Bombs Educate Vigorously

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iraq's WMD Capability

BRITISH AMERICAN SECURITY INFORMATION COUNCIL BASIC SPECIAL REPORT Unravelling the Known Unknowns: Why no Weapons of Mass Destruction have been found in Iraq By David Isenberg and Ian Davis BASIC Special Report 2004.1 January 2004 1 The British American Security Information Council The British American Security Information Council (BASIC) is an independent research organization that analyzes international security issues. BASIC works to promote awareness of security issues among the public, policy makers and the media in order to foster informed debate on both sides of the Atlantic. BASIC in the U.K. is a registered charity no. 1001081 BASIC in the U.S. is a non-profit organization constituted under Section 501(c)(3) of the U.S. Internal Revenue Service Code David Isenberg, Senior Analyst David Isenberg joined BASIC's Washington office in November 2002. He has a wide background in arms control and national security issues, and brings close to 20 years of experience in this field, including three years as a member of DynMeridian's Arms Control & Threat Reduction Division, and nine years as Senior Analyst at the Center for Defense Information. Ian Davis, Director Dr. Ian Davis is Executive Director of BASIC and has a rich background in government, academia, and the non-governmental organization (NGO) sector. He received both his Ph.D. and B.A. in Peace Studies from the University of Bradford. He was formerly Program Manager at Saferworld before being appointed as the new Executive Director of BASIC in October 2001. He has published widely on British defense and foreign policy, European security, the international arms trade, arms export controls, small arms and light weapons and defense diversification. -

Cli-Fi: a Companion

Stef Craps Jeff Nichols’s Take Shelter (2011) Cli-Fi Psychic Released in 2011, Take Shelter is an American feature film written and directed by Jeff Nichols and starring Michael Shannon and Jessica Chastain.1 Set in LaGrange, Ohio, it tells the story of a family man and construction worker, called Curtis LaForche (Shannon), who is plagued by a series of apocalyptic nightmares and visions. He starts to believe that he is developing paranoid schizophrenia, the illness with which his now-institutionalized mother was diagnosed when she was a similar age and which he has feared inheriting his whole life. At the same time, he becomes increasingly obsessed with the need to shelter his family − his wife Samantha (Chastain) and their hearing-impaired young daughter Hannah − from the coming storm that he cannot help thinking his terrifying dreams and hallucinations signal. Foremost among the protective measures he takes to keep his family safe is the renovation and expansion of the tornado shelter in his backyard, which he can ill afford and which causes him to lose his job and his health insurance, as a result of which Hannah cannot have the cochlear implant surgery she was scheduled to undergo. The ques- tion of whether Curtis is a prophet or mentally disturbed drives the film and remains unresolved until the epilogue, when his premonitions turn out to be true as an actual end-of-the-world storm is about to hit. Take Shelter captures many of the anxieties of living in the post-9/11, post-Katrina and post-financial crisis USA, thanks to the ‘flexible metaphor’ of Curtis’s apocalyptic visions.2 Increasing in violence and intensity as the film progresses, they take the form of thunderstorms, twisters, flash floods, 1 Take Shelter, dir. -

Bendheim Senior Thesis Department of History, Columbia University

INCENDIARY WARS: The Transformation of United States Air Force Bombing Policy in the WWII Pacific Theater Gilad Bendheim Senior Thesis Department of History, Columbia University Faculty Advisor: Professor Mark Mazower Second Reader: Professor Alan Brinkley INCENDIARY WARS 1 Note to the Reader: For the purposes of this essay, I have tried to adhere to a few conventions to make the reading easier. When referring specifically to a country’s aerial military organization, I capitalize the name Air Force. Otherwise, when simply discussing the concept in the abstract, I write it as the lower case air force. In accordance with military standards, I also capitalize the entire name of all code names for operations (OPERATION MATTERHORN or MATTERHORN). Air Force’s names are written out (Twentieth Air Force), the bomber commands are written in Roman numerals (XX Bomber Command, or simply XX), while combat groups are given Arabic numerals (305th Bomber Group). As the story shifts to the Mariana Islands, Twentieth Air Force and XXI Bomber Command are used interchangeably. Throughout, the acronyms USAAF and AAF are used to refer to the United States Army Air Force, while the abbreviation of Air Force as “AF” is used only in relation to a numbered Air Force (e.g. Eighth AF). Table of Contents: Introduction 3 Part I: The (Practical) Prophets 15 Part II: Early Operations Against Japan 43 Part III: The Road to MEETINGHOUSE 70 Appendix 107 Bibliography 108 INCENDIARY WARS 2 Introduction Curtis LeMay sat awake with his trademark cigar hanging loosely from his pursed ever-scowling lips (a symptom of his Bell’s Palsy, not his demeanor), with two things on his mind. -

Weighing Evidence in an Information War

Weighing evidence in an information war Paul McKeigue Usher Institute of Population Health Sciences and Informatics 23 January 2019 Fake news and disinformation Government response to the House of Commons Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee (2018): • ‘fake news’ is a poorly-defined and misleading term that conflates a variety of false information, from genuine error through to foreign interference in democratic processes • the Government has sought to move away from ‘fake news’ and instead has sought to address ‘disinformation’ and wider online manipulation. • we have defined disinformation as the deliberate creation and sharing of false and/or manipulated information that is intended to deceive and mislead audiences, either for the purposes of causing harm, or for political, personal or financial gain. • we will consider options to improve critical thinking skills and resilience to disinformation in the context of political engagement. Disinformation, conspiracy theory or truth? – some disputed explanations Official Year Event explanation Alternative explanation 1981 Yellow rain in Laos Communist Mass defecation flights of and Cambodia mycotoxin Asian honeybees warfare 2001 WTC collapse Hijacked aircraft Planned demolition 2006 Litvinenko poisoning Russian assassins Accidental mishandling of polonium 2013- Alleged chemical Regime chemical Managed massacre of 18 attacks in Syria warfare captives 2016 Brexit referendum Revolt against Manipulation of voters by result migration policy informatics companies 2017 Noise-induced illness Communist -

Explosive Weapon Effectsweapon Overview Effects

CHARACTERISATION OF EXPLOSIVE WEAPONS EXPLOSIVEEXPLOSIVE WEAPON EFFECTSWEAPON OVERVIEW EFFECTS FINAL REPORT ABOUT THE GICHD AND THE PROJECT The Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) is an expert organisation working to reduce the impact of mines, cluster munitions and other explosive hazards, in close partnership with states, the UN and other human security actors. Based at the Maison de la paix in Geneva, the GICHD employs around 55 staff from over 15 countries with unique expertise and knowledge. Our work is made possible by core contributions, project funding and in-kind support from more than 20 governments and organisations. Motivated by its strategic goal to improve human security and equipped with subject expertise in explosive hazards, the GICHD launched a research project to characterise explosive weapons. The GICHD perceives the debate on explosive weapons in populated areas (EWIPA) as an important humanitarian issue. The aim of this research into explosive weapons characteristics and their immediate, destructive effects on humans and structures, is to help inform the ongoing discussions on EWIPA, intended to reduce harm to civilians. The intention of the research is not to discuss the moral, political or legal implications of using explosive weapon systems in populated areas, but to examine their characteristics, effects and use from a technical perspective. The research project started in January 2015 and was guided and advised by a group of 18 international experts dealing with weapons-related research and practitioners who address the implications of explosive weapons in the humanitarian, policy, advocacy and legal fields. This report and its annexes integrate the research efforts of the characterisation of explosive weapons (CEW) project in 2015-2016 and make reference to key information sources in this domain. -

Former Warsaw Pact Ammunition Handbook, Vol 3

NATO Explosive Ordnance Disposal Centre of Excellence FORMER WARSAW PACT AMMUNITION HANDBOOK VOLUME 3 Air Forces Ammunition Aerial projectiles, bombs, rockets and missiles TRENČÍN 2019 Slovak Republic For Official Use Only Explosive Ordnance Disposal Centre of Excellence FORMER WARSAW PACT AMMUNITION HANDBOOK VOLUME 3 Air Forces Ammunition Aerial projectiles, bombs, rockets and missiles For Official Use Only Explosive Ordnance Disposal Centre of Excellence The NATO Explosive Ordnance Centre of Excellence (NATO EOD COE) supports the efforts of the Alliance in the areas of training and education, information sharing, doctrine development and concepts validation. Published by NATO EOD Centre of Excellence Ivana Olbrachta 5, 911 01,Trenčín, Slovak Republic Tel. + 421 960 333 502, Fax + 421 960 333 504 www.eodcoe.org Former Warsaw Pact Ammunition Handbook VOL 3 – Edition II. ISBN 978-80-89261-81-9 © EOD Centre of Excellence. All rights reserved 2019 No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without the written permission of the publisher, except in the case brief quotations embodied in articles and reviews. For Official Use Only Explosive Ordnance Disposal Centre of Excellence Foreword Even though in areas of current NATO operations the insurgency is vastly using the Home Made Explosive as the main charge for emplaced IEDs, our EOD troops have to cope with the use of the conventional munition in any form and size all around the world. To assist in saving EOD Operators’ lives and to improve their effectiveness at munition disposal, it is essential to possess the adequate level of experience and knowledge about the respective type of munition. -

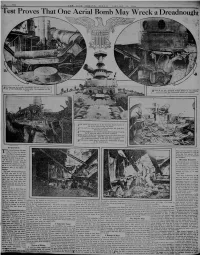

Test Proves That One Aerial Bomb Maywreck a Dreadnought

" " " * v " **. ^»*i>l-' J U ill/ A 1 LIB, , il.iiM Altl ¿ ¿ , 1 íJ ¿ 1 I I_.' ___ _ Test Proves That One Aerial Bomb May Wreck a Dreadnought A LL that was left of the wheelhouse and the forward fun- **¦ nel of the battleship Indiana after the explosion of the bomb '"TI/RECK of the forward 8-inch turret of the Indiana, j against tvhich the 900-pound bomb ivas exploded F "" smmsMsmsssssssssssimsmssMsssssssMswsMSSMsWSMsss^ rVHE bomb was the ¦*¦ placed aft of forward 8-inch turret at the point indicated by the arrmo i ; A T the left is a view of the vessel the amidships> first deck { .,.** being blown away \ A T THE right is a view of the second deck looking forward, ^ the X showing where the bomb exploded j ITHE picture at the lower left hand show's the third deck and -* the ammunition hoist. Had the ship been in commission the magazine probably ivould have been exploded j AT the lower hand is shown the **¦ right destruction wrought I on the fourth deck I _..-..__ ____-.... < By Quarterdeck THE seven pictures on this page there, and the campaign could not suffice to show the destruc¬ have been undertaken at all if th« tive effect of a bomb, not only Turks had been supplied with ar- on the upper works of a air force, not to speak of submarine* battleship, and bot upon the lower decks as well. torpedoes. In this case the target was the Discussion Demanded old battleship Indiana, formerly This article is not sensational It commanded by Captain H. -

Soviet Active Measures an Update Jul 1982.P65

Special Report No. 101 Soviet Active Measures: An Update July 1982 United States Department of State Bureau of Public Affairs Washington, D.C. This report describes Soviet active Forgeries After an initial mailing to Spanish measures which have come to light since journalists failed to obtain publication, the the publication of Special Report No. 88, Forgeries are a frequently used active forgery was circulated on November 11 to Soviet Active Measures: Forgery, measures technique. Several have come to all delegations (except the U.S and Spanish) Disinformation, Political Operations, in light in recent months. Their appearance has to the Conference of Security and Coopera- October 1981. been timed to influence Western opinion on tion in Europe (CSCE), then meeting in current sensitive issues. As far as we are Madrid. This time several Madrid newspa- The Soviet Union uses the term active aware, only one of these recent forgeries pers ran stories that exposed the letter as a measures (aktivnyye meropriyatiya) to achieved uncritical publication. fabrication probably of Soviet origin. cover a broad range of activities designed to Forgeries are usually sent through the promote Soviet foreign policy goals, mail to journalists, officials, or other persons The Clark-Stearns Letter. In January including undercutting opponents of the who might make them available to the 1982, a forged letter and an accompanying U.S.S.R. Active measures include media. Forgeries normally do not carry a research analysis dated September 23, 1981, disinformation, manipulating the media in return address, nor is the sender identified in from Judge William Clark, then Deputy foreign countries, the use of Communist a way that can be checked. -

Basic Special Report

BRITISH AMERICAN SECURITY INFORMATION COUNCIL BASIC SPECIAL REPORT Unravelling the Known Unknowns: Why no Weapons of Mass Destruction have been found in Iraq By David Isenberg and Ian Davis BASIC Special Report 2004.1 January 2004 1 The British American Security Information Council The British American Security Information Council (BASIC) is an independent research organization that analyzes international security issues. BASIC works to promote awareness of security issues among the public, policy makers and the media in order to foster informed debate on both sides of the Atlantic. BASIC in the U.K. is a registered charity no. 1001081 BASIC in the U.S. is a non-profit organization constituted under Section 501(c)(3) of the U.S. Internal Revenue Service Code David Isenberg, Senior Analyst David Isenberg joined BASIC's Washington office in November 2002. He has a wide background in arms control and national security issues, and brings close to 20 years of experience in this field, including three years as a member of DynMeridian's Arms Control & Threat Reduction Division, and nine years as Senior Analyst at the Center for Defense Information. Ian Davis, Director Dr. Ian Davis is Executive Director of BASIC and has a rich background in government, academia, and the non-governmental organization (NGO) sector. He received both his Ph.D. and B.A. in Peace Studies from the University of Bradford. He was formerly Program Manager at Saferworld before being appointed as the new Executive Director of BASIC in October 2001. He has published widely on British defense and foreign policy, European security, the international arms trade, arms export controls, small arms and light weapons and defense diversification. -

Concept Plan for the Destruction of Eight Old Chemical Weapons

OPCW Executive Council Eighty-Fifth Session EC-85/NAT.2 11 – 14 July 2017 16 June 2017 ENGLISH Original: SPANISH PANAMA CONCEPT PLAN FOR THE DESTRUCTION OF EIGHT OLD CHEMICAL WEAPONS Background 1. The Republic of Panama has declared eight (8) old chemical weapons to be destroyed. The weapons are located on San José Island, off the Southern coast of Panama’s mainland. The eight chemical munitions are World War II-era and comprised of: six (6) M79, 1,000 lb. aerial bombs believed to contain the Schedule 3 toxic chemical phosgene (CG), also known as carbonyl dichloride; one (1) M78, 500 lb. aerial bomb believed to contain the Schedule 3 toxic chemical cyanogen chloride (CK); and one (1) M1A1 Cylinder, which has been confirmed empty and rusted through and which the Republic of Panama and the Technical Secretariat (hereinafter “the Secretariat”) of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) considered destroyed. All eight of these munitions were identified in the 2002 OPCW Technical Secretariat Final Inspection Report. 2. The Republic of Panama has determined that the seven bombs are unsafe to move because of their explosive configuration, age, and austere location. These characteristics were noted in the 2002 OPCW Technical Secretariat Final Inspection Report. Relocation would pose an undue risk to workers attempting to move them and to the environment. As such, the Republic of Panama plans to destroy the munitions in place. 3. The OPCW Secretariat agrees with the Republic of Panama’s assessment that there is no viable transportation option to remove the items for destruction elsewhere in the Republic of Panama or outside of the Republic of Panama. -

Security and Society in the Information Age Vol. 3

SECURITY Katarzyna MANISZEWSKA, Paulina PIASECKA Editors AND SOCIETY IIt is our pleasure to present a third scholarly volume bringing together a unique series of research papers by talented students – participants in the Security and Society in the Information Age program held at Collegium Civitas University in AGE IN THE INFORMATION Warsaw, Poland. In 2020, due to the pandemic, the program was held for first time online and included a component on the security-related implications of Covid-19. The students took part in a fully-fledged online course followed by an online research internship at the Terrorism Research Center. This book presents the results of their SECUR TY work – research papers devoted to contemporary security threats. The contributors not only analyzed the issues but also looked for solutions and these papers include recommendations for policy makers. We hope you will find this book interesting and valuable and we cordially invite you to learn more about the Security and Society in the Information Age program at: www. AND securityandsociety.org Volume 3 SOCIETY IN THE INFORMATION AGE Volume 3 ISBN 978-83-66386-15-0 9 788366 386150 Volume 3 COLLEGIUM CIVITAS „Security and Society in the Information Age. Volume 3” publication is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License under the following terms – you must keep this information and credit Collegium Civitas as the holder of the copyrights to this publication. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ Reviews: Daniel Boćkowski, PhD, University of Bialystok Marek Jeznach, PhD, an independent security researcher Editors: Katarzyna Maniszewska, PhD ( https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8021-8135) and Paulina Piasecka, PhD ( https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3133-8154) Proofreader: Vanessa Tinker, PhD e-ISBN: 978-83-66386-15-0 ISBN-print: 978-83-66386-16-7 DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.13614143 Publisher: Collegium Civitas Press Palace of Culture and Science, XI floor 00-901 Warsaw, 1 Defilad Square tel. -

Conventional Weapons

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 45 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. First published in the UK in 2009 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Printed by Windrush Group Windrush House Avenue Two Station Lane Witney OX28 4XW 3 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-Marshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman Group Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary Group Captain K J Dearman FRAeS Membership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol AMRAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA Members Air Commodore G R Pitchfork MBE BA FRAes *J S Cox Esq BA MA *Dr M A Fopp MA FMA FIMgt *Group Captain A J Byford MA MA RAF *Wing Commander P K Kendall BSc ARCS MA RAF Wing Commander C Cummings Editor & Publications Wing Commander C G Jefford MBE BA Manager *Ex Officio 4 CONTENTS RFC BOMBS & BOMBING 1912-1918 by AVM Peter Dye 8 THE DEVELOPMENT OF RAF BOMBS, 1919-1939 by 15 Stuart Hadaway RAF BOMBS AND BOMBING 1939-1945 by Nina Burls 25 THE DEVELOPMENT OF RAF GUNS AND 37 AMMUNITION FROM WORLD WAR 1 TO THE