Amphibians of Algeria: New Data on the Occurrence and Natural History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Smet K. 2003. Cheetah in and Around Hoggar National Park in Central Sahara (Algeria)

de Smet K. 2003. Cheetah in and around Hoggar National Park in Central Sahara (Algeria). Cat News 38(Spring):22-4. Keywords: 1DZ/Acinonyx jubatus/cheetah/Hoggar NP/National Park/North Africa/prey/Sahara/status/ territorial behaviour Abstract: According the studies conducted in the late' 80s, in 2000 and in 2003, the cheetah is largely widespread in the Hoggar Mountains (Algeria) and its surroundings. Their numbers have probably risen since 2000. The potential preys of the cheetah are abundant. However, the cheetah is often killed by the Tuaregs despite their protection status. Cheetahs are reported to move on constantly from one valley to another, but have a territorial behaviour. The absence of competitors allows cheetah to hunt its preys without facing their robbery. The situation may be good in the Tassili Mountains too. D'après les études menées à la fin des années 80, en 2000 et en 2003 le guépard est largement répandu dans les montagnes du Hoggar (Algérie) et ses environs. Leur nombre a probablement augmenté depuis 2000. Les proies potentielles du guépard sont abondantes. Cependant, malgré son statut d'espèce protégée, le guépard est souvent tué par les Touaregs. D'après les observations, les guépards se déplacent constamment d'une vallée à l'autre, mais gardent un comportement territorial. L'absence de compétiteurs permet au guépard de chasser ses proies sans avoir à faire face à leur vol. La situation doit également être bonne dans les montagnes du Tassili. Cheetah in and Around Hoggar National Park in Algeria by Koen de Smet* uring the past 80 years we encountered, and even groups up to covered 1,000 km. -

Demandespharmaciensarretau2

REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE WILAYA DE TIZI-OUZOU DIRECTION DE LA SANTE ET DE LA POPULATION LISTE DES DEMANDES DES PHARMACIENS DE LA WILAYA DE TIZI OUZOU ARRETEE AU 28/02/2019 Commune N° Nom Prénom Lieu exact Date demandée la commune d'Ain El Hammam 1 NAIT BELKACEM Dehbia A.E.H arret abi youcef cote CEM amar ait chikh 12/16/2012 2 KACED Belkacem A.E.H Taourirt Menguelet 11/4/2015 3 AIT SI SLIMANE sofiane A.E.H Ain El hammam 8/21/2016 4 IKEROUIENE Dihia A.E.H à coté de l'arrêt des fourgons d'Iferhounene 9/22/2016 5 AHMED ALI Houria A.E.H Ain El hammam 9/27/2016 6 NAIT BELAID Dihia A.E.H Ain El hammam centre 12/6/2016 7 BEN ZERROUK Meriem A.E.H Route d'ait yahia 12/12/2017 8 ALILOUCHE Saida A.E.H taourirt amrane a coté polyclinique 12/18/2017 9 TAMAZIRT Boussad A.E.H ville AEH, à proximité de l'arret d'ait Yahia 1/11/2018 10 OUKACI Lynda A.E.H Village taourirte Amrane 8/14/2018 11 MESSAOUR Mustapha A.E.H Vge agouni nteslent en face du nouveau hopital 2/12/2019 la commune d'Aghribs 1 CHAREF KHODJA Djamila Aghribs Agouni Oucharki 11/11/2014 2 OURZIK Ouarda Aghribs Agouni Oucharki 4/28/2015 3 OUIDIR Nouara Aghribs Agouni Oucharki 8/30/2015 4 GUIZEF Mohammed Aghribs Agouni Oucharki 11/12/2015 5 DJEBRA Louiza Aghribs Agouni Oucharki 2/22/2017 la commune d'Ain Zaouia 1 MAZARI Sofiane Ain Zaouia Ain Zaouia 2/4/2016 2 TAKILT Hassina Ain Zaouia Ain Zaouia 5/2/2018 la commune d'Ait Aissa Mimoun 1 DEIFOUS BENASSIL Yamina Ait Aissa Mimoun Lekhali (daloute) 12/13/2016 2 SELLAM Yamna Ait Aissa Mimoun village akaoudj 3/2/2017 3 GHAROUT -

Dépôt Du Dossier D'inscription Du 1Oto1tzo21 Au 13T01t2021

-- -----.:- ,., Dépôt du dossier d'inscription du 1OtO1tZO21 au 13t01t2021 ':t: , iarii",;ii ,= , | (r:r-l Liste des étudiants Sciences de Gestion t: r'i.i..l[ ] , /'^Q) , Nb ,'.sù^/ Nom Prénoms Date Nais. Lieu de nal\$qe ,,/.rü,/ 1, ABBOU _-/)tilv / WALID 27 lO7 l7se8 TIGZIRT 2 ABDERRAHIM ".colyy FAHIMA 23/04/Lss8 BOGHNI 3 ABDERRAHMANI AISSA 12/0s/1,ees AIN EL HAMMAM 4 ABDERRAHMANI MADJID 02/10/2OOO AIN EL HAMMAM 5 ABELLACH E KOUCEILA 04/07 /20oo AIN EL HAMMAM 6 ADDAR KATIA 09/o8/2000 OUAGUENOUN 7 ADJEMOUT LENA 24/02/2OOt AZAZGA 8 AFIR ADEL 27 /07 /1997 DRAA BEN KHEDDA 9 AFLOU AMINA oe/03/tsse AZEFFOUNE 10 AGGAR KAHINA 26/0sltgee ltzl ouzou 11 AGGOUN LILIA 2s/02/1997 AZAZGA 12 AGUENACHE KAHINA 06/os/]-ses AZAZGA 13 AGUENI BILAL 1.6/Ot/1996 TIZIOUZOU 1,4 AHMIM AKLI 78/01/1997 Ain el hammam 15 AICHE MAHDI 23/t0/7s98 TIZI OUZOU 1,6 AID SAMI 7s/02/1998 AZAZGA 17 AIT ADDA MELISSA 1.3/Osl7ee7 AIN EL HAMMAM 18 AIT AIDER MASSINISSA 20/04/79s7 FREHA 19 AIT BOUDJEMA YASMINE 24/11/2000 AZAZGA 20 AIT GHERBI D]AMAL 26/01,/]-eee TIZI-OUZOU 2t AIT GUENISSAID Mohamed-amine Ls/07 /tsss AZAZ3A 22 AIT KHALDOUN KATHIA 27 /Os/1e98 TIZI-OUZOU 23 AIT OUARAB YAMINA 26/0s/2OOO Trztouzou 24 AIT YAHIATENE YACINE 30/12/2000 OUADHIA 25 AIT YAHIATENE YOUCEF t7 /01/2000 BOGHNI 26 AKLI KENZA 17 /1.1,/1,ee4 BOUZZEGUEN 27 AKLI NASRINE 30/08/tee8 OUADHIAS la AKLI OUISSEM Lsh2/19ss BOGHNI 29 AKTOUF ABDELLAH 09/08/1e96 DRAA BEN KHEDDA 30 ALILOUCHE ANIS 29/03/7e98 Ttztouzou 31 ALIOUANE HAKIMA Ls/07 /tses TIZI-GHENIFF 32 ALLALA SULTANA 20/12/1.s99 AIN EL HAMMAM 33 ALLAOUA -

Cytogenetic and Genetic Evidence of Male Sexual Inversion by Heat Treatment in the Newt Pleurodeles Poireti

CHROMOSOMA Chromosoma (Bet1) (1984) 90:261-264 Springer-Verlag 1984 Cytogenetic and genetic evidence of male sexual inversion by heat treatment in the newt Pleurodeles poireti C. Dournon 1, F. Guillet 1, D. Boucher 2, and J.C. Lacroix 2 1 Laboratoire de Biologic Animale; 2Laboratoire de G6n~tique du D~veloppement, Universit~ P. et M. Curie, 9 quai St Bernard 75230 Paris Cedex 05, France Abstract. Larvae of Pleurodeles poireti were maintained the lengthy reproductive cycle of the amphibians. It should during their development at a high temperature (31 ~ C). be interesting therefore to identify the genotypic sex of an In several species of amphibians, such a treatment is known experimental animal by cytogenetic or other genetic criteria, to change the sex ratio through the inversion of genotypic i.e. through sex chromosomes or sex-linked characters re- females into phenotypic males. Pleurodeles poireti is an ex- spectively. ception. It is the first reported amphibian in which heat In a geographical race of P. poireti, the sex chromo- induces an inversion of genotypic males into functional phe- somes can be distinguished in preparations of lampbrush notypic females. The sexual genotype of standard and ex- chromosomes of the oocytes (Lacroix 1970). Moreover, perimental phenotypic females was determined through he- Ferrier et al. (1980, 1983), have shown that in P. waltlii terochromosomes in lampbrush stage. In the present study, the enzyme peptidase I shows a sex-linked polymorphism. we have utilised another technique for identification of sex- The effects of heat treatment on sexual differentiation ual genotype, applicable to both phenotypic males and fe- of larvae of P. -

Quaternary Glaciation in the Mediterranean Mountains the Geological Society of London Books Editorial Committee

Quaternary Glaciation in the Mediterranean Mountains The Geological Society of London Books Editorial Committee Chief Editor Rick Law (USA) Society Books Editors Jim Griffiths (UK) Dave Hodgson (UK) Phil Leat (UK) Nick Richardson (UK) Daniela Schmidt (UK) Randell Stephenson (UK) Rob Strachan (UK) Mark Whiteman (UK) Society Books Advisors Ghulam Bhat (India) Marie-Franc¸oise Brunet (France) Anne-Christine Da Silva (Belgium) Jasper Knight (South Africa) Mario Parise (Italy) Satish-Kumar (Japan) Virginia Toy (New Zealand) Marco Vecoli (Saudi Arabia) Geological Society books refereeing procedures The Society makes every effort to ensure that the scientific and production quality of its books matches that of its journals. Since 1997, all book proposals have been refereed by specialist reviewers as well as by the Society’s Books Editorial Committee. If the referees identify weaknesses in the proposal, these must be addressed before the proposal is accepted. Once the book is accepted, the Society Book Editors ensure that the volume editors follow strict guidelines on refereeing and quality control. We insist that individual papers can only be accepted after satisfactory review by two independent referees. The questions on the review forms are similar to those for Journal of the Geological Society. The referees’ forms and comments must be available to the Society’s Book Editors on request. Although many of the books result from meetings, the editors are expected to commission papers that were not presented at the meeting to ensure that the book provides a balanced coverage of the subject. Being accepted for presentation at the meeting does not guarantee inclusion in the book. -

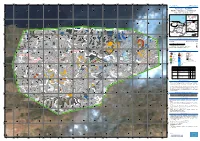

Delineation - Overview Map 01

580000 590000 600000 610000 620000 630000 640000 650000 660000 670000 680000 3°50'0"E 3°55'0"E 4°0'0"E 4°5'0"E 4°10'0"E 4°15'0"E 4°20'0"E 4°25'0"E 4°30'0"E 4°35'0"E 4°40'0"E 4°45'0"E 4°50'0"E 4°55'0"E 5°0'0"E GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSR533 Int. Charter Act. ID: N/A Product N.: 01TIZIOUZOU, v2 N " 0 ' 0 ° 7 Tizi Ouzou - ALGERIA 3 N " 0 ' 0 Wildfire - Situation as of 12/08/2021 ° 7 3 Delineation - Overview map 01 Mediterran ean 0 0 0 0 Sea 0 0 0 0 9 9 0 0 4 4 Portugal Spain Mediterran ean Sea Italy N " NORTH 0 ^ ' ATLANTIC 5 Boum erdès OCEAN Algiers 5 ° 01 SkikTudnaisia 6 (! 3 Tizi Tizi MJoijreoclco N Béjaïa " Ouzou 0 ' 02 5 Ouzou 5 ° 6 Libya 3 Algeria Constantine Mauritania Azeffou n Mila ! Beni Bouira Ksila ! Bordj Bou Sétif Mali Niger L I ɣ Oum el e O T z a Arréridj ḥ u e i e ṣ d r d a a r Bouaghi 0 Iflissen 0 0 Afir Azzefoun 0 0 0 0 0 Msila 8 8 Batna 40 0 Mizrana Tigzirt Ait-Chaffaa 0 4 4 km N Djelfa " 0 ' 0 Khenchela 5 ° 6 3 N " d ue 0 t ' O e k ي ي 0 a S د ب 5 ا و ° Carto g rap hic In fo rmatio n أ 6 3 Beni K'Sila Aghrib Full color A1, 200 dpi resolution Akerrou 1:160000 Boudjima Toudja Zekri Timizart 0 2.5 5 10 Bejaia km Taourga Makouda B M a Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 31N map coordinate system r a r a Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system 0 h 0 0 b g 0 ± e 0 g o e 0 0 a a u 0 N 7 e r i d Azazga 7 ag r u " 0 r 0 r b 0 a a o e To udja ' 4 4 B i B a Ait a ! 5 id Freha 4 S Z ! ° Sidi Naamane au e Aissa 6 e 3 d' n e d Freha Leg en d N a Mimoun " am Ouaguenoun 0 ' n a Crisis Inform ation Placenam es Transportation 5 -

Journal Officiel De La Republique Algerienne Na

19 Dhou El Kaada 1434 JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE N° 47 25 septembre 2013 15 Ressort territorial de la conservation Wilaya Designation de la conservation Daira Commune SAIDA Saida Saida Ain El Hadjar Ain El Hadjar, Sidi Ahmed, Moulay Larbi SAIDA AL HASSASNA Al Hassasna Al Hassasna, Maâmora, Ain Skhouna Ouled Brahim Ouled Brahim, Ain Soltane, Tircine SIDI BOUBEKEUR Sidi Boubekeur Sidi Boubekeur, Sidi Ammar, Hounet, Ouled Khaled Youb Youb, Doui Tabet SKIKDA Skikda Skikda, Filfila, Hammadi Krouma El Hadaiek El Hadaiek, Ain Zouit, Bouchtata EL HARROUCH El Harrouch El Harrouch, Zardezas, Ouled Hebaba, Emdjez Edchich, Salah Bouchaour Ramdane Djamel Ramdane Djamel, Beni Bachir Sidi Mezghiche Sidi Mezghiche, Ain Bouziane, Beni Oulbane SKIKDA Oum Toub Oum Toub Collo Collo, Beni Zid, Cheraia COLLO Zitouna Zitouna, Kenoua Ouled Atia Ouled Atia, Oued Z'hour, Khenag Mayoun Ain Kechera Ain Kechera, Ouldja Boulballout Tamalous Tamalous, Bein El Ouiden, Kerkera Azzaba Azzaba, Djendel Saadi Mohamed, Essebt, Ain Cherchar, AZZABA Elghedir Benazouz Benazouz, El Marsa, Bekkouche Lakhdar SIDI BEL ABBES Sidi Bel Abbès Sidi Bel Abbès SIDI LAHCENE Sidi Lahcène Sidi Lahcène, Sidi Yacoub, Sidi Khaled, Amarnas Tessala Tessala, Ain Thrid, Sehala Thaoura BEN BADIS Ben Badis Ben Badis, Chetouane Belaila, Hassi Zehana, Bedradine El Mokrani Sidi Ali Ben Youb Sidi Ali Ben Youb, Boukhenefis, Tabia SIDI BEL ABBES Sidi Ali Boussidi Sidi Ali Boussidi, Sidi Dahou Dezairs, Ain Kada, Lemtar SFISEF Sfisef Sfisef, Ain Adden, Boudjebaâ El Bordj, M'cid Mostefa Ben Brahim Mostefa Ben Brahim, Zerrouala, Belarbi, Tilmouni Ain El Berd Ain El Berd, Makedra, Sidi Hamadouch, Sidi Brahim Tenira Tenira, Benachiba Chelia, Oued Sefioune, Hassi Daho TELAGH Telagh Telagh, Mezaourou, Dhaya, Teghalimet Moulay Slissen Moulay Slissen, El Hacaiba, Ain Tindamine Merine Merine, Oued Taourira,Tafessour, Taoudmout Ras El Ma Ras El Ma, Oued Sebaâ, Redjem Demouche Marhoum Marhoum, Sidi Chaib, Bir El H'mam. -

Short Note Development and Characterization of Twelve New

*Manuscript Click here to download Manuscript: Isolation and characterization of microsatellite loci for Pleurodeles waltl_final_rev.docx 1 Short Note 2 Development and characterization of twelve new polymorphic microsatellite loci in 3 the Iberian Ribbed newt, Pleurodeles waltl (Caudata: Salamandridae), with data 4 on cross-amplification in P. nebulosus 5 JORGE GUTIÉRREZ-RODRÍGUEZ1, ELENA G. GONZALEZ1, ÍÑIGO 6 MARTÍNEZ-SOLANO2,3,* 7 1 Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC, c/ José Gutiérrez Abascal, 2, 28006 8 Madrid, Spain; 2 Instituto de Investigación en Recursos Cinegéticos, CSIC-UCLM- 9 JCCM, Ronda de Toledo, s/n, 13005 Ciudad Real, Spain; 3 (present address: Centro de 10 Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos (CIBIO), Rua Padre Armando 11 Quintas, s/n, 4485-661 Vairão, Portugal 12 Number of words: 3017; abstract: 138 13 (*) Corresponding author: 14 I. Martínez-Solano 15 Instituto de Investigación en Recursos Cinegéticos (CSIC-UCLM-JCCM) 16 Ronda de Toledo, s/n 17 13005 Ciudad Real, Spain 18 Phone: +34 926 295 450 ext. 6255 19 Fax: +34 926 295 451 20 Email: [email protected] 21 22 Running title: Microsatellite loci in Pleurodeles waltl 23 1 24 Abstract 25 Twelve novel polymorphic microsatellite loci were isolated and characterized for the 26 Iberian Ribbed Newt, Pleurodeles waltl (Caudata, Salamandridae). The distribution of 27 this newt ranges from central and southern Iberia to northwestern Morocco. 28 Polymorphism of these novel loci was tested in 40 individuals from two Iberian 29 populations and compared with previously published markers. The number of alleles 30 per locus ranged from two to eight. Observed and expected heterozygosity ranged from 31 0.13 to 0.57 and from 0.21 to 0.64, respectively. -

DE L'agence BASSIN DES CÔTIERS CONSTANTINOIS

cahiersLes DE l’AGENCE Cahier numéro 4, Septembre 2000 BASSIN DES CÔTIERS CONSTANTINOIS 1 2 BASSIN DES CÔTIERS CONSTANTINOIS PRESENTATION DU BASSIN Potentialités en eau de surface. Les ressources potentielles de chacun des sous bassins Le bassin hydrographique "Côtiers Constantinois" est situé sont les suivantes : dans le littoral Nord de l'Est Algérien, limité au Nord par la Méditerranée, à l'Est par la frontière tunisienne, à l'Ouest Bassins Ressources potentielles par le bassin"Algérois - Hodna - Soummam" et au Sud par versants superficielles (P.N.E)* (hm3/an) les bassins : "Kebir Rhumel", "Seybouse", "Medjerda ". Côtiers Ouest 574,55 Il couvre une superficie totale de 11.509 km2. Côtiers Centre 324,16 Le bassin s'étend sur dix (10) wilayas et cent trente et une Côtiers Est 393,25 (131) communes regroupant une population de un million Total 1291,96 huit cent soixante quatre mille cent quatre vingt et un (1.864.181) habitants selon le recensement de 1998. P.N.E : Plan National de l'Eau L'agglomération de Skikda avec 143.119 habitants est la principale ville du bassin des Côtiers Constantinois. Potentialités en eau souterraine : Les nappes côtières (Jijel, Guerbez, Bouteldja) et la Agglomérations Wilaya Population vallée de Safsaf recèlent d'importantes ressources sou- Principales Recens Recens terraines : 1987 1998 Bassins Potentialité des nappes SKIKDA 21 121495 143119 versants souterraines (hm3/an) JIJEL 18 62793 106003 Selon (P.N.E) Selon (A.N.R.H) TAHER 18 22990 51219 Côtiers Ouest 13,4 AZZABA 21 22120 29372 Côtiers Centre 32,5 174 EL HARROUCH 21 19181 28193 Côtiers Est 57,8 EL KALA 36 16253 21294 Total 103,7 174 La pluviométrie varie de 650 mm, à l'amont du bassin Côtiers, Pour des raisons pratiques chaque bassin hydrogra- à 1800 mm sur les monts de Collo - Jijel, exposés aux vents phique sera traité séparément. -

REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY of AFRICA. Uganda Certificate of Education

REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AFRICA. Uganda Certificate of Education. GEOGRAPHY Code: 273/2, Paper 2 2 hours 30 minutes PART I : THE REST OF AFRICA. INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES: This paper consists of two sections: Part I Rest of Africa. Answer two questions from part I @ question carry 25marks. Any additional question (s) answered will not be marked. Four questions are set and a candidate is required to answer only two questions. This region covers 50% of paper 273/2. 1) Download and print out a hard copy then copy this notes in a fresh book for Rest of Africa paper2. 2) If You need a copy of this work organized by the teacher for Rest of Africa. Call 0775 534057 for a book of Africa and it will be delivered. Emihen – Utec 1 SIZE, SHAPE AND POSITION. POSITION OF AFRICA. Africa is one of the largest continents of the world. It’s the second to the largest landmass combined of Eurasia i.e. Europe and Asia continents. LOCATION: Africa lies between latitudes 37.51’N just West of Cape Blanc in Tunisia to Cape Aghulhas at Latitude 34.51’S a distance of 8,000kms. Africa also lies between Cape Ras Hagun 51.50’E and Cape Verde 17.32’W. SIZE: Africa covers land area of about 30,300,300km2. THE SHAPE: Africa’s shape is unbalanced; with her northern part being bulky and wide, while the southern part being thinner and narrower in appearance. Emihen-Utec 2 The Latitude EQUATOR divides the continent into TWO HALVES, there being approximately; 3800kms between the Cape Agulhas in the south and Equator while between Tunisia and Equator in the North is 4,100kms. -

20000 630000 640000 650000 660000 670000 680000

580000 590000 600000 610000 620000 630000 640000 650000 660000 670000 680000 0 3°50'0"E 3°55'0"E 4°0'0"E 4°5'0"E 4°10'0"E 4°15'0"E 4°20'0"E 4°25'0"E 4°30'0"E 4°35'0"E 4°40'0"E 4°45'0"E 4°50'0"E 4°55'0"E 5°0'0"E 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSR533 1 1 4 4 Int. Charter Act. ID: N/A Product N.: 01TIZIOUZOU, v1 N " 0 Tizi Ouzou - ALGERIA ' 0 ° 7 3 N W ildfire - Situation as of 11/08/2021 " 0 ' 0 ° 7 3 First Estimate Product Mediterran ean Sea 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Balear ic 9 9 Portugal Sea Tyrrhen ian Sea 0 0 Spain Medi terran ean Sea Italy 4 4 Algiers ^ Albo ran Sea NORTH ATLA NTIC Tunis ia Boum erdès OCE AN N Gu lf o f Ga bè s " Sk ik da 0 01 ' ! 5 Tizi ( Morocc o 5 Jijel ° Tizi 6 Ouzou Béjaïa 3 02 N Ouzou " Algeria 0 Libya ' 5 5 ° 6 Constantine 3 Mila Azeffoun Bouira Mauritania ! Beni Sétif Bordj Bou Mali Ksila Niger ! Arréridj Oum el L I e ɣ O T Bouaghi z ḥ a u e i ṣ d e r d a a r 0 Iflissen 0 0 Azzefoun 0 Afir Msila 40 0 0 Batna 0 0 km 8 8 Djelfa 0 Mizrana Ait-Chaffaa 0 4 4 N Khenchela Tigzirt " 0 ' 0 5 ° 6 3 N " 0 ' Carto g rap hic In fo rmatio n 0 5 ° 6 3 و أ ا Beni K'Sila د Full color A1, 200 dpi resolution ب ي 1:160000 ي t e k Aghrib a S Akerrou d e Boudjima Toudja u O 0 3.25 6.5 13 Zekri Timizart km Makouda Bejaia Taourga Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 31N map coordinate system B M a Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system r a r ± a 0 Sidi Naamane h 0 0 e b g 0 0 g o e 0 0 a a 0 r i u N 7 e r u d Azazga 7 ag a Ait " 0 r 0 r o b 0 a e Toudja ' 4 B a 4 B i Aissa a ! 5 id Z Freha 4 Leg en d S ! ° au e Mimoun 6 -

Zootaxa, Caudata, Pleurodeles

Zootaxa 488: 1–24 (2004) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 488 Copyright © 2004 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Taxonomic revision of Algero-Tunisian Pleurodeles (Caudata: Salamandridae) using molecular and morphological data. Revalidation of the taxon Pleurodeles nebulosus (Guichenot, 1850) SALVADOR CARRANZA1* & EDWARD WADE2 1. Department of Zoology, The Natural History Museum, London, SW7 5BD ([email protected]) * Present address: Departament de Biologia Animal, Universitat de Barcelona, Av. Diagonal 645, E-08028 Barcelona, Spain ([email protected]) 2. Middlesex University, Cat Hill, Barnet, Hertfordshire, EN4 8HT ([email protected]) Abstract The taxonomic status of Algero-Tunisian Pleurodeles was reanalysed in the light of new molecular and morphological evidence. Mitochondrial DNA sequences (396 bp of the cytochrome b and 369 of the 12S rRNA) and the results of the morphometric analysis, indicate that Algero-Tunisian P. poireti consists of two genetically and morphologically distinct forms. One restricted to the Edough Peninsula, and another one covering all the rest of its distribution in Algeria and Tunisia. The name P. p oire ti (Gervais, 1835) is restricted to the population of the Edough Peninsula, while P. nebulous (Guichenot, 1850) correctly applies to all other populations in the distribution. P. po ire ti originated approximately 4.2 Myr ago, probably as a result of the Edough Peninsula being a Pliocene fossil island, allowing both forms of Algero-Tunisian Pleurodeles to diverge both genetically and mor- phologically. Key words: Pleurodeles, Algeria, taxonomy, mitochondrial DNA, 12S rRNA, cytochrome b, mor- phology, Pliocene fossil island Introduction The genus Pleurodeles currently consists of two species.