Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wadaiko in Japan and the United States: the Intercultural History of a Musical Genre

Wadaiko in Japan and the United States: The Intercultural History of a Musical Genre by Benjamin Jefferson Pachter Bachelors of Music, Duquesne University, 2002 Master of Music, Southern Methodist University, 2004 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2010 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences This dissertation was presented by Benjamin Pachter It was defended on April 8, 2013 and approved by Adriana Helbig Brenda Jordan Andrew Weintraub Deborah Wong Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung ii Copyright © by Benjamin Pachter 2013 iii Wadaiko in Japan and the United States: The Intercultural History of a Musical Genre Benjamin Pachter, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 This dissertation is a musical history of wadaiko, a genre that emerged in the mid-1950s featuring Japanese taiko drums as the main instruments. Through the analysis of compositions and performances by artists in Japan and the United States, I reveal how Japanese musical forms like hōgaku and matsuri-bayashi have been melded with non-Japanese styles such as jazz. I also demonstrate how the art form first appeared as performed by large ensembles, but later developed into a wide variety of other modes of performance that included small ensembles and soloists. Additionally, I discuss the spread of wadaiko from Japan to the United States, examining the effect of interactions between artists in the two countries on the creation of repertoire; in this way, I reveal how a musical genre develops in an intercultural environment. -

Copyright by Angela Kristine Ahlgren 2011

Copyright by Angela Kristine Ahlgren 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Angela Kristine Ahlgren certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Drumming Asian America: Performing Race, Gender, and Sexuality in North American Taiko Committee: ______________________________________ Jill Dolan, Co-Supervisor ______________________________________ Charlotte Canning, Co-Supervisor ______________________________________ Joni L. Jones ______________________________________ Deborah Paredez ______________________________________ Deborah Wong Drumming Asian America: Performing Race, Gender, and Sexuality in North American Taiko by Angela Kristine Ahlgren, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Dedication To those who play, teach, and love taiko, Ganbatte! Acknowledgments I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to each person whose insight, labor, and goodwill contributed to this dissertation. To my advisor, Jill Dolan, I offer the deepest thanks for supporting my work with great care, enthusiasm, and wisdom. I am also grateful to my co-advisor Charlotte Canning for her generosity and sense of humor in the face of bureaucratic hurdles. I want to thank each member of my committee, Deborah Paredez, Omi Osun Olomo/Joni L. Jones, and Deborah Wong, for the time they spent reading and responding to my work, and for all their inspiring scholarship, teaching, and mentoring throughout this process. My teachers, colleagues, and friends in the Performance as Public Practice program at the University of Texas have been and continue to be an inspiring community of scholars and artists. -

Saturday, January 27,1990 at Fioo Pm

f i WORLD-MUSIC CONCERT Music of India, China and Japan Saturday, January 27,1990 at FiOO pm Convocation Hall, Arts Building University of Alberta Q o V y WORLD-MUSIC IS YOUR MUSIC! "The "culturalpot-pourri" which is Canada....." "Canada is a rich collage ofcultural diversity....." "Life in Alberta is enriched by its diverse cultural heritage....." "Cultural diversity b maintained through the desire to assimilate various ethnic groups while maintaining their individuality and preserving their heritage....." Canadians hear such statements daily. It is, in fact, a principle by which Canadians define themselves. Now this desire is given expression in the third of a series of annual World-Music concerts. Ethnic musicians from Edmonton and area have been invited to participate in an evening of ethnic music presented under the auspices of the Department of Music. The World-Music concerts honour Moses Asch and the Asch family on the occasion of their donation of the complete catalogue of Folkways recordings henceforth known as the Moses and Frances Asch Collection. Moses Asch was the founder of Folkways Records, the world's largest commercially available collection of folk and tribal music. The objectives of the World-Music concert series are manifold. First, the commitment of the Department of Music to scholarly research in ethnomusicology - the study of ethnic musics - has been demonstrated through the appointment of a full-time member of faculty whose teaching and research responsibilities are dedicated to the furtherance of knowledge in the field. Second, the World-Music concert series will provide a forum for exposure of ethnic music to Edmonton and area audiences. -

Taikoza: Japanese Taiko Drums & Dance

Presents Taikoza: Japanese Taiko Drums & Dance Friday, February 16, 2007 10:00AM Concert Hall Study Guides are also available on our website at www.fineartscenter.com - select “For School Audiences” under “Education” in the right column, then Select Resource Room. The Arts and Education Program of the Fine Arts Center is sponsored by About Taikoza Taikoza is a Japanese Taiko drum group that uses the powerful rhythms of the Taiko drums to create an electrifying energy that carries audiences in a new dimension of excitement. The taiko is a large, barrel-like drum that can fill the air with the sounds of rolling thunder. Drawing from Japan's rich tradition of music and performance, Taikoza has created a new sound using a variety of traditional instruments. In addition to drums of assorted sizes, Taikoza performers also play the shakuhachi and the fue (both bamboo flutes) and the koto (a 13 string instrument). Taikoza was formed in New York City by members of Ondekoza (the group that started the modern day renaissance of Japanese Taiko in the 1960’s and introduced Taiko to the world). Taikoza’s love for taiko drumming transcends national boundaries bringing new energy to this ancestral form. Taikoza has performed in Europe, and Asia. The group has also appeared on the History Channel and The Last Samurai DVD set. Taikoza’s goal is to educate people about the exciting art form of Taiko and introduce them to Japanese culture. Taikoza was formed in 1995 by some of the original members of Ondekoza, the group responsible for the Taiko renaissance in the 1960’s. -

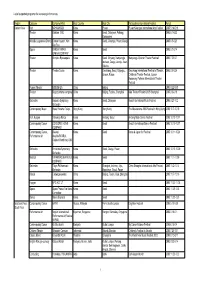

List of Supported Programs for Overseas Performances Region

List of supported programs for overseas performances Region Category Company/Artist Host Country Host City Participating International Festival Period Eastern Asia Noh NOHGAKUZA Korea Pusan Pusan Kwangan International Arts Festival 2005.5.14-5.18 Theater Gekidan 1980 Korea Seoul, Ddaejeon, Pohang, 2005.6.1-6.22 Gwangyang Wadaiko (Japanese Drum) Eitetsu Hayashi, Kim Korea Seoul, Gwangju, Pusan, Daegu 2005.6.5-6.20 Duk Soo Opera KANSAI NIKIKAI Korea Seoul 2005.6.7-6.14 OPERA COMPANY Theater Shinjuku Ryozanpaku Korea Seoul, Miryang, Namyangju, Namyangju Openair Theater Festival 2005.7.25-9.7 Incheon, Daegu, Jeonju, Asan, Sokcho Theater Theatre Douke Korea Geochang, Seoul, Uijongbu, Geochang International Festival of Theater, 2005.8.9-8.26 Suwon, Pusan Children's Theater Festival, Suwon Hwaseong Fortress International Theater Festival Puppet Theater MUSUBI-ZA China Beijing 2005.8.22-8.30 Theater Dogeza drama company China Beijing, Fuzhou, Shanghai Asia Theater Festival 2005 Shanghai 2005.9.9-9.18 Orchestra Sapporo Symphony Korea Seoul, Ddaejeon Seoul International Music Festival 2005.9.27-10.2 Orchestra Contemporary Music Brass Extreme Tokyo Hong Kong Hong Kong The Musicarama 2005 Festival in Hong Kong 2005.10.7-10.10 Noh, Kyogen Tetsunojo Kanze Korea Andong, Seoul Andong Mask Dance Festival 2005.10.10-10.17 Contemporary Dance CONDORS, HONG Korea Seoul Seoul International Dance Festival 2005.10.10-10.17 COMPANY Contemporary Dance, Biwakei, Korea Seoul Korea & Japan Art Festival 2005.10.11-10.24 Performance Art AbeAbe"M"ARIA, Gokiburi Kombinat, -

Cd List 2007

CD LIST 2007 JAPANESE CD ENCYCLOPAEDIA TRADITIONAL JAPANESE MUSIC/ Crossover genres CD nr. Title Artist (Genre) 1001 ”New” Ondekoza 1002 Ondekoza Ondekoza 1003 Poetry of Japan The Cleveland Orchestra Sinfonietta 1004 Fujiyama Odekoza 1005 Nihon no Oto 1006 Japanese melodies Stern, Rampal and Yo-Yo Ma 1007 Hana/Shakuhachi Nihon no Shijyou K. MIYATA / K. YAMAMOTO / Royal Pops 1008 Tsugaru Shamisen ~ Tsugaru Jyongara Bushi ~ Michiya MITSUHASHI 1009 Koto. Oiwai no shirabe Various artists (Koto music - Japanese long zither) 1010 Bon Odori Ketteiban ~ Odotte Tanoshii (Traditional folk dance) 1011 Nihon no Seigaku / Composer Series Rentaro TAKI 1012 The Art of the Koto, vol. 1: Celestial Harmonies Nanae YOSHIMURA (Koto music) 1013 On a Treetop Nanae YOSHIMURA (Koto music) 1014 Taqsim Nanae YOSHIMURA (Koto music) 1015 Voices Phantasma, Flame Nanae YOSHIMURA (Koto music) 1016 Best Take Nanae YOSHIMURA (Koto music) 1017 Berlin concert: The Quiet Ages 2000 Eitetsu Hayashi (drums, incl. Taiko) 1018 Gagaku: Court Music of Japan Tokyo Gakuso (gagaku) 1019 Yukyo: Taiko, New Sound from Tradition Furyudaigaku-Matsurishu 1020 Nagauta; Songs accompanied by shamisen and drums Various artists (Nagauta) 1021 Biwa: Traditional string instrument Various artists (Biwa music - Japanese lute) 1022 Edo Kiyari: Tokyo labour songs from Edo period Various artists (vocal only) 1023 Kiyomoto: Reciting stories accompanied by Shamisen Various artists 1024 Tokiwazu: Shamisen music Various artists 1025 Yokyoku: Vocal part of Noh music Various artists 1026 Zokkyoku: Folk -

Louder and Faster

LOUDER AND FASTER PAIN, JOY, AND THE BODY POLITIC IN ASIAN AMERICAN TAIKO DEBORAH WONG Luminos is the Open Access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org AMERICAN CROSSROADS Edited by Earl Lewis, George Lipsitz, George Sánchez, Dana Takagi, Laura Briggs, and Nikhil Pal Singh Louder and Faster Louder and Faster Pain, Joy, and the Body Politic in Asian American Taiko Deborah Wong UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2019 by Deborah Wong This work is licensed under a Creative Commons [CC-BY-NC-ND] license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses. Suggested citation: Wong, D. Louder and Faster: Pain, Joy, and the Body Politic in Asian American Taiko. Oakland: University of California Press, 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/luminos.71 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Wong, Deborah Anne, author. Title: Louder and faster : pain, joy, and the body politic in Asian American taiko / Deborah Wong. -

Japan's Premier Taiko Drummer Eitetsu Hayashi on Tour Across

TORONTO FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: JUNE 1, 2018 Japan’s premier Taiko drummer Eitetsu Hayashi on tour across Canada #EitetsuHayashi performances celebrate #JapanCanada90 diplomatic relations Dates: Friday, August 10th, 2018 to Saturday, August 25th, 2018 Cities: Calgary, Vancouver, Ottawa and Toronto Performers: Eitetsu Hayashi and EITETSU FU-UN no KAI (Shuichiro Ueda, Mikita Hase, Makoto Tashiro and Tasuku Tsuji) The Japan Foundation, Toronto - In the spirit of celebrating the 90th Anniversary of Canada-Japan Diplomatic relations, the Japan Foundation presents Eitetsu Hayashi: Japanese TAIKO Drum Concert Tour with Eitetsu FU-UN no KAI. Japan’s premier solo taiko drummer, Eitetsu Hayashi, will embark on tour across Canada this summer. The legendary musician will be on tour together with his ensemble of young drummers, the FU-UN no KAI ensemble, with concerts taking place in Calgary, Vancouver, Ottawa and Toronto. The sound of the taiko knows no boundaries, and without a doubt, will resonate with Canadian audiences across the country. The Eitetsu Hayashi: Japanese TAIKO Drum Concert Tour with Eitetsu FU-UN no KAI will give people in Canada a rare chance to experience the musical creativity of an artist at the forefront of taiko drumming in Japan. About the tour Eitetsu Hayashi: Japanese TAIKO Drum Concert Tour with Eitetsu FU-UN no KAI will perform at premier performance venues across Canada starting in Calgary, Vancouver, Ottawa and ending 2 Bloor Street East, Suite 300 | Toronto, ON | M4W 1A8 416-966-1600 | www.jftor.org TORONTO in Toronto. Eitetsu Hayashi will also be participating in taiko workshops in each of the cities to share his expertise with local Canadian taiko groups. -

Made in Japan: Kumi-Daiko As a New Art Form Anna Marie Viviano University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2013 Made in Japan: Kumi-Daiko as a New Art Form Anna Marie Viviano University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Viviano, A. M.(2013). Made in Japan: Kumi-Daiko as a New Art Form. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/1660 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MADE IN JAPAN: KUMI-DAIKO AS A NEW ART FORM by Anna Viviano Bachelor of Music Vanderbilt University, 2007 Master of Music University of Maryland, 2010 ________________________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2013 Accepted by: Scott Herring, Major Professor Chairman, Examining Committee Reginald Bain, Committee Member Julie Hubbert, Committee Member Scott Weiss, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies DEDICATION I dedicate this paper to the most awesome husband in the world, Joseph Viviano. Without his support and encouragement I would have never gotten to this point in my musical career. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I am grateful to Dr. Scott Herring, who has been an excellent teacher and mentor throughout my studies at the University of South Carolina. Without his encouragement and aid I would not have been able to finish this program so smoothly from eight hours away. -

Thesis in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

TaikOz – Performing Australian Taiko Felicity Clark A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sydney Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney February 2018 Abstract TaikOz have for twenty years pioneered taiko and shakuhachi music in Australia to international acclaim. Taiko, the Japanese word for drum, is also the name of a multifaceted collection of Japanese-looking drumming cultures popular worldwide since the 1960s. As taiko players bolster the legitimacy of their activities with tangential histories of older, even imagined, Japanese art forms, Australian musicians TaikOz spend considerable effort trying to match their practice to this discourse while also challenging its validity. Stuck fitting in as outsiders, TaikOz head taiko proficiency globally and collaborate with the pioneers of the staged genre. By assessing several TaikOz compositions and collaborative projects, and through compilation of all print media mentions of TaikOz, this thesis demonstrates that the stories told about taiko and TaikOz are skewed. Through interviews and fieldwork, TaikOz revealed the ways they work, but how their processes are often unrecognised or misinterpreted. This thesis investigates where communicative errors are occurring and promotes that using a template of performativity might yield more honest renderings of this inter-cultural artistic exercise into text. 1 Originality statement This is to certify that • the thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD • due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used • the thesis is less than 100,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps, bibliographies and appendices. Felicity Clark 2 Acknowledgements A wide circle of people supported this thesis with conversations, feedback and scholarly input. -

Development and Support of Taiko in the United States

DEVELOPMENT AND SUPPORT OF TAIKO IN THE UNITED STATES Paul J. Yoon, Ph.D. 1 2/10/2007 Edited Yoon Figure 1: Members of San Francisco Taiko Dojo performing at the Japantown Peace Plaza. The taiko, Japanese for drum, is variously spoken of as an instrument that was used in ancient Japan to drive pestilence away from planted fields or for encouraging troops engaged in battle. Village boundaries were said to be demarcated by the point at which one could no longer hear the taiko being played from the village’s center. These statements, whether real or fable, offer important characterizations about the taiko that continue to resonate today. For one, by virtue of size, the taiko is a loud instrument. The average nagado taiko, as seen in Figure 1, is between eighteen and twenty-four inches in diameter and is struck with a pair of bachi (Japanese for any stick or plectrum used with a musical instrument) fifteen inches in length or greater. Playing taiko typically demands strength and rigorous training. The taiko, as an art form, is also closely associated with communities and the places they inhabit. The booming sound of the taiko has become a staple of Japanese and Asian American festivals, Japanese American Buddhist temples, and concerts halls across the United States. For many, taiko, as instrument and art form, has come to symbolize the Japanese and Asian American experience. For all its ancient underpinnings, the art form of taiko has a relatively contemporary provenance and differs significantly from the traditional contexts of Japanese drumming. Taiko drums are 2 traditionally supporting instruments within an orchestra, giving rhythmic support to melodic instruments or singers. -

Taiko As Performance: Creating Japanese American Traditions

The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 12 (2001) Taiko as Performance: Creating Japanese American Traditions Hideyo KONAGAYA INTRODUCTION The acoustics, rhythms, and visual symbols of taiko illuminate the cul- turally specific values and beliefs of Japanese Americans, mirroring their ties to Japanese traditions but transcending ethnic boundaries as well.1 Taiko has prevailed as the most powerful mode of folk expression among Japanese Americans since the late 1960s, surviving acculturation of the ethnic community into American society. Sansei, the third generation Japanese Americans, discovered new meanings in this form of the Japanese folk tradition and have transformed it into an effective medi- um of self-expression. The significance of this new folk tradition highlights its performance perspective. Taiko, performed before an audience, carries cultural, his- torical, and social messages from Japanese Americans to their own com- munity and also to the larger society. Sansei performers began to perform taiko because they found it “calls attention to and involves self-conscious manipulation of the formal features of the communicative system.”2 Taiko mediates the inner struggles and dilemmas of individual sansei performers through the reflexivity of its performance. Presented in public, the emerging American taiko tradition has also matured into Copyright © 2001 Hideyo Konagaya. All rights reserved. This work may be used, with this notice included, for noncommercial purposes. No copies of this work may be distributed, electronically or otherwise, in whole or in part, without per- mission from the author. 105 106 HIDEYO KONAGAYA a cultural performance, and functions as a means for the Japanese American community to claim higher esteem in multicultural American society.