Development of Education in Tamil Nadu - a Historical Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PALANI.S CURRICULUM VITAE NSS Programme Officers(Ten Years)

CURRICULUM VITAE Career Objective To work on ambitious assignments in a stimulating environment that nurtures creative professional growth while being resourceful, innovative and flexible. Educational Qualification Ph.D: Madurai Kamaraj University (2015) Topic:"INEQUALITIES IN HEALTH CARE ACCESS AND PATTERN OF HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURE IN TAMIL NADU WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO MADURAI DISTRICT" PALANI.S M.phil:Madurai Kamaraj University (1991) Address: Associate Professor& Head Topic:CANARA BANK LOAN FOR DAIRY DEVELOPMENT WITH Dept. of Economics, SPECIAL REFERENCE TO USILAMPATTI BLOCK IN MADURAI DISTRICT. MTN College, Pasumalai M.A: History Madurai Kamaraj University (1995) Madurai-04. B.Ed. : Economics Madurai Kamaraj University (1993) M.A :EconomicsArul AnandarCollege, Madurai (1990) Mobile: 9894458382 B.A:PasumponMuthuramalingaThevar College, Usilampatti, Email: [email protected] Madurai, Tamilnadu. (1988) Teaching Experience( 25 Years) Personal Details: Assistant Professor (1995 -2000) DOB : 03/12/1965 MuthuramalingaThevar College, Usilampatti,Madurai, Tamilnadu Sex :Male Nationality :Indian At present working as an Associate Professor of Economics, MTN College, Religion : Hindu Madurai -04.(Since 2000) Marital Status :Married NSS programme officers(Ten Years) Personal Skills: 10 year (2000 – 2009). Interpersonal skills. Chief Superintendent: Compatible nature. Quick Learner 2013-2016 (Madurai Kamaraj University Semester Examinations And UPSC, SLET, Go-getter. RAILWAY,BANKING, TNPSC EXAMS were conducted. Hobbies: Foreign visit: 1. Thailand , 30/09/2016 Listening music. 2. Sharjah ,Dubai 9/11/2019 to 13/11/2019 Surfing Internet. Languages Known: Number of Awards Received English. Tamil. 1. Best presentor award :( Thailand) International Conference Areas of Interest: 2. Best Economist Award :( Goa) International Conference Development 3. Senior Economist Award :(Trichy) Association of Economist Tamil Nadu (2019) Economics Health Economics 4. -

Tamil Nadu State Research Report on Working Conditions of Elementary and Secondary School Teachers

NUEPA Research Reports Publications Series Teachers in the Indian Education System Tamil Nadu State Research Report on Working Conditions of Elementary and Secondary School Teachers Guide Dr. S. Kannappan Director, SCERT, Chennai Principal Researcher J. Inbaraj, M.A., M.Ed., M.Phil Reader, SCERT, Chennai Research Assistant S.Manivel, M.Sc. M.Ed., M.Phil Reader, SCERT, Chennai National University of Educational Planning and Administration New Delhi NRRPS/001(4/9)/2016 NRRPS/001/(4/9)/2016 NUEPA Research Reports Publications Series Teachers in the Indian Education System Tamil Nadu State Research Report on Working Conditions of Elementary and Secondary School Teachers (A NUEPA - SCERT Joint Project) Guide Dr. S. Kannappan Director, SCERT, Chennai Principal Researcher J. Inbaraj, M.A., M.Ed., M.Phil Reader, SCERT, Chennai Research Assistant S. Manivel, M.Sc., M.Ed., M.Phil Reader, SCERT, Chennai National University of Educational Planning and Administration New Delhi i © National University of Educational Planning and Administration, 2016 (Declared by Government of India under Section 3 of the UGC Act, 1956) June 2016 (PDF) Disclaimer: The research report has not been evaluated by any external expert, and also not edited by the PMU, NUEPA. The views and opinions expressed in the research report are those of the author(s)/editor(s) and should not be attributed to NUEPA. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronics, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission in writing from NUEPA. ii Acknowledgments First and foremost, the research team would like to convey their gratitude to the Ms. -

Annexure Government of India Ministry of Science & Technology, Department of Science & Technology List of Selected Stude

Annexure 12011/32/2010 INSPIRE (Tamil Nadu) Dated: 25 Oct 2018 Government of India Ministry of Science & Technology, Department of Science & Technology List of Selected Students under the INSPIRE Award Scheme for the Year 2018-19 Name of the State :Tamil Nadu No. of Sanctioned :3275 Sr. Name of Name of Name of Sub Name of the School Name of the selected Class Sex Category Name of Father UID No Ref Code No. Revenue Education District Student or Mother District District (Block/Tehsil/Zone etc.) 1 Ariyalur ARIYALUR Ariyalur PANCHAYAT UNION DURGADEVI S 7 F OBC SIVAKUMAR 18TN1467706 MIDDLE SCHOOL 2 Ariyalur ARIYALUR Ariyalur PANCHAYAT UNION DHANUSH G 8 M OBC GANACHANDRAN 18TN1467707 MIDDLE SCHOOL 3 Ariyalur Ariyalur Ariyalur GOVERNMENT HIGH S. REETA 10 F OBC SELVAKUMAR 18TN1467708 SCHOOL KANDARATHITHAM 4 Ariyalur Ariyalur Ariyalur GOVERNMENT HIGH S RETHINAM 9 M OBC SURIYARAJAN 18TN1467709 SCHOOL KANDARATHITHAM 5 Ariyalur Ariyalur Ariyalur GOVERNMENT HIGH G NARMATHA 8 F OBC GUNASEKAR 18TN1467710 SCHOOL KANDARATHITHAM 6 Ariyalur Ariyalur Ariyalur GOVERNMENT HIGH P. MANON 7 F OBC PALANISAMY 18TN1467711 SCHOOL KANDARATHITHAM 7 Ariyalur Ariyalur Ariyalur GOVERNMENT HIGH K PARIMALA 6 F OBC KANNAN 18TN1467712 SCHOOL KANDARATHITHAM Page 1 of 243 Sr. Name of Name of Name of Sub Name of the School Name of the selected Class Sex Category Name of Father UID No Ref Code No. Revenue Education District Student or Mother District District (Block/Tehsil/Zone etc.) 8 Ariyalur ARIYALUR Ariyalur GOVERNMENT Velmurugan E 8 M OBC Eruthayaraj 18TN1467713 HIGHER SECONDARY -

Policy Note of School Education Department

POLICY NOTE 2015-2016 CONTENTS I Policy 1 II Financial Outlay 10 III Polices and Schemes 1. Welfare Schemes 12 2. Elementary Education and 24 Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan 3. Secondary and Higher 121 Secondary Education and Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan 4. Matriculation Schools 184 5. Government Examinations 195 6. Non-formal and Adult 212 Education 7. Public Libraries 221 8. State Council of Educational 255 Research and Training 9. Teachers’ Recruitment Board 284 10. Tamilnadu Textbook and 296 Educational Services Corporation (i) LIST OF GRAPHS AND PICTURES SI. Details Page No. No. GRAPHS 1. Dropout Rate (Primary, Upper Primary & 2 Secondary) 2. Net Enrolment Rate (NER) 42 3. Dropout Rate (Primary & Upper Primary) 43 4. Completion Rate (CR) 44 5. Gender Perspective in enrolment - 45 Primary 6. Gender Perspective in enrolment - Upper 46 primary 7. Teacher Pupil Ratio (TPR) 47 8. Retention Rate 48 9. Out of School Children identified and 50 enrolled 10. Simplified Activity Based Learning 71 (SABL) 11. Active Learning Methodology (ALM) 73 12. Comparison of attendance of students 74 above 80% (2013-2014 & 2014-2015) 13. Comparison of Co-scholastic 75 performance of Class V (2013-2014 & 2014-2015) 14. Comparison of CCE Scholastic 75 performance Class VII (2013-2014 & 2014-2015) 15. Assessment - Primary - Comparison of 77 basic skills 16. Assessment - Upper Primary - 78 Comparison of basic skills 17. SLAS- Comparison of % of children 80 secured above 50 % - Class III 18. SLAS- Comparison of % of children 81 secured above 50 % - Class V 19. SLAS- Comparison of % of children 81 secured above 50 % - Class VIII 20. -

School Educational Status of Tamilnadu- a Case Study

Vol. 1 No.2 March 2013 ISSN : 2320 –2653 SCHOOL EDUCATIONAL STATUS OF TAMILNADU- A CASE STUDY Dr (Mrs) M. CHITRA Department Of Econometrics, Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai Dr. S. NAGARAJAMURUGAN Chief Educational Officer, Tamil Nadu Abstract Education is an engine of social and economic development. Investment in education as time and money will give the fruitful to the society then and there. The positive externality will be created if the output of education system is good. The supply side the government intervene in educational sector to create a positive externality in all aspects, in that sense in VirudhuNagar district (which is well known in internationally for its fireworks) is tested for its school educational status. The output of school education shown that the government sector played a vital role more than the private sector in VirudhuNagar District. Key words: School Education, S.S.L.C and Perception. Introduction Education is a critical invasive instrument for bringing about social, economic and political inclusion and a durable integration of people, particularly those excluded from the mainstream of any society. Indian education system was thrown open too all rich, poor and middle income classes, men and women, rural and urban population, and backward and non-backward segments of the population at all levels. As a consequence, there has been a veritable explosion in numbers – student numbers, institutions, and teachers. The returns to education may vary across individuals, regions, level and nature of education; in general, they are significantly higher for poor developing areas than for rich. Education is therefore his best social investment, given the synergies and the positive externalities that it generates for people in their well-being. -

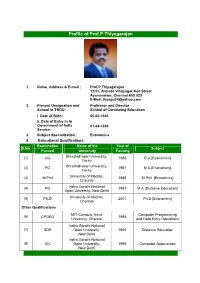

Profile of Prof.P.Thiyagarajan

Profile of Prof.P.Thiyagarajan 1. Name, Address & E-mail : Prof.P.Thiyagarajan 12/31, Ananda Vinayagar Koil Street Ayanavaram, Chennai-600 023 E-Mail: [email protected] 2. Present Designation and Professor and Director School in TNOU: School of Continuing Education i. Date of Birth: 05-03-1963 ii. Date of Entry in to Government of India 01-04-1989 Service: 3. Subject Specialization : Economics 4. Educational Qualifications: Examination Name of the Year of S.No. Subject Passed University Passing (1) UG Bhrathidhasan University, 1985 B.A.[Economics] Trichy (2) PG Bhrathidhasan University, 1987 M.A.[Economics] Trichy (3) M.Phil University of Madras, 1988 M.Phil. [Economics] Chennai (4) PG Indira Gandhi National 1997 M.A.[Distance Education] Open University, New Delhi (5) Ph.D University of Madras, 2001 Ph.D [Economics] Chennai Other Qualifications MIT-Campus, Anna Computer Programming (6) CPDEO 1988 University, Chennai and Data Entry Operations Indira Gandhi National (7) DDE Open University, 1993 Distance Education New Delhi Indira Gandhi National (8) CIC Open University, 1999 Computer Applications New Delhi 1 5. Employment History Appointed as Statistician by Directorate of Economic Research, Khadi and Village Industries Commission (KVIC), Irla Road, Vile Parle(West), Bombay-400056 vide Lr.No. EST/ECR/DSSC-I/88-89 dated 14/03/1989 and Joined in KVIC, State Office, Trivandrum -695001 on 01/04/1989. (Scale of Pay:Rs.1350-Rs.2200) Appointed as Investigator by Staff Selection Commission (SSC), Government of India, Ministry of Planning, Department of Statistics, National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO), New Delhi vide Lr.No. A.11010/1/Admn/TNN/89 dated 06/09/1989 and Joined in NSSO, Shastri Bhavan , Madras-600006 on 18/09/1989. -

History of Western Medical Education and Reservation in Tamilnadu

The International journal of analytical and experimental modal analysis ISSN NO:0886-9367 HISTORY OF WESTERN MEDICAL EDUCATION AND RESERVATION IN TAMILNADU R.PRAKASH , M.A. MPHIL., ASSISTANT PROFESSOR PG AND RESEARCH DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY SRI VASAVI COLLEGE, ERODE. TAMIL NADU, INDIA MOBILE: 9445108327 EMAIL: [email protected] ABSTRACT, Education is closely related with a nation’s development and health index is an important parameter in developing a nation. Health is not a luxury but fundamental need for a common man. This paper provides an insight into introduction and growth of Allopathic medical education in the Madras state by British and contribution of Dravidian parties to the growth of medical education in Tamil Nadu. This study also helps to know how the shifting of political scenarios and reservation policy of granting 69% to the backward communities has proved fruitful. Key Words ;Public health department-Social inequality-constitutional crisis- communal.G.O.-backward-Most Backward-Dravidar Munnetra kalagam-NEET-NEXT. The introduction of modern medicine in India was during advent of British. The first British hospital was established in 1639 A.D to treat sick solders of English East India Company. The first modern hospital in India was traced back to 1644 A.D at house of Mr. Cogan in Madras was rented for two pagodas per month (about Rs.5 today). This small rented house in 1664 private non-aided medical institutions all hospitals, dispensaries and clinics solely managed by private persons turned out to be a 105 year general hospital. After next 25 years, governer Elihu Yale gave the hospital premises in Fort St. -

13. Health and Family Welfare

13. HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE Health and Family Welfare 13 HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE c‰wh‹ msΫ ÃâmsΫ fhyK« f‰wh‹ fU¢ braš. - ÂU¡FwŸ 949 The habitudes of patient and disease, the crises of the ill: These must be learned leech think over well, then use his skill. - Thirukkural 949 Vision Tamil Nadu 2023 envisages that Tamil Nadu will be India’s leading State on social development and will have the highest Human Development Index (HDI) amongst all Indian States. Introduction even among those who are financially secured. High health care costs can lead to The health of the people in the State impoverisation or exacerbation of poverty. is an essential component of development, The importance of public provisioning of vital to the economic growth and internal quality health care at affordable costs and stability of the State. Assuring a minimal and provision of reliable heath services cannot be universal level of health care to the population underestimated. is a critical constituent of the development process. Human Development Index consists Health makes education possible of three components namely Education, Life and vice versa. Education of women delays Expectancy at Birth and Command over age at marriage, improves knowledge of Resources i.e. purchasing power parity. The contraceptives and enhances their status healthier the population, the more will be in society. Considering the above facts, the Index Value. Loss of health is most often the Government of Tamil Nadu has been irreversible and the potential loss of output bestowing more attention on female education for the individual cannot be compensated. -

Mapping Educational Policy Structures and Processes in Tamil Nadu

MAPPING EDUCATIONAL POLICY STRUCTURES AND PROCESSES IN TAMIL NADU Akila R. This study was made possible by a grant from the Sir Ratan Tata Trust. Educational Policy Research Series Volume I Number 1 April 2009 CONTENTS I. Setting the Context page 3 II. Educational Administration page 7 III. Government – NGO Partnership: The Way Forward page 28 IV. The Quest for Quality page 34 TABLES Table 1: Sex wise enrolment by stages 1991 – 2006 in Tamil Nadu, page 4 Table 2: Schools and Enrolment by type of Management in Tamil Nadu, 2005‐2006, page 15 FIGURES Figure 1: The Education Ladder in Tamil Nadu, page 12 Figure 2: Education Governing Bodies in Tamil Nadu, page 18 Figure 3: Organisation of Secretariat – School Education, page 22 Figure 4: Administrative Structure of School Education in Tamil Nadu, page 25 Figure 5: Structure and Functionaries in SSA, page 30 APPENDICES I. Some Important Events in the History of School Education Department in Tamil Nadu, page 39 II. District‐wise Schools by levels and types of management, Tamil Nadu, 2008‐09, page 41 III. National Curriculum Framework Guidelines, 2005, page 44 IV. Directory of Directorates under School Education in Tamil Nadu, page 47 2 I SETTING THE CONTEXT ʺI say without fear of my figures being challenged successfully, that today India is more illiterate than it was fifty or a hundred years ago, because the British administrators, when they came to India, instead of taking hold of things as they were, began to root them out. They scratched the soil and began to look at the root, and left the root like that, and the beautiful tree perished… ancient schools have gone by the board, because there was no recognition for these schools, and the schools established after the European pattern were too expensive for the people, and therefore they could not possibly overtake the thing. -

Access to Elementary Education in India Country Analytical Review

Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sussex Research Online Access to Elementary Education in India Country Analytical Review R. Govinda Madhumita Bandyopadhyay July 2008 National University of Educational Planning and Administration NUEPA The Consortium for Educational Access, Transitions and Equity (CREATE) is a Research Programme Consortium supported by the UK Department for International Development (DFID). Its purpose is to undertake research designed to improve access to basic education in developing countries. It seeks to achieve this through generating new knowledge and encouraging its application through effective communication and dissemination to national and international development agencies, national governments, education and development professionals, non-government organisations and other interested stakeholders. Access to basic education lies at the heart of development. Lack of educational access, and securely acquired knowledge and skill, is both a part of the definition of poverty, and a means for its diminution. Sustained access to meaningful learning that has value is critical to long term improvements in productivity, the reduction of inter-generational cycles of poverty, demographic transition, preventive health care, the empowerment of women, and reductions in inequality. The CREATE partners CREATE is developing its research collaboratively with partners in Sub-Saharan Africa and South -

School Dropouts of SC and ST Students in Chennai Corporation Schools

S. Peter, K.J. Raman and P. Ravilochanan School Dropouts of SC and ST Students… School Dropouts of SC and ST Students in Chennai Corporation Schools S. PETER, K.J. RAMAN AND P. RAVILOCHANAN The present study aims at culling out the various factors involved in making students from the Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribe (ST) categories to drop out of school. The study found that most of them attend school to have the noon meal and avail of monetary benefits like waiver on exam fees, free uniforms and books. As soon as they join secondary school, SC/ST students were forced to discontinue their studies due to various reasons as compared to other caste students. Due to this, SC/ST students find it difficult to start their own business and get employment only in unskilled jobs. The imperative step at this juncture would be ‘Education for All’ and to stress further ‘compulsory education at any cost for all’ and also to provide proper education for school dropouts. Reverend Dr. S. Peter and Dr. K.J. Raman are faculty with Loyola College, Chennai; and Dr. P. Ravilochanan is Faculty Member, A.M. Jain College, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. INTRODUCTION Venkata Subramanian (1979) analysed the economic aspects of growth of primary education in Tamil Nadu, while Sharma (1983) made an attempt to study the factors, which are responsible for the low enrolment in the schools and subsequent high dropout rates. Seetharamu and Usha Devi (1985) identified various problems of participation in low and high school dropout areas in different regions of Karnataka state. -

Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR 2015 - 16)

Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR 2015 - 16) Submitted to NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL Bangalore – 560 072. By Internal Quality Assurance Cell (IQAC) SENGAMALA THAYAAR EDUCATIONAL TRUST WOMEN’S COLLEGE (Affiliated to Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli) Recognized by UGC under section 2(f) & 12(B) (NAAC accredited ‘A’ Grade with CGPA 3.45 / 4.00) SUNDARAKKOTTAI, MANNARGUDI – 614 016. TIRUVARUR DISTRICT, TAMILNADU. AQAR 2015-2016 – NAAC, Bangalore The Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) of the IQAC Part – A AQAR for the year 2015-2016 1. Details of the Institution 1.1 Name of the Institution SENGAMALA THAYAAR EDUCATIONAL TRUST WOMEN‟S COLLEGE 1.2 Address Line 1 Main Road Sundarakkottai Village Address Line 2 Mannargudi City/Town Tamil Nadu State Pin Code 614 016 Institution e-mail address [email protected] / [email protected] 04367-255405 Contact Nos. Name of the Head of Dr.S.Amudha, M. Com., M.Phil., M.B.A., Ph.D. the Institution Tel. No. with STD Code 04367- 255405 Mobile 9443703331 [Type text] Page 1 AQAR 2015-2016 – NAAC, Bangalore Name of the IQAC Dr. R. Saravanamuthu M.Sc., M.Phil., Ph.D. Co-ordinator Mobile 9842618181 [email protected] IQAC e-mail address 1.3 NAAC Track ID TNCOGN19382 OR 1.4 NAAC Executive EC (SC)/05/A&A/085 dated 03.03.2015 Committee No. & Date 1.5 Website address www.stet.edu.in Web-link of the AQAR http://stet.edu.in/AQAR /AQAR15-16.pdf 1.6 Accreditation Details YEAR OF VALIDITY Sl. No. CYCLE GRADE CGPA ACCREDITATION PERIOD 1 1st Cycle A 3.45 03.03.2015 02.03.2020 2 2nd Cycle 3 3rd Cycle 4 4th Cycle 1.7 Date of Establishment of IQAC : DD/MM/YYYY 20.06.2011 1.8 Details of the previous year’s AQAR submitted to NAAC after the latest Assessment and Accreditation by NAAC i.