Definition of a Weed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Manage Weeds in Maize for High Yields

7. Integrated weed management Two or more of the above methods are used in combination to manage weeds with resultant ecological as well as social -economic benefits. REMEMBER How to manage weeds To achieve high and good quality yields, timeliness and cost effectiveness are crucial for every weed control in maize for high yields option. Kenya Agricultural Research Institute P.O. Box 57811-00200, NAIROBI. Tel: 254-20-4183301-20, FAX 254-20-4183344 Email: [email protected] Website: www. kari.org Compiled by: Mwangi, H.W. For more information contact: Good maize yields Centre Director, KARI Kabete P.O Box 14733-00800, Nairobi. Tel: (020) 4444144 KARI information brochure series / 8 /2008 Ksh. 20 Introduction 2. Hand weeding 5. Plant residue mulches Competition between maize and weeds can cause total This is done using various tools like hoes, knives and These are crop residues that are used to cover the crop loss depending on several weed factors. ploughs. Two weedings between the 2nd and 7th spaces between the growing crops. week after germination are often adequate for maize These factors include: depending on the agro eco zone. This method is not common due to a shortage of crop residues and destruction by termites. i) Type of weeds which may be This should be:- • Grass or broad leafed • First weeding at 2-3 weeks • Free living or parasitic 6. Chemical weed control (Herbicides) • Second one at 6-7 weeks after emergence. • Weed life cycle (Annual (1yr), Biennial (2yrs) These are chemicals that kill weeds. They exist in form perennial (>2yrs)) weed. -

Principles of Sustainable Weed Able Weed

PRINCIPLES OF SUSTAINABLE WEED MANAGEMENT FOR CROPLANDS AGRONOMY SYSTEMS SERIES Abstract: To some extent, weeds are a result of crop production, but to a larger extent they are a consequence of management decisions. Managing croplands according to nature’s principles will reduce weed problems. And while these principles apply to most crops, this publication focuses on agronomic crops such as corn, soybeans, milo, and small grains. The opportunities to address the root causes of weeds are not always readily apparent, and often require some imagination to recognize. Creativity is key to taking advantage of these opportunities and devising sustainable cropping systems that prevent weed problems, rather than using quick-fix approaches. Annual monoculture crop production generally involves tillage that creates conditions hospitable to many weeds. This publication discusses several alternatives to conventional tillage systems, including allelopathy, intercropping, crop rotations, and a weed- free cropping design. A Resources list provides sources of further information. By Preston Sullivan boundaries within which we operate and the NCAT Agriculture Specialist rules for success within those boundaries. September 2003 The “weed control” paradigm is reactive— it addresses weed First, Free Your Brain problems by using As Iowa farmer Tom Frantzen poetically states: various tools and tech- “Free your brain and your behind will follow.” nologies. “How am I What Tom is referring to is discovering new para- gonna get rid of this vel- digms. Joel Barker, author of Paradigms—The vet-leaf?” and “How do Business of Discovering the Future (1), defines a I control foxtail?” are re- paradigm as a set of standards that establish the active statements. -

Identifying & Managing Weeds in Gardens

Identifying & Managing Weeds in Gardens Todd Mervosh Valley Laboratory - Windsor The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station CAES- Spring Open House 2009 www.ct.gov/caes Definitions of WEED ‘Plant out of Place’ - any plant growing where it is not wanted. Plant with generally undesirable properties. Plant that spreads rapidly and competitively. “Plant that has mastered every survival skill except for learning how to grow in rows.” Doug Larson “A plant whose virtues have not yet been discovered.” Ralph Waldo Emerson “Is this a wildflower or a weed?” CAES- Spring Open House 2009 www.ct.gov/caes Field Violet / Field Pansy (Viola arvensis) CAES- Spring Open House 2009 www.ct.gov/caes CAES- Spring Open House 2009 www.ct.gov/caes WEEDS: NEGATIVES 1) Compete with crops / desirable plants for: • WATER, NUTRIENTS, SPACE, LIGHT 2) Reduce air flow in garden, keeping plants wetter & more prone to pathogens. 3) Can be alternate hosts for fungal diseases, or harbor insect pests. 4) Health Problems: Hay fever (ragweed), skin rashes (poison ivy). 5) Unattractive: Detract from beauty of garden or landscape planting. CAES- Spring Open House 2009 www.ct.gov/caes WEEDS: POSITIVES 1) Help protect soil from erosion. 2) Legumes (clovers, vetch) release nitrogen from root nodules into soil – add fertilizer. 3) Some weeds harbor beneficial insects. 4) Food sources for many animals. 5) Many weeds are edible for humans (purslane, lambsquarters, dandelion, etc.) 6) Some “weeds” are beautiful! CAES- Spring Open House 2009 www.ct.gov/caes Photo Credits Randy -

Invasive Plants in Your Backyard!

Invasive Plants In Your Backyard! A Guide to Their Identification and Control new expanded edition Do you know what plants are growing in your yard? Chances are very good that along with your favorite flowers and shrubs, there are non‐native invasives on your property. Non‐native invasives are aggressive exotic plants introduced intentionally for their ornamental value, or accidentally by hitchhiking with people or products. They thrive in our growing conditions, and with no natural enemies have nothing to check their rapid spread. The environmental costs of invasives are great – they crowd out native vegetation and reduce biological diversity, can change how entire ecosystems function, and pose a threat Invasive Morrow’s honeysuckle (S. Leicht, to endangered species. University of Connecticut, bugwood.org) Several organizations in Connecticut are hard at work preventing the spread of invasives, including the Invasive Plant Council, the Invasive Plant Working Group, and the Invasive Plant Atlas of New England. They maintain an official list of invasive and potentially invasive plants, promote invasives eradication, and have helped establish legislation restricting the sale of invasives. Should I be concerned about invasives on my property? Invasive plants can be a major nuisance right in your own backyard. They can kill your favorite trees, show up in your gardens, and overrun your lawn. And, because it can be costly to remove them, they can even lower the value of your property. What’s more, invasive plants can escape to nearby parks, open spaces and natural areas. What should I do if there are invasives on my property? If you find invasive plants on your property they should be removed before the infestation worsens. -

Estimated Cost of Production for Legalized Cannabis

WORKING P A P E R Estimated Cost of Production for Legalized Cannabis JONATHAN P. CAULKINS WR-764-RC July 2010 This product is part of the RAND working paper series. RAND working papers are intended to share researchers’ latest findings and to solicit informal peer review. They have been approved for circulation by RAND but have not been formally edited or peer reviewed. Unless otherwise indicated, working papers can be quoted and cited without permission of the author, provided the source is clearly referred to as a working paper. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. is a registered trademark. Estimated Cost of Production for Legalized Cannabis Jonathan P. Caulkins H. Guyford Stever Professor of Operations Research Carnegie Mellon University Heinz College & Qatar Campus RAND, Drug Policy Research Center Abstract This paper tries to estimate post-legalization production costs for indoor and outdoor cannabis cultivation as well as parallel estimates for processing costs. Commercial production for general use is not legal anywhere. Hence, this is an exercise in inference based on imperfect analogs supplemented by spare and unsatisfactory data of uncertain provenance. While some parameters are well grounded, many come from the gray literature and/or conversations with others making similar estimates, marijuana growers, and farmers of conventional goods. Hence, this exercise should be taken with more than a few grains of salt. Nevertheless, to the extent that the results are even approximately correct, they suggest that wholesale prices after legalization could be dramatically lower than they are today, quite possibly a full order of magnitude lower than are current prices. -

Weed Targeting Herbicide Management

EXTENSION EC708 Weed Targeting Herbicide Management Viacheslav I. Adamchuk, Extension Precision Agriculture Engineer Mark L. Bernards, Extension Irrigated Weed Specialist a major problem in summer annual crops like corn or George E. Meyer, Machine Vision Specialist sugarbeet may not even emerge when a winter annual Jerry A. Mulliken, Independent Crop Consultant crop like wheat is growing. RESOURCES ost producers use herbicides to manage weed Weeds exploit space not taken by the crop (inter- Minfestations. Generally, herbicides are applied row areas) and not disturbed by control methods such For more informa- at a uniform rate to the entire field. However, a as tillage or herbicides. Weeds vary in their response tion about precision uniform application may not be appropriate for all to different environmental cues and conditions that areas of a field. As precision agriculture technologies favor growth of one weed species over another. A few agriculture research, have developed, site-specific management of most studies have correlated landscape features and manage- education and dem- agricultural inputs, including herbicides, has become ment factors to the presence of weed patches. These onstration programs feasible. Differentiated application of herbicides is an characteristics include topography (or elevation), soil effective way to minimize herbicide costs, maximize pH, soil organic carbon (OC), fertility (nitrogen and at the University of weed control and prevent unnecessary environmental phosphorous), soil texture, field history, and herbicide Nebraska–Lincoln, waste. This circular provides basic guidance on site- use patterns. For example, topography, soil texture, specific weed management. and organic carbon can have a significant effect on visit the Web site at available moisture, which affects the ability of weeds http://precisionagriculture. -

Weed: Yellow Starthistle (Centaurea Solstitialis L.)

Weed: Yellow starthistle (Centaurea solstitialis L.) Family: Asteraceae (Sunflower family) Images: Brief Plant Description: (Summarized from Healy, E. and J. DiTomaso, Yellow Starthistle Fact Sheet, http://wric.ucdavis.edu/yst/biology/yst_fact_sheet.html) The seed leaves (cotyledons) are oblong to spatulate, 6-9 mm long and 3-5 mm wide, base wedge- shaped, tip +/- squared and glabrous. First few rosette leaves typically oblanceolate. Subsequent rosette leaves oblanceolate, entire to pinnate-lobed. Terminal lobes largest. Later rosette leaves to 15 cm long and are typically deeply lobed +/- to midrib and appear ruffled. Surfaces +/- densely covered with fine cottony hairs. Lobes mostly acute, with toothed to wavy margins. Terminal lobes +/- triangular to lanceolate. Mature plants have stiff stems, openly branched from near or above the base or sometimes not branched in very small plants. Stem leaves alternate, mostly linear or +/- narrowly oblong to oblanceolate. Margins smooth, toothed, or wavy. Leaf bases extend down the stems (decurrent) and give stems a winged appearance. Rosette leaves typically withered by flowering time. Largest stem wings typically to ~ 3 mm wide. Lower stem leaves sometimes +/- deeply pinnate-lobed. Foliage grayish- to bluish-green, densely covered with fine white cottony hairs that +/- hide thick stiff hairs and glands. Flower heads ovoid, spiny, solitary on stem tips, consist of numerous yellow disk flowers. Phyllaries palmately spined, with one long central spine and 2 or more pairs of short lateral spines. Insect- pollinated. Flowers mid-summer to fall. Corollas mostly 13-20 mm long. Involucre (phyllaries as a unit) ~ 12-18 mm long. Phyllaries +/- dense to sparsely covered with cottony hairs or with patches at the spine bases. -

Weed Control Guide for Ohio, Indiana and Illinois

Pub# WS16 / Bulletin 789 / IL15 OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION Tables Table 1. Weed Response to “Burndown” Herbicides .............................................................................................19 Table 2. Application Intervals for Early Preplant Herbicides ............................................................................... 20 Table 3. Weed Response to Preplant/Preemergence Herbicides in Corn—Grasses ....................................30 WEED Table 4. Weed Response to Preplant/Preemergence Herbicides in Corn—Broadleaf Weeds ....................31 Table 5. Weed Response to Postemergence Herbicides in Corn—Grasses ...................................................32 Table 6. Weed Response to Postemergence Herbicides in Corn—Broadleaf Weeds ..................................33 2015 CONTROL Table 7. Grazing and Forage (Silage, Hay, etc.) Intervals for Herbicide-Treated Corn ................................. 66 OHIO, INDIANA Table 8. Rainfast Intervals, Spray Additives, and Maximum Crop Size for Postemergence Corn Herbicides .........................................................................................................................................................68 AND ILLINOIS Table 9. Herbicides Labeled for Use on Field Corn, Seed Corn, Popcorn, and Sweet Corn ..................... 69 GUIDE Table 10. Herbicide and Soil Insecticide Use Precautions ......................................................................................71 Table 11. Weed Response to Herbicides in Popcorn and Sweet Corn—Grasses -

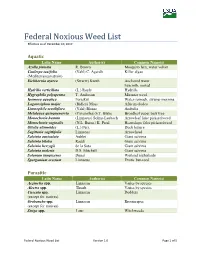

Federal Noxious Weed List Effective As of December 10, 2010

Federal Noxious Weed List Effective as of December 10, 2010 Aquatic Latin Name Author(s) Common Name(s) Azolla pinnata R. Brown Mosquito fern, water velvet Caulerpa taxifolia (Vahl) C. Agardh Killer algae (Mediterranean strain) Eichhornia azurea (Swartz) Kunth Anchored water hyacinth, rooted Hydrilla verticillata (L.) Royle Hydrilla Hygrophila polysperma T. Anderson Miramar weed Ipomoea aquatica Forsskal Water-spinach, swamp morning Lagarosiphon major (Ridley) Moss African elodea Limnophila sessiliflora (Vahl) Blume Ambulia Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cavanilles) S.T. Blake Broadleaf paper bark tree Monochoria hastata (Linnaeus) Solms-Laubach Arrowleaf false pickerelweed Monochoria vaginalis (N.L. Burm.) K. Presl Heartshape false pickerelweed Ottelia alismoides (L.) Pers. Duck lettuce Sagittaria sagittifolia Linnaeus Arrowhead Salvinia auriculata Aublet Giant salvinia Salvinia biloba Raddi Giant salvinia Salvinia herzogii de la Sota Giant salvinia Salvinia molesta D.S. Mitchell Giant salvinia Solanum tampicense Dunal Wetland nightshade Sparganium erectum Linnaeus Exotic bur-reed Parasitic Latin Name Author(s) Common Name(s) Aeginetia spp. Linnaeus Varies by species Alectra spp. Thunb. Varies by species Cuscuta spp. Linnaeus Dodders (except for natives) Orobanche spp. Linnaeus Broomrapes (except for natives) Striga spp. Lour. Witchweeds Federal Noxious Weed List Version 1.0 Page 1 of 5 Terrestrial Latin Name Author(s) Common Name(s) Acacia nilotica (L.) Willd. ex Delile Prickly acacia = Vachellia nilotica (L.) P.J.H. Hurter & (updated 3/21/2017) Ageratina adenophora (Sprengel) King & Crofton weed Ageratina riparia (Regel) King & H. Rob. Mistflower, spreading snakeroot Alternanthera sessilis (L.) R. Brown ex de Sessile joyweed Arctotheca calendula (L.) Levyns Capeweed Asphodelus fistulosus Linnaeus Onionweed (corrected 3/21/2107) Avena sterilis Durieu Animated oat, wild oat Carthamus oxyacantha M. -

An Alternative Perspective for the Theory of Biological Control

insects Perspective An Alternative Perspective for the Theory of Biological Control Nicholas J. Mills Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3114, USA; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-510-642-1711 Received: 12 September 2018; Accepted: 29 September 2018; Published: 2 October 2018 Abstract: Importation biological control represents the planned introduction of a specialist natural enemy from the region of origin of an invasive pest or weed. For this study, the author considered why attempts to develop a predictive theory for biological control have been misguided and what future directions might be more promising and effective. Despite considerable interest in the theory of consumer–resource population dynamics, such theory has contributed little to improvements in the success of biological control due to a focus on persistence and equilibrium dynamics rather than establishment and impact. A broader consideration of invasion biology in addition to population ecology offers new opportunities for a more inclusive theory of biological control that incorporates the demographic and genetic processes that more specifically address the establishment and impact of introduced natural enemies. The importance of propagule size and genetic variance for successful establishment, and of contributions to host population growth, relative population growth rates, interaction strength, and coevolution for suppression of host abundance are discussed as promising future directions for a theory of biological control. Keywords: pest; weed; importation; establishment; impact; demography; genetics 1. Introduction Biological control is an ecosystem service in which a pest or weed is effectively controlled through interactions with its natural enemies, and in many cases the natural enemies are insects [1]. -

FAR Focus 11– Weed Management for Maize

FAR Foundation ForFOCUSFOCUS Arable Research Issue 11 October 2013 Weed Management ISSUE for Maize 11 • Weed identification • The cost of weeds • Weed seeds • Non chemical weed management • Managing herbicides • Biosecurity ® ADDING VALUE TO THE BUSINESS OF ARABLE FARMING™ 2 FAR Focus 11 Weed Management for Maize Contents 1. Background ......................................................................... 2 2. Weed identification. ............................................................ 4 3. The cost of weeds ............................................................... 6 4. Weed seeds ......................................................................... 8 5. Non chemical weed management ................................... 13 6. Managing herbicides ........................................................ 15 7. Biosecurity ......................................................................... 26 References ............................................................................. 31 Acknowledgements .............................................................. 31 Appendix ................................................................................ 31 © Foundation for Arable Research (FAR) DISCLAIMER This publication is copyright to the Foundation for Arable Research and may not be reproduced or copied in any form whatsoever without written permission. This FAR Focus is intended to provide accurate and adequate information relating to the subject matters contained in it. It has been prepared and made available to -

Agriculture: a Glossary of Terms, Programs, and Laws, 2005 Edition

Agriculture: A Glossary of Terms, Programs, and Laws, 2005 Edition Updated June 16, 2005 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov 97-905 Agriculture: A Glossary of Terms, Programs, and Laws, 2005 Edition Summary The complexities of federal farm and food programs have generated a unique vocabulary. Common understanding of these terms (new and old) is important to those involved in policymaking in this area. For this reason, the House Agriculture Committee requested that CRS prepare a glossary of agriculture and related terms (e.g., food programs, conservation, forestry, environmental protection, etc.). Besides defining terms and phrases with specialized meanings for agriculture, the glossary also identifies acronyms, abbreviations, agencies, programs, and laws related to agriculture that are of particular interest to the staff and Members of Congress. CRS is releasing it for general congressional use with the permission of the Committee. The approximately 2,500 entries in this glossary were selected in large part on the basis of Committee instructions and the informed judgment of numerous CRS experts. Time and resource constraints influenced how much and what was included. Many of the glossary explanations have been drawn from other published sources, including previous CRS glossaries, those published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and other federal agencies, and glossaries contained in the publications of various organizations, universities, and authors. In collecting these definitions, the compilers discovered that many terms have diverse specialized meanings in different professional settings. In this glossary, the definitions or explanations have been written to reflect their relevance to agriculture and recent changes in farm and food policies.