The Hummingbird Community and Their Floral Resources in an Urban Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Birds of Reserva Ecológica Guapiaçu (REGUA)

Cotinga 33 The birds of Reserva Ecológica Guapiaçu (REGUA), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Leonardo Pimentel and Fábio Olmos Received 30 September 2009; final revision accepted 15 December 2010 Cotinga 33 (2011): OL 8–24 published online 16 March 2011 É apresentada uma lista da avifauna da Reserva Ecológica de Guapiaçu (REGUA), uma reserva privada de 6.500 ha localizada no município de Cachoeiras de Macacu, vizinha ao Parque Estadual dos Três Picos, Estação Ecológica do Paraíso e Parque Nacional da Serra dos Órgãos, parte de um dos maiores conjuntos protegidos do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Foram registradas um total de 450 espécies de aves, das quais 63 consideradas de interesse para conservação, como Leucopternis lacernulatus, Harpyhaliaetus coronatus, Triclaria malachitacea, Myrmotherula minor, Dacnis nigripes, Sporophila frontalis e S. falcirostris. A reserva também está desenvolvendo um projeto de reintrodução dos localmente extintos Crax blumembachii e Aburria jacutinga, e de reforço das populações locais de Tinamus solitarius. The Atlantic Forest of eastern Brazil and Some information has been published on neighbouring Argentina and Paraguay is among the birds of lower (90–500 m) elevations in the the most imperilled biomes in the world. At region10,13, but few areas have been subject to least 188 bird species are endemic to it, and 70 long-term surveys. Here we present the cumulative globally threatened birds occur there, most of them list of a privately protected area, Reserva Ecológica endemics4,8. The Atlantic Forest is not homogeneous Guapiaçu (REGUA), which includes both low-lying and both latitudinal and longitudinal gradients parts of the Serra dos Órgãos massif and nearby account for diverse associations of discrete habitats higher ground, now mostly incorporated within and associated bird communities. -

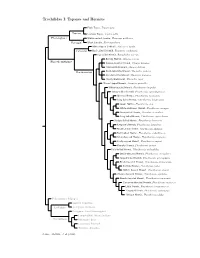

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Flowers Visited by Hummingbirds in an Urban Cerrado Fragment, Mato Grosso Do Sul, Brazil

Biota Neotrop., vol. 13, no. 4 Flowers visited by hummingbirds in an urban Cerrado fragment, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil Waldemar Guimarães Barbosa-Filho1,2 & Andréa Cardoso de Araujo1 1Laboratório de Ecologia, Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul – UFMS, CP 549, CEP 79070-900, Campo Grande, MS, Brasil. http://www-nt.ufms.br/ 2Corresponding author: Waldemar Guimarães Barbosa-Filho, e-mail: [email protected] BARBOSA-FILHO, W.G. & ARAUJO, A.C. Flowers visited by hummingbirds in an urban Cerrado fragment, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Biota Neotrop. 13(4): http://www.biotaneotropica.org.br/v13n4/en/ abstract?article+bn00213042013 Abstract: Hummingbirds are the main vertebrate pollinators in the Neotropics, but little is known about the interactions between hummingbirds and flowers in areas of Cerrado. This paper aims to describe the interactions between flowering plants (ornithophilous and non-ornithophilous species) and hummingbirds in an urban Cerrado remnant. For this purpose, we investigated which plant species are visited by hummingbirds, which hummingbird species occur in the area, their visiting frequency and behavior, their role as legitimate or illegitimate visitors, as well as the number of agonistic interactions among these visitors. Sampling was conducted throughout 18 months along a track located in an urban fragment of Cerrado vegetation in Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil. We found 15 species of plants visited by seven species of hummingbirds. The main habit for ornithophilous species was herbaceous, with the predominance of Bromeliaceae; among non-ornithophilous most species were trees from the families Vochysiaceae and Malvaceae. -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit Vergleichende phytochemische Untersuchungen an ausgewählten Arten der Gattung Psychotria (Rubiaceae) verfasst von Theresa Gruber angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Naturwissenschaften (Mag.rer.nat.) Wien, 2015 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 190 406 445 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Lehramtsstudium UF Mathematik UF Biologie und Umweltkunde Betreut von: ao. Univ.- Prof. Dr. Karin Vetschera Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung ..................................................................................................................... 1 2 Systematik, Taxonomie und Morphologie der Gattung Psychotria L. ............................ 2 2.1. Die Ordnung Gentianales ..................................................................................... 3 2.2. Die Familie der Rubiaceae ................................................................................... 3 2.3. Einordnung der untersuchten Artengruppe innerhalb der Rubiaceae .................... 4 3 Phytochemische Aspekte ............................................................................................. 6 3.1. Isoprenoide und deren Biosynthese...................................................................... 6 3.1.1. Zwei alternative Biosynthesewege führen zur Bildung von IPP und DMAPP .. 7 3.2. Iridoide ................................................................................................................. 9 3.2.1. Bioaktive Wirkung von Iridoiden und deren Rolle in der Pflanze .................. 12 3.2.2. -

New Data Concerning the Distribution, Behaviour, Ecology and Taxonomic Relationships of Minas Gerais Tyrannulet Phylloscartes Roquettei

Bird Conservation International (2002) 12:241–253. BirdLife International 2002 DOI: 10.1017/S0959270902002150 Printed in the United Kingdom New data concerning the distribution, behaviour, ecology and taxonomic relationships of Minas Gerais Tyrannulet Phylloscartes roquettei MARCOS A. RAPOSO, JUAN MAZAR BARNETT, GUY M. KIRWAN and RICARDO PARRINI Summary We report new observations of the globally threatened Minas Gerais Tyrannulet Phylloscartes roquettei from two areas in the Sa˜o Francisco Valley, Minas Gerais, Brazil, between July 1993 and February 2002. Four pairs, one fledged young and two lone individuals were observed in the course of our fieldwork. It was previously known only from a female taken in the mid-1920s and sight records and tape-recordings in 1977.Our records extend the species’ known range 250 km south and west of the type-locality region. Details of the first-known male specimen are presented, along with novel data concerning its vocalizations and behaviour. We draw attention to the possible relationship of the species to a group of four other Phylloscartes tyrannulets with similarly patterned faces and overall plumage, which exhibit a similar circum-Amazonian distribution pattern to three Phyllomyias tyrannulets. We also take the opportunity to draw more attention to the imperilled conservation status of the dry forests upon which P. roquettei and a host of other threatened and Near-threatened avian taxa depend. Resumo Sa˜o apresentadas novas observac¸o˜es sobre a espe´cie pouco conhecida e ameac¸ada Phylloscartes roquettei, endeˆmica do vale do rio Sa˜o Francisco, Minas Gerais, Brasil, realizadas entre os anos de 1993 e 2002. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

ON (19) 599-606.Pdf

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 19: 599–606, 2008 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society BODY MASSES OF BIRDS FROM ATLANTIC FOREST REGION, SOUTHEASTERN BRAZIL Iubatã Paula de Faria1 & William Sousa de Paula PPG-Ecologia, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, DF, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] Massa corpórea de aves da região de Floresta Atlântica, sudeste do Brasil. Key words: Neotropical birds, weight, body mass, tropical rainforest, Brazil. The Brazilian Atlantic forest is one of the In this paper, we present the values of biodiversity hotspots in the world (Myers body masses of birds captured or collected 1988, Myers et al. 2000) with high endemism using mist-nets in 17 localities in the Atlantic of bird species (Cracraft 1985, Myers et al. forest of southeastern Brazil (Table 1), 2000). Nevertheless, there is little information between 2004 and 2007. Data for sites 1, 2, 3, on the avian body masses (weight) for this and 5 were collected in January, April, August, region (Oniki 1981, Dunning 1992, Belton and December 2004; in March and April 2006 1994, Reinert et al. 1996, Sick 1997, Oniki & for sites 4, 6, 7, and 8. Others sites were col- Willis 2001, Bugoni et al. 2002) and for other lected in September 2007. The Atlantic forest Neotropical ecosystems (Fry 1970, Oniki region is composed by two major vegetation 1980, 1990; Dick et al. 1984, Salvador 1988, types: Atlantic rain forest (low to medium ele- 1990; Peris 1990, Dunning 1992, Cavalcanti & vations, = 1000 m); and Atlantic semi-decidu- Marini 1993, Marini et al. 1997, Verea et al. ous forest (usually > 600 m) (Morellato & 1999, Oniki & Willis 1999). -

Project Scientific Progress Report Study Site

Project Ecology of plant-hummingbird interactions along an elevational gradient Scientific Progress Report Project leader: Catherine Graham, Swiss Federal Research Institute Principal investigator: María Alejandra Maglianesi, Universidad Estatal a Distancia Coordinator: Emanuel Brenes Rodríguez, Universidad Estatal a Distancia Study site Las Nubes Biological Reserve York University San José, Costa Rica January, 2020 1 INTRODUCTION A primary aim of community ecology is to identify the processes that govern species assemblages across environmental gradients (McGill et al. 2006), allowing us to understand why biodiversity is non-randomly distributed on Earth. Mutualistic interactions such as those between plants and their animal pollinators are the major biodiversity component from which the integrity of ecosystems depends (Valiente-Banuet et al. 2015). The interdependence of plant and pollinators can be assessed using a network approach, which is a powerful tool to analyze the complexity of ecological systems (Ings et al. 2009), especially in highly diversified tropical regions. Mountain regions provide pronounced environmental gradients across relatively small spatial scales and have proved to be a suitable model system to investigate patterns and determinants of species diversity and community structure (Körner 2000, Sanders and Rahbek 2012). Although some studies have investigated the variation in plant–pollinator interaction networks across elevational gradients (Ramos-Jiliberto et al. 2010, Benadi et al. 2013), such studies are still scarce, particularly in the tropics. In the Neotropics, hummingbirds (Trochilidae) are considered to be effective pollinators (Castellanos et al. 2003). They have been classified into two distinct groups: hermits and non-hermits, which differ mainly in their elevational distribution and their level of specialization on floral resources, i.e., the proportion of floral resources available in the community that is used by species (Stiles 1978). -

Synopsis and Typification of Mexican and Central American

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien Jahr/Year: 2018 Band/Volume: 120B Autor(en)/Author(s): Berger Andreas Artikel/Article: Synopsis and typification of Mexican and Central American Palicourea (Rubiaceae: Palicoureeae), part I: The entomophilous species 59-140 ©Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, download unter www.zobodat.at Ann. Naturhist. Mus. Wien, B 120 59–140 Wien, Jänner 2018 Synopsis and typification of Mexican and Central American Palicourea (Rubiaceae: Palicoureeae), part I: The entomophilous species A. Berger* Abstract The prominent but complex genus Psychotria (Rubiaceae: Psychotrieae) is one of the largest genera of flow- ering plants and its generic circumscription has been controversial for a long time. Recent DNA-phyloge- netic studies in combination with a re-evaluation of morphological characters have led to a disintegration process that peaked in the segregation of hundreds of species into various genera within the new sister tribe Palicoureeae. These studies have also shown that species of Psychotria subg. Heteropsychotria are nested within Palicourea, which was traditionally separated by showing an ornithophilous (vs. entomophilous) pol- lination syndrome. In order to render the genera Palicourea and Psychotria monophyletic groups, all species of subg. Heteropsychotria have to be transferred to Palicourea and various authors and publications have provided some of the necessary combinations. In the course of ongoing research on biotic interactions and chemodiversity of the latter genus, the need for a comprehensive and modern compilation of species of Pali courea in its new circumscription became apparent. As first step towards such a synopsis, the entomophilous Mexican and Central American species (the traditional concept of Psychotria subg. -

Chec List What Survived from the PLANAFLORO Project

Check List 10(1): 33–45, 2014 © 2014 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution What survived from the PLANAFLORO Project: PECIES S Angiosperms of Rondônia State, Brazil OF 1* 2 ISTS L Samuel1 UniCarleialversity of Konstanz, and Narcísio Department C.of Biology, Bigio M842, PLZ 78457, Konstanz, Germany. [email protected] 2 Universidade Federal de Rondônia, Campus José Ribeiro Filho, BR 364, Km 9.5, CEP 76801-059. Porto Velho, RO, Brasil. * Corresponding author. E-mail: Abstract: The Rondônia Natural Resources Management Project (PLANAFLORO) was a strategic program developed in partnership between the Brazilian Government and The World Bank in 1992, with the purpose of stimulating the sustainable development and protection of the Amazon in the state of Rondônia. More than a decade after the PLANAFORO program concluded, the aim of the present work is to recover and share the information from the long-abandoned plant collections made during the project’s ecological-economic zoning phase. Most of the material analyzed was sterile, but the fertile voucher specimens recovered are listed here. The material examined represents 378 species in 234 genera and 76 families of angiosperms. Some 8 genera, 68 species, 3 subspecies and 1 variety are new records for Rondônia State. It is our intention that this information will stimulate future studies and contribute to a better understanding and more effective conservation of the plant diversity in the southwestern Amazon of Brazil. Introduction The PLANAFLORO Project funded botanical expeditions In early 1990, Brazilian Amazon was facing remarkably in different areas of the state to inventory arboreal plants high rates of forest conversion (Laurance et al. -

Juan Cristóbal Gundlach's Collections of Puerto Rican Birds with Special

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Zoosystematics and Evolution Jahr/Year: 2015 Band/Volume: 91 Autor(en)/Author(s): Frahnert Sylke, Roman Rafela Aguilera, Eckhoff Pascal, Wiley James W. Artikel/Article: Juan Cristóbal Gundlach’s collections of Puerto Rican birds with special regard to types 177-189 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence (CC-BY); original download https://pensoft.net/journals Zoosyst. Evol. 91 (2) 2015, 177–189 | DOI 10.3897/zse.91.5550 museum für naturkunde Juan Cristóbal Gundlach’s collections of Puerto Rican birds with special regard to types Sylke Frahnert1, Rafaela Aguilera Román2, Pascal Eckhoff1, James W. Wiley3 1 Museum für Naturkunde, Leibniz-Institut für Evolutions- und Biodiversitätsforschung, Invalidenstraße 43, D-10115 Berlin, Germany 2 Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática, La Habana, Cuba 3 PO Box 64, Marion Station, Maryland 21838-0064, USA http://zoobank.org/B4932E4E-5C52-427B-977F-83C42994BEB3 Corresponding author: Sylke Frahnert ([email protected]) Abstract Received 1 July 2015 The German naturalist Juan Cristóbal Gundlach (1810–1896) conducted, while a resident Accepted 3 August 2015 of Cuba, two expeditions to Puerto Rico in 1873 and 1875–6, where he explored the Published 3 September 2015 southwestern, western, and northeastern regions of this island. Gundlach made repre sentative collections of the island’s fauna, which formed the nucleus of the first natural Academic editor: history museums in Puerto Rico. When the natural history museums closed, only a few Peter Bartsch specimens were passed to other institutions, including foreign museums. None of Gund lach’s and few of his contemporaries’ specimens have survived in Puerto Rico. -

Georgetown Botanical Gardens Bird Checklist

Georgetown Botanical Gardens Bird Checklist October 2008 Georgetown Botanical Gardens: Bird Checklist ________________________________________________________ A matter of minutes from the centre of Georgetown, the Botanical Gardens are readily accessible from all main tourist hotels in the city and offer the visiting birder an opportunity to see a wide range of species: English Name Scientific name Ducks & Geese Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis Cormorants Neotropic Cormorant Phalacrocorax brasilianus Herons Boat-billed Heron Cochlearius cochlearius Black-crowned Night-Heron Nycticorax nycticorax Yellow-crowned Night-Heron Nyctanassa violacea Striated Heron Butorides striatus Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis Great Egret Ardea alba Tricolored Heron Egretta tricolor Snowy Egret Egretta thula Little Blue Heron Egretta caerulea Vultures Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura Lesser Yellow-headed Vulture Cathartes burrovianus Greater Yellow-headed Vulture Cathartes melambrotus Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Hawks & Eagles Osprey Pandion haliaetus Swallow-tailed Kite Elanoides forficatus Pearl Kite Gamsonyx swainsonii Snail Kite Rostrhamus sociabilis Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Crane Hawk Geranospiza caerulescens Gray Hawk Asturina nitida Savanna Hawk Buteogallus meridionalis Black-collared Hawk Busarellus nigricollis Roadside Hawk Buteo magnirostris Short-tailed Hawk Buteo brachyurus Page 1 Georgetown Botanical Gardens: Bird Checklist ________________________________________________________ Falcons & Caracaras Northern (Crested)