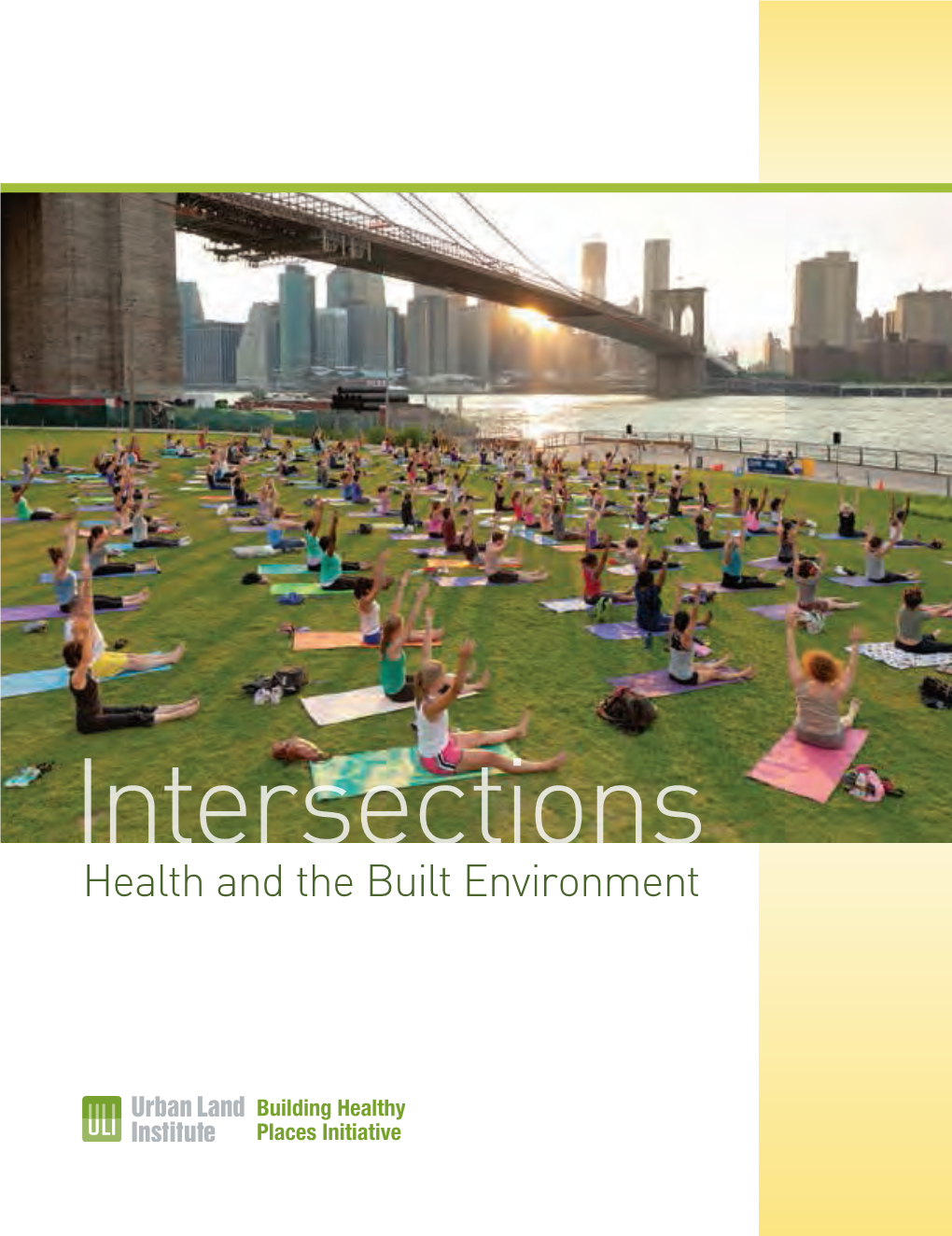

Health and the Built Environment Shows How Change Can Happen—One Community, and One Project, at a Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implementing Sustainability in the Built Environment

Report August 2017 Implementing sustainability in the built environment An analysis of the role and effectiveness of the building and planning system in delivering sustainable cities Trivess Moore, Susie Moloney, Joe Hurley & Andréanne Doyon Implementing sustainability in the built environment: An analysis of the role and effectiveness of the building and planning system in delivering sustainable cities. Trivess Moore, Susie Moloney, Joe Hurley and Andréanne Doyon School of Global, Urban and Social Studies and School of Property, Construction and Project Management, RMIT University. August 2017 Contact: Joe Hurley RMIT University GPO Box 2476 Melbourne Vic 3001 [email protected] Phone : 61 3 9925 9016 Published by: Centre for Urban Research (CUR) RMIT University | City campus Building 15, Level 4 124 La Trobe Street Melbourne VIC 3000 www.cur.org.au @RMIT_CUR facebook.com/rmitcur Layout and design: Chanel Bearder 2 Contents Executive summary 4 1. Introduction 7 1.1 Introduction 7 1.2 Project description, aim and scope 7 1.3 Methods 9 1.4 Project Context: Transitioning to a sustainable built environment future 10 2. Review of key planning and building policies 12 2.1 Building systems 12 2.2 Planning systems 13 2.3 State ESD policies and regulations 14 2.3.1 Victoria 15 2.3.2 New South Wales 15 2.3.3 Australia Capital Territory (ACT) 16 2.3.4 Queensland 16 2.3.5 South Australia 17 2.3.6 Western Australia 17 3. Planning decision making in Victoria: ESD in VCAT decisions 18 3.1 Stage 1: Identify all VCAT cases that have coverage of sustainability issues within the written reasons for the decision. -

The Benefits of Polymers for Australia's Built Environment

AUSTRALIAN MODERN BUILDING ALLIANCE Safe and sustainable construction with polymers The benefits of polymers for Australia’s built environment The benefits of polymers for Australia’s built environment This information sheet explains how polymer-based construction products create modern buildings that are durable, safe, sustainable and energy efficient. Polymers in the construction industry Polymers form the basis of many construction materials that are integral to modern buildings such as foams, paints, sealants, rubbers and plastics. These materials cover a broad range of products and applications for building interiors and exteriors including insulation, piping, flooring, wiring, window installation, solar modules, ventilation systems, awnings, painting, tiling and landscaping. The challenge According to the Australian particularly at a time when Whether in the construction, use Sustainable Built Environment Australia’s energy costs and or end-of-life phase, buildings Council (ASBEC), buildings in demands are increasing. consume vast volumes of energy Australia constructed after 2019 The performance and durability equating to large volumes of could make up more than half of of construction products – greenhouse gases (GHG). the country’s total building stock particularly insulation – is key by 2050.3 The IEA recommends In Australia, our buildings to creating more energy efficient strengthening construction codes account for 19 per cent of total buildings. energy used and 18 per cent of to address the energy efficiency our total direct GHG emissions.1 of new buildings and those Products should be long lasting, This figure would be closer requiring major retrofits as an require low maintenance or 2 to 40 per cent of total GHG immediate priority. -

Proposed Program of High Capacity Transit Improvements City of Atlanta DRAFT

Proposed Program of High Capacity Transit Improvements City of Atlanta DRAFT Estimated Capital Cost (Base Year in Estimated O&M Cost (Base Year in Millions) Millions) Project Description Total Miles Local Federal O&M Cost Over 20 Total Capital Cost Annual O&M Cost Share Share Years Two (2) miles of heavy rail transit (HRT) from HE Holmes station to a I‐20 West Heavy Rail Transit 2 $250.0 $250.0 $500.0 $13.0 $312.0 new station at MLK Jr Dr and I‐285 Seven (7) miles of BRT from the Atlanta Metropolitan State College Northside Drive Bus Rapid Transit (south of I‐20) to a new regional bus system transfer point at I‐75 7 $40.0 N/A $40.0 $7.0 $168.0 north Clifton Light Rail Four (4) miles of grade separated light rail transit (LRT) service from 4 $600.0 $600.0 $1,200.0 $10.0 $240.0 Contingent Multi‐ Transit* Lindbergh station to a new station at Emory Rollins Jurisdicitional Projects I‐20 East Bus Rapid Three (3) miles of bus rapid transit (BRT) service from Five Points to 3 $28.0 $12.0 $40.0 $3.0 $72.0 Transit* Moreland Ave with two (2) new stops and one new station Atlanta BeltLine Twenty‐two (22) miles of bi‐directional at‐grade light rail transit (LRT) 22 $830 $830 $1,660 $44.0 $1,056.0 Central Loop service along the Atlanta BeltLine corridor Over three (3) miles of bi‐directional in‐street running light rail transit Irwin – AUC Line (LRT) service along Fair St/MLK Jr Dr/Luckie St/Auburn 3.4 $153 $153 $306.00 $7.0 $168.0 Ave/Edgewood Ave/Irwin St Over two (2) miles of in‐street bi‐directional running light rail transit Downtown – Capitol -

Smart Urban Spaces Optimising Design for Comfort, Safety and Economic Vitality

Smart Urban Spaces Optimising design for comfort, safety and economic vitality Urban planners often ponder over the ways in which people will move through their designs, interact with the environment and with each other, and how best to utilise the spaces provided. Buro Happold’s Smart Space team have proven track record in optimising design of urban spaces and masterplans to enhance Capacity expansion of Makkah during Hajj visitor experience. We understand the benefits obtained from efficient layouts, intuitive wayfinding, and effective operational management. Madinah masterplan, optimising building massing to maximise shading comfort Our consultants enable a better understanding of the impacts of designs. Through the forecasting of movement and activity patterns, tailored to the specific use, our pedestrian flow modelling informs design and management in order to optimise the use of urban spaces and enhance user experience. The resulting designs are therefore extensively tested with a minimised risk of undesirable and/or unsafe congestion. We help clients better understand existing activity patterns Cardiff city centre masterplan and/or visitor preferences. With a holistic look at pedestrian and Footfall analysis of St Giles Circus, London vehicular desire lines, we can formulate a strategy to encourage footfall through the new developments. Accurate modelling provides a basis on which to assess potential risks and implement counter measures to negative factors such as poor access, fear of crime, inadequate parking facilities and lack of signage. In addition, it allows us to optimise the placement of activities – for example, placing retail in areas where the most footfall is expected; identifying appropriate spaces to locate other social activities; etc. -

Global Design Sprints: How to Reimagine Our Streets in an Era of Autonomous Vehicles

GLOBAL DESIGN SPRINTS: HOW TO REIMAGINE OUR STREETS IN AN ERA OF AUTONOMOUS VEHICLES OUTCOMES FROM CITIES AROUND THE WORLD URBAN STREETS IN THE AGE OF AUTONOMOUS VEHICLES CONTENTS - 2017 - GLOBAL DESING SPRINT OUTCOMES 2 Global Design Sprints - 2017 URBAN STREETS IN THE AGE OF AUTONOMOUS VEHICLES 1. INTRODUCTION Technological advancement for autonomous vehicles accelerated in 2015 Using this format, we hosted a series of global events to speculate and The following report is the result of this series of Global Design Sprints and, suddenly, everyone was talking about a future of autonomous and brainstorm the question of : – a collaboration of 138 sprinters from across the world. The executive connected vehicles. At BuroHappold, we wanted to understand what summary compares the different discussions and outcomes of the Sprints it might mean for our cities. How will our cities be impacted? Will there ‘HOW CAN URBAN STREETS BE RECLAIMED AND REIMAGINED and summarizes some of the key takeaways we collected. The ideas that be more or less traffic? Which ownership model for autonomous and THROUGH THE INTRODUCTION OF CONNECTED AND emerged range from transforming a residential neighbourhood from a car- connected vehicles will prevail? These are questions that many have asked, AUTONOMOUS VEHICLES?‘ zone to a care-zone to the introduction of the flexible use of a road bridge but no one can really answer today – even with the most sophisticated based on the demand from commuters, tourists, cyclists, and vehicular forecasting models. We cannot predict how people will respond to such a By bringing together people from the technology sector, the urban traffic. -

Ecodistricts Organization Engagement and Governance June 2011, Version 1.1

EcoDistricts Organization Engagement and Governance June 2011, Version 1.1 www.pdxinstitute.org/ecodistricts Copyright Copyright © 2011 Portland Sustainability Institute. All rights reserved. Acknowledgements The EcoDictricts Toolkits were developed by the Portland Sustainability Institute (PoSI) in partnership with practitioners from the EcoDistricts Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) in 2010-2011. Its publication would not have been possible without the dedication of these many volunteers. PoSI staff led the development, writing and research. TAC members reviewed draft toolkits and, in some cases, provided content. In addition, a targeted group of topic area experts provided a peer review. PoSI would like to thank the following individuals and organizations for their contributions and dedication to this process: Organization Working Group Jim Johnson (Chair), Oregon Solutions Paul Leistner, Portland Office of Neighborhood Involvement Jill Long, Lang Powell Tim O’Neal, Southeast Uplift Ethan Seltzer, Portland State University EcoDistricts Toolkit Organization Development, June 2011, Version 1.1 2 Contents Introduction .................................................................................... 4 Phase 1 – Engagement.................................................................. 6 Step 1. Engaging Stakeholders .................................................................6 Determine Representatives in Your Community...........................6 Make an Inventory of Community Resources.................................7 Define -

Climate Change, Scale, and Devaluation: the Challenge of Our Built Environment

Climate Change, Scale, and Devaluation: The Challenge of Our Built Environment Nathan F. Sayre * Abstract Climate debate and policy proposals in the United States have yet to grasp the gravity and magnitude of the challenges posed by global warming. This paper develops three arguments to redress this situation. First, the spatial and temporal scale of the processes linking greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to climate change is unprecedented in human experience, challenging our abilities to comprehend, let alone act. An adequate understanding of the scale of global warming leads to an unequivocal starting point for all discussions: we must leave as much fossil fuel in the ground as possible, for as long as possible. Second, a policy informed by this insight must focus on the built environment, which mediates economic production, exchange, and consumption in ways that both presuppose and reinforce high rates of GHG emissions, especially in the U.S. A rapid and comprehensive reconfiguration of the built environment is imperative if we are to mitigate and adapt to global warming. Third, the obstacles and opposition to such a reconfiguration are best understood in terms of the devaluation of fixed capital, public and private investments alike, that has been sunk in the built environment of the present. In a fortuitous paradox, these investments are threatened with devaluation whether or not we act to stabilize the atmospheric GHG concentrations; in highly uneven, unpredictable, and potentially abrupt ways, global warming will make our current built environment increasingly untenable and uneconomical. There is, therefore, no reason not to be proactive and to craft policies with the goal of completely redesigning and rebuilding our built environment over the next 20 to 50 years. -

Read the SPUR 2012-2013 Annual Report

2012–2013 Ideas and action Annual Report for a better city For the first time in history, the majority of the world’s population resides in cities. And by 2050, more than 75 percent of us will call cities home. SPUR works to make the major cities of the Bay Area as livable and sustainable as possible. Great urban places, like San Francisco’s Dolores Park playground, bring people together from all walks of life. 2 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 3 It will determine our access to economic opportunity, our impact on the planetary climate — and the climate’s impact on us. If we organize them the right way, cities can become the solution to the problems of our time. We are hard at work retrofitting our transportation infrastructure to support the needs of tomorrow. Shown here: the new Transbay Transit Center, now under construction. 4 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 5 Cities are places of collective action. They are where we invent new business ideas, new art forms and new movements for social change. Cities foster innovation of all kinds. Pictured here: SPUR and local partner groups conduct a day- long experiment to activate a key intersection in San Francisco’s Mid-Market neighborhood. 6 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 7 We have the resources, the diversity of perspectives and the civic values to pioneer a new model for the American city — one that moves toward carbon neutrality while embracing a shared prosperity. -

Integrating Infill Planning in California's General

Integrating Infill Planning in California’s General Plans: A Policy Roadmap Based on Best-Practice Communities September 2014 Center for Law, Energy & the Environment (CLEE)1 University of California Berkeley School of Law 1 This report was researched and authored by Christopher Williams, Research Fellow at the Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law. Ethan Elkind, Associate Director of Climate Change and Business Program at CLEE, served as project director. Additional contributions came from Terry Watt, AICP, of Terrell Watt Planning Consultant, and Chris Calfee, Senior Counsel; Seth Litchney, General Plan Guidelines Project Manager; and Holly Roberson, Land Use Council at the California Governor’s Office of Planning and Research (OPR), among other stakeholder reviewers. 1 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 1 Land Use Element ................................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Find and prioritize infill types most appropriate to your community .......................................... 5 1.2 Make an inclusive list of potential infill parcels, including brownfields ....................................... 9 1.3 Apply simplified mixed-use zoning designations in infill priority areas ...................................... 10 1.4 Influence design choices to -

4U60 Storage Enclosure Site Requirements Document

Site Requirements Document 4U60 Storage Enclosure G460-J-12 November 2015 1ET0164 Revision 1.1 Long Live Data ™ | www.hgst.com Site Requirements Document Copyright Copyright The following paragraph does not apply to the United Kingdom or any country where such provisions are inconsistent with local law: HGST a Western Digital company PROVIDES THIS PUBLICATION "AS IS" WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EITHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. Some states do not allow disclaimer or express or implied warranties in certain transactions, therefore, this statement may not apply to you. This publication could include technical inaccuracies or typographical errors. Changes are periodically made to the information herein; these changes will be incorporated in new editions of the publication. HGST may make improvements or changes in any products or programs described in this publication at any time. It is possible that this publication may contain reference to, or information about, HGST products (machines and programs), programming, or services that are not announced in your country. Such references or information must not be construed to mean that HGST intends to announce such HGST products, programming, or services in your country. Technical information about this product is available by contacting your local HGST representative or on the Internet at: support.hgst.com HGST may have patents or pending patent applications covering subject matter in this document. The furnishing of this document does not give you any license to these patents. © 2015 HGST, Inc. All rights reserved. HGST, a Western Digital company 3403 Yerba Buena Road San Jose, CA 95135 Produced in the United States Long Live Data™ is a trademark of HGST, Inc. -

WMATA State of Good Repair Years of Underfunding and Tremendous

RECOMMENDATIONS WMATA State of Good Repair Years of underfunding and tremendous regional growth have resulted in underinvestment and significant deterioration of the Washington Metrorail’s core transit infrastructure and assets, creating substantial obstacles to consistently delivering safe, reliable, and resilient service to its customers. In an effort to bring the system up to a state of good repair, WMATA created Momentum, a strategic 10-year plan that has set short-term and long-term actions to accelerate core capital investment in state of good repair and sustain investment into the future. Momentum identifies a $6 billion list of immediate and critical capital investments, called Metro 2025, aimed at (1) maximizing the existing rail system by operating all 8-car trains during rush hour, (2) improving high-volume rail transfer stations and underground pedestrian connections, (3) enhancing bus service, (4) restoring peak service connections, (5) integrating fare technology across the region’s multiple transit operators and upgrading communication systems, (6) expanding the bus fleet and storage and maintenance facilities, and (7) improving the flexibility of the transit infrastructure. With the first capital investment alone, WMATA estimates a capacity increase of 35,000 more passengers per hour during rush hour, which is the equivalent of building 18 new lanes of highway in Washington, DC. The second investment is a “quick win” to relieve crowding in the system’s largest bottlenecks and bring its most valuable core infrastructure up to a state of good repair. MTA Transportation Reinvention Commission Report ~ 31 ~ RECOMMENDATIONS Improving the System: Régie Autonome des Transports Parisiens (RATP) and Transport for London (TfL) Major cities around the world, notably London and Paris, are investing in their core system by maintaining and renewing their assets. -

ULI: Returns on Resilience the Business Case

Returns on Resilience THE BUSINESS CASE Cover photo: A view of the green roof and main office tower at 1450 Brickell Avenue, with Biscayne Bay beyond. Robin Hill © 2015 Urban Land Institute 1025 Thomas Jefferson Street, NW Suite 500 West Washington, DC 20007-5201 All rights reserved. Reproduction or use of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission of the copyright holder is prohibited. Recommended bibliographic listing: Urban Land Institute: Returns on Resilience: The Business Case. ULI Center for Sustainability. Washington, D.C.: the Urban Land Institute, 2015. ISBN: 978-0-87420-370-7 Returns on Resilience THE BUSINESS CASE Project Director and Author Sarene Marshall Primary Author Kathleen McCormick This report was made possible through the generous support of The Kresge Foundation. Center for Sustainability About the Urban Land Institute The mission of the Urban Land Institute is to provide leadership in the responsible use of land and in creating and sustaining thriving communities worldwide. Established in 1936, the Institute today has more than 35,000 members worldwide representing the entire spectrum of the land use and development disciplines. ULI relies heavily on the experience of its members. It is through member involvement and information resources that ULI has been able to set standards of excellence in development practice. The Institute has long been recognized as one of the world’s most respected and widely quoted sources of objective information on urban planning, growth, and development. ULI SENIOR