Development and Support of Taiko in the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BCA Voices - August 27, 1981 by Rev

The Newsletter of Ekoji Buddhist Temple alavinka Fairfax Station, Virginia - Established 1981 Vol. XXXIII, No. 7 July 2014 BCA Voices - August 27, 1981 By Rev. Kenryu Tsuji This month, we are changing the column up a little heat, it gave shelter to countless insects, even giving and including a poem by Rev. Kenryu Tsuji, former a part of itself to the hungry bugs. Ekoji Resident Minister and former Bishop of the Bud- And now, it is that time of the year. dhist Churches of America. According to Ekoji’s for- mer librarian, Valorie Lee, this piece “is one of Rev. But before it falls from its branch, it prepares for the Tsuji’s writings that may be the closest he ventured in future, for next spring, a fresh green leaf will shoot the direction of poetry. It originally appeared in the out from the same branch. In its twilight hours it Kalavinka and then was included in The Heart of the displayed to the world, without pride, without self- Buddha Dharma. Not titled in the Kalavinka, but re- consciousness, its ultimate beauty. quiring one for the book, I used the date of the Kala- vinka issue in which it appeared.” Does the human spirit grow more beautiful with each passing day? Or does it become more engrossed August 27, 1981 in its mortality by creating stronger hands of self- attachment? It is that time of the year. Is my life reflecting a deeper beauty as I grow older? A single red maple leaf performs a graceful ballet What karmic influences will I leave for the good of in the cool autumn breeze before it finally joins the the world? other leaves on the ground. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1990

National Endowment For The Arts Annual Report National Endowment For The Arts 1990 Annual Report National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1990. Respectfully, Jc Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. April 1991 CONTENTS Chairman’s Statement ............................................................5 The Agency and its Functions .............................................29 . The National Council on the Arts ........................................30 Programs Dance ........................................................................................ 32 Design Arts .............................................................................. 53 Expansion Arts .....................................................................66 ... Folk Arts .................................................................................. 92 Inter-Arts ..................................................................................103. Literature ..............................................................................121 .... Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ..................................137 .. Museum ................................................................................155 .... Music ....................................................................................186 .... 236 ~O~eera-Musicalater ................................................................................ -

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This Page Intentionally Left Blank Shadows in the Field

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This page intentionally left blank Shadows in the Field New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology Second Edition Edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley 1 2008 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright # 2008 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shadows in the field : new perspectives for fieldwork in ethnomusicology / edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley. — 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-532495-2; 978-0-19-532496-9 (pbk.) 1. Ethnomusicology—Fieldwork. I. Barz, Gregory F., 1960– II. Cooley, Timothy J., 1962– ML3799.S5 2008 780.89—dc22 2008023530 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper bruno nettl Foreword Fieldworker’s Progress Shadows in the Field, in its first edition a varied collection of interesting, insightful essays about fieldwork, has now been significantly expanded and revised, becoming the first comprehensive book about fieldwork in ethnomusicology. -

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice: Community formation outside original context A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Craig E. Rodrigue Jr. Dr. Erin E. Stiles/Thesis Advisor May, 2017 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by CRAIG E. RODRIGUE JR. Entitled American Shinto Community Of Practice: Community Formation Outside Original Context be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Erin E. Stiles, Advisor Jenanne K. Ferguson, Committee Member Meredith Oda, Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2017 i Abstract Shinto is a native Japanese religion with a history that goes back thousands of years. Because of its close ties to Japanese culture, and Shinto’s strong emphasis on place in its practice, it does not seem to be the kind of religion that would migrate to other areas of the world and convert new practitioners. However, not only are there examples of Shinto being practiced outside of Japan, the people doing the practice are not always of Japanese heritage. The Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America is one of the only fully functional Shinto shrines in the United States and is run by the first non-Japanese Shinto priest. This thesis looks at the community of practice that surrounds this American shrine and examines how membership is negotiated through action. There are three main practices that form the larger community: language use, rituals, and Aikido. Through participation in these activities members engage with an American Shinto community of practice. -

Teachers' Notes:Taiko Drums & Flutes of Japan Japanese Musical

Teachers’ Notes: Taiko Drums & Flutes of Japan Japanese Musical Instruments Shakuhachi This Japanese flute with only five finger holes is made of the root end of a heavy variety of bamboo. From around 1600 through to the late 1800’s the shakuhachi was used exclusively as a tool for Zen meditation. Since the Meiji restoration (1868), the shakuhachi has performed in chamber music combinations with koto (zither), shamisen (lute) and voice. In the 20 th century, shakuhachi has performed in many types of ensembles in combination with non-Japanese instruments. It’s characteristic haunting sounds, evocative of nature, are frequently featured in film music. Koto (in Anne’s Japanese Music Show, not Taiko performance) Like the shakuhachi , the koto (a 13 stringed zither) ORIGINATED IN China and a uniquely Japanese musical vocabulary and performance aesthetic has gradually developed over its 1200 years in Japan. Used both in ensemble and as a solo virtuosic instrument, this harp-like instrument has a great tuning flexibility and has therefore adapted well to cross cultural music genres. Taiko These drums come in many sizes and have been traditionally associated with religious rites at Shinto shrines as well as village festivals. In the last 30 years, Taiko drumming groups have flourished in Japan and have become poplar worldwide for their fast pounding rhythms. Sasara A string of small wooden slats, which make a large rattling sound when played with a “whipping” action. Kane A small hand held gong. Chappa A small pair of cymbals Sasara Kane Bookings -

Asian Americans and Creative Music Legacies

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Asian Americans and Creative Music Legacies Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7hf4q6w5 Journal Critical Studies in Improvisation / Études critiques en improvisation, 1(3) Author Dessen, MJ Publication Date 2006 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Critical Studies in Improvisation / Études critiques en improvisation, Vol 1, No 3 (2006) Asian Americans and Creative Music Legacies Michael Dessen, Hampshire College Introduction Throughout the twentieth century, African American improvisers not only created innovative musical practices, but also—often despite staggering odds—helped shape the ideas and the economic infrastructures which surrounded their own artistic productions. Recent studies such as Eric Porter’s What is this Thing Called Jazz? have begun to document these musicians’ struggles to articulate their aesthetic philosophies, to support and educate their communities, to create new audiences, and to establish economic and cultural capital. Through studying these histories, we see new dimensions of these artists’ creativity and resourcefulness, and we also gain a richer understanding of the music. Both their larger goals and the forces working against them—most notably the powerful legacies of systemic racism—all come into sharper focus. As Porter’s book makes clear, African American musicians were active on these multiple fronts throughout the entire century. Yet during the 1960s, bolstered by the Civil Rights -

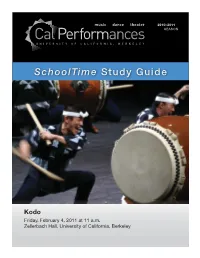

Kodo Study Guide 1011.Indd

2010–2011 SEASON SchoolTime Study Guide Kodo Friday, February 4, 2011 at 11 a.m. Zellerbach Hall, University of California, Berkeley Welcome to SchoolTime On Friday, February 4 at 11am, your class will att end a SchoolTime performance of Kodo (Taiko drumming) at Cal Performances’ Zellerbach Hall. In Japan, “Kodo” meana either “hearbeat” or “children of the drum.” These versati le performers play a variety of instruments – some massive in size, some extraordinarily delicate that mesmerize audiences. Performing in unison, they wield their sti cks like expert swordsmen, evoking thrilling images of ancient and modern Japan. Witnessing a performance by Kodo inspires primal feelings, like plugging into the pulse of the universe itself. Using This Study Guide You can use this study guide to engage your students and enrich their Cal Performances fi eld trip. Before att ending the performance, we encourage you to: • Copy the Student Resource Sheet on pages 2 & 3 for your students to use before the show. • Discuss the informati on on pages 4-5 About the Performance & Arti sts. • Read About the Art Form on page 6, and About Japan on page 11 with your students. • Engage your class in two or more acti viti es on pages 13-14. • Refl ect by asking students the guiding questi ons, found on pages 2,4,6 & 11. • Immerse students further into the subject matt er and art form by using the Resource and Glossary secti ons on pages 15 & 16. At the performance: Your class can acti vely parti cipate during the performance by: • Listening to Kodo’s powerful drum rhythms and expressive music • Observing how the performers’ movements and gestures enhance the performance • Thinking about how you are experiencing a bit of Japanese culture and history by att ending a live performance of taiko drumming • Marveling at the skill of the performers • Refl ecti ng on the sounds, sights, and performance skills you experience at the theater. -

In North America

Shifting Identities of Taiko Music in North America }ibshitaka Zerada National Museum of Ethnology Many Japanese communities in North America hold a Bon (or O- bon) festival every summer, when the spirit of the deceased is summoned to the world ofthe living fbr entertainment of dance and music.i At such festivals, one often encounters a group of energetic and smiling perfbrmers playing various types of drums in tightly choreographed movements. The roaring sound of drums resembles `rolling thunder' and the joyous energy emanating from perfbrmers is captivating. The music they play is known as taiko, and approximately 150 groups are actively engaged in performing this music in North America today.2 This paper aims to provide a brief overview of the development of taiko music and to analyze the relationship between taiko music and the construction of identity among Asians in North America. 71aiko is a Japanese term that refers in its broadest sense to drums in general. In order to distinguish them from those of foreign origin, Japanese drums are often referred to as wadaiko, literally meaning `Japanese drum'. Although the roots ofwadaiko music may be traced to the drum and flute ensembles that accompanied Shinto rituals, agricultural rites, and Bon festivals in Japan for centuries, wadaiko has come to mean a new drumming style that developed after World War II out of the music played by such ensembles. North American taiko is based largely on this post-War wadaiko muslc, contrary to lts anclent lmage. Madaiko music is distinguished from previous drumming traditions in Japan by a style of communal playing known as kumidaiko, involving a multiple number of drummers and a set of taiko drums in various shapes and sizes. -

Wadaiko in Japan and the United States: the Intercultural History of a Musical Genre

Wadaiko in Japan and the United States: The Intercultural History of a Musical Genre by Benjamin Jefferson Pachter Bachelors of Music, Duquesne University, 2002 Master of Music, Southern Methodist University, 2004 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2010 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences This dissertation was presented by Benjamin Pachter It was defended on April 8, 2013 and approved by Adriana Helbig Brenda Jordan Andrew Weintraub Deborah Wong Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung ii Copyright © by Benjamin Pachter 2013 iii Wadaiko in Japan and the United States: The Intercultural History of a Musical Genre Benjamin Pachter, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 This dissertation is a musical history of wadaiko, a genre that emerged in the mid-1950s featuring Japanese taiko drums as the main instruments. Through the analysis of compositions and performances by artists in Japan and the United States, I reveal how Japanese musical forms like hōgaku and matsuri-bayashi have been melded with non-Japanese styles such as jazz. I also demonstrate how the art form first appeared as performed by large ensembles, but later developed into a wide variety of other modes of performance that included small ensembles and soloists. Additionally, I discuss the spread of wadaiko from Japan to the United States, examining the effect of interactions between artists in the two countries on the creation of repertoire; in this way, I reveal how a musical genre develops in an intercultural environment. -

Perspectives in North American Taiko Sano and Uyechi, Spring 2004

Music 17Q Perspectives in North American Taiko Sano and Uyechi, Spring 2004 M W: 2:15 – 4:05 p.m., Braun 106 (M), Braun Rehearsal Hall (W) 4 units Course Syllabus Taiko, used here to refer to performance ensemble drumming using the taiko, or Japanese drum, is a relative newcomer to the American music scene. The emergence of the first North American groups coincided with increased activism in the Japanese American community and, to some, is symbolic of Japanese American identity. To others, North American taiko is associated with Japanese American Buddhism, and to others taiko is a performance art rooted in Japan. In this course we will explore the musical, cultural, historical, and political perspectives of taiko in North America through drumming (hands-on experience), readings, class discussions, workshops, and a research project. With taiko as the focal point, we will learn about Japanese music and Japanese American history, and explore relations between performance, cultural expression, community, and identity. COURSE REQUIREMENTS Students must attend all workshops and complete all assignments to receive credit for the course. Reaction Papers (30%) Midterm (20%) Research Project (40%) Attendance/Participation (10%) COURSE FEE $30 to partially cover cost of bachi, bachi bag, concert tickets, workshop fees, gas and parking for drivers. READINGS 1. Course reader available at the Stanford Bookstore. 2. Strangers From a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans. Ronald Takaki. 1989. Penguin Books. GENERAL INFORMATION Instructors Steve Sano Linda Uyechi Office Braun 120 Office Phone 723-1570 Phone 494-1321 494-1321 (8 a.m. – 10 p.m.) Email sano@leland [email protected] 1 COURSE OUTLINE WEEK 1 (March 31) Wednesday Introduction: What is North American Taiko? Reading Terada, Y. -

Copyright by Angela Kristine Ahlgren 2011

Copyright by Angela Kristine Ahlgren 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Angela Kristine Ahlgren certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Drumming Asian America: Performing Race, Gender, and Sexuality in North American Taiko Committee: ______________________________________ Jill Dolan, Co-Supervisor ______________________________________ Charlotte Canning, Co-Supervisor ______________________________________ Joni L. Jones ______________________________________ Deborah Paredez ______________________________________ Deborah Wong Drumming Asian America: Performing Race, Gender, and Sexuality in North American Taiko by Angela Kristine Ahlgren, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Dedication To those who play, teach, and love taiko, Ganbatte! Acknowledgments I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to each person whose insight, labor, and goodwill contributed to this dissertation. To my advisor, Jill Dolan, I offer the deepest thanks for supporting my work with great care, enthusiasm, and wisdom. I am also grateful to my co-advisor Charlotte Canning for her generosity and sense of humor in the face of bureaucratic hurdles. I want to thank each member of my committee, Deborah Paredez, Omi Osun Olomo/Joni L. Jones, and Deborah Wong, for the time they spent reading and responding to my work, and for all their inspiring scholarship, teaching, and mentoring throughout this process. My teachers, colleagues, and friends in the Performance as Public Practice program at the University of Texas have been and continue to be an inspiring community of scholars and artists. -

WISTERIA, CHERRY TREES, and MOUNTAINS: PRESENTING a NEW MODEL for UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST COMMUNITIES in the UNITED STATES by CL

WISTERIA, CHERRY TREES, AND MOUNTAINS: PRESENTING A NEW MODEL FOR UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST COMMUNITIES IN THE UNITED STATES by CLAIRE MILLER SKRILETZ B.A., Drew University, 2002 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Religious Studies 2012 This thesis entitled: Wisteria, Cherry Trees, and Mountains: A New Model for Understanding Buddhist Communities in the United States written by Claire Miller Skriletz has been approved for the Department of Religious Studies _____________________________________________ Dr. Holly Gayley, Committee Chair & Assistant Professor, Religious Studies ______________________________________________ Dr. Greg Johnson, Associate Professor, Religious Studies _______________________________________________ Dr. Deborah Whitehead, Assistant Professor, Religious Studies Date____________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Miller Skriletz, Claire. (M.A., Religious Studies) Wisteria, Cherry Trees, and Mountains: A New Model for Understanding Buddhist Communities in the United States Thesis directed by Assistant Professor Holly Gayley This thesis critiques the existing binary categories applied to American Buddhism, that of ethnic and convert. First, a critique of existing models and the term ethnic is presented. In light of the critique and the shortcomings of existing models, this thesis presents a new model for studying and classifying Buddhist communities in the United States, culturally-informed Buddhisms. Chapter Three of the thesis applies the culturally-informed Buddhisms model to case studies of the websites for the Buddhist Churches of America organization and the Tri-State/Denver Buddhist Temple.