The Border” with New Visualization Technologies by Ellen Currin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Biopolitics and Geopolitics of Border Enforcement in Melilla

The biopolitics and geopolitics of border enforcement in Melilla By: Corey Johnson and Reece Johnson Johnson, C., & Jones, R. (2018). The biopolitics and geopolitics of border enforcement in Melilla. Territory, Politics, Governance 6(1), 61-80. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2016.1236746 This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Territory, Politics, Governance on 06 October 2016, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/21622671.2016.1236746. ***© 2016 Regional Studies Association. Reprinted with permission. No further reproduction is authorized without written permission from Taylor & Francis. This version of the document is not the version of record. Figures and/or pictures may be missing from this format of the document. *** Abstract: This article uses the multiple and contradictory realities of Melilla, a pene-enclave and -exclave of Spain in North Africa, to draw out the contemporary practice of Spanish, European Union, and Moroccan immigration enforcement policies. The city is many things at once: a piece of Europe in North Africa and a symbol of Spain’s colonial history; an example of the contemporary narrative of a cosmopolitan and multicultural Europe; a place where extraterritorial and intraterritorial dynamics demonstrate territory’s continuing allure despite the security challenges and the lack of economic or strategic value; a metaphorical island of contrasting geopolitical and biopolitical practices; and a place of regional flows and cross-border cooperation between Spain, the EU, and Morocco. It is a border where the immunitary logic of sovereign territorial spaces is exposed through the biopolitical practices of the state to ‘protect’ the community from outsiders. -

Hoffman Park Hoffman Park Birds

About Hoffman Park Hoffman Park Birds This 354-acre park is comprised of hardwood Location: Hoffman Park is located in Union A host of different bird species can be found in Township, west of Clinton and just south of the forests and fields, but Hoffman Park is Hoffman forest, grasslands, and many ponds of various sizes. The ponds were created in the 1940s by Interstate 78. The main parking area is at 26 probably best known among bird watchers for Albert and Joyce Hoffman for erosion Baptist Church Road, Hampton 08827. The endangered and threatened species that nest in control, crop irrigation, and cattle gate is open from 9:00 AM to sunset. A second its grassland habitat. These include Bobolinks, Park management when the park was a working parking lot is located at 751 Mechlin Corner Eastern Meadowlarks, Grasshopper Sparrows, farm. Albert Hoffman was the son of the Road, Hampton 08827. and Savannah Sparrows. Please keep pets on a founder of the Hoffman Beverage Company. leash as these birds nest directly on the ground Trail Map and Guide Directions from the East/Clinton area: and are highly susceptible to disturbance. Albert’s skilled innovations led to improvements in the sanitization, labeling, Take Route 78 west to exit 11. Follow the Eastern Bluebird nesting boxes and Wood and packaging of bottles. He also invented circle around to the left and cross over Route Duck boxes were erected in 2000 as part of a biological filters that extracted impurities 78, following the signs for Pattenburg. Boy Scout Eagle project. The bluebird boxes from concentrated sugar syrups. -

Failure to Record Rights Under NPACA 1949 in the West Riding

NFBA Paper 2, March 2007 Failure to record rights under NPACA 1949 in the West Riding The lack of higher rights of way on the present-day definitive maps in the metropolitan boroughs in West Yorkshire can be directly attributed to manipulation of the recording procedure by West Riding County Council in the 1950s and 60s. It is not that the true status of routes was not known, or that evidence did not exist, or that people did not claim bridleways and RUPPs. There was a deliberate decision by the county council – and colluded in by some of the district councils – to reduce the public maintenance liability by altering the status of bridleways and RUPPs shown on the draft map to footpaths on the provisional map. This is well documented for the West Riding. The relevant files are available in the West Yorkshire Archives HQ at Wakefield, but the following extracts reveal what happened. 1 Routes that were recorded as cart roads (CRFs and CRBs) on the walking schedule prepared by the district councils were initially recorded as RUPPs on the draft map. 2 This was then advertised. At the end of the consultation process, the county council became concerned at the potential maintenance liability of the recorded footpaths and bridleways, and circulated the following memo: . where the width of any public path has been shown . greater than normal, i.e. that any footpath included in the Statement accompanying the Draft Map which is shown therein at a width not exceeding 6 feet, be retained but all footpaths having greater widths than 6 feet should be changed to 4 feet; likewise that all bridleways (normally considered to be 8 feet wide) which are shown of greater width than 10 feet should be reduced to the standard 8 feet. -

Horseback Riding Is Not Offenses, Which May Be Set Forth in the New Jersey Code of Criminal with Disabilities Upon Advance Notice of Need

1. Hunterdon County SUMMARY OF RULES AND REGULATIONS Arboretum* County Reference Map 2. Charlestown Reserve* The rules and regulations governing use of facilities or properties administered by the Horseback Hunterdon County Division of Parks and Recreation are promulgated in accordance 3. Clover Hill Park with provisions of the N.J. Statutes Title 40:32-7.12, which reads as follows: With the exception of park "The Board of Chosen Freeholders may by resolution make, alter, amend, and properties with reservable facilities, 4. Cold Brook Reserve repeal rules and regulations for the supervision, regulation and control of all all properties are “carry in / carry 5. Columbia Trail activities carried on, conducted, sponsored, arranged, or provided for in Riding connection with a public golf course or other county recreational, playground, out” and trash/recycling 6. Court Street Park* or public entertainment facility, and for the protection of property, and may prescribe and enforce fines and penalties for the violation of any such rule or receptacles are not provided. 7. Crystal Springs Preserve regulation.” Reference Please plan accordingly and do not 8. Cushetunk Mountain These rules and regulations have been promulgated for the protection of leave any trash/recyclables behind. our patrons and for the facilities and natural resources administered by the Preserve* Hunterdon County Division of Parks and Recreation. 9. Deer Path Park & Round Permits: A fully executed Facility Use Permit, issued by the County of Guide Hunterdon for any activity, shall authorize the activity only insofar as it Mountain Section may be performed in strict accordance with the terms and conditions 10. -

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 12 SEPTEMBER, 1911. 6743 No. 28530. B

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 12 SEPTEMBER, 1911. 6743 DISEASES OF ANIMALS ACTS, 1894 to 1911— continued. The following Areas are now "Infected Areas" for the purposes of the Swine-Fever (Regulation of Movement) Order of 1908—continued. the parishes of Henbury, Bitton, and and such portion of the petty sessional Doynton) in the administrative county of division of Devizes as lies to the north of the Gloucester; and also comprising the city and Great Western Railway line from Pewsey to county borough of Bristol (31 May, 1911). Westbury (15 August, 1911). (3.) An Area in the administrative county (2.) An Area in the administrative county of Gloucester comprising the petty sessional of Wilts comprising the parishes of Durring- division of Berkeley (31 May, 1911). ton and Bulford (14 August, 1911). (4.) An Area in the administrative county Yorkshire (East Biding).—An Area in the of Gloucester comprising the petty sessional administrative county of the East Riding of division of Tewkesbury (including its de- Yorkshire comprising the parish of Iteying- tached parts) and the borough "of Tewkes- ham (20 Attgust, 1911).—See also under bury (4 July, 1911). Yorkshire (North Riding), &c. Herefordshire.—An Area in the administra- tive county of Hereford comprising the Yorkshire (North Riding), &c.—(1.) An parishes of Bridstow, Brampton Abbotts, Area in the administrative county of the TJpton Bishop, L'inton, Aston Ingham, Lea, North Riding of Yorkshire comprising the Weston under Penyard, Hope Mansel, Wai- parish of Seainer and the borough of Scar- ford, Ross Rural, and Ross Urban (10 July, borough f22 June, 1911). 1911). -

Manitoba's Legislative Assembly Is Made up of 57 Persons Known As Members Or Mlas

Manitoba's Legislative Assembly is made up of 57 persons known as Members or MLAs. Each Member represents a certain area of the province known either as an electoral division, constituency or riding. How does someone become a Member of the Legislative Assembly in the first place? Is a candidate chosen by the Premier? or by a political party (for example, the Liberal Party, the New Democratic Party, or the Progressive Conservative Party)? To answer these questions, let 's follow the process of becoming a candidate and getting elected as an A person who wants to be a candidate but has a job can write his or her For more information contact: Office of the Speaker employer to request time off.244 LegislativeAccording Building, 450 Broadway to the act, the employer must Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3C 0V8 (204) 945-3706 or toll free in Manitoba, 1-800-282-8069 grantHow adoes leavesomeone becomeof aabsence [email protected] pay to such an employee, unless the employerMember ofcan the Legislative prove that the leave would seriously harm the employer's operations.MLA.Assembly in the first place? Let 's assume that our candidate-to-be has met all the requirements listed above. He or she may want to run for a particu- lar party and may go after a nomination within it. The party holds an Legislative Assembly of Manitoba election of its own to determine who will be its official representative.How Members are Elected If our candidate is successful, then he orManitoba she has the party's backing Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) Running as an independent The Returning Officer for each electoral division makes Manitoba's Legislative Assembly is made up of 57 Our candidate may not want to represent a particu- the detailed arrangements for holding the election in persons known as Members or MLAs. -

OHV Trail Riding by District

OHV Trail Riding by District Cascade Dense forest is the striking setting for the Telephone Ridge area, located about 8 miles south of Warm Lake. Approximately 20 miles of single track trails and some ATV trails (maximum vehicle width 50 inches) are available. Trails are marked, but not rated. Staging can be done at Shoreline and Warm Lake campgrounds and Vulcan Trailhead. OHV’s are allowed to enter and exit the campgrounds to access the designated trails. Due to the high elevation, the best time to visit this area is often later in the summer due to potential snow cover or drifts. Swimming and boating opportunities are available at Warm Lake. UTV riding is available on FS RD 478 to its terminus at Rice Lake trailhead. From there, single track trails are available. Terrain is a mix of loose dirt and hard pack. Another option that provides stunning views from the ridge is the East Mountain Trail (#099). This designated ATV trail is accessed primarily off FS RD 409 when driven from south to north. Roughly 17 miles in length, this trail has multiple trailheads. For details, contact the Cascade Ranger Station at 208- 382-7400 or use the Cascade Ranger District Motor Vehicle Use Map. Emmett Located north of scenic Sagehen Reservoir, the Sagehen ATV Trail System connects 13 different ATV trails together to create a network of approximately 19 miles of trail opportunities. The trails vary in length from .4 to 3.7 miles in length. In addition, there are two single track trails in the vicinity. The West Mountain Trail (#131) is 5.2 miles in length and Joe’s Creek Trail (#137) is 1.96 miles in length and joins the West Mountain Trail. -

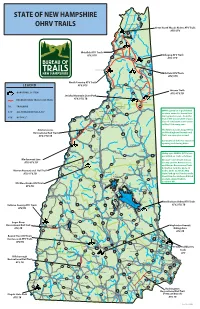

State of New Hampshire Ohrv Trails

STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE Third Connecticut Lake 3 OHRV TRAILS Second Connecticut Lake First Connecticut Lake Great North Woods Riders ATV Trails ATV, UTV 3 Pittsburg Lake Francis 145 Metallak ATV Trails Colebrook ATV, UTV Dixville Notch Umbagog ATV Trails 3 ATV, UTV 26 16 ErrolLake Umbagog N. Stratford 26 Millsfield ATV Trails 16 ATV, UTV North Country ATV Trails LEGEND ATV, UTV Stark 110 Groveton Milan Success Trails OHRV TRAIL SYSTEM 110 ATV, UTV, TB Jericho Mountain State Park ATV, UTV, TB RECREATIONAL TRAIL / LINK TRAIL Lancaster Berlin TB: TRAILBIKE 3 Jefferson 16 302 Gorham 116 OHRV operation is prohibited ATV: ALL TERRAIN VEHICLE, 50” 135 Whitefield on state-owned or leased land 2 115 during mud season - from the UTV: UP TO 62” Littleton end of the snowmobile season 135 Carroll Bethleham (loss of consistent snow cover) Mt. Washington Bretton Woods to May 23rd every year. 93 Twin Mountain Franconia 3 Ammonoosuc The Ammonoosuc, Sugar River, Recreational Rail Trail 302 16 and Rockingham Recreational 10 302 116 Jackson Trails are open year-round. ATV, UTV, TB Woodsville Franconia Crawford Notch Notch Contact local clubs for seasonal opening and closing dates. Bartlett 112 North Haverhill Lincoln North Woodstock Conway Utility style OHRV’s (UTV’s) are 10 112 302 permitted on trails as follows: 118 Conway Waterville Valley Blackmount Line On state-owned trails in Coos 16 ATV, UTV, TB Warren County and the Ammonoosuc 49 Eaton Orford Madison and Warren Recreational Trails in Grafton Counties up to 62 Wentworth Tamworth Warren Recreational Rail Trail 153 inches wide. In Jericho Mtn Campton ATV, UTV, TB State Park up to 65 inches wide. -

Site Development Review Application

Site Development Review Application for Horse Boarding and/ or Riding Academy Alameda County Planning Department 224 West Winton Avenue, Room 111, Hayward, CA 94544 Phone: (510) 670-5400 Fax: (510) 785-8793 Web: http://www.acgov.org/cda/planning 1. Applicant Name: 2. Contact the Planning Department at (510) 670-5410 to make an appointment with a Senior Planner to submit the following materials to the Alameda County Planning Department (Zoning Counter) at 399 Elmhurst Street, Hayward, California. Incomplete applications will not be accepted. Please use the following checklist to ensure the application is complete. Required Completed Boarding Stables/Riding Academy Application Completed Manure Management Worksheet Filing Fee Deposit: $2,000. Make check payable to “Treasurer, County of Alameda.” If this deposit is depleted, the Planning Staff will advise you that additional funds must be deposited to continue the processing of this application. Any remaining unexpended money will be refunded. (Note: $200 of this is a flat fee for the Alameda County Fire Department. The other $1,800 is a Planning Department “fee deposit” toward permit processing. If fee deposit is depleted, applicant must deposit additional funds to continue application processing. Any remaining money will be refunded.) Plans: Show all information as described in item #4 of this application, to the scale indicated. • black line prints of each sheet, folded to 8.5” x 11”: • 13 copies if you are in the East Board of Zoning Adjustments area • 13 copies if you are in the West Board of Zoning Adjustments area, other than Castro Valley • 20 copies if you are in the Castro Valley Canyonlands (for Castro Valley Municipal Advisory Committee and West BZA). -

Municipal Officials Directory 2021

MANITOBA MUNICIPAL RELATIONS Municipal Officials Directory 21 Last updated: September 23, 2021 Email updates: [email protected] MINISTER OF MUNICIPAL RELATIONS Room 317 Legislative Building Winnipeg, Manitoba CANADA R3C 0V8 ,DPSOHDVHGWRSUHVHQWWKHXSGDWHGRQOLQHGRZQORDGDEOH0XQLFLSDO2IILFLDOV'LUHFWRU\7KLV IRUPDWSURYLGHVDOOXVHUVZLWKFRQWLQXDOO\XSGDWHGDFFXUDWHDQGUHOLDEOHLQIRUPDWLRQ$FRS\ FDQEHGRZQORDGHGIURPWKH3URYLQFH¶VZHEVLWHDWWKHIROORZLQJDGGUHVV KWWSZZZJRYPEFDLDFRQWDFWXVSXEVPRGSGI 7KH0XQLFLSDO2IILFLDOV'LUHFWRU\FRQWDLQVFRPSUHKHQVLYHFRQWDFWLQIRUPDWLRQIRUDOORI 0DQLWRED¶VPXQLFLSDOLWLHV,WSURYLGHVQDPHVRIDOOFRXQFLOPHPEHUVDQGFKLHI DGPLQLVWUDWLYHRIILFHUVWKHVFKHGXOHRIUHJXODUFRXQFLOPHHWLQJVDQGSRSXODWLRQV,WDOVR SURYLGHVWKHQDPHVDQGFRQWDFWLQIRUPDWLRQRIPXQLFLSDORUJDQL]DWLRQV0DQLWRED([HFXWLYH &RXQFLO0HPEHUVDQG0HPEHUVRIWKH/HJLVODWLYH$VVHPEO\RIILFLDOVRI0DQLWRED0XQLFLSDO 5HODWLRQVDQGRWKHUNH\SURYLQFLDOGHSDUWPHQWV ,HQFRXUDJH\RXWRFRQWDFWSURYLQFLDORIILFLDOVLI\RXKDYHDQ\TXHVWLRQVRUUHTXLUH LQIRUPDWLRQDERXWSURYLQFLDOSURJUDPVDQGVHUYLFHV ,ORRNIRUZDUGWRZRUNLQJLQSDUWQHUVKLSZLWKDOOPXQLFLSDOFRXQFLOVDQGPXQLFLSDO RUJDQL]DWLRQVDVZHZRUNWRJHWKHUWREXLOGVWURQJYLEUDQWDQGSURVSHURXVFRPPXQLWLHV DFURVV0DQLWRED +RQRXUDEOHDerek Johnson 0LQLVWHU TABLE OF CONTENTS MANITOBA EXECUTIVE COUNCIL IN ORDER OF PRECEDENCE ............................. 2 PROVINCE OF MANITOBA – DEPUTY MINISTERS ..................................................... 5 MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY ............................................................ 7 MUNICIPAL RELATIONS .............................................................................................. -

Finding Your Local Member of Provincial Government

Finding Your Local Member of Provincial Government If you are not sure who your elected provincial/territorial representative (MPP/MNA/MLA) is, please consult the appropriate link below. You may need to know your electoral district/division, constituency or riding in order to search the sites. Alberta: http://streetkey.elections.ab.ca/ - Enter your postal code, street address or electoral division to search for your MLA British Columbia: http://www.leg.bc.ca/mla/3-1-1.htm - Select your constituency, community or enter your postal code to search for your MLA Manitoba: http://www.electionsmanitoba.ca/en/Related_Links/Who_is_My_MLA.html - Enter your street address or City, Town, First Nation or Municipality to search for your MLA New Brunswick: http://www1.gnb.ca/elections/provstreetkey/provskinformation-e.asp - Enter your street name AND select your community to search for your MLA Newfoundland & Labrador: http://www.assembly.nl.ca/members/contact-your-member.htm - Browse for your MNA by district at: http://www.assembly.nl.ca/members/cms/membersdistrict.asp - If you don’t know your district, click here: http://www.elections.gov.nl.ca/elections/findyourdistrict.asp Northwest Territories: http://www.assembly.gov.nt.ca/_live/pages/wpPages/members16thassembly.aspx - Browse the list of MLAs by looking at the constituency names listed - If you do not know your electoral district, consult the map at: http://www.electionsnwt.ca/wp- content/upLoads/2009/09/nwt-large-28apr11.pdf Nova Scotia: http://electionsnovascotia.ns.ca/edf/edf.aspx - Enter your -

Impact on Equestrian Sport Due to Government Restrictions Enforced at 11:59Pm 8 July

IMPACT ON EQUESTRIAN SPORT DUE TO GOVERNMENT RESTRICTIONS ENFORCED AT 11:59PM 8 JULY Date: THURSDAY 9 JULY 2020 Equestrian Victoria, Pony Club Victoria and the HRCAV are committed to ensuring the health and safety of our members and community. We are in constant communication with the Victorian Department for Health and Human Services (DHHS) and Sport and Recreation Victoria (SRV) and take this opportunity to update the equestrian community. Based on advice of the Chief Health Officer, Stage 3 "Stay at Home" restrictions were reinstated across metropolitan Melbourne and Mitchell Shire from 11:59pm on Wednesday 8 July. Read the Statement from the Premier. For six weeks, if you live in the Melbourne Metropolitan region or Mitchell Shire, the Premier has directed that there be only four reasons to leave your home: 1. Shopping for food and essential items. 2. Care and caregiving. 3. Exercise. 4. Work and study –if you can’t do it from home. Otherwise: Stay home. Stay home. Stay home. A Restrictions Map can help you find your location and confirm whether or not the restrictions refer to your area. https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/victorias-restriction-levels-covid-19. Page 1 of 6 Community Sport Firstly, we should all be aware of the restrictions on Community Sport. The following is an excerpt from the DHHS website (https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/sport-and-exercise-metropolitan-melbourne-and-mitchell-shire- covid-19) What activities will be restricted? From 11:59pm, 8 July in metropolitan Melbourne or the Shire of Mitchell the following activities will be restricted: • You can only exercise or undertake sporting activities outside with one other person or household members.