Review of Pollinators and Pollination Relevant to the Conservation And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Following the Cold

Systematic Entomology (2018), 43, 200–217 DOI: 10.1111/syen.12268 Following the cold: geographical differentiation between interglacial refugia and speciation in the arcto-alpine species complex Bombus monticola (Hymenoptera: Apidae) BAPTISTE MARTINET1 , THOMAS LECOCQ1,2, NICOLAS BRASERO1, PAOLO BIELLA3,4, KLÁRA URBANOVÁ5,6, IRENA VALTEROVÁ5, MAURIZIO CORNALBA7,JANOVE GJERSHAUG8, DENIS MICHEZ1 andPIERRE RASMONT1 1Laboratory of Zoology, Research Institute of Biosciences, University of Mons, Mons, Belgium, 2Research Unit Animal and Functionalities of Animal Products (URAFPA), University of Lorraine-INRA, Vandoeuvre-lès-Nancy, France, 3Faculty of Science, Department of Zoology, University of South Bohemia, Ceskéˇ Budejovice,ˇ Czech Republic, 4Biology Centre of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, v.v.i., Institute of Entomology, Ceskéˇ Budejovice,ˇ Czech Republic, 5Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry, Prague, Czech Republic, 6Faculty of Tropical AgriSciences, Department of Sustainable Technologies, Czech University of Life Sciences, Prague, Czech Republic, 7Department of Mathematics, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy and 8Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, Trondheim, Norway Abstract. Cold-adapted species are expected to have reached their largest distribution range during a part of the Ice Ages whereas postglacial warming has led to their range contracting toward high-latitude and high-altitude areas. This has resulted in an extant allopatric distribution of populations and possibly to trait differentiations (selected or not) or even speciation. Assessing inter-refugium differentiation or speciation remains challenging for such organisms because of sampling difficulties (several allopatric populations) and disagreements on species concept. In the present study, we assessed postglacial inter-refugia differentiation and potential speciation among populations of one of the most common arcto-alpine bumblebee species in European mountains, Bombus monticola Smith, 1849. -

Classification of the Apidae (Hymenoptera)

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Mi Bee Lab 9-21-1990 Classification of the Apidae (Hymenoptera) Charles D. Michener University of Kansas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/bee_lab_mi Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Michener, Charles D., "Classification of the Apidae (Hymenoptera)" (1990). Mi. Paper 153. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/bee_lab_mi/153 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Bee Lab at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 4 WWvyvlrWryrXvW-WvWrW^^ I • • •_ ••^«_«).•>.• •.*.« THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS SCIENC5;^ULLETIN LIBRARY Vol. 54, No. 4, pp. 75-164 Sept. 21,1990 OCT 23 1990 HARVARD Classification of the Apidae^ (Hymenoptera) BY Charles D. Michener'^ Appendix: Trigona genalis Friese, a Hitherto Unplaced New Guinea Species BY Charles D. Michener and Shoichi F. Sakagami'^ CONTENTS Abstract 76 Introduction 76 Terminology and Materials 77 Analysis of Relationships among Apid Subfamilies 79 Key to the Subfamilies of Apidae 84 Subfamily Meliponinae 84 Description, 84; Larva, 85; Nest, 85; Social Behavior, 85; Distribution, 85 Relationships among Meliponine Genera 85 History, 85; Analysis, 86; Biogeography, 96; Behavior, 97; Labial palpi, 99; Wing venation, 99; Male genitalia, 102; Poison glands, 103; Chromosome numbers, 103; Convergence, 104; Classificatory questions, 104 Fossil Meliponinae 105 Meliponorytes, -

Bombus Ruderatus)

SPECIES MANAGEMENT SHEET Large garden bumblebee (Bombus ruderatus) This bumblebee is Britain’s biggest and has a long Distribution map face and tongue, which allow it to feed from long- tubed flowers. These bees are black with two yellow The Large garden bumblebee was bands on top of the body, a single yellow band on the once very common in southern and bottom and a white tail, however there is also a central England but has been lost totally black form. The Large garden bumblebee has from over 80% of its known declined in numbers and due to threats it faces has localities over the last 100 years. In been identified as a Species of Principal Importance. the UK it is now mainly found in the Fens, East Midlands and Life cycle Cambridgeshire. Their annual life cycle sees queens emerge from Large garden bumblebee hibernation from April to June, with workers flying (Post-2000 records - the information used here was sourced through the NBN Gateway. Contains OS data © Crown Copyright 2016) from June to August and males in flight during July and August. New queens hibernate from October ready to Habitat emerge the following spring. The Large garden bumblebee is mostly associated with flower-rich meadows and wetlands. It has survived Reasons for decline successfully in the fens and river valleys of eastern Agricultural intensification as well as forestry and England, however it also uses intensively farmed areas development have all resulted in the loss of large areas with flower-rich ditches, field margins or organic clover of flower-rich grassland, wet grassland and ditches, leys. -

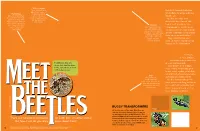

Buggy Transformers

Wing Coverings They’re called elytra It’s liftoff! A scarab beetle (see (EL-ih-truh), and most Flight Wings beetles have them. photo) flaps its wings and rises Also called hind wings, Elytra are hard and into the air. they’re thin and delicate. tough. They protect the Beetles aren’t the best When not being used, delicate flight wings they fold under the elytra. underneath. fliers in the insect world. But But when it’s time to fly, that doesn’t stop them from these wings pop open Antennas and beat up and Most beetles use them being among the world’s great- down rapidly. for smelling. But some est success stories. Out of all the can use them for tasting, feeling, or even swimming species of animals on our planet, or fighting! They can be three out of ten are beetles! shaped like clubs, saw blades, feathers, They crawl, fly, hop, and or strings of beads. swim on every continent except Antarctica. You’ll find them in forests, deserts, prairies, mountain regions, and even Fossils like this one in your own backyard. show that beetles have Some beetles look strange. been around for at least Parts of their bodies may grow 300 million years. horns, crests, spikes, or brushes. Several beetles have long snouts, Legs Like all insects, and many are wildly colorful. beetles have six Beetles do weird things, too. jointed legs. Most beetles have two tiny claws on Some species eat dung, and a few the tip of each leg for even squirt out hot liquids. -

Wildlife Review Cover Image: Hedgehog by Keith Kirk

Dumfries & Galloway Wildlife Review Cover Image: Hedgehog by Keith Kirk. Keith is a former Dumfries & Galloway Council ranger and now helps to run Nocturnal Wildlife Tours based in Castle Douglas. The tours use a specially prepared night tours vehicle, complete with external mounted thermal camera and internal viewing screens. Each participant also has their own state- of-the-art thermal imaging device to use for the duration of the tour. This allows participants to detect animals as small as rabbits at up to 300 metres away or get close enough to see Badgers and Roe Deer going about their nightly routine without them knowing you’re there. For further information visit www.wildlifetours.co.uk email [email protected] or telephone 07483 131791 Contributing photographers p2 Small White butterfly © Ian Findlay, p4 Colvend coast ©Mark Pollitt, p5 Bittersweet © northeastwildlife.co.uk, Wildflower grassland ©Mark Pollitt, p6 Oblong Woodsia planting © National Trust for Scotland, Oblong Woodsia © Chris Miles, p8 Birdwatching © castigatio/Shutterstock, p9 Hedgehog in grass © northeastwildlife.co.uk, Hedgehog in leaves © Mark Bridger/Shutterstock, Hedgehog dropping © northeastwildlife.co.uk, p10 Cetacean watch at Mull of Galloway © DGERC, p11 Common Carder Bee © Bob Fitzsimmons, p12 Black Grouse confrontation © Sergey Uryadnikov/Shutterstock, p13 Black Grouse male ©Sergey Uryadnikov/Shutterstock, Female Black Grouse in flight © northeastwildlife.co.uk, Common Pipistrelle bat © Steven Farhall/ Shutterstock, p14 White Ermine © Mark Pollitt, -

Abou-Shaara, Hossam I Am Assistant Lecturer at Faculty of Agriculture

Abou‐Shaara, Hossam I am assistant lecturer at Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Pest Control and Environmental Protection, Alexandria University,Damanhour Branch, Egypt. The title of my Master’s thesis is “Morphometric, Biological, Behavioral studies on some honey bee races at El‐Behera governorate.” I currently have four papers in preparation for publication and I have patented seven beekeeping inventions. I maintain my own apiary in Damanhour city and I am a member in Beekeeping association Alexandria governorate, Egypt. Dept. of Pest Control & Environmental Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, Damanhour Branch, Alexandria University, El‐Goumhoria St., PO Box 22516, Damanhour, El‐Behra Governorate, EGYPT Phone: 002‐019‐634‐9607, Fax: 002‐045‐331‐6535, Email: [email protected] Adams, Eldridge S. Dept. Ecol. and Evol. Biol., University of Connecticut, 75 N. Eagleville Rd., U‐43, Storrs, CT 06269‐3043, USA Phone: 860‐486‐5894, Fax: 860‐486‐6364, Email: [email protected] Homepage: http://hydrodictyon.eeb.uconn.edu/people/adams/ Adams, Rachelle M.M. My research interests encompass the integration of three fields, chemical ecology, behavioral ecology and evolutionary biology. Using the Megalomyrmex ant genus as a model system, I study the evolution of social parasitic behavior and colony infiltration strategies. Centre for Social Evolution, Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen Universitetsparken 15 DK‐ 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark Smithsonian Institute, PO Box 37012, MRC 188, Washington, DC, 20013‐7012, USA Phone: 202‐633‐1002, Email: [email protected] Homepage: http://www1.bio.ku.dk/english/research/oe/cse/ and http://entomology.si.edu/StaffPages/AdamsRMM.html Al‐Ghamdi, Ahmad Al Khazim Bee Research Unit, Plant Protection Department, Faculty of Science of Food and Agriculture, King Saud University, P.O. -

Recursos Florales Usados Por Dos Especies De Bombus En Un Fragmento De Bosque Subandino (Pamplonita-Colombia)

ARTÍCULO ORIGINAL REVISTA COLOMBIANA DE CIENCIA ANIMAL Rev Colombiana Cienc Anim 2017; 9(1):31-37. Recursos florales usados por dos especies de Bombus en un fragmento de bosque subandino (Pamplonita-Colombia) Floral resources use by two species of Bombus in a subandean forest fragment (Pamplonita-Colombia) 1* 2 3 Mercado-G, Jorge M.Sc, Solano-R, Cristian Biol, Wolfgang R, Hoffmann Biol. 1Universidad de Sucre, Departamento de Biología y Química, Grupo Evolución y Sistemática Tropical. Sincelejo. Colombia. 2IANIGLA, Departamento de Paleontología, CCT CONICET. Mendoza, Argentina. 3Universidad de Pamplona, Facultad de Ciencias Básicas, Grupo de Biocalorimetría. Pamplona, Colombia Keywords: Abstract Pollen; It is present the results of a palynological analysis of two species of the genus palinology; Bombus in vicinity of Pamplonita-Norte of Santander. On feces samples were diet; identified and counted (april and may of 2010) 1585 grains of pollen, within which Norte de Santander; Solanaceae, Asteraceae, Malvaceae and Fabaceae were the more abundat taxa. Hymenoptera, feces. With regard to the diversity, April was the most rich, diverse and dominant month; however in B. pullatus we observed greater wealth and dominance. Finally, it was possible to determine that a large percentage of pollen grains that were identified as Solanaceae correspond to Solanum quitoense. The results of this study make clear the importance of palynology at the time of establishing the diet of these species, in addition to reflect its role of those species as possible provider in ecosistemic services either in wild plant as a crops in Solanaceae case. Palabras Clave: Resumen Polen; Se presentan los resultados de un análisis palinológico en dos especies del palinología; género Bombus en cercanías de Pamplonita (Norte de Santander-Colombia) dieta; durante los meses de abril y mayo de 2010. -

Growing a Wild NYC: a K-5 Urban Pollinator Curriculum Was Made Possible Through the Generous Support of Our Funders

A K-5 URBAN POLLINATOR CURRICULUM Growing a Wild NYC LESSON 1: HABITAT HUNT The National Wildlife Federation Uniting all Americans to ensure wildlife thrive in a rapidly changing world Through educational programs focused on conservation and environmental knowledge, the National Wildlife Federation provides ways to create a lasting base of environmental literacy, stewardship, and problem-solving skills for today’s youth. Growing a Wild NYC: A K-5 Urban Pollinator Curriculum was made possible through the generous support of our funders: The Seth Sprague Educational and Charitable Foundation is a private foundation that supports the arts, housing, basic needs, the environment, and education including professional development and school-day enrichment programs operating in public schools. The Office of the New York State Attorney General and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation through the Greenpoint Community Environmental Fund. Written by Nina Salzman. Edited by Sarah Ward and Emily Fano. Designed by Leslie Kameny, Kameny Design. © 2020 National Wildlife Federation. Permission granted for non-commercial educational uses only. All rights reserved. September - January Lesson 1: Habitat Hunt Page 8 Lesson 2: What is a Pollinator? Page 20 Lesson 3: What is Pollination? Page 30 Lesson 4: Why Pollinators? Page 39 Lesson 5: Bee Survey Page 45 Lesson 6: Monarch Life Cycle Page 55 Lesson 7: Plants for Pollinators Page 67 Lesson 8: Flower to Seed Page 76 Lesson 9: Winter Survival Page 85 Lesson 10: Bee Homes Page 97 February -

Global Trends in Bumble Bee Health

EN65CH11_Cameron ARjats.cls December 18, 2019 20:52 Annual Review of Entomology Global Trends in Bumble Bee Health Sydney A. Cameron1,∗ and Ben M. Sadd2 1Department of Entomology, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA; email: [email protected] 2School of Biological Sciences, Illinois State University, Normal, Illinois 61790, USA; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020. 65:209–32 Keywords First published as a Review in Advance on Bombus, pollinator, status, decline, conservation, neonicotinoids, pathogens October 14, 2019 The Annual Review of Entomology is online at Abstract ento.annualreviews.org Bumble bees (Bombus) are unusually important pollinators, with approx- https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-011118- imately 260 wild species native to all biogeographic regions except sub- 111847 Saharan Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. As they are vitally important in Copyright © 2020 by Annual Reviews. natural ecosystems and to agricultural food production globally, the increase Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020.65:209-232. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org All rights reserved in reports of declining distribution and abundance over the past decade ∗ Corresponding author has led to an explosion of interest in bumble bee population decline. We Access provided by University of Illinois - Urbana Champaign on 02/11/20. For personal use only. summarize data on the threat status of wild bumble bee species across bio- geographic regions, underscoring regions lacking assessment data. Focusing on data-rich studies, we also synthesize recent research on potential causes of population declines. There is evidence that habitat loss, changing climate, pathogen transmission, invasion of nonnative species, and pesticides, oper- ating individually and in combination, negatively impact bumble bee health, and that effects may depend on species and locality. -

List of Insect Species Which May Be Tallgrass Prairie Specialists

Conservation Biology Research Grants Program Division of Ecological Services © Minnesota Department of Natural Resources List of Insect Species which May Be Tallgrass Prairie Specialists Final Report to the USFWS Cooperating Agencies July 1, 1996 Catherine Reed Entomology Department 219 Hodson Hall University of Minnesota St. Paul MN 55108 phone 612-624-3423 e-mail [email protected] This study was funded in part by a grant from the USFWS and Cooperating Agencies. Table of Contents Summary.................................................................................................. 2 Introduction...............................................................................................2 Methods.....................................................................................................3 Results.....................................................................................................4 Discussion and Evaluation................................................................................................26 Recommendations....................................................................................29 References..............................................................................................33 Summary Approximately 728 insect and allied species and subspecies were considered to be possible prairie specialists based on any of the following criteria: defined as prairie specialists by authorities; required prairie plant species or genera as their adult or larval food; were obligate predators, parasites -

Colias Ponteni 47 Years of Investigation, Thought and Speculations Over a Butterfly

Insectifera VOLUME 11 • YEAR 2019 2019 YEAR • SPECIAL ISSUE Colias ponteni 47 years of investigation, thought and speculations over a butterfly INSECTIFERA • YEAR 2019 • VOLUME 11 Insectifera December 2019, Volume 11 Special Issue Editor Pavel Bína & Göran Sjöberg Sjöberg, G. 2019. Colias ponteni Wallengren, 1860. 47 years of investigation, thought and speculations over a butterfly. Insectifera, Vol. 11: 3–100. Contents 4 Summary 4 My own reflections 5 The background to the first Swedish scientific sailing round the world, 1851–1853 16 Extreme sex patches – androconia and antennae 20 Colias ponteni in the collection of BMNH. Where do they come from? Who have collected them and where and when? 22 Two new Colias ponténi and a pupa! 24 Hawaii or Port Famine? Which locality is most likely to be an objective assessment? 25 Colias ponteni - a sensitive "primitive species". Is it extinct? 26 Cause of likely extinction 28 IRMS (Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer) isotope investigations 29 What more can suggest that Samuel Pontén's butterflies really were taken in Hawaii? 30 Can Port Famine or the surrounding areas be the right place for Colias ponteni? 34 Collection on Oahu 37 Is there more that suggests that Samuel Pontén found his Colias butterflies during this excursion on Oahu near Honolulu? 38 The background to my studies 39 Is there something that argues against Port Famine as a collection site for Colias ponteni? 39 Is it likely that the butterflies exist or may have been on Mt Tarn just south of Port Famine on the Strait of Magellan? 41 -

Behavioral Phylogeny of Corbiculate Apidae (Hymenoptera; Apinae), with Special Reference to Social Behavior

Cladistics 18, 137±153 (2002) doi:10.1006/clad.2001.0191, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on Behavioral Phylogeny of Corbiculate Apidae (Hymenoptera; Apinae), with Special Reference to Social Behavior Fernando B. Noll1 Museum of Biological Diversity, Department of Entomology, The Ohio State University, 1315 Kinnear Road, Columbus, Ohio 43212 Accepted September 25, 2000 The phylogenetic relationships among the four tribes of Euglossini (orchid bees, about 175 species), Bombini corbiculate bees (Euglossini, Bombini, Meliponini, and (bumblebees, about 250 species), Meliponini (stingless Apini) are controversial. There is substantial incongru- bees, several hundred species), and Apini (honey bees, ence between morphological and molecular data, and the about 11 species) (Michener, 2000), that belong to the single origin of eusociality is questionable. The use of Apinae, a subfamily of long-tongued bees. They all behavioral characters by previous workers has been possess apical combs (the corbiculae) on the females' restricted to some typological definitions, such as soli- tibiae as well as several other morphological synapo- tary and eusocial. Here, I expand the term ªsocialº to 42 morphies (with the exception of the parasitic forms, characters and present a tree based only on behavioral and the queens of highly eusocial species). In addition, characters. The reconstructed relationships were similar with the exception of the Euglossini and the social to those observed in morphological and ªtotal evidenceº parasite Psithyrus in Bombini, all corbiculate bees are ؉ ؉ ؉ analyses, i.e., Euglossini (Bombini (Meliponini social. Apini)), all of which support a single origin of euso- Despite many studies that have focused on the classi- ciality. ᭧ 2002 The Willi Hennig Society ®cation and phylogeny of bees, many authors do not agree on one classi®cation and one phylogeny.