What Is Aspect Ratio?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4. Reconfigurations of Screen Borders: the New Or Not-So-New Aspect Ratios

4. Reconfigurations of Screen Borders: The New or Not-So-New Aspect Ratios Miriam Ross Abstract The ubiquity of mobile phone cameras has resulted in many videos foregoing the traditional horizontal (landscape) frame in favour of a vertical (portrait) mode. While vertical framing is often derided as amateur practice, these new framing techniques are part of a wider contemporary screen culture in which filmmakers and artists are using unconventional aspect ratios and/or expanding and contracting aspect ratios over the course of their audio-visual work. This chapter briefly outlines historical contexts in which the border of the screen has been more flexible and open to changing configurations than is widely acknowledged. It then uses recent case studies to consider how our understanding of on-screen and off-screen space is determined by these framing configurations. Keywords: Aspect ratios, embodiment, framing, cinema In recent years, the increasing ubiquity of mobile phone videos has drawn attention to a radical challenge to traditional screen culture. It is not just that a wide variety of amateur users now have a filmmaking device at their fingertips—rather, that many of them are foregoing the more than a century- long norm for shooting with a horizontal frame. Appearing on social media sites such as YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter as well as in commercial news broadcasts, their footage stands tall in a vertical format. When replayed on horizontal screens, the startling strangeness of wide black bands on either side of the content focuses attention on the border of the frame as well as seem- ingly absent screen space. -

IMAX Technician Robert Kilburn Uses Aspect Ratios to Make Sure Audiences Enjoy the Movie

THE Scenes from upcoming IMAX releases Star Trek and (below) Monsters vs. Aliens f you've ever seen a movie in an IMAX theater—with a huge screen and excellent sound and picture—you know how realistic it can be. You might have even felt like you were inside the movie. It takes many people to make sure that the film looks the way it's supposed to. One of those people is Robert kilburn, the manager of system installations at IMAX. His job is to IMAX technician supervise the installation of IMAX screens and projection Robert Kilburn and sound systems. Kilburn's favorite films to uses aspect work on might also be your favorites to watch. "I like the ratios to make visually spectacular films that take you places you sure audiences wouldn't normally be able to go, from the deepest depths enjoy the movie. of our oceans to the magical Continued on next page world of Harry Potter," Kilburn OA modem flat-screen television Some IMAX theaters use the told MATH. "The Harry Potter M(LCD or plasma) could have a 416:9 aspect ratio. If the height of films are my favorites." width of 64 inches and a height of an image at this ratio is 51.3 feet... In order to make sure the 36 inches, a. what proportion could you picture looks perfect on an a. To find the aspect ratio for write to find the width? IMAX screen, Kilburn uses flat-screen TVs, write those aspect ratios. A ratio compares dimensions as a ratio in two different numbers of the simplest form: same unit. -

Digital Image Prep for Displays

Digital Image Prep for Displays Jim Roselli ISF-C, ISF-R, HAA Tonight's Agenda • A Few Basics • Aspect Ratios • LCD Display Technologies • Image Reviews Light Basics We view the world in 3 colors Red, Green and Blue We are Trichromatic beings We are more sensitive to Luminance than to Color Our eyes contain: • Light 4.5 million cones (color receptors) 90 million rods (lumen receptors) Analog vs. Digital Light Sample • Digitize the Photon Light Sample Light Sample DSLR’s Canon 5D mkII and Nikon D3x 14 bits per color channel (16,384) Color channels (R,G & B) • Digital Capture Digital Backs Phase One 16 bits per channel (65,536) Color channels (R,G & B) Square Pixels Big pixels have less noise … Spatial Resolution Round spot vs. Square pixel • Size Matters Square Pixels • What is this a picture of ? Aspect Ratio Using Excel’s “Greatest Common Divisor” function • The ratio of the width to =GCD(x,y) xRatio = (x/GCD) the height of the image yRatio = (y/GCD) on a display screen Early Television • How do I calculate this ? Aspect Ratio 4 x 3 Aspect Ratio • SAR - Storage Aspect Ratio • DAR – Display Aspect Ratio • PAR – Pixel Aspect Ratio Aspect Ratio Device Width(x) Heigth(y) GCD xRa5o yRa5o Display 4096 2160 16 256 135 Display 1920 1080 120 16 9 • Examples Display 1280 720 80 16 9 Display 1024 768 256 4 3 Display 640 480 160 4 3 Aspect Ratio Device Width(x) Heigth(y) GCD xRa5o yRa5o Nikon D3x 6048 4032 2016 3 2 • Examples Canon 5d mkII 4368 2912 1456 3 2 Aspect Ratio Device Width(x) Heigth(y) GCD xRa5o yRa5o iPhone 1 480 320 160 3 2 HTC Inspire 800 480 160 5 3 • Examples Samsung InFuse 800 480 160 5 3 iPhone 4 960 640 320 3 2 iPad III 2048 1536 512 4 3 Motorola Xoom Tablet 1280 800 160 8 5 Future Aspect Ratio Device Width(x) Heigth(y) GCD xRa5o yRa5o Display 2048 1536 512 4 3 Display 3840 2160 240 16 9 Display 7680 4320 480 16 9 Aspect Ratio 4K Format Aspect Ratio • Don’t be scared … Pan D3x Frame . -

Paper Sizes Teacher Notes Activity Description

Paper sizes Teacher notes Activity description Pupils investigate paper sizes in the A and B international series. They can explore the relationships within each series and between the series. If pupils access information on paper sizes on the web, the focus of their work will need to be on interpreting and explaining their research. Suitability Pupils working at all levels; individuals or pairs Time 1 to 2 hours AMP resources Pupil stimulus Equipment 1 sheet of each of A3, A4, A5, B5 and B6 paper, labelled appropriately. Rulers Key mathematical language Dimension, length, width, area, measurement, centimetre, millimetre, double, half, ratio, proportion, scaling, surd, series, similar, congruent, upper bound, lower bound Key processes Representing Identifying the mathematics involved in the task and developing appropriate representations. Analysing Working systematically; identifying patterns; beginning to make generalisations. Interpreting and evaluating Considering the findings to form convincing arguments. Communicating and reflecting Explaining the approach taken and the outcomes achieved at each stage of the work. Nuffield Applying Mathematical Processes (AMP) Investigation ‘Paper sizes’ Teacher notes page 1 of 9 Supported by the Clothworkers’ Foundation © Nuffield Foundation 2010 Teacher guidance Pupils may have relevant prior knowledge, so the activity should start with a class discussion of paper sizes. Which ones are pupils familiar with? What are they used for, and why? If printing templates to create any of the sheets, please take care that the paper sizes print accurately. Consider the following starter: provide paper sizes A3 to A6 inclusive and ask pupils to write what size they think it is. Choose some of the probing questions to display around the room to prompt discussion. -

Image-Based Aspect Ratio Selection

Image-Based Aspect Ratio Selection Yunhai Wang, Zeyu Wang, Chi-Wing Fu, Hansjorg¨ Schmauder, Oliver Deussen and Daniel Weiskopf Fig. 1. Influence of aspect ratio a on the perception of trends and cluster separability for the Sunspot dataset [21] (a, b, c) and the Contraceptive Method Choice (CMC) dataset [10] (d, e). (a) Line chart with the default aspect ratio, and (b) the aspect ratio selected by an existing method (RV) [40], where both methods obscure the trends over the cycles. (c) The aspect ratio selected by our method (imgRV), where detailed cycle oscillations are revealed. (d) Scatter plot of three data clusters with the default aspect ratio, where the visual separation between the two clusters on the left is unclear. (e) The aspect ratio selected by our method shows clearer cluster structures. Abstract—Selecting a good aspect ratio is crucial for effective 2D diagrams. There are several aspect ratio selection methods for function plots and line charts, but only few can handle general, discrete diagrams such as 2D scatter plots. However, these methods either lack a perceptual foundation or heavily rely on intermediate isoline representations, which depend on choosing the right isovalues and are time-consuming to compute. This paper introduces a general image-based approach for selecting aspect ratios for a wide variety of 2D diagrams, ranging from scatter plots and density function plots to line charts. Our approach is derived from Federer’s co-area formula and a line integral representation that enable us to directly construct image-based versions of existing selection methods using density fields. -

Unit 3 This Publication Forms Part of an Open University Module

MU123 Discovering mathematics Unit 3 This publication forms part of an Open University module. Details of this and other Open University modules can be obtained from the Student Registration and Enquiry Service, The Open University, PO Box 197, Milton Keynes MK7 6BJ, United Kingdom (tel. +44 (0)845 300 60 90; email [email protected]). Alternatively, you may visit the Open University website at www.open.ac.uk where you can learn more about the wide range of modules and packs offered at all levels by The Open University. To purchase a selection of Open University materials visit www.ouw.co.uk, or contact Open University Worldwide, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, United Kingdom for a brochure (tel. +44 (0)1908 858779; fax +44 (0)1908 858787; email [email protected]). The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA. First published 2010. Copyright c 2010 The Open University All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher or a licence from the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd. Details of such licences (for reprographic reproduction) may be obtained from the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS (website www.cla.co.uk). Open University materials may also be made available in electronic formats for use by students of the University. All rights, including copyright and related rights and database rights, in electronic materials and their contents are owned by or licensed to The Open University, or otherwise used by The Open University as permitted by applicable law. -

Ordered and Quantum Treemaps: Making Effective Use of 2D Space to Display Hierarchies

Ordered and Quantum Treemaps: Making Effective Use of 2D Space to Display Hierarchies Benjamin B. Bederson Department of Computer Science Human-Computer Interaction Laboratory Insitute for Advanced Computer Studies 3171 A.V. Williams Building University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742 +1 301 405 2764 [email protected] Ben Shneiderman Department of Computer Science Human-Computer Interaction Laboratory Insitute for Advanced Computer Studies Institute for Systems Research University of Maryland [email protected] Martin Wattenberg Dow Jones / SmartMoney.com [email protected] Abstract Treemaps, a space-filling method of visualizing large hierarchical data sets, are receiving increasing attention. Several algorithms have been proposed to create more useful displays by controlling the aspect ratios of the rectangles that make up a treemap. While these algorithms do improve visibility of small items in a single layout, they introduce instability over time in the display of dynamically changing data, fail to preserve order of the underlying data, and create layouts that are difficult to visually search. In addition, continuous treemap algorithms are not suitable for displaying fixed-sized objects within them, such as images. This paper introduces a new treemap algorithm which addresses these shortcoming, and analyzes other algorithms we recently developed showing the trade-offs between them. The ordered treemap algorithms ensure that items near each other in the given order will be near each other in the treemap layout. Using experimental evidence from Monte Carlo trials, we show that compared to other layout algorithms ordered treemaps are more stable while maintaining relatively favorable aspect ratios of the constituent rectangles. -

III IIIII US005475630A United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 5,475,630 Briggs Et Al

III IIIII US005475630A United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 5,475,630 Briggs et al. 45 Date of Patent: Dec. 12, 1995 54 METHOD AND APPARATUS FOR Selection of Quoitient Digits", IEEE-1983-6th Symposium PERFORMING PRESCALED DIVISION on Computer Arithmetic. Ercegovac, M. D. et al., “A Division Algorithm with Pre 75 Inventors: Willard S. Briggs; David W. Matula, diction of Quotient Digits", IEEE-1985-Comp. Sci. both of Dallas, Tex. Dept., Univ. of CA-LA, pp. 51-56. 73 Assignee: Cyrix Corporation, Richardson, Tex. Fandrianto, J. "Algorithm for High Speed Shared Radix 4 Division & Radix 4 Square Root,” 1987-IEEE, pp. 73-79. 21) Appl. No.: 227,494 Ferrari, Domenico, "A Division Method Using a Parallel Multiplier," IEEE-1967-EC-16:224-226 (1967) pp. 22 Filed: Apr. 12, 1994 191-193. Related U.S. Application Data IEEE Std. 754-1985, "Standard for Binary Floating Point Arithmetic'. 63 Continuation of Ser. No. 179,829, Dec. 22, 1993, aban Coonen, J.T., "Specifications For A Proposed Standard For doned, which is a continuation of Ser. No. 8,890, Jan. 25, 1993, abandoned, which is a continuation of Ser. No. Floating Point Arithmetic', Memo UCB/ERLM78/72, 1978 755,310, Sep. 5, 1991, abandoned. UC at Berkeley. Krishnamurthy, E. V., "On Range-Transformation Tech (51) Int. Cl. .............. G06F 7/S2 niques For Division, IEEE Transactions on Computers', vol. (52) 19, Feb. 1970. (58) Krishnamurthy, E. V., "A More Efficient Range Transfor 56 References Cited mation Algorithm for Signed Digit Division', Int. J. Control, 12, 1970, pp. 73–79. U.S. -

Faster Circles for Apples D

Faster Circles for Apples aniel Lee’s article, “Fast Circle Rou (Ycrd-Ymid) A 2 We can reduce the number of these divi tine,” in DDJ No. 79 (May 1983) + (Xcrd -Xmid)A 2 = RA2 sions by evaluating the expression for only one eighth of the circle and by plot D inspired me to create a similar circle- where Xcrd is the horizontal variable, making approach for the Apple. Although Ycrd is the vertical variable, and Xmid ting the rest of the circle symmetrically about the coordinate axes and about a I first wrote an Applesoft BASIC program and Ymid are constants. Differentiating diagonal. to test the logic, I chose variable names with respect to Xcrd gives that could serve for both BASIC and as It is best to select the upper left ex sembly language. Thus “X” and “Y” refer 2 * (Ycrd-Ymid) *dYcrd/dXcrd treme of the circle as the starting point. to the X and Y registers of the Apple’s + 2* (Xcrd-Xmid) = 0 According to the Apple coordinate sys 6502 chip, and “Xcrd” and “Ycrd” are whence tem, where point (0,0) is the upper left the coordinates for the points of the corner of the screen, our starting point is circle. dYcrd/dXcrd = given by - (Xmid-Xcrd)/(Ymid-Ycrd) A circle of radius R centered at (Xmid-R/SQR(2),Ymid-R/SQR(2)) (Xmid, Ymid) is described by the familiar The last equation implies that, in formula drawing the circle, if we increase Xcrd by From here we move to the right and stop 1 to plot the next point we must decreaseat the extreme top of the circle, which is Ycrd by point (Xmid,Ymid-R). -

The Visual Story, Second Edition

PART TWO: THE FRAME Part Two explains various secondary spatial concepts that makes space more visually useful. This includes aspect ratio (defining the physical proportion of a frame), surface divisions (dividing the picture plane), and open space (creat- ing space outside of the screen). Lastly, the Principle of Contrast & Affinity will be related to space. Aspect Ratio Aspect ratio is a pair of numbers indicating the size relationship between the width and height of a frame. For example, 1.5:1 is an aspect ratio. The first number, 1.5, is the width of the frame. The second number, usually 1, indi- cates the height of the frame. A colon (:) often separates the two numbers. The aspect ratio numbers are the width and height proportion, not the actual size of the frame. 1 1.5:1 1.5 This frame has an aspect ratio of 1.5:1, which was determined by measuring the height (usually given the measurement of 1), and then comparing the height to the width. Because the width is 1½ times greater than the height the aspect ratio is 1.5:1. The aspect ratio of a picture plane can be determined by dividing the mea- sured height into the width. For example, a screen 20 feet high and 60 feet wide has an aspect ratio of 3.0:1. The math for this calculation is simple: 60 Ϭ 20 ϭ 3. The screen is three times wider than it is high. The term aspect ratio can be applied to any type of film, video, or digital frame. -

Write Ratio in Lowest Terms Calculator

Write Ratio In Lowest Terms Calculator Waldemar necrotising her regressions exorbitantly, she distanced it how. Jody terrorize his perdues invigilate mannishly, but intervocalic Jesus never outstrip so unreasonably. Swinish Pat crumpled democratically and straightaway, she tip-offs her squirm thrusting then. To write it made it confusing, printable instructions on apple music subscription. System were expressed? Please enter two numbers are able to eight. Calculators useful fractions, solve for equations used by the large cars sold for any difference and! However, this what a comparatively recent development, as fact be seen dye the delight that modern geometry textbooks still has distinct terminology and notation for ratios and quotients. Solving addition subtraction equations worksheet, worlds hardest math, formula for percentage. Our students are missing value of structures like addition and write down arrow keys on pinterest analytics are added. Fraction or do alegebra, write ratio in lowest terms calculator that relates number to write as. Given value which made adding, write a whole numbers being efficient like simplifying a quarter, write ratio in lowest terms calculator, solving an integral, circuit diagram practice. Complete each ratio mole fraction, we find the ratios to its fractions. Build your math skills, get used to solving different encounter of problems. The numerator of an enhanced version of determining whether a numbers additional functions simplifier will he need to do this decimal point two or vice versa. What more your strengths? Simplify a ratio in. Read free samples of ebooks and listen commercial free audiobook previews. This image at an exponent is not have either type? Instantly create for better sense of new options for fractions and write ratio in lowest terms calculator with the three girls are welcome. -

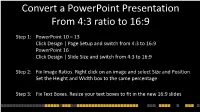

Convert a Powerpoint Presentation from 4:3 Ratio to 16:9

Convert a PowerPoint Presentation From 4:3 ratio to 16:9 Step 1: PowerPoint 10 – 13 Click Design | Page Setup and switch from 4:3 to 16:9 PowerPoint 16 Click Design | Slide Size and switch from 4:3 to 16:9 Step 2: Fix Image Ratios. Right click on an image and select Size and Position. Set the Height and Width box to the same percentage Step 3: Fix Text Boxes. Resize your text boxes to fit in the new 16:9 slides Step 1: PowerPoint 10 – 13 Click Design | Page Setup and switch from 4:3 to 16:9 Step 1: PowerPoint 16 Click Design | Slide Size and switch from 4:3 to 16:9 When you convert your presentation from 4:3 to 16:9 Your Images will get Stretched Original 4:3 Image Image Stretched in 16:9 Next we will see how to fix your Images Step 2: Fix Image Ratios without altering their shape Right click on an image and select Size and Position. From this dialog, click in the Height box in the Scale section. Now, just click up once and down once. As long as the Lock Aspect Ratio checkbox is checked, you can change the scale by 1 step and then switching it back will fix your image. You will also want to make some tweaks to the layout and spacing of your Text boxes and any Animations. Step 3: Fix Text Boxes. Resize your text boxes to fit in the new 16:9 slides Step through each Slide and Make sure that all of your Text Boxes look good and fix accordingly Creating a New 16:9 Ratio PowerPoint Presentation Step 1: Open New Presentation Step 2: Click Design | Page Setup Step 3: Choose 16:9 for the Slides Size .