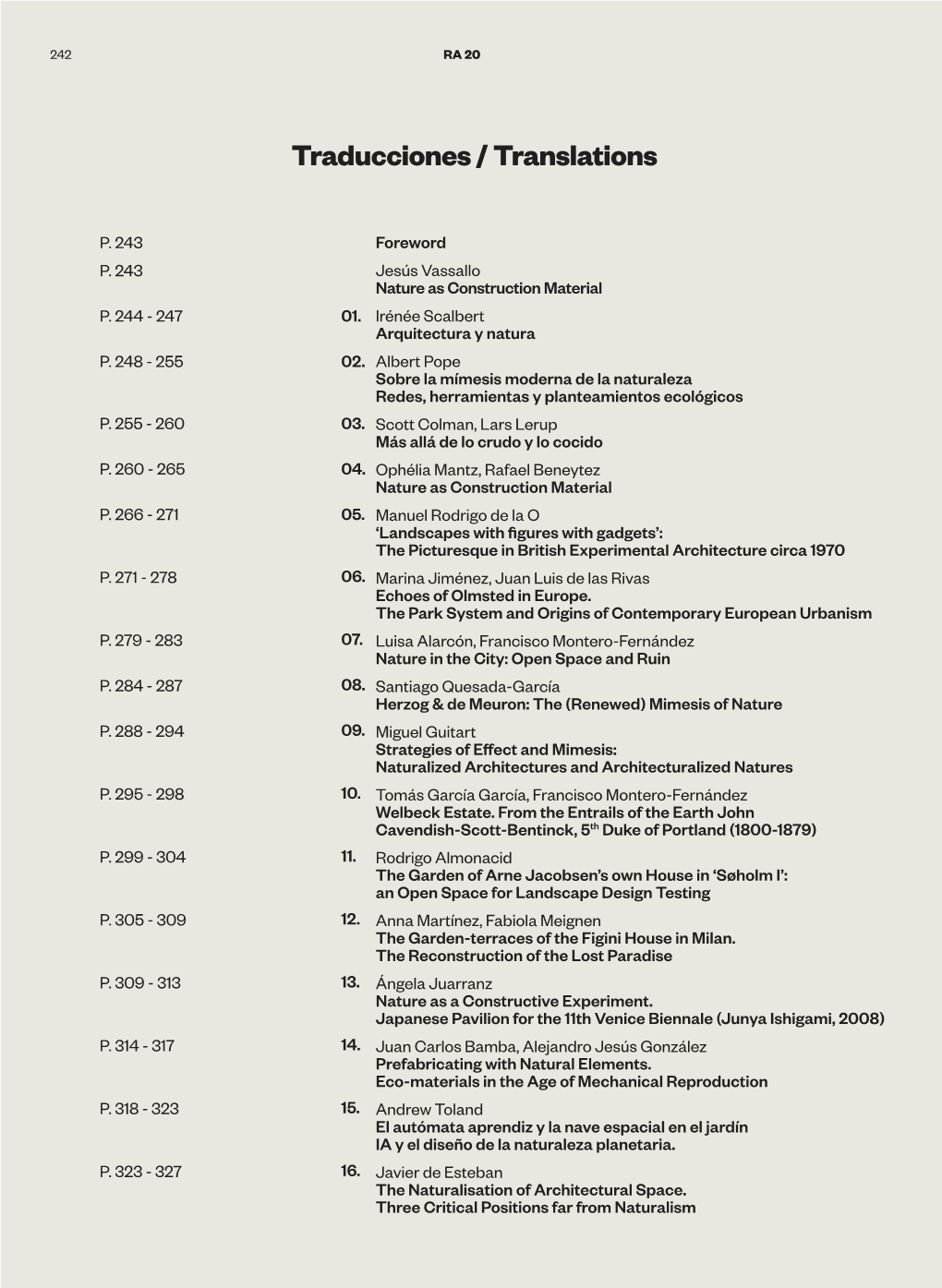

Traducciones / Translations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bobby Hutcherson, Vibraphonist with Coloristic Range of Sound, Dies at 75

Bobby Hutcherson, Vibraphonist With Coloristic Range of Soun... http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/17/arts/music/bobby-hutchers... http://nyti.ms/2bdO8F9 MUSIC Bobby Hutcherson, Vibraphonist With Coloristic Range of Sound, Dies at 75 By NATE CHINEN AUG. 16, 2016 Bobby Hutcherson, one of the most admired and accomplished vibraphonists in jazz, died on Monday at his home in Montara, Calif. He was 75. Marshall Lamm, a spokesman for Mr. Hutcherson’s family, confirmed the death, saying Mr. Hutcherson had long been treated for emphysema. Mr. Hutcherson’s career took flight in the early 1960s, as jazz was slipping free of the complex harmonic and rhythmic designs of bebop. He was fluent in that language, but he was also one of the first to adapt his instrument to a freer postbop language, often playing chords with a pair of mallets in each hand. He released more than 40 albums and appeared on many more, including some regarded as classics, like “Out to Lunch,” by the alto saxophonist, flutist and bass clarinetist Eric Dolphy, and “Mode for Joe,” by the tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson. Both of those albums were a byproduct of Mr. Hutcherson’s close affiliation with Blue Note Records, from 1963 to 1977. He was part of a wave of young artists who defined the label’s forays into experimentalism, including the pianist Andrew Hill and the alto saxophonist Jackie McLean. But he also worked with hard-bop stalwarts like the tenor saxophonist Dexter Gordon, and he later delved into jazz-funk and Afro-Latin grooves. Mr. Hutcherson had a clear, ringing sound, but his style was luminescent and 1 of 4 8/17/16, 2:43 PM Bobby Hutcherson, Vibraphonist With Coloristic Range of Soun.. -

Lmnop All Rights Reserved

Outside the box design. pg 4 Mo Willems: LAUGH • MAKE • NURTURE • ORGANISE • PLAY kid-lit legend. pg 37 Fresh WelcomeEverywhere I turn these days there’s a little bundle on the fun with way. Is it any wonder that babies are on my mind? If they’re plastic toys. on yours too, you might be interested in our special feature pg 27 on layettes. It’s filled with helpful tips on all the garments you need to get your newborn through their first few weeks. Fairytale holdiay. My own son (now 6) is growing before my very eyes, almost pg 30 magically sprouting out of his t-shirts and jeans. That’s not the only magic he can do. His current obsession with conjuring inspired ‘Hocus Pocus’ on page 17. You’ll find lots of clever ideas for apprentice sorcerers, including the all- © Mo Willems. © time classic rabbit-out-of-a-hat trick. Littlies aren’t left out when it comes to fun. Joel Henriques offers up a quick project — ‘Fleece Play Squares’ on page Nuts and bolts. pg 9 40 — that’s going to amaze you with the way it holds their interest. If you’re feeling extra crafty, you’ll find some neat things to do with those pesky plastic toys that multiply in your home on page 27. Bright is Our featured illustrator this month is the legendary Mo the word on Willems (page 37). If you haven’t yet read one of Mo’s books the streets (and we find that hard to believe) then here’s a good place this autumn. -

SUTRO HISTORIC DISTRICT Cultural Landscape Report

v 0 L u M E 2 SUTRO HISTORIC DISTRICT Cultural Landscape Report NATIONAL PARK SERVICE GOLDEN GATE NATIONAL RECREATION AREA II II II II II SUTRO HISTORIC DISTRICT II Cultural Landscape Report II II II II •II II II September 1993 II Prepared for United States Department of the Interior National Park Service II Golden Gate National Recreation Area II San Francisco, California Prepared by Land and Community Associates II Eugene, Oregon and Charlottesville, Virginia II In association with EDAW, Inc. II San Francisco, California II II II CREDITS II United States Department of the Interior II National Park Service Golden Gate National Recreation Area II Brian O'Neill, Superintendent Doug Nadeau, Chief, Resource Management & Planning II Nicholas Weeks, Project Manger, Landscape Architect Ric Borjes, Historical Architect Terri Thomas, Natural Resources Specialist/Ecologist II Jim Milestone, Ocean District Ranger Marty Mayer, Archeologist II Steve Haller, Historic Document Curator II Land and Community Associates Cultural Landscape Specialists II and Historical Landscape Architects J. Timothy Keller, FASLA, Principal-in-Charge II Robert Z. Melnick, ASLA, Principal-in-Charge Robert M. McGinnis, ASLA, Project Manager II Genevieve P. Keller, Senior Landscape Historian Katharine Lacy, ASLA, Historical Landscape Architect Liz Sargent, Landscape Architect II Julie Gronlund, Historian Frederick Schneider, Desktop Publishing II in association with II EDAW,lnc. II Landscape Architects and Planners Cheryl L. Barton, FASLA, Principal-in-Charge II Allen K. Folks, ASLA, Project Manager John G. Pelka, Environmental Planner II Misty March, Landscape Architect II II II II II II CONTENTS II 1 I MANAGEMENT SUMMARY II 1.1 Introduction and Project Background .. -

Vejviser for Gjentofte-Ordrup, Lyngby Og Søllerød Kommuner. 1898

Dette værk er downloadet fra Slægtsforskernes Bibliotek Slægtsforskernes Bibliotek er en del af foreningen DIS- Danmark, Slægt & Data. Det er et special-bibliotek med værker, der er en del af vores fælles kulturarv, blandt andet omfattende slægts-, lokal- og personalhistorie. Slægtsforskernes Bibliotek: http://bibliotek.dis-danmark.dk Foreningen DIS-Danmark, Slægt & Data: www.slaegtogdata.dk Bemærk, at biblioteket indeholder værker både med og uden ophavsret. Når det drejer sig om ældre værker, hvor ophavs-retten er udløbet, kan du frit downloade og anvende PDF-filen. Når det drejer sig om værker, som er omfattet af ophavsret, er det vigtigt at være opmærksom på, at PDF-filen kun er til rent personlig, privat brug. VEJVISER fo r Gjentofte —Ordrup, Lyngby og Søllerød Kommuner 1898 PETER SØRENSEN Eneste Guldmedaille Nørrevoldgade 22 for Pengeskabe i Danmark. Telefon 223 Midt for Ørstedsparken Telefon: O rd ru p 4 0 . Voldkvarterets Magasiners Filial (cand. pharm. Jacob U. Nielsen) C h a m p a g n e fra de Montigny & Co., Epernay Demi sec. Kr. 6,50, Carte blanche Kr. 5,50, Grand Sillery Kr. 4,50 Ikamfinol Tilberedte Oliefarver dtæ 'ber 2w£»l Dobbelt Roborans 1 Kr. pr. Fl. Kul, Gokes og Brænde ½ Fl. 2,25, V» Fl. 1,25 Vejviser for Gjentofte— Ordrup, Lynyby og Sollered Kommuner 1898 af G. Elley og L. Larsen, Hellerup. Pris: 2 Kr. Hellerup Bog- og Papirhandel ved Chr. Schmidt, Strandvej 151. Trykt hos Th. Nielsen, Kjobonhavn K. o Avertissementer. Lund & Lawerentz, Etablissement for ■ Qasbelysiiingsarti^Ier. ------------K— — Største Lager af (Saøhroner — Hamper — Hampetter (Saø=1kogeapparater — (Baø*£tegeovne $aø*1kakfcelovne — (Saø*Bat>eovne. -

[email protected] 2920 Charlottenlund

HOUSEKEEPING – PART TIME JOB June 2021 If you are living in Copenhagen or surrounding areas and are looking for part time work, then you just might be the person we are looking for. Skovshoved Hotel is a small and cozy hotel (22 rooms) located in the fishing village of Skovshoved (Gentofte municipality), just 20 minutes away from Copenhagen. (Bus 23 directly to the front door, nearest train station Ordrup St.) Together with the rest of the Housekeeping Team, you will be responsible for the daily cleaning of hotel rooms, common areas and meeting rooms as well as ordering goods and linen. It is preferable that you have a minimum of 1 year of experience from similar work. People with less experience are not dismissed though. We expect: • You have an eye for detail and are passionate about ensuring a high level of cleaning • You can maintain a high level of service and smile • You can work both weekdays and weekends • You are a team player • Speaks, reads and understands Danish(optional), as well as speaks and understands English • You have a minimum of 1 year experience from similar jobs We offer: • Education and training • Good and proper working conditions • A positive work environment with wonderful colleagues who are passionate about providing high service • Part-time contract (60 minimum hours guaranteed) If we have caught your interest, please send an E-mail with your application, resume and any references you may have, to our housekeeping manager Estera Turcu ([email protected]). Application deadline: 20.07.2021 Date of employment: As soon as possible If you have not received a reply from us within 10 days after your application, it means the position has been filled. -

Atlas Over Bygninger Og Bymiljøer Kulturarvsstyrelsen Og Gentofte Kommune Kortlægning Og Registrering Af Bymiljøer

GENTOFTE – atlas over bygninger og bymiljøer Kulturarvsstyrelsen og Gentofte Kommune Kortlægning og registrering af bymiljøer KOMMUNENUMMER KOMMUNE LØBENUMMER 157 Gentofte 33 EMNE Kystbanens stationer LOKALITET MÅL Charlottenlund, Ordrup og Klampenborg 1:20.000 REG. DATO REGISTRATOR Forår/sommer 2004 Robert Mogensen, SvAJ og Jens V. Nielsen, JVN Ortofoto, 1:20.000 DDO©,COWI CHARLOTTENLUND, ORDROP OG CHARLOTTENLUND, ORDROP OG KLAMPENBORG STATIONER KLAMPENBORG STATIONER Historisk kort. Målt 1899 og rettet 1914, 1:20.000. KMS 2 3 CHARLOTTENLUND, ORDROP OG CHARLOTTENLUND, ORDROP OG KLAMPENBORG STATIONER KLAMPENBORG STATIONER KLAMPENBORG Klampenborg BELLEVUE GALLOP- BANEN HVIDØRE Ordrup SKOVSHOVED HAVN TRAVBANEN CHARLOTTEN- Charlottenlund LUND SKOV CHARLOTTENLUND FORT HELLERUP HAVN Hellerup Stationsbygningernes udformning afspejler den tidsmæssige forskydning af banens udbygningsetaper. Mål 1:20.000 2 3 2 45 GÅRDVEJ GÅRDVEJ 2 2 CHARLOTTENLUND, ORDROP OG CHARLOTTENLUND, ORDROP OG KLAMPENBORG STATIONER KLAMPENBORG STATIONER Hellerup Station ligger i Københavns Kommune. Det gælder også stationsbygningerne, uanset at de Kulturhistorie & arkitektur sætter deres stærke præg på Ryvangs Allé’s nord- ligste stykke, som ligger i Gentofte Kommune, øst De fire jernbanestationer på strækningen mellem for stationen. Det bør nævnes, at den nuværende Hellerup og Klampenborg vidner dels om væsentlige Gentofte Station oprindeligt var identisk med den perioder i jernbanehistorien, dels om den interesse ældste station i Hellerup. man i tidens løb har vist jernbanens bygninger. Charlottenlund Station fik i 1898 den nuværende Ved anlægget af Nordbanen 1863-64, fra København meget store bygning. Arkitekt var Thomas Arboe til Helsingør over Hillerød, anlagde man også en (1836-1917). Han opførte over hele landet en række sidebane fra Hellerup til Klampenborg i forventning stationer med anvendelse af gule mursten i en saglig om, at udflugtstrafikken til skov og strand, herun- stil, med understregning af det stoflige i murværket. -

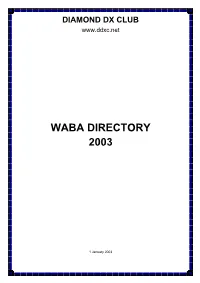

Waba Directory 2003

DIAMOND DX CLUB www.ddxc.net WABA DIRECTORY 2003 1 January 2003 DIAMOND DX CLUB WABA DIRECTORY 2003 ARGENTINA LU-01 Alférez de Navió José María Sobral Base (Army)1 Filchner Ice Shelf 81°04 S 40°31 W AN-016 LU-02 Almirante Brown Station (IAA)2 Coughtrey Peninsula, Paradise Harbour, 64°53 S 62°53 W AN-016 Danco Coast, Graham Land (West), Antarctic Peninsula LU-19 Byers Camp (IAA) Byers Peninsula, Livingston Island, South 62°39 S 61°00 W AN-010 Shetland Islands LU-04 Decepción Detachment (Navy)3 Primero de Mayo Bay, Port Foster, 62°59 S 60°43 W AN-010 Deception Island, South Shetland Islands LU-07 Ellsworth Station4 Filchner Ice Shelf 77°38 S 41°08 W AN-016 LU-06 Esperanza Base (Army)5 Seal Point, Hope Bay, Trinity Peninsula 63°24 S 56°59 W AN-016 (Antarctic Peninsula) LU- Francisco de Gurruchaga Refuge (Navy)6 Harmony Cove, Nelson Island, South 62°18 S 59°13 W AN-010 Shetland Islands LU-10 General Manuel Belgrano Base (Army)7 Filchner Ice Shelf 77°46 S 38°11 W AN-016 LU-08 General Manuel Belgrano II Base (Army)8 Bertrab Nunatak, Vahsel Bay, Luitpold 77°52 S 34°37 W AN-016 Coast, Coats Land LU-09 General Manuel Belgrano III Base (Army)9 Berkner Island, Filchner-Ronne Ice 77°34 S 45°59 W AN-014 Shelves LU-11 General San Martín Base (Army)10 Barry Island in Marguerite Bay, along 68°07 S 67°06 W AN-016 Fallières Coast of Graham Land (West), Antarctic Peninsula LU-21 Groussac Refuge (Navy)11 Petermann Island, off Graham Coast of 65°11 S 64°10 W AN-006 Graham Land (West); Antarctic Peninsula LU-05 Melchior Detachment (Navy)12 Isla Observatorio -

Halldór Laxness - Wikipedia

People of Iceland on Iceland Postage Stamps Halldór Laxness - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halldór_Laxness Halldór Laxness Halldór Kiljan Laxness (Icelandic: [ˈhaltour ˈcʰɪljan ˈlaxsnɛs] Halldór Laxness ( listen); born Halldór Guðjónsson; 23 April 1902 – 8 February 1998) was an Icelandic writer. He won the 1955 Nobel Prize in Literature; he is the only Icelandic Nobel laureate.[2] He wrote novels, poetry, newspaper articles, essays, plays, travelogues and short stories. Major influences included August Strindberg, Sigmund Freud, Knut Hamsun, Sinclair Lewis, Upton Sinclair, Bertolt Brecht and Ernest Hemingway.[3] Contents Early years 1920s 1930s 1940s 1950s Born Halldór Guðjónsson Later years 23 April 1902 Family and legacy Reykjavík, Iceland Bibliography Died 8 February 1998 Novels (aged 95) Stories Reykjavík, Iceland Plays Poetry Nationality Icelandic Travelogues and essays Notable Nobel Prize in Memoirs awards Literature Translations 1955 Other Spouses Ingibjörg Einarsdóttir References (m. 1930–1940) External links [1] Auður Sveinsdóttir (m. 1945–1998) Early years Laxness was born in 1902 in Reykjavík. His parents moved to the Laxnes farm in nearby Mosfellssveit parish when he was three. He started to read books and write stories at an early age. He attended the technical school in Reykjavík from 1915 to 1916 and had an article published in the newspaper Morgunblaðið in 1916.[4] By the time his first novel was published (Barn náttúrunnar, 1919), Laxness had already begun his travels on the European continent.[5] 1 of 9 2019/05/19, 11:59 Halldór Laxness - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halldór_Laxness 1920s In 1922, Laxness joined the Abbaye Saint-Maurice-et-Saint-Maur in Clervaux, Luxembourg where the monks followed the rules of Saint Benedict of Nursia. -

KUNSTLEX Juni 2020: Wolthers KUNSTLEXTM

KUNSTLEX juni 2020: TM Wolthers KUNSTLEX Udarbejdet af Anette Wolthers, 2020 Wolthers KUNSTLEXTM er udarbejdet i forbindelse med min research og skrivning af bogen: Kvindelige kunstnere i Odsherred gennem 100 år, publiceret af Odsherreds Kunstmuseums og Malergårdens Venner og Museum Vestsjælland i 2020. Bogen, der er på 248 sider, har også bidrag af museumsinspektør Jesper Sejdner Knudsen og formand for Venneforeningen Alice Faber. Bogen kan købes på de enkelte museer i Museum Vestsjælland eller kan bestilles på: [email protected] eller telefon 2552 8337. Den koster 299 kr plus forsendelsesomkostninger (ca. 77 kr.) Der var ikke plads i bogen til at alle mine ’fund og overvejelser’. Derfor har jeg samlet nogle af disse, så interesserede kan få adgang til denne viden i bredden og dybden, samt gå med ad de tangenter, der kan supplere bogens univers. Researcharbejdet til bogen Kvindelige kunstnere i Odsherred gennem 100 år er foregået 2016‐2019, og i denne proces opstod ideen om at lave mine mere eller mindre lange skrivenoter om et til et kunstleksikon. Så tænkt så gjort. Alle disse fund er nu samlet og har fået navnet Wolthers KUNSTLEX TM Man kan frit og gratis bruge oplysningerne i Wolthers KUNSTLEXTM med henvisning til kilden, forfatter, årstal samt placering: www.anettewolthers.dk Hvis der er brug for at citere passager fra Wolthers KUNSTLEXTM gælder de almindelige regler for copyright©, som er formuleret i Ophavsretsloven. Wolthers KUNSTLEXTM består af elementer af kunstviden fra ca. 1800‐tallet op til moderne tid og indeholder: 1. Korte biografer af overvejende danske kunstnere, deres familier, lærere, kolleger, kontakter og andre nøglepersoner i tilknytning til bogens 21 kunstnerportrætter samt enkelte tangenter ud og tilbage historien til vigtige personer – side 4 2. -

Jernbanenyheder Fra BL Sendt Mandag 9

Jernbanenyheder fra BL Sendt mandag 9. maj 2011 til http://john-nissen.dk/banesiden/ Offentliggøres på Banesiden Jernbanenyheder DEN DAGLIGE DRIFT (VEST) Ti 26/4 2011 CNL 40473 DSB EA 3022 har standsning i Kd 20.53-55½ med tog CNL 40473 (Kh-Basel SBB/Amsterdam Centraal). I Pa kommer Köf 285 og trækker EA 3022 væk fra spor 1. Dernæst tilkobles ES 64 U2-074. Standsning i Pa fandt sted kl. 21.57-22.19. (BL) Ma 2/5 2011 God nattesøvn (fortsat fra UDLAND) Standsningen i Hmb Hbf er kort: 4.11-13½! Der soves troligt videre til Flb. Landegrænsen krydses i Pagr (Padborg Grænse), og kl. 6. 13. er der ankomst i Pa. Køf 285 kommer ned i spor 2 for at hente ES 64 U2-017. Dernæst dukker DSB EA 3022. Afgang finder sted kl. 6.33. (BL) DEN DAGLIGE DRIFT (ØST) Fr 29/4 2011 Fredag Kan lige tilføje, at de tre IC4-togsæt stod i Nf, men ingen af dem var startet op, da jeg forlod byen klokken 7.36. Kommandoposten havde ikke hørt, om der skulle køres på Gedserbanen senere på dagen, men som sagt var der intet liv i eller omkring IC4’erne. DSB MZ 1425 holdt i ”Carlo”, sporet foran FC. På www.ing.dk kan man læse meget mere om IC4 skandalen – læs også lederen! TV2 ville i aftenens nyheder ud og køre IC4 fra Od. Toget ankom et kvarter forsinket pga. dørproblemer, der kun blev endnu værre i Od. Efter ca. 30 minutters ophold blev toget aflyst! Dette – sammenholdt med tilbageleveringen af de første dobbeltdækkere – gør efter min mening DSB’s materielsituation meget uholdbar – selv på kort sigt. -

Download the Publication Arne Jacobsen's Own House

BIBLIOGRAPHY Henrik Iversen, ‘Den tykke og os’, Arkitekten 5 (2002), pp. 2-5. ARNE JACOBSEN Arne Jacobsen, ‘Søholm, rækkehusbebyggelse’, Arkitektens månedshæfte 12 (1951), pp. 181-90. Arne Jacobsen’s Architect and Designer The Danish Cultural Heritage Agency, Gentofte. Atlas over bygninger og bymiljøer. Professor at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen (1956-1965). Copenhagen: The Danish Cultural Heritage Agency, 2004. He was born on 11 February 1902 in Copenhagen. Ernst Mentze, ‘Hundredtusinder har set og talt om dette hus’, Berlingske Tidende 10 October 1951. His father, Johan Jacobsen was a wholesaler. Félix Solaguren-Beascoa de Corral, Arne Jacobsen. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1989. Own House His mother, Pouline Jacobsen worked in a bank. Carsten Thau og Kjeld Vindum, Arne Jacobsen. Copenhagen: Arkitektens Forlag, 1998. He graduated from Copenhagen Technical School in 1924. www.arne-jacobsen.com Attended the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture in www.realdania.dk Copenhagen (1924-1927) Original drawings from the Danish National Art Library, The Collection of Architectural Drawings Strandvejen 413 He worked at the Copenhagen City Architect’s office (1927-1929) From 1930 until his death in 1971, he ran his own practice. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Peter Thule Kristensen, DPhil, PhD is an architect and a professor at the Institute of Architecture and JACK OF ALL TRADES Design at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation (KADK), where he is in charge of the post-graduate Spatial Design programme. He is also a core A total one of a kind, Arne Jacobsen was world famous. -

Passagerernes Tilfredshed Med Tryghed På Stationer

Passagerernes tilfredshed med tryghed på stationer NOTAT September 2019 Side 2 Indhold 1. Baggrund og formål 3 1.1 Om NPT og dataindsamlingen 4 2. Resultater 5 2.1 Stationer - opdelt på togselskaber 5 2.2 Alle stationer i alfabetisk rækkefølge 18 3. Om Passagerpulsen 31 Side 3 1. Baggrund og formål Passagerpulsen har i august og september 2019 fokus på stationer. Herunder blandt an- det passagerernes oplevelse af tryghed på stationerne. Dette notat indeholder en opgørelse over passagerernes tilfredshed med trygheden på tog- og metrostationer. Dataindsamlingen har fundet sted i forbindelse med dataindsam- lingen til Passagerpulsens Nationale Passager Tilfredshedsundersøgelser (NPT) i perio- den januar 2016 til og med september 2018. Notatet skal ses i sammenhæng med Passagerpulsens to øvrige udgivelser i september 2019: Passagerernes oplevelse af tryghed på togstationer1 Utryghed på stationer2 Notatet kan for eksempel anvendes til at identificere de stationer, hvor relativt flest passa- gerer føler sig trygge eller utrygge med henblik på at fokusere en eventuel indsats der, hvor behovet er størst. Vi skal i den forbindelse gøre opmærksom på, at oplevelsen af utryghed kan skyldes forskellige forhold fra sted til sted. For eksempel de andre personer, der færdes det pågældende sted eller de fysiske forhold på stedet. De to førnævnte rappor- ter belyser dette yderligere. 1 https://passagerpulsen.taenk.dk/bliv-klogere/undersoegelse-passagerernes-oplevelse-af-tryghed-paa-togstati- oner 2 https://passagerpulsen.taenk.dk/vidensbanken/undersoegelse-utryghed-paa-stationer Side 4 1.1 Om NPT og dataindsamlingen Resultaterne i dette notat er baseret på data fra NPT blandt togpassagerer i perioden ja- nuar 2016 til september 2018.