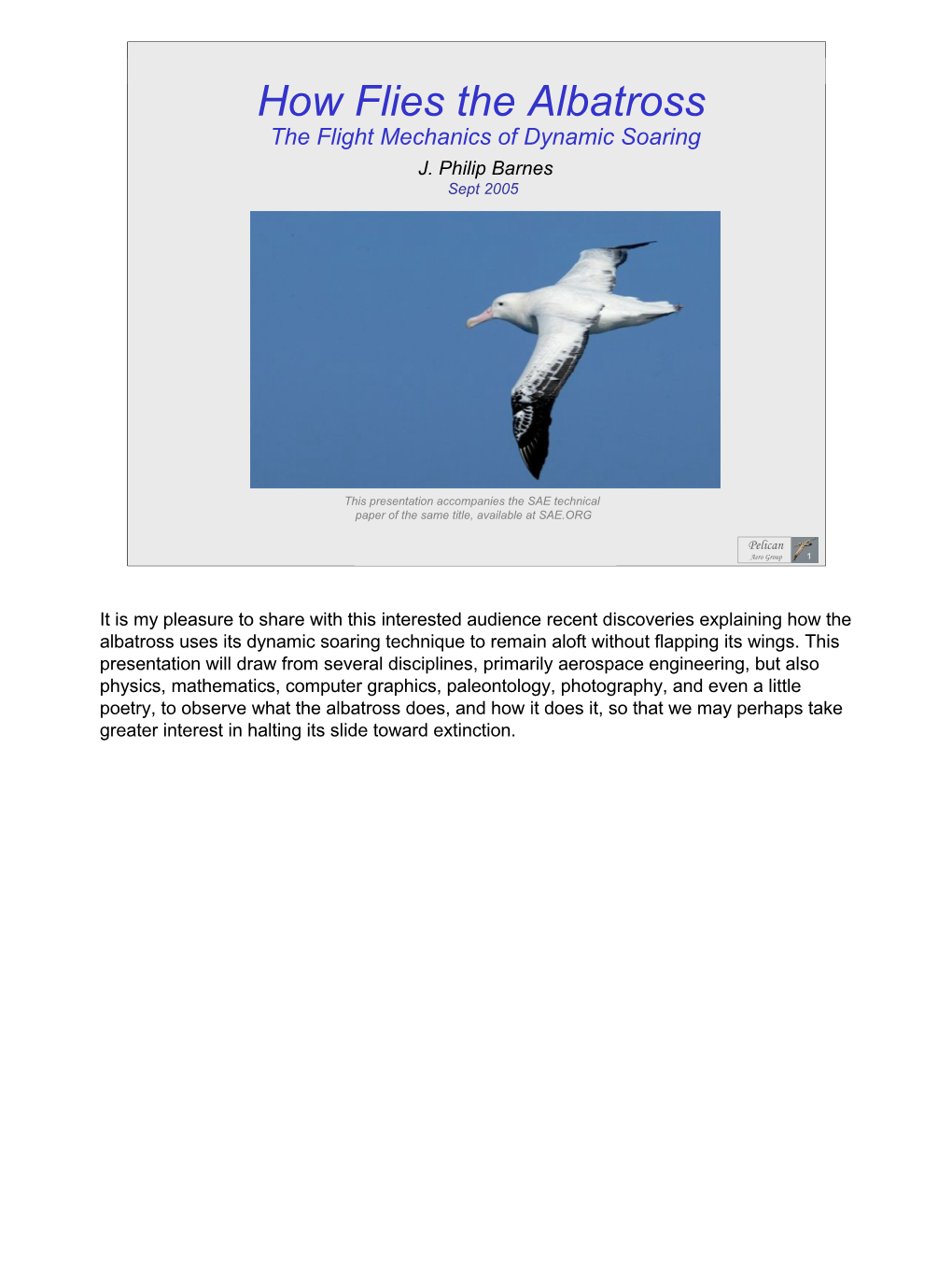

How Flies the Albatross the Flight Mechanics of Dynamic Soaring J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F:\Boletín SVE\No.37\SOURCE\37

Bol. Soc. Venezolana Espeleol. 37: 27-30, 2003 BIOESPELEOLOGÍA PRIMER REGISTRO DE LA FAMILIA PELAGORNITHIDAE (AVES: PELECANIFORMES) PARA VENEZUELA Ascanio D. RINCÓN R.1 y Marcelo STUCCHI 2 han identificado nueve géneros, la mayor parte procedentes de 1. Laboratorio de Biología de Organismos, Centro de Ecología, América del Norte y Europa: Odontopteryx, Neodontornis, Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas (IVIC) Macrodontornis, Dasornis, Argillornis, Gigantornis, Carretera Panamericana, Km 11, Aptdo. 21827, Cod. Postal Osteodontornis, Pseudodontornis y Pelagornis (Harrison & 1020-A Caracas – VENEZUELA & Sociedad Venezolana de Walker, 1976). Espeleología. Apartado 47334. Caracas 1041A. VENEZUELA. En América del Sur, los Pelagornithidae han sido registrados Correo electrónico: [email protected] hasta el momento en sólo dos localidades: la Formación Bahía 2. Asociación Ucumari, Jr. Los Agrólogos 220. Lima 12, Perú. Inglesa (norte de Chile) de edad Mioceno Tardío y la Formación Correo electrónico: [email protected] Pisco (centro-sur del Perú) de edad Mioceno Medio - Plioceno Temprano. En la primera de ellas, se ha reconocido Recibido en octubre de 2004 Pseudodontornis cf. longirostris y en la segunda Pelagornis cf. miocaenus (Chávez & Stucchi, 2002). Para la Antártida, Tonni (1980) y Tonni & Tambussi (1985) RESUMEN han referido material sólo a nivel familiar procedente de la For- Se registra la presencia de la familia Pelagornithidae (Aves: mación La Meseta (Isla Vicecomodoro Marambio) de edad Eo- Pelecaniformes) en Venezuela. El ejemplar proviene de la Cueva del Zum- Oligoceno. bador, la cual se desarrolla en calizas del Mioceno Medio de la Forma- El material estudiado en la presente nota, proviene de la Cueva ción Capadare afloradas en el Cerro Misión al oriente del estado Falcón, del Zumbador la cual se desarrolla en las calizas de la Formación Venezuela. -

71St Annual Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Paris Las Vegas Las Vegas, Nevada, USA November 2 – 5, 2011 SESSION CONCURRENT SESSION CONCURRENT

ISSN 1937-2809 online Journal of Supplement to the November 2011 Vertebrate Paleontology Vertebrate Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Society of Vertebrate 71st Annual Meeting Paleontology Society of Vertebrate Las Vegas Paris Nevada, USA Las Vegas, November 2 – 5, 2011 Program and Abstracts Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 71st Annual Meeting Program and Abstracts COMMITTEE MEETING ROOM POSTER SESSION/ CONCURRENT CONCURRENT SESSION EXHIBITS SESSION COMMITTEE MEETING ROOMS AUCTION EVENT REGISTRATION, CONCURRENT MERCHANDISE SESSION LOUNGE, EDUCATION & OUTREACH SPEAKER READY COMMITTEE MEETING POSTER SESSION ROOM ROOM SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS SEVENTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING PARIS LAS VEGAS HOTEL LAS VEGAS, NV, USA NOVEMBER 2–5, 2011 HOST COMMITTEE Stephen Rowland, Co-Chair; Aubrey Bonde, Co-Chair; Joshua Bonde; David Elliott; Lee Hall; Jerry Harris; Andrew Milner; Eric Roberts EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Philip Currie, President; Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Past President; Catherine Forster, Vice President; Christopher Bell, Secretary; Ted Vlamis, Treasurer; Julia Clarke, Member at Large; Kristina Curry Rogers, Member at Large; Lars Werdelin, Member at Large SYMPOSIUM CONVENORS Roger B.J. Benson, Richard J. Butler, Nadia B. Fröbisch, Hans C.E. Larsson, Mark A. Loewen, Philip D. Mannion, Jim I. Mead, Eric M. Roberts, Scott D. Sampson, Eric D. Scott, Kathleen Springer PROGRAM COMMITTEE Jonathan Bloch, Co-Chair; Anjali Goswami, Co-Chair; Jason Anderson; Paul Barrett; Brian Beatty; Kerin Claeson; Kristina Curry Rogers; Ted Daeschler; David Evans; David Fox; Nadia B. Fröbisch; Christian Kammerer; Johannes Müller; Emily Rayfield; William Sanders; Bruce Shockey; Mary Silcox; Michelle Stocker; Rebecca Terry November 2011—PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 1 Members and Friends of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, The Host Committee cordially welcomes you to the 71st Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Las Vegas. -

Onetouch 4.0 Scanned Documents

/ Chapter 2 THE FOSSIL RECORD OF BIRDS Storrs L. Olson Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC. I. Introduction 80 II. Archaeopteryx 85 III. Early Cretaceous Birds 87 IV. Hesperornithiformes 89 V. Ichthyornithiformes 91 VI. Other Mesozojc Birds 92 VII. Paleognathous Birds 96 A. The Problem of the Origins of Paleognathous Birds 96 B. The Fossil Record of Paleognathous Birds 104 VIII. The "Basal" Land Bird Assemblage 107 A. Opisthocomidae 109 B. Musophagidae 109 C. Cuculidae HO D. Falconidae HI E. Sagittariidae 112 F. Accipitridae 112 G. Pandionidae 114 H. Galliformes 114 1. Family Incertae Sedis Turnicidae 119 J. Columbiformes 119 K. Psittaciforines 120 L. Family Incertae Sedis Zygodactylidae 121 IX. The "Higher" Land Bird Assemblage 122 A. Coliiformes 124 B. Coraciiformes (Including Trogonidae and Galbulae) 124 C. Strigiformes 129 D. Caprimulgiformes 132 E. Apodiformes 134 F. Family Incertae Sedis Trochilidae 135 G. Order Incertae Sedis Bucerotiformes (Including Upupae) 136 H. Piciformes 138 I. Passeriformes 139 X. The Water Bird Assemblage 141 A. Gruiformes 142 B. Family Incertae Sedis Ardeidae 165 79 Avian Biology, Vol. Vlll ISBN 0-12-249408-3 80 STORES L. OLSON C. Family Incertae Sedis Podicipedidae 168 D. Charadriiformes 169 E. Anseriformes 186 F. Ciconiiformes 188 G. Pelecaniformes 192 H. Procellariiformes 208 I. Gaviiformes 212 J. Sphenisciformes 217 XI. Conclusion 217 References 218 I. Introduction Avian paleontology has long been a poor stepsister to its mammalian counterpart, a fact that may be attributed in some measure to an insufRcien- cy of qualified workers and to the absence in birds of heterodont teeth, on which the greater proportion of the fossil record of mammals is founded. -

A Review of the Fossil Seabirds from the Tertiary of the North Pacific

Paleobiology,18(4), 1992, pp. 401-424 A review of the fossil seabirds fromthe Tertiaryof the North Pacific: plate tectonics,paleoceanography, and faunal change Kenneth I. Warheit Abstract.-Ecologists attempt to explain species diversitywithin Recent seabird communities in termsof Recent oceanographic and ecological phenomena. However, many of the principal ocean- ographic processes that are thoughtto structureRecent seabird systemsare functionsof geological processes operating at many temporal and spatial scales. For example, major oceanic currents,such as the North Pacific Gyre, are functionsof the relative positions of continentsand Antarcticgla- ciation,whereas regional air masses,submarine topography, and coastline shape affectlocal processes such as upwelling. I hypothesize that the long-termdevelopment of these abiotic processes has influencedthe relative diversityand communitycomposition of North Pacific seabirds. To explore this hypothesis,I divided the historyof North Pacific seabirds into seven intervalsof time. Using published descriptions,I summarized the tectonicand oceanographic events that occurred during each of these time intervals,and related changes in species diversityto changes in the physical environment.Over the past 95 years,at least 94 species of fossil seabirds have been described from marine deposits of the North Pacific. Most of these species are from Middle Miocene through Pliocene (16.0-1.6 Ma) sediments of southern California, although species from Eocene to Early Miocene (52.0-22.0 Ma) deposits are fromJapan, -

Louchart Et Al 2018 Bony Teeth

Bony pseudoteeth of extinct pelagic birds (Aves, Odontopterygiformes) formed through a response of bone cells to tooth-specific epithelial signals under unique conditions Antoine Louchart, Vivian De Buffrénil, Estelle Bourdon, Maitena Dumont, Laurent Viriot, Jean-Yves Sire To cite this version: Antoine Louchart, Vivian De Buffrénil, Estelle Bourdon, Maitena Dumont, Laurent Viriot, etal.. Bony pseudoteeth of extinct pelagic birds (Aves, Odontopterygiformes) formed through a response of bone cells to tooth-specific epithelial signals under unique conditions. Scientific Reports, Nature Publishing Group, 2018, 8 (1), 10.1038/s41598-018-31022-3. hal-02363288 HAL Id: hal-02363288 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02363288 Submitted on 21 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Bony pseudoteeth of extinct pelagic birds (Aves, Odontopterygiformes) formed Received: 4 May 2018 Accepted: 26 July 2018 through a response of bone cells Published: xx xx xxxx to tooth-specifc epithelial signals under unique conditions Antoine Louchart1,2, Vivian de Bufrénil3, Estelle Bourdon 4,5, Maïtena Dumont1,6, Laurent Viriot1 & Jean-Yves Sire7 Modern birds (crown group birds, called Neornithes) are toothless; however, the extinct neornithine Odontopterygiformes possessed bone excrescences (pseudoteeth) which resembled teeth, distributed sequentially by size along jaws. -

Frequency of Occurrence of Some Seabirds in Uruguay.-The Status of Certain Seabirds Is Little Known for Uruguay and the Eastern Coast of South America

510 THE CONDOR Vol. 64 a pair of these hawks was nesting nearby, as one of the birds was calling several times in the period when the falcon’s nest was under observation. No disgorged pellets were found underneath the nest tree. However, a large number of bleached ptarmigan bones were scattered below the nest. One ptarmigan sternum was partly covered by a thin crust of lichens, possibly indicating a long period of use of the nest site. It is interesting to speculate on the reason why the Gyrfalcon, customarily a cliff nester, would use the stick nest in the tree. Gyrfalcons in Alaska (Cade, Zoc. cit.) typically make use of old stick nests of other birds, especially Ravens’ nests on cliffs. In the Lookout Point area and westward to Hornby’s Bend, Ravens are not common. I know of only one breeding pair near Hornby’s Bend and the nest is located on a cliff. Only a few potential nesting sites on cliffs are available to the Gyrfalcon in the middle Thelon area. I know of only one short stretch of the Thelon where the river cuts through steep sandstone banks. Rough-legged Hawks and Peregrine Falcons, both of which nest on cliffs, are known to nest here and Gyrfalcons may also be found nesting on rock ledges of the steep banks. The tree nest under discussion was revisited on June 23, 1962. The nest was not occupied but a pair of gray Gyrfalcons had three young in a partly hollowed out witches’ broom in a white spruce nearby. -

Bulletin De L'institut Français D'études Andines 36 (2) | 2007

Bulletin de l'Institut français d'études andines 36 (2) | 2007 Varia Edición electrónica URL: http://journals.openedition.org/bifea/3778 DOI: 10.4000/bifea.3778 ISSN: 2076-5827 Editor Institut Français d'Études Andines Edición impresa Fecha de publicación: 1 agosto 2007 ISSN: 0303-7495 Referencia electrónica Bulletin de l'Institut français d'études andines, 36 (2) | 2007 [En línea], Publicado el 01 febrero 2008, consultado el 08 diciembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/bifea/3778 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/bifea.3778 Les contenus du Bulletin de l’Institut français d’études andines sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. IFEA Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Études Andines / 2007, 36 (2): 175-197 El registro de Pelagornithidae (Aves: Pelecaniformes) y la avifauna neógena del Pacífico sudeste El registro de Pelagornithidae (Aves: Pelecaniformes) y la avifauna neógena del Pacífico sudeste Martín Chávez* Marcelo Stucchi** Mario Urbina*** Resumen Se examina el registro neógeno de la extinta familia Pelagornithidae en las Formaciones Pisco (Perú) y Bahía Inglesa (Chile) en la costa pacífica de América del Sur. Se reportan nuevos especímenes pertenecientes al género Pelagornis, procedentes de los niveles Sacaco y Aguada de Lomas de la Formación Pisco, y del nivel fosfático de la Formación Bahía Inglesa. Asimismo se presentan elementos craneales y postcraneales de género indeterminado del nivel Montemar de la Formación Pisco y de la base de la misma, límite entre el nivel Cerro la Bruja y la Formación Chilcatay. Se compara el presente registro con los últimos antecedentes conocidos para la familia en el hemisferio sur. -

Flight Performance of the Largest Volant Bird

Flight performance of the largest volant bird Daniel T. Ksepkaa,b,1,2 aNational Evolutionary Synthesis Center, Durham, NC 27705; and bDepartment of Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695 Edited* by Paul E. Olsen, Columbia University, Palisades, NY, and approved June 13, 2014 (received for review November 14, 2013) Pelagornithidae is an extinct clade of birds characterized by bizarre based on combinations of viable mass estimates, aspect ratios, and tooth-like bony projections of the jaws. Here, the flight capabil- wingspans as described in Methods. ities of pelagornithids are explored based on data from a species with the largest reported wingspan among birds. Pelagornis sand- Systematic Paleontology ersi sp. nov. is represented by a skull and substantial postcranial Aves Linnaeus, 1758. Pelagornithidae Fürbringer, 1888. Pela- material. Conservative wingspan estimates (∼6.4 m) exceed theo- gornis Lartet, 1857. P. sandersi sp. nov. retical maximums based on extant soaring birds. Modeled flight properties indicate that lift:drag ratios and glide ratios for P. sand- Holotype. Charleston Museum (ChM) PV4768, cranium and right ersi were near the upper limit observed in extant birds and sug- mandibular ramus, partial furcula, right scapula, right humerus gest that pelagornithids were highly efficient gliders, exploiting lacking distal end, proximal and distal ends of the right radius, frag- a long-range soaring ecology. ments of ulna and carpometacarpus, right femur, tibiotarsus, fibula, tarsometatarsus, and single pedal phalanx (Fig. 1). Aves | fossil | Oligocene | paleontology | pseudotooth Etymology. sandersi honors retired Charleston Museum curator light ability in birds is largely governed by scaling effects, Albert Sanders, collector of the holotype. -

Abstracts 4Th SAPE Meeting 2004

1 SIXTH INTERNATIONAL MEETING OF THE SOCIETY OF AVIAN PALEONTOLOGY AND EVOLUTION Quillan, France 28th September – 3rd October, 2004 Sponsored by Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, UMR 5561 (Paléontologie analytique, Université de Bourgogne), and Association Dinosauria. ABSTRACTS Edited by Eric Buffetaut and Jean Le Loeuff 2 SYSTEMATIC REVISION OF SOUTH AMERICAN FOSSIL PENGUINS (SPHENISCIFORMES) Carolina Acosta Hospitaleche1,2 and Claudia Patricia Tambussi1,3 1Museo de La Plata, Paseo del Bosque s/n, 1900 La Plata, Argentina; 2CIC. ([email protected]);3CONICET. ([email protected]). A phylogenetic and morphometric analysis of South American fossil penguins has been done using skull and appendicular skeleton characters. Our current studies lead us to identify two groups substantially equivalent to those proposed originally by Simpson though abandoned later by himself after examining fossil New Zealand penguins: Palaeospheniscinae and Paraptenodytinae, and a third group belonging to a new subfamily Madrynornithinae. However, we have reevaluated both subfamilies, and when necessary we have amended the respective diagnoses. Only nine of the 35 previously named species are recognized, therefore the diversity would not have been so high as it was supposed. Herein we propose the following systematic arrangement: (1) PALAEOSPHENISCINAE Simpson, 1946 (Early Miocene of Argentina and Middle Miocene- Pliocene of Chile and Peru), characterized by humerus with a bipartite fossa tricipitalis, a high crus dorsale fossae, a laterocraneal fossa over the tuberculum ventrale and a sulcus ligamentaris transversus divided in two parts; tarsometatarsus with elongation index higher than two, a flattened metatarsal II, and a foramen vasculare proximale medialis only open in cranial side, including Eretiscus tonni (Simpson, 1981), Palaeospheniscus bergi Moreno and Mercerat, 1891, P. -

T.W.I.T.T. Newsletter

No. 226 APRIL 2005 T.W.I.T.T. NEWSLETTER I couldn’t resist this as I was searching the Internet. The B-58 Hustler meets the criteria for a flying wing since there are no tail surfaces. I don’t know about you, but I would certainly not like being on the receiving end of this thing coming at me with a full armament load. Photos were found at: http://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/systems/b-58-pics.htm T.W.I.T.T. The Wing Is The Thing P.O. Box 20430 El Cajon, CA 92021 The number after your name indicates the ending year and month of your current subscription, i.e., 0504 means this is your last issue unless renewed. Next TWITT meeting: Saturday, May 21, 2005, beginning at 1:30 pm at hanger A-4, Gillespie Field, El Cajon, CA (first hanger row on Joe Crosson Drive - Southeast side of Gillespie). TWITT NEWSLETTER APRIL 2005 THE WING IS TABLE OF CONTENTS THE THING ( ) President's Corner ............................................ 1 T.W.I.T.T. Next Month's Program....................................... 2 T.W.I.T.T. is a non-profit organization whose membership seeks March Meeting Recap........................................ 2 to promote the research and development of flying wings and other Letters to the Editor ........................................ 10 tailless aircraft by providing a forum for the exchange of ideas and Available Plans/Reference Material................ 11 experiences on an international basis. T.W.I.T.T. is affiliated with The Hunsaker Foundation, which is dedicated to furthering education and research in a variety of disciplines. -

Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area Paleontological Survey

Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area Paleontological Survey Alison L. Koch, Vincent L. Santucci, and Ted R. Weasma Technical Report NPS/NRGRD/GRDTR-04/01 ains Natio nt na ou l R e M c a r c e i a n t i o o n M A a t r e n a a S Paleontological Survey United States Department of the Interior - National Park Service - Geologic Resources Division Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area Paleontological Survey 29 Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area Paleontological Survey Alison L. Koch Vincent L. Santucci Ted R. Weasma Geologic Resources Division National Park Service Denver, Colorado NPS/NRGRD/GRDTR-04/01 2004 30 Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area Paleontological Survey 31 Dedicated to Norma Agusta Steiner and Margaret Llewellyn Koch 32 Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area Paleontological Survey 33 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................................................................................1 SIGNIFICANCE OF PALEONTOLOGICAL RESOURCES....................................................................................................................1 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND..........................................................................................................................................................2 ADMINISTRATIVE HISTORY...........................................................................................................................................................3 -

The Youngest Record of a Bony Toothed Bird

1 This is a postprint that has been peer reviewed and published in Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. The final, published version of this article is available online. Please check the final publication record for the latest revisions to this article. Boessenecker, R.W. and N.A. Smith. 2011. Latest Pacific basin record of a bony-toothed bird (Aves, Pelagornithidae) from the Pliocene Purisima Formation of California, U.S.A. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 31:652-657. 2 LATEST PACIFIC BASIN RECORD OF A BONY-TOOTHED BIRD (AVES, PELAGORNITHIDAE) FROM THE PLIOCENE PURISIMA FORMATION OF CALIFORNIA, U.S.A. ROBERT W. BOESSENECKER*, 1 and N. ADAM. SMITH2, 1Department of Earth Sciences, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana 59715 U.S.A., ([email protected]); 2Jackson School of Geosciences, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712 U.S.A. ([email protected]). *Corresponding author. INTRODUCTION The extinct Pelagornithidae, also known as pseudodontorns, are often referred to as the ‘bony– toothed’ birds, owing to the tooth-like projections that characterize the beaks of these pelagic birds. Pelagornithid fossil remains are known from every continent and have an age range spanning more than 55 million years from the Late Paleocene through the Middle Pliocene (Harrison, 1985; Olson, 1985; Mourer-Chauviré and Geraads, 2008, 2010). The systematic position of pelagornithids remains a contentious issue. Recent phylogenetic analysis recovered the pelagornithids as the sister taxon to Anseriformes (e.g., ducks and geese; Bourdon, 2005); however, this hypothesis contrasts with previous authors (Howard, 1957; Harrison and Walker, 1976; Olson, 1985) that considered pelagornithid affinities with Procellariiformes (e.g., albatrosses and petrels) or Pelecaniformes (e.g., pelicans and cormorants).