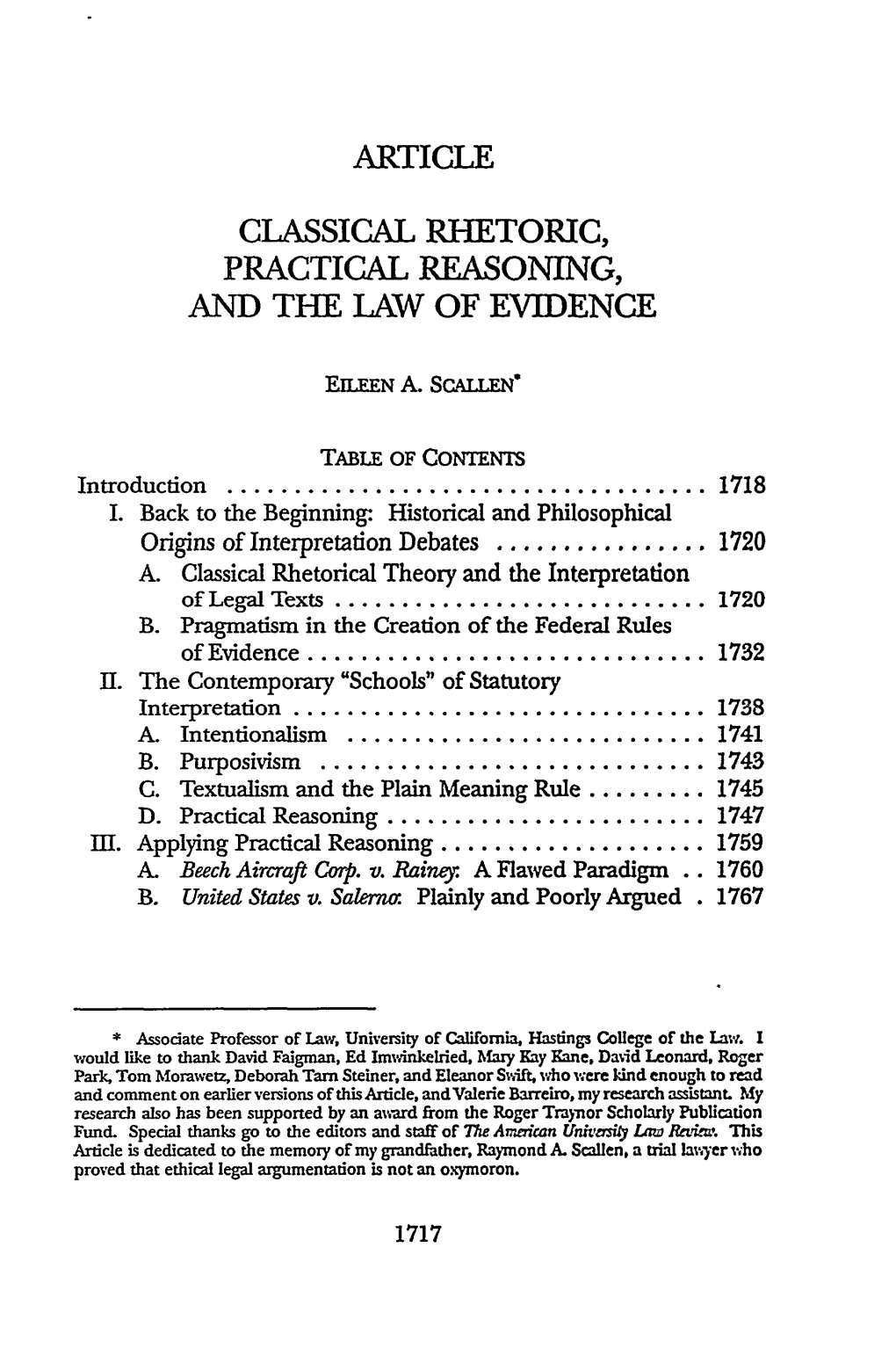

Article Classical Rhetoric, Practical Reasoning, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhetoric and Law: How Do Lawyers Persuade Judges? How Do Lawyers Deal with Bias in Judges and Judging?

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Honors Theses Department of English 5-9-2015 Rhetoric And Law: How Do Lawyers Persuade Judges? How Do Lawyers Deal With Bias In Judges And Judging? Danielle Barnwell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_hontheses Recommended Citation Barnwell, Danielle, "Rhetoric And Law: How Do Lawyers Persuade Judges? How Do Lawyers Deal With Bias In Judges And Judging?." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2015. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_hontheses/10 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RHETORIC AND LAW: HOW DO LAWYERS PERSUADE JUDGES? HOW DO LAWYERS DEAL WITH BIAS IN JUDGES AND JUDGING? By: Danielle Barnwell Under the Direction of Dr. Beth Burmester An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Undergraduate Research Honors in the Department of English Georgia State University 2014 ______________________________________ Honors Thesis Advisor ______________________________________ Honors Program Associate Dean ______________________________________ Date RHETORIC AND LAW: HOW DO LAWYERS PERSUADE JUDGES? HOW DO LAWYERS DEAL WITH BIAS IN JUDGES AND JUDGING? BY: DANIELLE BARNWELL Under the Direction of Dr. Beth Burmester ABSTRACT Judges strive to achieve both balance and fairness in their rulings and courtrooms. When either of these is compromised, or when judicial discretion appears to be handed down or enforced in random or capricious ways, then bias is present. -

Judicial Rhetoric and Radical Politics: Sexuality, Race, and the Fourteenth Amendment

JUDICIAL RHETORIC AND RADICAL POLITICS: SEXUALITY, RACE, AND THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT BY PETER O. CAMPBELL DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Speech Communication with a minor in Gender and Women’s Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Kent A. Ono, Chair Associate Professor Cara A. Finnegan Associate Professor Pat Gill Associate Professor Thomas O’Gorman Associate Professor Siobhan B. Somerville ABSTRACT: “Judicial Rhetoric and Radical Politics: Sexuality, Race, and the Fourteenth Amendment” takes up U.S. judicial opinions as performances of sovereignty over the boundaries of legitimate subjectivity. The argumentative choices jurists make in producing judicial opinion delimit the grounds upon which persons and groups can claim existence as legal subjects in the United States. I combine doctrinal, rhetorical, and queer methods of legal analysis to examine how judicial arguments about due process and equal protection produce different possibilities for the articulation of queer of color identity in, through, and in response to judicial speech. The dissertation includes three case studies of opinions in state, federal and Supreme Court cases (including Lawrence v. Texas, Parents Involved in Community Schools vs. Seattle School District No. 1, & Perry v. Brown) that implicate U.S. Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy’s development and application of a particular form of Fourteenth Amendment rhetoric that I argue has liberatory potential from the perspective of radical (anti-establishmentarian and statist) queer politics. I read this queer potential in Kennedy’s substantive due process and equal protection arguments about gay and lesbian civil rights as a component part of his broader rhetorical constitution of a newly legitimated and politically regressive post-racial queer subject position within the U.S. -

Athenian Homicide Rhetoric in Context

ATHENIAN HOMICIDE RHETORIC IN CONTEXT BY CHRISTINE C. PLASTOW Thesis submitted to University College London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy DEPARTMENT OF GREEK AND LATIN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON 1 DECLARATION I, Christine C. Plastow, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 ABSTRACT Homicide is a potent crime in any society, and classical Athens was no exception. The Athenians implemented legal methods for dealing with homicide that were set apart from the rest of their legal system, including separate courts, long-established laws, and rigorous procedures. We have, however, limited extant sources on these issues, including only five speeches from trials for homicide. This has fomented debate regarding aspects of law and procedure, and rhetoric as it relates specifically to homicide has not been examined in detail. Here, I intend to examine how the nature of homicide and its prosecution at Athens may have affected rhetoric when discussing homicide in forensic oratory. First, I will establish what I will call the ideology of homicide at Athens: the set of beliefs and perceptions that are most commonly attached to homicide and its prosecution. Then, I will examine homicide rhetoric from three angles: religious pollution, which was believed to adhere to those who committed homicide; relevance, as speakers in the homicide courts were subject to particular restrictions in this regard; and motive and intent, related issues that appear frequently in rhetoric and, in some cases, define the nature of a homicide charge. -

Language and Law a Resource Book for Students

Language and Law A resource book for students Allan Durant and Janny H.C. Leung First published 2016 ISBN: 978-1-138-02558-5 (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-138-02557-8 (pbk) ISBN: 978-1-315-43625-8 (ebk) Chapter A5 Persuasion in Court (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) DOI: 10.4324/9781315436258-6 PERSUASION IN COURT 21 A5 PERSUASION IN COURT A5 In this unit, we introduce the topic of how advocates talk. We show how courtroom persuasion by lawyers is ‘rhetorical’ in the historical meaning of ‘rhetoric’, which combines eloquence with strategic patterns of reasoning and expected standards of proof. We conclude with an outline of moves and structures that together make up the advocacy involved in legal proceedings. This description serves as an introduction to closer analysis of linguistic techniques in the language of advocates in Unit B5. Legal advocacy Silver-tongued, probing eloquence by lawyers addressing the court is the familiar representation of a distinctive style of lawyer talk. This image of advocacy, however, is highly selective. It is also in some respects anachronistic. In English law, to take one example, jury trial has declined in frequency since the mid-nineteenth century fairly dramatically, despite its continuing popular endorsement as a democratising feature of the legal system (Zander 2015). Currently, less than 1 per cent of all criminal cases are tried before a jury; and access to jury trial in civil proceedings is restricted to a very small (and diminishing) number of causes of action. The reality of courtroom advocacy, where it occurs, is more one of strategic preparation, case management and variation in style adapted to hearings at different levels in the court hierarchy, rather than grand courtroom oratory. -

The DNA of an Argument: a Case Study in Legal Logos Colin Starger

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 99 Article 4 Issue 4 Summer Summer 2009 The DNA of an Argument: A Case Study in Legal Logos Colin Starger Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Colin Starger, The DNA of na Argument: A Case Study in Legal Logos, 99 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 1045 (2008-2009) This Criminal Law is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/09/9904-1045 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 99, No. 4 Copyright 0 2009 by Northwestern University, School of Law Printed in U.S.A. THE DNA OF AN ARGUMENT: A CASE STUDY IN LEGAL LOGOS COLIN STARGER* This Article develops a framework for analyzing legal argument through an in-depth case study of the debate over federal actions for postconviction DNA access. Building on the Aristotelian concept of logos, this Article maintains that the persuasive power of legal logic depends in part on the rhetorical characteristics of premises, inferences, and conclusions in legal proofs. After sketching a taxonomy that distinguishes between prototypical argument logoi (formal, empirical, narrative, and categorical), the Article applies its framework to parse the rhetorical dynamics at play in litigation over postconviction access to DNA evidence under 42 U.S.C. -

RECONSIDERING the EPIDEICTIC by JOSEPH

CONGRUENT AFFINITIES: RECONSIDERING THE EPIDEICTIC by JOSEPH WYATT GRIFFIN A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of English and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2017 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Joseph Wyatt Griffin Title: Congruent Affinities: Reconsidering the Epideictic This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of English by: John Gage Chairperson James Crosswhite Core Member Anne Laskaya Core Member Mary Jaeger Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Joseph Wyatt Griffin This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Joseph Wyatt Griffin Doctor of Philosophy Department of English June 2017 Title: Congruent Affinities: Reconsidering the Epideictic Aristotle's division of the "species" of rhetoric (deliberative, forensic, and epideictic) has served as a helpful taxonomy in historical accounts of rhetoric, but it has also produced undesirable effects. One such effect is that epideictic rhetoric has been interpreted historically as deficient, unimportant or merely ostentatious, while political or legal discourse retained a favored status in authentic civic life. This analysis argues that such an interpretation reduces contemporary attention to the crucial role that epideixis plays in modern discourse. As often interpreted, epideictic rhetoric contains at its heart a striving toward communal values and utopic ideals. Taking as its province the good/bad, the praiseworthy/derisible, it is a rhetorical form supremely attentive to what counts for audiences, cultures, and subcultures. -

Not Mere Rhetoric: on Wasting Or Claiming Your Legacy, Justice Scalia Marie Failinger Mitchell Hamline School of Law, [email protected]

Mitchell Hamline School of Law Mitchell Hamline Open Access Faculty Scholarship 2003 Not Mere Rhetoric: On Wasting or Claiming your Legacy, Justice Scalia Marie Failinger Mitchell Hamline School of Law, [email protected] Publication Information 34 University of Toledo Law Review 425 (2003) Repository Citation Failinger, Marie, "Not Mere Rhetoric: On Wasting or Claiming your Legacy, Justice Scalia" (2003). Faculty Scholarship. Paper 358. http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/facsch/358 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Not Mere Rhetoric: On Wasting or Claiming your Legacy, Justice Scalia Abstract The thesis of the article is that the Court’s enterprise is centered on preserving community through an ethics of warranted trust, and that Scalia’s rhetoric often rejects such an ethic. A modern democratic citizen, along with his whole community, instead finds himself in the situation of necessary trust in democratic institutions like the Supreme Court. The willingness of a political community ultimately to place its trust in authority is partially dependent on that authority’s commitment to, and skill at, creating a convincing argument. The practice of rhetoric recognizes the dynamics of a relation of trust: the rhetor must put his or her own character up for judgment, he or she must create a situation of warranted trust by doing the homework on the matter at hand which Aristotle labeled invention, and he or she must demonstrate respect for the personhood—sacredness, if you will—of those who constitute his audiences by paying attention to who they are and what matters to them. -

The Tyranny of Custom: Discovering Innovations in Forensic Rhetoric from Classical Athens to Anglo-Saxon England

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Fall 12-14-2017 The Tyranny of Custom: Discovering Innovations in Forensic Rhetoric from Classical Athens to Anglo-Saxon England Steven Sams Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Sams, Steven, "The Tyranny of Custom: Discovering Innovations in Forensic Rhetoric from Classical Athens to Anglo-Saxon England." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2017. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/187 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE TYRANNY OF CUSTOM: DISCOVERING INNOVATIONS IN FORENSIC RHETORIC FROM CLASSICAL ATHENS TO ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND by STEVEN M. SAMS Under the Direction of Elizabeth Burmester, PhD ABSTRACT Scholarship tells the story of the history of rhetoric whereby the study of rhetoric declines first in the “Silver Age of Rome,” then loses any bearings or progress during first the Patristic period of the formation of the early Christian Church in the third through fifth century CE, and undergoes a second decline during the Germanic invasions starting in the fifth century. My task is defining and recovering new sources for rhetoric to spark more creative and in-depth analysis of this period in the history of rhetoric. Rather than simply move through a bibliographical list chronologically, I narrow in on the evolution of rhetorical appeals at specific points in history when a shift in control and usage of such appeals can be perceived, as the focus moves from static or well-established sources to fluid peripheral centers. -

Forensic Rhetoric and Philosophical Discourse in Cicero's

Thought on Trial: Forensic rhetoric and philosophical discourse in Cicero’s De Finibus Katherine Brookshire Owensby Trinity College of Arts and Sciences Duke University April 13th, 2020 An honors thesis submitted to the Duke Classical Studies Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with distinction for a Bachelor of Arts in Classical Languages. Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………..…………1 Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………...….2 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………..3-6 The forensic, the philosophical, the truth…………………………..……………………..…...7-18 Epicureanism on trial: Juxtaposition and the ethos of the speaker in Book II ….…...………19-35 Stoicism on trial: Arguing against one’s own beliefs……………………………………...…36-53 Conclusion.……………………………………………………………………….…………..54-56 Bibliography………………………………………………………….……………………....57-58 Acknowledgements Simply put, I would not be where I am today in Classics if it were not for Dr. Gregson Davis. Over the past four years he has become a wonderful professor, mentor, and advisor to this project. Ever since my freshman year, he has taught me to read Latin not necessarily quickly but rather, deeply. I plan to carry his close reading approach forward into my graduate studies and beyond. Professor Davis, I am so deeply grateful for all of your lessons, in and outside the classroom. It has been a pleasure to be your student, and I hope you have a wonderful retirement. Thank you also to Dr. Sander Evers, my former archaeological dig director. Though I quickly learned that I prefer reading in a library to digging under the hot Italian sun, I could not be more thankful for our conversations about Roman history and being a Classicist. Indeed, almost two years ago now you helped me first formulate the idea that would eventually become this project. -

Introduction to Classical Legal Rhetoric: a Lost Heritage

INTRODUCTION TO CLASSICAL LEGAL RHETORIC: A LOST HERITAGE MICHAEL FROST* A subject, which has exhausted the genius of Aristotle, Cicero, and Quinctilian [sic], can neither require nor admit much additional illustration. To select, combine, and apply theirprecepts, is the only duty left for their followers of all succeeding times, and to obtain a perfect familiarity with their instructions is to arrive at the mastery of the art.** John Quincy Adams, Boylston Professor of Rhetoric & Oratory, Harvard University In 400 A.D. if an ordinary Roman citizen of the educated class had a legal dispute with another citizen, he usually argued his own case before other Roman citizens and did so without the advice or help of a lawyer. Even so, he analyzed and argued his case with a near-professional competence and thoroughness. In preparing his case, he first determined the proper forum for his argument and iden- tifed the applicable law. He then determined which facts were most important, which legal arguments were meritorious, and which argu- ments his adversary might use against him. When choosing his strate- gies for the trial, he also decided how he would begin, tell the story of the case, organize his arguments, rebut his opponent, and close his case. Before actually presenting his arguments, he would carefully evaluate the emotional content of the case and the reputation of the judges. And finally, he would assess how his own character and credi- bility might affect the judges' responses to his legal arguments. In effect, he was analyzing and preparing his case in a lawyerly fashion. -

Aristotle the Art of Rhetoric

Aristotle The Art of Rhetoric Aristotle The Art of Rhetoric 1 Aristotle The Art of Rhetoric Translation and index by W. Rhys Roberts Megaphone eBooks 2008 Aristotle The Art of Rhetoric 2 BOOK I Aristotle The Art of Rhetoric 3 BOOK I Part 1 Rhetoric is the counterpart of Dialectic. Both true constituents of the art: everything else is alike are concerned with such things as come, merely accessory. These writers, however, say more or less, within the general ken of all men nothing about enthymemes, which are the sub- and belong to no definite science. Accordingly all stance of rhetorical persuasion, but deal mainly men make use, more or less, of both; for to a with non-essentials. The arousing of prejudice, certain extent all men attempt to discuss state- pity, anger, and similar emotions has nothing to ments and to maintain them, to defend them- do with the essential facts, but is merely a person- selves and to attack others. Ordinary people do al appeal to the man who is judging the case. this either at random or through practice and Consequently if the rules for trials which are now from acquired habit. Both ways being possible, laid down some states — especially in well- the subject can plainly be handled systematically, governed states — were applied everywhere, such for it is possible to inquire the reason why some people would have nothing to say. All men, no speakers succeed through practice and others doubt, think that the laws should prescribe such spontaneously; and every one will at once agree rules, but some, as in the court of Areopagus, give that such an inquiry is the function of an art. -

Discovering Innovations in Forensic Rhetoric from Classical Athens to Anglo-Saxon England Steven Sams

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Fall 12-14-2017 The yT ranny of Custom: Discovering Innovations in Forensic Rhetoric from Classical Athens to Anglo-Saxon England Steven Sams Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Sams, Steven, "The yT ranny of Custom: Discovering Innovations in Forensic Rhetoric from Classical Athens to Anglo-Saxon England." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2017. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/187 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE TYRANNY OF CUSTOM: DISCOVERING INNOVATIONS IN FORENSIC RHETORIC FROM CLASSICAL ATHENS TO ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND by STEVEN M. SAMS Under the Direction of Elizabeth Burmester, PhD ABSTRACT Scholarship tells the story of the history of rhetoric whereby the study of rhetoric declines first in the “Silver Age of Rome,” then loses any bearings or progress during first the Patristic period of the formation of the early Christian Church in the third through fifth century CE, and undergoes a second decline during the Germanic invasions starting in the fifth century. My task is defining and recovering new sources for rhetoric to spark more creative and in-depth analysis of this period in the history of rhetoric.