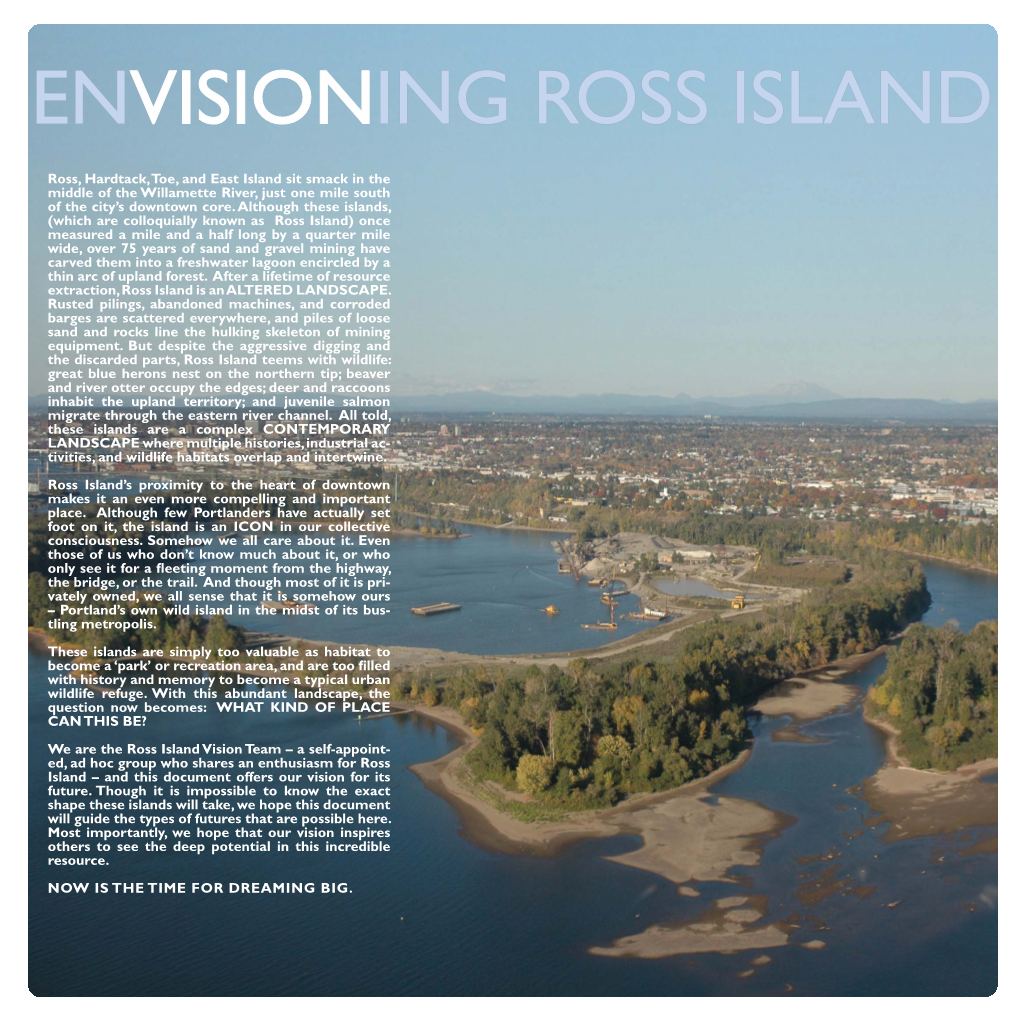

A Visionary Plan for Ross Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF File Parks Capital and Planning Investments

SWNI Commissioner Amanda Fritz Interim Director Kia Selley INVESTMENTS IN SOUTHWEST NEIGHBORHOODS, INC. ANNOUNCED 2013-2018 August 2018 | Since 2013, Commissioner Amanda Fritz and Portland Parks & Recreation (PP&R) have allocated over $38M in park planning and capital investments in the Southwest Neighborhoods, Inc. coalition area. Funded by System Development Charges (SDCs), the Parks Replacement Bond (Bond), General Fund (GF), and in some cases matched by other partners, these investments grow, improve access to, or help maintain PP&R parks, facilities, and trails. Questions? Please call Jennifer Yocom at 503-823-5592. CAPITAL PROJECTS, ACQUISITIONS & PLANNING #1 APRIL HILL PARK BOARDWALK AND TRAIL Completed: Winter 2017 Investment: $635K ($498K SDCs; $83K Metro; $25K neighborhood #5 PORTLAND fundraising; $19K PP&R Land Stewardship; $10K BES) OPEN SPACE SEQUENCE Info: New boardwalks, bridges, trails; improves access, protects wetland. #2 DUNIWAY (TRACK & FIELD) #2 DUNIWAY PARK TRACK & FIELD DONATION #4 MARQUAM, #8 SOUTH Completed: Fall 2017 TERWILLIGER, WATERFRONT GEORGE HIMES Investment: Donation of full renovations provided by Under Armour (ACQUISITION & Info: Artificial turf improvement and track re-surfacing. RESTORATION) #3 MARSHALL PARK PLAYGROUND & ACQUISITION Completed: Summer 2015 | 2018 Investment: $977K (Play Area - $402K [$144K OPRD, $257K SDCs] + #11 RIEKE (FIELD) Acquisition - $575K [$450K SDCs, $125K Metro Local Share]) #6 Info: Playground, access to nature and seating improvements | two- #12 GABRIEL RED #9 WILLAMETTE -

FY 2018-19 Requested Budget

Portland Bureau of Transportation FY 2018-19 Requested Budget TABLE OF CONTENTS Commissioner’s Transmittal Letter Bureau Budget Advisory Committee (BBAC) Report Portland Bureau of Transportation Organization Chart Bureau Summary Capital Budget Programs Administration and Support Capital Improvements Maintenance Operations Performance Measures Summary of Bureau Budget CIP Summary FTE Summary Appendix Fund Summaries Capital Improvement Plan Summaries Decision Package Summary Transportation Operating Fund Financial Forecast Parking Facilities Fund Financial Forecast Budget Equity Assessment Tool FY 2018-19 to FY 2022-23 CIP List Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 Dear Transportation Commissioner Saltzman, Mayor Wheeler, and Commissioners Eudaly, Fish, and Fritz: The PBOT Budget/Bureau Advisory Committee (BBAC) is a collection of individuals representing a range of interests impacted by transportation decisions, including neighborhoods, businesses, labor, bicyclists and pedestrians, and traditionally underserved communities. We serve on the BBAC as volunteers who have our city’s best interests in mind. With helpful support from the Director and her staff, we have spent many hours over the last five months reviewing the Bureau’s obligations and deliberating over its budget and strategy priorities. Together we have arrived at the following recommendations. Investment Strategy: The Bureau’s proposed Investment Strategy prioritizes funding projects that address three primary concerns: maintaining existing assets, managing for growth, and advancing safety. Underlying the selection and evaluation process is the Bureau’s laudable focus on equity. We support the adoption of this “triple-win” strategy. We are pleased to see safety and equity as top priorities of the Director and her staff. The City has been allocated transportation funding as a result of the Oregon Legislature passing the historic Oregon Transportation Package in House Bill 2017. -

Portland City Council Agenda

CITY OF OFFICIAL PORTLAND, OREGON MINUTES A REGULAR MEETING OF THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF PORTLAND, OREGON WAS HELD THIS 4TH DAY OF FEBRUARY, 2015 AT 9:30 A.M. THOSE PRESENT WERE: Mayor Hales, Presiding; Commissioners Fish, Fritz, Novick and Saltzman, 5. Commissioner Saltzman arrived at 9:33 a.m. OFFICERS IN ATTENDANCE: Karla Moore-Love, Clerk of the Council; Linly Rees, Deputy City Attorney; and Jim Wood, Sergeant at Arms. Item Nos. 130 and 132 were pulled for discussion and on a Y-5 roll call, the balance of the Consent Agenda was adopted. Disposition: COMMUNICATIONS 124 Request of Ibrahim Mubarak to address Council regarding houseless issues (Communication) PLACED ON FILE 125 Request of Mary Ann Schwab to address Council regarding Mt. Tabor Reservoir disconnect public involvement processes (Communication) PLACED ON FILE 126 Request of David Kif Davis to address Council regarding police targeting of journalists and photo journalists during Ferguson Solidarity March (Communication) PLACED ON FILE 127 Request of Joe Walsh to address Council regarding scheduling a communication (Communication) PLACED ON FILE 128 Request of Michael Withey to address Council regarding update on micro communities, Accessory Dwelling Units and tiny houses (Communication) PLACED ON FILE TIMES CERTAIN 129 TIME CERTAIN: 9:30 AM – Proclaim the month of February 2015 to be Black History Month in Portland (Proclamation introduced by Mayor Hales) 15 minutes requested PLACED ON FILE CONSENT AGENDA – NO DISCUSSION 1 of 147 February 4, 2015 130 Authorize City Attorney to seek and appeal a limited judgment in Anderson v. City of Portland, Multnomah Circuit Court No. -

STUDY AREA AMENITIES NAITO MADISON 14TH Inner Southeast Portland MADISON 13TH

MAIN HAWTHORNE Legend STUDY AREA AMENITIES NAITO MADISON 14TH inner southeast portland MADISON 13TH 15TH 17TH N 18TH 19TH 20TH urban design 16TH HAWTHORNE Commercial/Retail Eastside Streetcar (2012) 22ND 2ND This section of Inner Southeast Portland 3RD 7TH 10TH CLAY 11TH encompasses a broad mix of uses, transportation 16TH corridors, and geographic contexts. Along the MAPLE HOLLY Willamette riverfront runs a section of the GRAND I5 MARKET Eastbank Esplanade PCC Training Center Eastbank Esplanade multi-use trail, docks for ELLIOTT MARKET POPLARrecreational and commercial boaters, OMSI’s MILL MARTIN LUTHER KING JR HAZELsubmarine pier, and heavy industrial use at the Ross Island Sand & Gravel terminal. Commercial MULBERRY PALM Goodwill Industries uses near Hawthorne comprise numerous STEPHENS wholesalers of constructionSTEPHENS and 22ND home- finisheing goods. Further into the heart of the 16TH LOCUST district, construction suppliers, Northwest HARRISON Natrual Gas, and DariGold all21ST maintain large Realigned MLK Viaduct (2011) HARRISON facilities. Residential uses are non-existent and 12TH HARRISON HARRISON 5 OMSI LARCH retail is only present along small stretches of SE HALL LINCOLN Oregon Rail Heritage Foundation 12th Ave andHEMLOCK Woodward/Powell. OMSI and Portland Opera WATER Development (future) CYPRESS Development (future) LINCOLN RIVER 20TH DIVISION GRANT 16TH Portland Opera GRANT BIRCH SHERMAN SPRUCE LADD LAVENDER OMSI Station (2015) TAMARACK SHERMAN OHSU Schnitzer Campus (future) CARUTHERS CARUTHERS -

2015 DRAFT Park SDC Capital Plan 150412.Xlsx

2015 PARK SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT CHARGE 20‐YEAR CAPITAL PLAN (SUMMARY) April 2015 As required by ORS 223.309 Portland Parks and Recreation maintains a list of capacity increasing projects intended to TYPES OF PROJECTS THAT INCREASE CAPACITY: address the need created by growth. These projects are eligible to be funding with Park SDC revenue . The total value of Land acquisition projects summarized below exceeds the potential revenue of $552 million estimated by the 2015 Park SDC Methodology and Develop new parks on new land the funding from non-SDC revenue targeted for growth projects. Expand existing recreation facilities, trails, play areas, picnic areas, etc The project list and capital plan is a "living" document that, per ORS 223.309 (2), maybe modified at anytime. It should be Increase playability, durability and life of facilities noted that potential modifications to the project list will not impact the fee since the fee is not based on the project list, but Develop and improve parks to withstand more intense and extended use rather the level of service established by the adopted Park SDC Methodology. Construct new or expand existing community centers, aquatic facilities, and maintenance facilities Increase capacity of existing community centers, aquatic facilities, and maintenance facilities ELIGIBLE PROJECTS POTENTIAL REVENUE TOTAL PARK SDC ELIGIBLE CAPACITY INCREASING PROJECTS 20‐year Total SDC REVENUE CATEGORY SDC Funds Other Revenue Total 2015‐35 TOTAL Park SDC Eligible City‐Wide Capacity Increasing Projects 566,640,621 City‐Wide -

RECONNAISSANCE REPORT Operational Feasibility Study: Task 2

RECONNAISSANCE REPORT Operational Feasibility Study: Task 2 I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 1 A. PURPOSE .................................................................................................................................. 1 II. METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................ 1 A. PLANNING ................................................................................................................................. 1 B. CONDUCT OF RECONNAISSANCE ........................................................................................... 1 C. MERGING DATA ........................................................................................................................ 2 III. OBSERVATIONS ........................................................................................................................... 2 A. ROUTE ASSESSMENT .............................................................................................................. 2 1. ROUTE DESCRIPTION .......................................................................................................... 2 2. GENERAL .............................................................................................................................. 4 3. BY ROUTE LEG .................................................................................................................... -

Ross Island Bridge Rehabilitation Project Frequently Asked Questions

Ross Island Bridge Rehabilitation Project Frequently Asked Questions What does the project involve? Starting in October 2014, contractors will remove about 250 deteriorating rivets and upgrade the steels members. This first phase will take six to eight weeks to complete. In the spring of 2015, crews will begin preparations to paint the bridge. This involves stripping old paint down to the bare steel, treating the bare steel for rust and then applying the new paint. Why paint the Ross Island Bridge? The paint on the U.S. 26 Willamette River Bridge (Ross Island Bridge) has deteriorated and no longer provides the necessary corrosion protection and aesthetic appearance. The bridge was last painted in 1967. This work will preserve its structural integrity and help extend its useful life. Why do the rivets need to be removed? Many of the rivets haven’t been replaced since the bridge opened in 1926 and are being removed because of rust and corrosion. Removing and replacing the rivets will help strengthen the bridge, preserve its structural stability and extend its service life. What’s the schedule? Rivet removal will take place in the fall of 2014 and will require six to eight weeks to complete. The painting will take place in the dry season, spring to fall, in 2015, 2016 and 2017. The project is scheduled for completion in late 2017, although the schedule is subject to change due to weather and site conditions. What are the work hours? The rivet work will occur during the day between 7 a.m. and 6 p.m. -

2020 Reciprocal Admissions Program

AMERICAN HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY 2020 RECIPROCAL ADMISSIONS PROGRAM Participating Gardens, Arboreta, and Conservatories For details on benefits and 90-mile radius enforcement, see https://ahsgardening.org/gardening-programs/rap Program Guidelines: A current membership card from the American Horticultural Society (AHS) or a participating RAP garden entitles the visitor to special admissions privileges and/or discounts at many different types of gardens. The AHS provides the following guidelines to its members and the members of participating gardens for enjoying their RAP benefits: This printable document is a listing of all sites that participate in the American Horticultural Society’s Reciprocal Admissions Program. This listing does not include information about the benefit(s) that each site offers. For details on benefits and enforcement of the 90- mile radius exclusion, see https://ahsgardening.org/gardening-programs/rap Call the garden you would like to visit ahead of time. Some gardens have exclusions for special events, for visitors who live within 90 miles of the garden, etc. Each garden has its own unique admissions policy, RAP benefits, and hours of operations. Calling ahead ensures that you get the most up to date information. Present your current membership card to receive the RAP benefit(s) for that garden. Each card will only admit the individual(s) whose name is listed on the card. In the case of a family, couple, or household membership card that does not list names, the garden must extend the benefit(s) to at least two of the members. Beyond this, gardens will refer to their own policies regarding household/family memberships. -

1. Demonstration Project Description

1. Demonstration Project Description Introduction The Lake Oswego to Portland Trail is an opportunity like no other in the Portland Region. This project follows the Willamette River, a natural treasure of statewide significance, and connects neighborhood redevelopment projects in downtown Lake Oswego’s Foothills District and Portland’s South Waterfront and Johns Landing districts. Both the City of Portland and the City of Lake Oswego have extensive trail systems, and this Active Transportation Corridor provides the critical regional connection between them. It passes Tryon Creek State Park and several local parks with recreational and natural restoration opportunities. Perhaps most significantly, there is no existing bicycle and pedestrian facility along much of the corridor. This project can implement much needed safety improvements and provide additional travel options along the constrained Highway 43 corridor. With three significant transportation projects currently under development in the corridor, including a new gateway into the South Waterfront District, a new Sellwood Bridge, and a streetcar transit connection, the time is right to build this trail. The Need for this Active Transportation Corridor • Safety: There is no existing bicycle and pedestrian facility along the Highway 43 corridor south of the Sellwood Bridge. This state highway has a posted 45‐mph speed limit, few sidewalks, and substandard, inadequate shoulders. • Leverage future transit: With a potential streetcar extension along this corridor, this project will provide essential bicycle and pedestrian connections to stop locations. • Economic Development: Current planning efforts in Portland’s South Waterfront and Johns Landing districts and Lake Oswego’s Foothills District will be greatly enhanced with improved bicycle and pedestrian facilities. -

Park Tree Inventory Findings

Tree Summit 2019 PORTLANDPARKS.ORG | Commissioner Nick Fish | Director Adena Long PORTLANDPARKS.ORG | Commissioner Nick Fish | Director Adena Long Agenda 9:00am – 9:10am Welcome Jeff Ramsey, Science and Policy Specialist, PP&R Urban Forestry 9:15 am – 10:00 am Results from Portland’s First Inventory of Neighborhood Park Trees Bryn Davis and Bianca Dolan, PP&R Urban Forestry 10:05 am – 10:20 am Canaries in the Coal Mine: Studying urban trees reveals climate impacts on native forests Aaron Ramirez, Professor of Biology, Reed College 10:25 am – 10:40 am Thuja plicata, Hakuna Matata? The Mystery of Western Redcedar Decline in the Pacific Northwest Christine Buhl, Forest Entomologist, Oregon Department of Forestry 10:45 am – 11:00 am Break 11:00 am – 11:15 am Art and Activism in the Urban Forest: The Tree Emergency Response Team Ashley Meyer, Elisabeth Art Center 11:15 am – 11:30 am Film Screening: 82nd and Verdant Filmmaker James Krzmarzick and Dave Hedberg of the Canopy Stories Film Project 11:35 am – 11:45 am Bill Naito Community Trees Award Ceremony Jenn Cairo, City Forester, PP&R Urban Forestry 11:50 am – Noon Growing Portland’s Future Forest Together Angie DiSalvo, Science and Outreach Supervisor, PP&R Urban Forestry Noon – 1:00pm LunchPORTLANDPARKS.ORG and Breakout | Commissioner Session Nick Fish | Director Adena Long Hamilton Park PORTLANDPARKS.ORG | Commissioner Nick Fish | Director Adena Long PORTLANDPARKS.ORG | Commissioner Nick Fish | Director Adena Long Alberta Park PORTLANDPARKS.ORG | Commissioner Nick Fish | Director Adena -

Greenspaces Accomplishment Report

metropolitan Greenspaces program Summary of Accomplishments 1991-2005 Metro U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Regional Parks and Greenspaces Oregon Fish and Wildlife Office 600 NE Grand Avenue 2600 SE 98th Avenue, Ste. 100 Portland, Oregon 97232 Portland, Oregon 97266 (503) 797-1850 (503) 231-6179 January 2005 Table of Contents PURPOSE OF THIS REPORT ...................................................................................................... 2 METROPOLITAN GREENSPACES PROGRAM OVERVIEW ................................................. 2 PUBLICATIONS, PRODUCTS and GREENSPACES PROJECTS ............................................ 4 CONSERVATION AND RESTORATION GRANT PROJECTS ............................................... 7 ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION GRANT PROJECTS ........................................................ 32 SALMONID EDUCATION AND ENHANCEMENT GRANT PROJECTS ............................ 57 GREEN CITY DATA PROJECT ................................................................................................ 64 Authors: This report was written by Ron Klein, Mel Huie, Lynn Wilson, Deb Scrivens and Ilene Moss of Metro Regional Parks and Greenspaces and Jennifer Thompson with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Oregon Fish and Wildlife Office. Contacts: Kemper McMaster, State Supervisor Jennifer Thompson, Greenspaces Program Coordinator U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Oregon Fish and Wildlife Office 2600 SE 98th Avenue, Ste. 100 Portland, Oregon 97266 (503) 231-6179 Jim Desmond, Director Metro Regional Parks & Greenspaces 600 -

Reserve a Park for Your Picnic

Reserve a Park for Your Picnic Making reservations, policies, insurance, and more Prices and policies within are valid for permits booked from February 18 - June 30, 2020. GENERAL INFORMATION Picnic permits allow you to bring in the following items Portland Parks & Recreation (PP&R) has 200+ parks and for your event - gardens, and many of these locations have individual • 1-2 tables and/or 1-2 pop-up canopies (no larger picnic tables available for use on a first-come, first-served than 10’x10’, no stakes are allowed in a park) basis. When there is a grouping of three or more tables, • a residential-style barbecue grill they are often reservable. To guarantee your picnic • small speakers heard only within immediate date and location, it is recommended that you make a picnic area picnic reservation in advance. For your convenience, this Special Use Permits are required when - brochure lists picnic sites and fees. Parks not included in • there is BYOB beer and wine present and more than 49 this brochure may be reserved under a Special Use Permit. people of any age • you’d like to provide alcohol (hosted, catered, kegs, etc.) Picnic permits cover the following type of events - • you’d like to bring items not included above (i.e. • A gathering of family/friends or company/ volleyball nets, inflatables/bounce house, additional organization tables or canopies) • A single reserved picnic facility without exceeding • you’d like to drive a vehicle on the sidewalk to pick up or the stated site capacity drop off items for your event • When event attendance is free.