var. chapmanii in a semi-natural area adjacent to native pine rockland habitat in southern Florida. The presence of ants and the availability of extrafloral nectar were manip- ulated in a stratified random design. -

Pieridae of Arkansas E

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 23 Article 17 1969 Pieridae of Arkansas E. Phil Rouse University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Rouse, E. Phil (1969) "Pieridae of Arkansas," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 23 , Article 17. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol23/iss1/17 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 23 [1969], Art. 17 94 Arkansas Academy of Science Proceedings, Vol. 23, 1969 THE PIERIDAE OF ARKANSAS E. Phil Rouse Entomology Department, University of Arkansas The members of the family Pieridae are medium to small sized butterflies usually having white, yellow, or orange background color, with dark gray or black marginal wing markings. The radius may be three or four branches, rarely five, and some branches are always stalked in the front wing. The cubitus appears three branched (Fig.. 1). There are always two anal veins present in the hind wing.