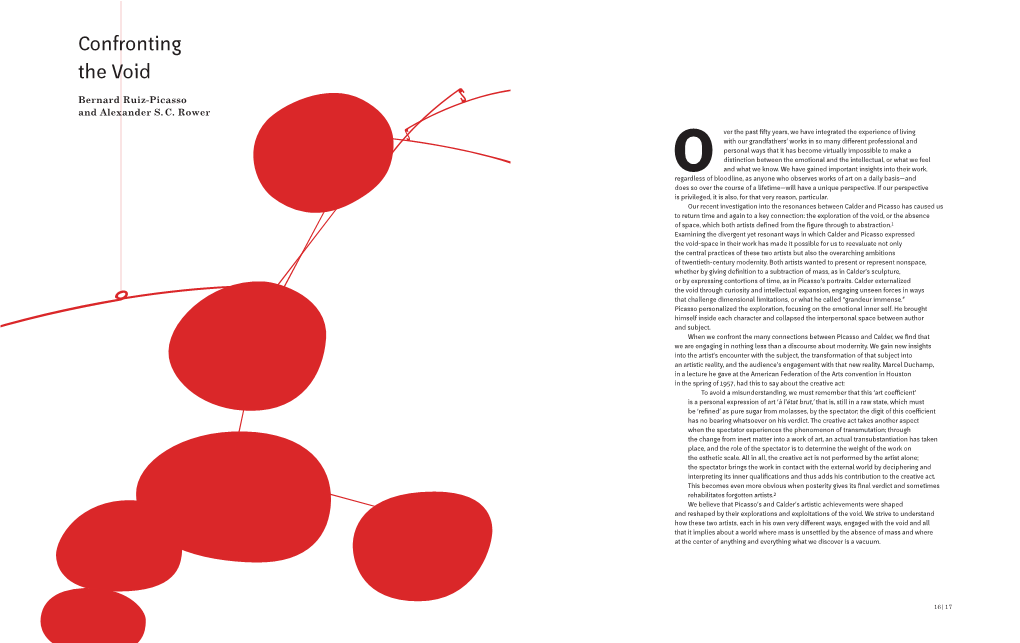

Confronting the Void

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dossier De Presse Expo CAPE Art Naïf

EXPOSITIONEXPOSITION D’ARTD’ART NAÏFNAÏF 11erer AVRILAVRIL -- 3131 MAIMAI 20142014 ESTEVILLEESTEVILLE « Le Génie des Modestes » Exposition de 50 chefs d’œuvre d’Art Naïf et populaire de la Collection Anatole Jakovsky de Blainville-Crevon au Centre abbé Pierre - Emmaüs Esteville - Normandie du 1er avril au 31 mai 2014 Centre d'étude et de documentation Anatole Jakovsky-Frère Moulin Pican route de Ry 76116 Blainville Crevon 02.35.80.49.15 [email protected] www.lasirene76.com Le lieu de mémoire de l’abbé Pierre propose de découvrir l’histoire et le message de l’abbé Pierre ainsi que les actions du Mouvement Emmaüs en France et dans le monde grâce à une scénographie moderne et sobre. Le Centre d’Esteville, situé à 30 km au nord de Rouen, est ouvert depuis le 22 janvier 2012. En plus de l’exposition permanente, il accueille une programmation culturelle riche et variée : conféren- ces, expositions, séminaires, animations, ateliers pédagogiques et concerts. En 2014, une exposition exceptionnelle d’œuvres d’Art naïf aura lieu au sein du Lieu de mémoire de l’abbé Pierre. Anatole Jakovsky est un critique d’art et un collectionneur pas- sionné d’Art naïf. Il a su reconnaître des talents et promouvoir des artistes tout au long de sa vie. La charmante bourgade de Blainville-Crevon, située à 20 km au nord de Rouen, a hérité d’une partie de sa très grande collection que les bénévoles de l’associa- tion La Sirène restaurent, cataloguent et mettent en valeur. 50 tableaux parmi les plus remarquables de la collection seront ex- posés du 1 er avril au 31 mai 2014 au Centre abbé Pierre - Emmaüs d’Esteville : Lucien Vieillard, Jean-François Crépin, Henry Dieck- mann, Isabelle de Jesus, Jules Lefranc, Gertrude O’Brady, Germain Vandersteen, Ivan Rabuzin, Bernard Vercruyce… Il s’agit d’un véri- table voyage dans l’univers de l’art naïf, art brut, art populaire, art non-conventionnel.. -

Nuit-Des-Musees-2019.Pdf

PROGRAMMATION Les de « LA CLASSE, L’ŒUVRE ! » LIEUX > En journée, entrée libre durant la manifestation « LA CLASSE, L’ŒUVRE ! » : partez à la découverte des œuvres des musées, guidés par les élèves, passeurs de culture. MUSÉE MATISSE MUSÉE DE PRÉHISTOIRE MUSÉE MATISSE MUSÉE DE LA En conclusion, les enfants aborderont l’avenir 164, avenue des Arènes de Cimiez DE TERRA AMATA des éléphants en sensibilisant le public à la Bus n° 15, 17, 20 - arrêt Arènes / Musée 18h [durée : 15 mn] PHOTOGRAPHIE 25, boulevard Carnot protection de la biodiversité. Matisse Bus n° 3, 7, 9, 10, 14, 81, 82 - arrêt Le Port Les Jeannettes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 CHARLES NÈGRE Michèle de Lorgeril et ses élèves de GS Bus n° 25 - arrêt Monastère Bus n° 20 et A30 - arrêt Lympia 14h à 15h 15h à 16h « Les Parmes », école maternelle Bellanda Bus n° 81, T32, 100 - arrêt Gustavin / Carnot présenteront leur création d’un livre L’Opéra du Monde, de Christine La mandibule en couleur e numérique devant les œuvres sculptées Les 6 3du collège Roland Garros abordent MUSÉE DE LA PHOTOGRAPHIE Spengler le thème de la mandibule de l’éléphanteau, Jeannettes I à V, 1910-1913 (au niveau 1). Les élèves de CM1-CM2 de l’école MUSÉE DES BEAUX-ARTS sous forme de dessins tout en couleur et de CHARLES NÈGRE Leurs travaux réalisés au cours de l’année Saint-Sylvestre s’inspireront des images de sculptures exposés dans la salle de 1, Place Pierre Gautier 33, avenue des Baumettes seront exposés à l’atelier pédagogique Christine Spengler pour les retranscrire sous conférences. -

Anatole Jakovsky (1907/1909? – 1983) : La Trajectoire D ’Un Critique D ’Art Au Xx E Siecle

UNIVERSITÉ PARIS IV-SORBONNE UFR D’ART ET D’ARCHÉOLOGIE MASTER I D’HISTOIRE DE L’ART Vanessa NOIZET SOUS LA DIRECTION DE Monsieur Arnauld PIERRE PROFESSEUR D’HISTOIRE DE L’ART CONTEMPORAIN Année universitaire 2010-2011 ANATOLE JAKOVSKY (1907/1909? – 1983) : LA TRAJECTOIRE D ’UN CRITIQUE D ’ART AU XX E SIECLE . Volume n°1 Vanessa Noizet 46, rue Gabriel Péri 94240 L’Haÿ-les-Roses [email protected] Session juin 2011 La trajectoire d’un critique d’art au XXe siècle. 1 La trajectoire d’un critique d’art au XXe siècle. SOMMAIRE Remerciements p. 5 Avertissement au lecteur p. 7 Avant-propos p. 8 Introduction p. 10 I. HISTOIRE DE L ’ABSTRACTION p. 17 1) L’historiographie de l’abstraction p. 18 « These-Antithese-Synthese » p. 20 Cubism and Abstract Art p.26 Une impasse picturale p. 26 2) Anatole Jakovsky et l’art britannique p. 29 Jean Hélion p. 29 Jean Hélion et l’art britannique p. 30 Hélion et Gallatin p. 31 Les contributions à Axis p. 32 II. REFLEXIONS SUR LA PEINTURE p. 34 1) Une extension du champ pictural p. 34 Condamnation de l’objet p. 34 L’espace du tableau p. 35 L’ « Art Mural » p. 37 2) Le cycle organique p. 38 III. MULTIPLES FACETTES D ’A NATOLE JAKOVSKY p. 41 1) Anatole Jakovsky, écrivain p. 41 2 La trajectoire d’un critique d’art au XXe siècle. 2) Anatole Jakovsky – Robert Delaunay : un intérêt pour les livres illustrés p. 44 Clefs des pavés p. 44 Vacances en Bretagne p. 46 3) Le collectionneur d’art abstrait p. -

Jeudi 16 Et Vendredi 17 Mai 2013 Paris Drouot

exp er t claude oterelo JEUDI 16 ET VENDREDI 17 MAI 2013 PARIS DROUOT JEUDI 16 MAI 2013 À 14H15 du n°1 au n°294 VENDREDI 17 MAI 2013 À 14H15 du n°296 au n°594 Exposition privée Etude Binoche et Giquello 5 rue La Boétie - 75008 Paris Lundi 13 mai 2013 de 11h à 18h et mardi 14 mai 2013 de 11h à 16h Tél . 01 47 42 78 01 Exposition publique à l’Hôtel Drouot Mercredi 15 mai 2013 de 11h à 18 heures Jeudi 16 et vendredi 17 mai 2013 de 11h à 12 heures Téléphone pendant l’exposition 01 48 00 20 09 PARIS - HÔTEL DROUOT - SALLE 9 COLLECTION D’UN HISTORIEN D’ART EUROPÉEN QUATRIÈME PARTIE ET À DIVERS IMPORTANT ENSEMBLE CONCERNANT VICTOR BRAUNER AVANT-GARDES DU XXE SIÈCLE ÉDITIONS ORIGINALES - LIVRES ILLUSTRÉS - REVUES MANUSCRITS - LETTRES AUTOGRAPHES PHOTOGRAPHIES - DESSINS - TABLEAUX Claude Oterelo Expert Membre de la Chambre Nationale des Experts Spécialisés 5, rue La Boétie - 75008 Paris Tél. : 06 84 36 35 39 [email protected] 5, rue La Boétie - 75008 Paris - tél. 33 (0)1 47 70 48 90 - fax. 33 (0) 1 47 42 87 55 [email protected] - www.binocheetgiquello.com Jean-Claude Binoche - Alexandre Giquello - Commissaires-priseurs judiciaires s.v.v. agrément n°2002 389 Commissaire-priseur habilité pour la vente : Alexandre Giquello Les lots 9 à 11 sont présentés par Antoine ROMAND - Tel. 06 07 14 40 49 - [email protected] 4 Jeudi 16 mai 2013 14h15 1. ARAGON Louis. TRAITÉ DU STYLE. Paris, Editions de la N.R.F., 1928. -

The Gardens of the Côte D’Azur

THE GARDENS OF THE CÔTE D’AZUR PRESS PACK Côte d’Azur Tourism CRT CÔTE D’AZUR – Tel. 33 (0)4 93 37 78 78 www.cotedazur-tourisme.com #CotedAzurNow PRESS CONTACT: International Press: Florence Lecointre [email protected] CONTENTS P. 5 80 public parks and gardens on the Côte d’Azur P. 7 New - Festival of the Gardens of the Côte d’Azur P. 11 Diary of Events P. 12 Address Book P. 15 Gardens and the Côte d’Azur, a long history P. 17 Scented Flowers in the Pays de Grasse P. 21 Private Gardens P. 24 “Jardins Remarquables” (Registered) P. 28 The Essential Gardens and Parks of the Côte d’Azur P. 36 The Gardens of the Stately Homes of the Côte d’Azur P. 38 The Gardens of the Châteaux of the Côte d’Azur P. 39 The Monastic Parks and Gardens of the Côte d’Azur P. 40 Museum Gardens P. 42 Hotel Gardens P. 45 The Unclassifiables P. 47 Routes 22 26 23 16 3 9 17 11 10 7 14 27 2 12 25 24 20 8 13 5 18 4 21 1 19 15 28 6 80 PUBLIC PARKS AND GARDENS ON THE CÔTE D’AZUR 1 ANTIBES Botanical Garden of the Villa Thuret 17 MONACO Exotic Garden Parc Explora Japanese Garden Garden of the Villa Eilen Roc The Rose Garden Garden of the Fort Carré Fontvieille Park 2 Garden of the Petite Afrique BEAULIEU Garden of the Villa Kérylos Garden St-Martin 3 BEAUSOLEIL The Winter Garden of the Riviera Palace 18 MOUANS-SARTOUX Garden of the Château de Mouans-Sartoux 4 BIOT Garden of the Fernand Léger Museum Gardens of the International Perfumery Museum The Bonzai Arboretum 19 MOUGINS The Fontmerle Pond 5 CAGNES-SUR-MER Renoir Estate 20 NICE Promenade du Paillon and -

Atelier Émilienne Delacroix

ATELIER ÉMILIENNE DELACROIX SALLE DES VENTES FAVART 1, rue Favart - 75002 Paris Remerciements A la fille de l’artiste Liliane Debernard dite Liliane Robert, accordéonniste populaire et jeune femme de 84 ans et A ses amis Laura Wallenstein David Cohen-solal Aux fidèles amis de l’artiste qui ne sont plus, dont Jacques Prévert et André Verdet A tous les collectionneurs du vivant de l’artiste, notamment Paul Roux, Auberge de la Colombe d’Or Aimé Maeght Nathan Cummings, Chicago(Fondation) Tyrone Power, Hollywood Ali Khan, Château de l’Horizon Pablo Picasso Jean Cocteau Juan Miró Suzy Solidor Réalisation catalogue : Laura Wallenstein VENTE EN SOIRÉE - NOUVELLE ADRESSE JEUDI 24 SEPTEMBRE 2009 - 18 HEURES 30 SALLE DES VENTES FAVART - 1, RUE FAVART - 75002 PARIS ENSEMBLE DE TABLEAUX d’éMILIENNE DELACROIX AFFICHES - LIVRES - DOCUMENTS - AUTOGRAPHES & GRAVURES - ESTAMPES Fernand LÉGER - Juan MIRÓ RARE LIVRE D’OR Dessins de Picasso, Miró, Cocteau ... Exposition publique à la salle des ventes FAVART, 1 rue Favart Du vendredi 18 septembre au jeudi 24 septembre de 9h30 à 18 h Téléphone pendant les expositions : 01 53 40 77 10 Photos et liste consultables sur www. ader-paris. fr Rémi ADER, David NORDMANN et Thomas TEIRLYNCK Commissaires-Priseurs habilités - SVV 2002-448 - 3, rue Favart, 75002 Paris www. ader-paris. fr - Tél. : 01 53 40 77 10 - Fax : 01 53 40 77 20 - contact@ader-paris. fr Quelques témoignages «C’était une matinée d’août. Emilienne Delacroix allait et venait, de l’atelier à la cuisine, de la cuisine à l’atelier. Les poêlons et le marmitons étaient sagement alignés sur le mur, les godets et les pinceaux sur la petite table de travail. -

The Following Is a List of Museums

MUSEUMS WITH INTEREST IN TOBACCO Compiled by Ben Rapaport (Fall 2006) The following is a list of museums (and other places) around the globe having a few...to many tobacco-related relics, artifacts, and antiques, based on research to date. I do not guarantee that (1) the museum is still open to the public or (2) items once cited as "tobacco" are still current holdings. Where specific information has been provided to me by the museum's curator or by visitors, I have noted the holdings. For German museums, I have extracted Billerbeck, Mit Rauchern lässt sich reden, published in 1993, a book that surveys German museums emphasizing tobacco-related artifacts. In many cases, the address is not complete, so if you have corrections (or additions), I would certainly appreciate your input. Keep this list and I hope it proves useful in your global travels. AUSTRALIA Sydney NSW1238 Powerhouse Museum, 500 Harris Street Ultimo, PO Box K346 Haymarket AUSTRIA 8911 Admont: Heimatmuseum, Garbenteichring 325 6861 Alberschwende: Heimatmuseum, Neues Arzthaus 6235 Alpach: Bergbauernmuseum, Unterberg 34 8671 Alpl: Österreichisches Wundermuseum, Alpl 45 3300 Amstetten: Bauernmuseum, Gigerreith 30 2151 Asparn an der Zaya: Weinlandmuseum, Asparn 240 4822 Bad Goisern: Heimatmuseum, Bad Goisern 725 4540 Bad Hall: Heimathaus Bad Hall 6900 Bregenz: Vorarlberger Landesmuseum, Kornmarkt 1 7000 Eisenstadt: Burgenländisches Landesmuseum, Museumgasse 1-5 4240 Freistadt: Heimathaus 4210 Gallneukirchen: Afrika-Museum, Marianhiller Missionhaus 4810 Gmunden: Kammerhofmuseum, -

Practical Guide

PRACTICAL GUIDE NP 1 CONTENTS Page 01 GETTING AROUND NICE 2 • BY BUS • BY TRAMWAY • VÉLO BLEU (BICYCLE RENTAL) • VOITURE BLEUE • BY TAXI Page 02 SIGHTS & MONUMENTS 07 LABELS • OLD CITY 19 4 • DOWNTOWN • THE PORT • HILLS 20 08 CITY CENTER MAP 03 PARKS & GARDENS 09 AROUND NICE 8 • LEISURE PARKS 22 • SKI RESORTS • ANIMAL PARKS • MERCANTOUR NATIONAL PARK 04 CULTURE 10 THE FRENCH RIVIERA 10 • MUSEUMS 23 • BY TRAIN • GALLERIES • BY BUS • OTHER EXHIBITION VENUES • BY MINI BUS 05 GUIDED TOURS 11 NICE CÔTE D’AZUR 14 • WALKING TOURS 24 METROPOLITAN MAP • BY BIKE • BY BOAT 12 PRACTICAL INFORMATION 06 ACTIVITIES & LEISURE 25 18 • BEACHES • WATER SPORTS • OTHER ACTIVITIES > Booking in the Nice Convention and Visitors Bureau and on nicetourisme.com > Included in the French Riviera Pass A > City center reference 2 3 20.06.2018 09:56 (tx_vecto) PDF_1.3_PDFX_1a_2001 300dpi YMCK ISOcoated_v2_300_eci CONTENTS Page 01 GETTING AROUND NICE 2 • BY BUS • BY TRAMWAY • VÉLO BLEU (BICYCLE RENTAL) • VOITURE BLEUE • BY TAXI Page 02 SIGHTS & MONUMENTS 07 LABELS • OLD CITY 19 4 • DOWNTOWN • THE PORT • HILLS 20 08 CITY CENTER MAP 03 PARKS & GARDENS 09 AROUND NICE 8 • LEISURE PARKS 22 • SKI RESORTS • ANIMAL PARKS • MERCANTOUR NATIONAL PARK 04 CULTURE 10 THE FRENCH RIVIERA 10 • MUSEUMS 23 • BY TRAIN • GALLERIES • BY BUS • OTHER EXHIBITION VENUES • BY MINI BUS 05 GUIDED TOURS 11 NICE CÔTE D’AZUR 14 • WALKING TOURS 24 METROPOLITAN MAP • BY BIKE • BY BOAT 12 PRACTICAL INFORMATION 06 ACTIVITIES & LEISURE 25 18 • BEACHES • WATER SPORTS • OTHER ACTIVITIES > Booking in the Nice Convention and Visitors Bureau and on nicetourisme.com > Included in the French Riviera Pass A > City center reference 2 3 20.06.2018 09:56 (tx_vecto) PDF_1.3_PDFX_1a_2001 300dpi YMCK ISOcoated_v2_300_eci 01 GETTING AROUND NICE BY TRAMWAY LIGNES D’AZUR AGENCIES: 08 1006 1006 (Service 0,06 €/min + price of a local call) Réservez votre prochain séjour www.lignesdazur.com AUTO BLEUE sur la Côte d’Azur avec You must stamp your ticket every time you board the tram. -

Emanuel Proweller Proweller, Toujours 18/81/18

Emanuel Proweller Proweller, toujours 18/81/18 Galerie Convergences 2018 1 ATELIE R R E E L M L E A N W U O E R L P 2 Proweller, toujours 18/81/18 Galerie Convergences 2018 3 PROWELLER, PEINTRE INVISIBLE Depuis que l’art vivant a déployé ses sicaires, contempteurs à six coups ou ses admirateurs dociles, il est un fait acquis que tout artiste doit disposer de son propre ADN, une personnalité suffisamment éloquente pour qu’on le range dans telle ou telle catégorie, comme les poissons du chalutier juste pêchés, tirés du filet, accueillis dans tel ou tel casier de couleurs différentes. Poissons brillants, acidulés, poissons remuants, petits ou gros : avec quelle maille, dans quelle catégorie les placer ? Les chalands aiment les étals rutilants embellis d’une ordonnance cohérente. Cela rassure, particulièrement dans les salles de musées. Emanuel Proweller, malgré sa modestie, est devenu un gros poisson, cela bien après sa disparition en 1981. On chercherait vainement quelle marée l’a porté jusqu’à nous. Son univers entre collorisme franc et mezzo et avec volumes découpés à vif, entre informel et réel, reste étrange. Les subtils ajustements, les conjonctions de domaines antagonistes composent un environnement à part, avec un agrégat de sens, avec des interstices, des passages secrets. Comme un cluster, une physique délicate. Comme beaucoup – et le silence assourdissant de quelques dizaines d’années concernant Proweller en témoigne – c’est un peintre que nous avons peu ou mal regardé. Comme si son côté mouton à cinq pattes ne pouvait satisfaire la raison esthétique, rassurer les clans. -

From Constable to Koons Books Inscribed by Artists

From Constable to Koons Books Inscribed by Artists Benjamin Spademan Rare Books The descriptions in the catalogue are brief. Fuller descriptions are available on request. FROM CONSTABLE TO KOONS All the books are in fine condition, unless otherwise stated. The reproductions are not the actual size. BOOKS INSCRIBED BY ARTISTS Benjamin Spademan Rare Books 14 Mason’s Yard, London SW1Y 6BU + 44 (0)7768 076772 [email protected] www.benjaminspademan.com Cover Henri Matisse. Verve, Revue artistique et littéraire, n° 66. Title page D. G. Rossetti. A Treasure of English Sonnets, n° 82. BENJAMIN SPADEMAN RARE BOOKS I started putting together this group of books, almost by chance some ten years ago, when I acquired in Paris a monograph on Henry Moore, with an original drawing and presentation by the artist on the title page. Next came a Francis Bacon, and thereafter gradually a collection began to form. To qualify for inclusion, books had to have been personally transformed by the artist, usually as a gift to another person. The criteria for selection were drawn broadly, to include visual artists of all kinds - painters, sculptors, illustrators, cartoonists, stage & fashion designers - and allowing all kinds of art, from highly finished drawings, collages and watercolours to fairly minimal interventions. The books too covered a wide range of types, from livres d’artistes, to standard monographs, to periodicals, exhibition catalogues and ephemera such as invitations. In the process of selection, the focus was always on the quality of the image and the interest of the inscription.The earliest examples, John Constable and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, are both intensely personal family affairs. -

Alexander Calder Mobile, C. 1937 Pablo Picasso Figure

CALDER– PICASSO Back cover Front cover Cat. A Alexander Calder Arnold Newman Mobile, c. 1937 Alexander Calder in his Roxbury studio, January 3, 1957 Pablo Picasso Figure (projet pour un monument Cat. B à Guillaume Apollinaire) Arnold Newman [Figure (Project for a Monument Pablo Picasso in the Fournas studio, to Guillaume Apollinaire)], Fall 1928 Vallauris, June 2, 1954 This book is published EXHIBITION CATALOG Project Manager We sincerely thank the partner MUSEO PICASSO MÁLAGA Our sincere thanks go WHITNEY MUSEUM The Musée national Picasso-Paris Virginie Perdrisot-Cassan, Curator, Cheikh Tidiane Diallo, Financial on the occasion of the exhibition Sophie Ratajczak institutions of this exhibition the museums, institutions, OF AMERICAN ART, NEW YORK is a public establishment Collections Manager for Paintings Manager Concept and Scientific Direction Artistic Director ”Calder-Picasso“ organized for their scientific contributions and collectors who have of administrative nature created (1922–1937), Sculptures and Claire Garnier José Lebrero Stals Director Jennifer Duhamel, Apprentice in partnership with the Calder Research Assistants and the outstanding loans they participated in this exhibition by the Decree no. 2010-669 Giacometti’s Furniture Émilia Philippot Adam D. Weinberg Foundation and the Fundación Mariah Coulibaly have granted: through generous loans. of June 18, 2010. Florent Lamare, Head of Financial Alexander S. C. Rower Financial Manager Émilia Philippot, Chief Curator, Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso Simona Dvorakova It is placed -

The Following Is a List of Museums (And Other Places) Around the Globe Having a Few

MUSEUMS WITH HOLDINGS OF TOBACCO-RELATED ARTIFACTS Compiled by Ben Rapaport (Winter, 2018-2019) The following is a list of museums (and other places) around the globe having a few ... or many tobacco-related relics, artifacts, and antiques. I do not guarantee that (1) the museum is still open to the public or (2) items once cited as "tobacco" are still current holdings. Where specific information has been provided to me by the museum's curator or by visitors, I have noted the holdings. For German museums, I have used Billerbeck, Mit Rauchern lässt sich redden (1993) and Franz Wandinger, “Rauchzeichen in Deutschen Museen,” Teil 1 (Knasterkopf, Heft 14, 2001 and Teil 2, Band 15, 2002). Both sources identify and describe German museums that have any segment of tobacco or tobacco-related artifacts. In some instances, the museum address is not complete, so if you have corrections (or additions), I would appreciate your input. I hope this list proves useful in your global travels or at-home research. Bear in mind that, occasionally, museums open and close without much public fanfare, and others relocate quite often, so this edition may not be wholly up-to-date. Check the Web or contact the museum before you plan a visit and to determine whether the artifacts you desire to see are on permanent display or in storage, and if you require a special appointment. To those researchers interested wholly in clay tobacco pipes, note the following related links: (1) the online article, S. D. White, ‘Chapter 3: Methodology’ in The Dynamics of Regionalisation and Trade: Yorkshire Clay Tobacco Pipes c 1600-1800, in Peter Davey and David A.