Sports Ankle Injuries Assessment and Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Total HIP Replacement Exercise Program 1. Ankle Pumps 2. Quad

3 sets of 10 reps (30 ea) 2 times a day Total HIP Replacement Exercise Program 5. Heel slides 1. Ankle Pumps Bend knee and pull heel toward buttocks. DO NOT GO Gently point toes up towards your nose and down PAST 90* HIP FLEXION towards the surface. Do both ankles at the same time or alternating feet. Perform slowly. 2. Quad Sets Slowly tighten thigh muscles of legs, pushing knees down into the surface. Hold for 10 count. 6. Short Arc Quads Place a large can or rolled towel (about 8”diameter) under the leg. Straighten knee and leg. Hold straight for 5 count. 3. Gluteal Sets Squeeze the buttocks together as tightly as possible. Hold for a 10 count. 7. Knee extension - Long Arc Quads Slowly straighten operated leg and try to hold it for 5 sec. Bend knee, taking foot under the chair. 4. Abduction and Adduction Slide leg out to the side. Keep kneecap pointing toward ceiling. Gently bring leg back to pillow. May do both legs at the same time. Copywriter VHI Corp 3 sets of 10 reps (30 ea) 2 times a day Total HIP Replacement Exercise Program 8. Standing Stair/Step Training: Heel/Toe Raises: 1. The “good” (non-operated) leg goes Holding on to an immovable surface. UP first. Rise up on toes slowly 2. The “bad” (operated) leg goes for a 5 count. Come back to foot flat and lift DOWN first. toes from floor. 3. The cane stays on the level of the operated leg. Resting positions: To Stretch your hip to neutral position: 1. -

Human Functional Anatomy 213 the Ankle and Foot In

2 HUMAN FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY 213 JOINTS OF THE FOOT THE ANKLE AND FOOT IN LOCOMOTION THE HINDFOOT -(JOINTS OF THE TALUS) THIS WEEKS LAB: Forearm and hand TROCHLEAR The ankle, and distal tibiofibular joints READINGS BODY The leg and sole of foot Subtalar joint (Posterior talocalcaneal) 1. Stern – Core concepts – sections 99, 100 and 101 (plus appendices) HEAD 2. Faiz and Moffat – Anatomy at a Glance – Sections 50 and 51 Talocalcaneonavicular 3. Grants Method:- The bones and sole of foot & Joints of the lower limb & Transverse tarsal joints or any other regional textbook - similar sections IN THIS LECTURE I WILL COVER: Joints related to the talus Ankle Subtalar Talocalcaneonavicular THE MID FOOT Transverse tarsal Other tarsal joints THE FOREFOOT Toe joints METATARSAL AND PHALANGEAL Ligaments of the foot JOINTS (same as in the hand) Arches of the foot Except 1st metatarsal and Hallux Movements of the foot & Compartments of the leg No saddle joint at base is 1st metatarsal The ankle in Locomotion Metatarsal head is bound by deep Ankle limps transverse metatarsal ligament 1. Flexor limp Toes are like fingers 2. Extensor limp Same joints, Lumbricals, Interossei, Extensor expansion Axis of foot (for abduction-adduction) is the 2nd toe. 3 4 JOINTS OF THE FOOT JOINTS OF THE FOOT (2 joints that allow inversion and eversion) DISTAL TIBIOFIBULAR SUBTALAR (Posterior talocalcaneal) JOINT Syndesmosis (fibrous joint like interosseous membrane) Two (or three) talocalcaneal joints Posterior is subtalar Fibres arranged to allow a little movement Anterior (and middle) is part of the talocalcaneonavicular. With a strong interosseus ligament running between them (tarsal sinus) THE TALOCALCANEONAVICULAR JOINT The head of the talus fits into a socket formed from the: The anterior talocalcaneal facets. -

Compression Garments for Leg Lymphoedema

Compression garments for leg lymphoedema You have been fitted with a compression garment to help reduce the lymphoedema in your leg. Compression stockings work by limiting the amount of fluid building up in your leg. They provide firm support, enabling the muscles to pump fluid away more effectively. They provide most pressure at the foot and less at the top of the leg so fluid is pushed out of the limb where it will drain away more easily. How do I wear it? • Wear your garment every day to control the swelling in your leg. • Put your garment on as soon as possible after getting up in the morning. This is because as soon as you stand up and start to move around extra fluid goes into your leg and it begins to swell. • Take the garment off before bedtime unless otherwise instructed by your therapist. We appreciate that in hot weather garments can be uncomfortable, but unfortunately this is when it is important to wear it as the heat can increase the swelling. If you would like to leave off your garment for a special occasion please ask the clinic for advice. What should I look out for? Your garment should feel firm but not uncomfortable: • If you notice the garment is rubbing or cutting in, adjust the garment or remove it and reapply it. • If your garment feels tight during the day, try and think about what may have caused this. If you have been busy, sit down and elevate your leg and rest for at least 30 minutes. -

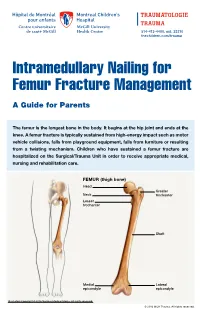

Intramedullary Nailing for Femur Fracture Management a Guide for Parents

514-412-4400, ext. 23310 thechildren.com/trauma Intramedullary Nailing for Femur Fracture Management A Guide for Parents The femur is the longest bone in the body. It begins at the hip joint and ends at the knee. A femur fracture is typically sustained from high-energy impact such as motor vehicle collisions, falls from playground equipment, falls from furniture or resulting from a twisting mechanism. Children who have sustained a femur fracture are hospitalized on the Surgical/Trauma Unit in order to receive appropriate medical, nursing and rehabilitation care. FEMUR (thigh bone) Head Greater Neck trochanter Lesser trochanter Shaft Medial Lateral epicondyle epicondyle Illustration Copyright © 2016 Nucleus Medical Media, All rights reserved. © 2016 MCH Trauma. All rights reserved. FEMUR FRACTURE MANAGEMENT The pediatric Orthopedic Surgeon will assess your child in order to determine the optimal treatment method. Treatment goals include: achieving proper bone realignment, rapid healing, and the return to normal daily activities. The treatment method chosen is primarily based on the child’s age but also taken into consideration are: fracture type, location and other injuries sustained if applicable. Prior to the surgery, your child may be placed in skin traction. This will ensure the bone is in an optimal healing position until it is surgically repaired. Occasionally, traction may be used for a longer period of time. The surgeon will determine if this management is needed based on the specific fracture type and/or location. ELASTIC/FLEXIBLE INTRAMEDULLARY NAILING This surgery is performed by the Orthopedic Surgeon in the Operating Room under general anesthesia. The surgeon will usually make two small incisions near the knee joint in order to insert two flexible titanium rods (intramedullary nails) Flexible through the femur. -

Mcilroy's Ankle Injury Explained

McIlroy’s Ankle Injury Explained By Eva Nugent MISCP The Anterior Talofibular Ligament is big news this week because of world number 1 golf player Rory McIlroy’s injury sustained while having a football “kick about” with friends. McIlroy reports sustaining a “total rupture of his left ATFL and damage to the associated ankle joint capsule”. This unfortunate injury has put his golf season in doubt with the Open Championship starting just next week the 16th of July. But what exactly is the ATFL? And what does the rehabilitation for this injury involve? The Anterior Talofibular Ligament is one of three ligaments that make of the lateral ligament complex of the ankle joint. It originates at the fibular malleoulus of the lateral shin bone (fibula) and runs forward to and attaches to the Talus (ankle bone). The other two ligaments are the Posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL) and the Calcaneofibular ligament (CFL). The function of these ligaments is to provide stability and support to the ankle joint. The ATFL specifically prevents the anterior translation of the shin in relation to the foot/ankle. The ATFL is the most commonly injured ankle ligament and is most vulnerable when the foot is pointing downwards and inwards as the body’s centre of gravity rolls over the ankle (plantarflexed and inverted position). This is commonly described as “going over on your ankle”. It is commonly injured in sports like football or GAA where unpredictable fast turns or cutting movements are involved. This is referred to as an ankle sprain and results in damage to the fibres of the ligament as they are overstretched. -

ANTERIOR KNEE PAIN Home Exercises

ANTERIOR KNEE PAIN Home Exercises Anterior knee pain is pain that occurs at the front and center of the knee. It can be caused by many different problems, including: • Weak or overused muscles • Chondromalacia of the patella (softening and breakdown of the cartilage on the underside of the kneecap) • Inflammations and tendon injury (bursitis, tendonitis) • Loose ligaments with instability of the kneecap • Articular cartilage damage (chondromalacia patella) • Swelling due to fluid buildup in the knee joint • An overload of the extensor mechanism of the knee with or without malalignment of the patella You may feel pain after exercising or when you sit too long. The pain may be a nagging ache or an occasional sharp twinge. Because the pain is around the front of your knee, treatment has traditionally focused on the knee itself and may include taping or bracing the kneecap, or patel- la, and/ or strengthening the thigh muscle—the quadriceps—that helps control your kneecap to improve the contact area between the kneecap and the thigh bone, or femur, beneath it. Howev- er, recent evidence suggests that strengthening your hip and core muscles can also help. The control of your knee from side to side comes from the glutes and core control; that is why those areas are so important in management of anterior knee pain. The exercises below will work on a combination of flexibility and strength of your knee, hip, and core. Although some soreness with exercise is expected, we do not want any sharp pain–pain that gets worse with each rep of an exercise or any increased soreness for more than 24 hours. -

How to Self-Bandage Your Leg(S) and Feet to Reduce Lymphedema (Swelling)

Form: D-8519 How to Self-Bandage Your Leg(s) and Feet to Reduce Lymphedema (Swelling) For patients with lower body lymphedema who have had treatment for cancer, including: • Removal of lymph nodes in the pelvis • Removal of lymph nodes in the groin, or • Radiation to the pelvis Read this resource to learn: • Who needs self-bandaging • Why self-bandaging is important • How to do self-bandaging Disclaimer: This pamphlet is for patients with lymphedema. It is a guide to help patients manage leg swelling with bandages. It is only to be used after the patient has been taught bandaging by a clinician at the Cancer Rehabilitation and Survivorship (CRS) Clinic at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre. Do not self-bandage if you have an infection in your abdomen, leg(s) or feet. Signs of an infection may include: • Swelling in these areas and redness of the skin (this redness can quickly spread) • Pain in your leg(s) or feet • Tenderness and/or warmth in your leg(s) or feet • Fever, chills or feeling unwell If you have an infection or think you have an infection, go to: • Your Family Doctor • Walk-in Clinic • Urgent Care Clinic If no Walk-in clinic is open, go to the closest hospital Emergency Department. 2 What is the lymphatic system? Your lymphatic system removes extra fluid and waste from your body. It plays an important role in how your immune system works. Your lymphatic system is made up of lymph nodes that are linked by lymph vessels. Your lymph nodes are bean-shaped organs that are found all over your body. -

Back of Leg I

Back of Leg I Dr. Garima Sehgal Associate Professor “Only those who risk going too far, can possibly find King George’s Medical University out how far one can go.” UP, Lucknow — T.S. Elliot DISCLAIMER Presentation has been made only for educational purpose Images and data used in the presentation have been taken from various textbooks and other online resources Author of the presentation claims no ownership for this material Learning Objectives By the end of this teaching session on Back of leg – I all the MBBS 1st year students must be able to: • Enumerate the contents of superficial fascia of back of leg • Write a short note on small saphenous vein • Describe cutaneous innervation in the back of leg • Write a short note on sural nerve • Enumerate the boundaries of posterior compartment of leg • Enumerate the fascial compartments in back of leg & their contents • Write a short note on flexor retinaculum of leg- its attachments & structures passing underneath • Describe the origin, insertion nerve supply and actions of superficial muscles of the posterior compartment of leg Introduction- Back of Leg / Calf • Powerful superficial antigravity muscles • (gastrocnemius, soleus) • Muscles are large in size • Inserted into the heel • Raise the heel during walking Superficial fascia of Back of leg • Contains superficial veins- • small saphenous vein with its tributaries • part of course of great saphenous vein • Cutaneous nerves in the back of leg- 1. Saphenous nerve 2. Posterior division of medial cutaneous nerve of thigh 3. Posterior cutaneous -

Active Ankle & Foot Range of Motion Exercises

1501 North Bickett Blvd. Suite E ~ Louisburg, NC 27549 ~ Phone (919) 497-0445 ~ Fax (919) 497-0118 ACTIVE ANKLE & FOOT RANGE OF MOTION EXERCISES Do each exercise _____ times a day. Repeat each exercise ______ times. ANKLE ALPHABET o Moving only your ankle and foot, “write” each letter of the alphabet from A to Z. o Keep your leg straight. o Do not bend your knee or hip. o The letters will start out small and get larger as your ankle motion improves. ANKLE PUMPS o Move your foot up and down as if pushing down or letting up on a gas pedal in a car. ANKLE INVERSION / EVERSION o Move your foot side to side as if mimicking a windshield wiper. o Be sure not to move knee while performing exercise *If you have any questions about these guidelines – or the appropriateness of any other activities – please call Orthopaedic Specialists of North Carolina at (919) 497-0445. 1501 North Bickett Blvd. Suite E ~ Louisburg, NC 27549 ~ Phone (919) 497-0445 ~ Fax (919) 497-0118 ANKLE CIRCLES o Make circles with your foot. o Go clockwise then repeat counter clockwise. TOE CURLS o Moving only your toes, curl and uncurl each digit as far as possible within your pain free range. o Option: Pick-up marbles with toes 1 at a time for 5 minutes. TOE CURLS WITH TOWEL o Bunch up a towel curling your toes TOWEL SLIDES o Moving only your ankle and keeping your heel planted, slide the towel to the inside, then outside. *If you have any questions about these guidelines – or the appropriateness of any other activities – please call Orthopaedic Specialists of North Carolina at (919) 497-0445. -

Getting a Leg up on Land

GETTING A LEG UP in the almost four billion years since life on earth oozed into existence, evolution has generated some marvelous metamorphoses. One of the most spectacular is surely that which produced terrestrial creatures ON bearing limbs, fingers and toes from water-bound fish with fins. Today this group, the tetrapods, encompasses everything from birds and their dinosaur ancestors to lizards, snakes, turtles, frogs and mammals, in- cluding us. Some of these animals have modified or lost their limbs, but their common ancestor had them—two in front and two in back, where LAND fins once flicked instead. Recent fossil discoveries cast The replacement of fins with limbs was a crucial step in this transfor- mation, but it was by no means the only one. As tetrapods ventured onto light on the evolution of shore, they encountered challenges that no vertebrate had ever faced be- four-limbed animals from fish fore—it was not just a matter of developing legs and walking away. Land is a radically different medium from water, and to conquer it, tetrapods BY JENNIFER A. CLACK had to evolve novel ways to breathe, hear, and contend with gravity—the list goes on. Once this extreme makeover reached completion, however, the land was theirs to exploit. Until about 15 years ago, paleontologists understood very little about the sequence of events that made up the transition from fish to tetrapod. We knew that tetrapods had evolved from fish with fleshy fins akin to today’s lungfish and coelacanth, a relation first proposed by American paleontologist Edward D. -

PATIENT INFORMATION Ankle Arthritis

PATIENT INFORMATION Ankle Arthritis The ankle joint The ankle is a very complex joint. It is actually made up of two joints: the true ankle joint and the subtalar ankle joint. The ankle joint consists of three bones held together by cartilage and ligaments. The tibia forms the inside of the true ankle joint. The fibula forms the outside of the true ankle joint. The talus is the underneath part of the true ankle joint. The true ankle joint allows you to move your foot up and down. The subtalar joint consists of two bones, the talus on top and calcaneus on the bottom. The subtalar joint allows you to move your foot from side to side. What is ankle arthritis? Most ankle arthritis is caused by wear and tear which reduces the shiny cartilage that lines the joint causing bone to rub on bone which is painful. (However, there are other forms of arthritis that affect the ankle, for example, rheumatoid arthritis.) Early symptoms of ankle arthritis are pain and perhaps swelling and stiffness, especially after prolonged activity including standing or walking, or after high impact activities, for example running. If you have ankle arthritis, pain, swelling and stiffness can become more frequent as the disease progresses. Eventually you will probably feel pain most of the time, even when you are not active. Healthy ankle joint Arthritic ankle joint Source: Trauma & Orthopaedics Reference No: 5417-3 Issue date: 01/03/2021 Review date: 01/03/2024 Page: 1 of 6 Osteoarthritis is often secondary to damage to the joint, for example as a result of a previous fracture, repeated sprains of the ankle, malalignment of the joint or infection. -

Alexander 2013 Principles-Of-Animal-Locomotion.Pdf

.................................................... Principles of Animal Locomotion Principles of Animal Locomotion ..................................................... R. McNeill Alexander PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD Copyright © 2003 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY All Rights Reserved Second printing, and first paperback printing, 2006 Paperback ISBN-13: 978-0-691-12634-0 Paperback ISBN-10: 0-691-12634-8 The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition of this book as follows Alexander, R. McNeill. Principles of animal locomotion / R. McNeill Alexander. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ). ISBN 0-691-08678-8 (alk. paper) 1. Animal locomotion. I. Title. QP301.A2963 2002 591.47′9—dc21 2002016904 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Galliard and Bulmer Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ pup.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America 1098765432 Contents ............................................................... PREFACE ix Chapter 1. The Best Way to Travel 1 1.1. Fitness 1 1.2. Speed 2 1.3. Acceleration and Maneuverability 2 1.4. Endurance 4 1.5. Economy of Energy 7 1.6. Stability 8 1.7. Compromises 9 1.8. Constraints 9 1.9. Optimization Theory 10 1.10. Gaits 12 Chapter 2. Muscle, the Motor 15 2.1. How Muscles Exert Force 15 2.2. Shortening and Lengthening Muscle 22 2.3. Power Output of Muscles 26 2.4. Pennation Patterns and Moment Arms 28 2.5. Power Consumption 31 2.6. Some Other Types of Muscle 34 Chapter 3.