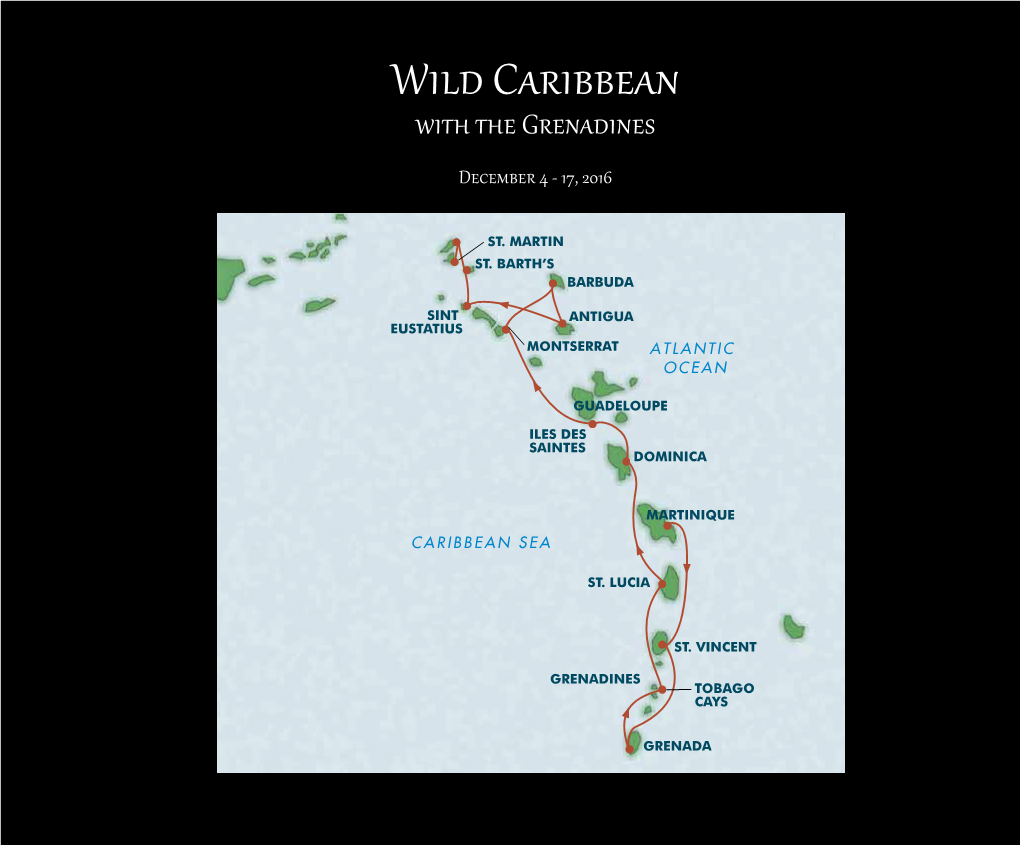

Wild Caribbean with the Grenadines December 4 - 17, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Refuge Update March/April 2007 Vol 4, No 2

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service National Wildlife Refuge System Inside RefugeUpdate March/April 2007 Vol 4, No 2 What’s Melting: Togiak Refuge Sizes Up Its Glaciers, page 3 The refuge is measuring changes Where the Buffalo Roam in the size of several dozen glaciers that are especially sensitive to warming trends. Focus on Fish Conservation, pages 10-15 The spoiling of habitat is still the greatest of privations to fish and wildlife, a nexus point for Fisheries and the Refuge System. Whatever happened to…, pages 16-17 An update on Update stories, taking you to the conclusion. Wildlife Cooperatives, page 20 Wildlife cooperatives have evolved as one more way to operate in the greater geographic and political landscape. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is using a new genetics-based approach to manage herds of bison. As part of the new approach, more than 100 animals are being moved around National Wildlife Refuge System lands in five states. (USFWS) he U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Early in December 2006, 39 bison from Tis changing the way it manages an the Sullys Hill herd were moved to Fort icon of the American west – the bison. Niobrara National Wildlife Refuge in First Lady Tours Midway “Instead of managing individual herds, Nebraska. A week later, seven animals we are moving to manage the Service’s were moved from the National Bison Atoll Refuge herds as one resource,” says Paul Halko, Range in Montana to Sullys Hill. Thirty- refuge manager at Sullys Hill National nine bison were also moved from the First Lady Laura Bush, pictured Game Preserve in North Dakota. -

Inside the Volcano – a Curriculum on Nicaragua

Inside the Volcano: A Curriculum on Nicaragua Edited by William Bigelow and Jeff Edmundson Network of Educators on the Americas (NECA) P.O. Box 73038 Washington, DC 20056-3038 Network of Educators' Committees on Central America Washington, D.C. About the readings: We are grateful to the Institute for Food and Development Policy for permission to reproduce Imagine You Were A Nicaraguan (from Nicaragua: What Difference Could A Revolution Make?), Nicaragua: Give Change a Chance, The Plastic Kid (from Now We Can Speak) and Gringos and Contras on Our Land (from Don’t Be Afraid, Gringo). Excerpt from Nicaragua: The People Speak © 1985 Bergin and Garvey printed with permission from Greenwood Press. About the artwork: The pictures by Rini Templeton (pages 12, 24, 26, 29, 30, 31, 38, 57 60, 61, 66, 74, 75, 86, 87 90, 91. 101, 112, and the cover) are used with the cooperation of the Rini Templeton Memorial Fund and can be found in the beautiful, bilingual collection of over 500 illustrations entitled El Arte de Rini Templeton: Donde hay vida y lucha - The Art of Rini Templeton: Where there is life and struggle, 1989, WA: The Real Comet Press. See Appendix A for ordering information. The drawing on page 15 is by Nicaraguan artist Donald Navas. The Nicaraguan Cultural Alliance has the original pen and ink and others for sale. See Appendix A for address. The illustrations on pages 31, 32 and 52 are by Nicaraguan artist Leonicio Saenz. An artist of considerable acclaim in Central America, Saenz is a frequent contributor to Nicar&uac, a monthly publication of the Nicaraguan Ministry of Culture. -

Real Affordable Costa Rica 2017 14-Day Land Tour{Tripoperatedby}

Real Affordable Costa Rica 2017 14-Day Land Tour{TRIPOperatedBy} EXTEND YOUR TRIP PRE-TRIPS Guatemala: Antigua & Tikal OR Nicaragua's Colonial Cities & Volcanic Landscapes POST-TRIP Tortuguero National Park: Ultimate Rain Forest Experience Your Day-to-Day Itinerary OVERSEAS ADVENTURE TRAVEL Overseas Adventure Travel, founded in 1978, is America’s leading adventure travel company. The New York Times, Condé Nast Traveler, The Los Angeles Times, Travel + Leisure, The Wall Street Journal, US News & World Report, and others have recommended OAT trips. But our most im- pressive reviews come from our customers: Thousands of travelers have joined our trips, and 95% of them say they’d gladly travel with us again, and recommend us to their friends. INCLUDED IN YOUR PRICE » International airfare, airport transfers, government taxes, fees, and airline fuel surcharges unless you choose to make your own air arrangements » All land transportation » Accommodations for 13 nights » 31 meals—daily breakfast, 9 lunches, 9 dinners (including 1 Home-Hosted Lunch) » 10 small group activities » Services of a local O.A.T. Trip Leader » Gratuities for local guides, drivers, and luggage porters » 5% Frequent Traveler Credit toward your next adventure—an average of $176 Itinerary subject to change. For information or reservations, call toll-free 1-800-955-1925. WHAT THIS TRIP IS LIKE PACING ACCOMMODATIONS & FACILITIES » 6 locations in 14 days with one 1-night » Some of our lodgings may be quite small stay and some early mornings or family-run » While this is a mobile -

Education Resource Service Catalogue 2012

Education Resource Service Catalogue 2012 1 ERS Catalogue 2012 This fully revised and updated catalogue is an edited list of our resources intended to provide customers with an overview of all the major collections held by the Education Resource Service (ERS). Due to the expansive nature of our collections it is not possible to provide a comprehensive holdings list of all ERS resources. Each collection highlights thematic areas or levels and lists the most popular titles. Our full catalogue may be searched at http://tinyurl.com/ERSCatalogue We hope that you find this catalogue helpful in forward planning. Should you have any queries or require further information please contact the ERS at the following address: Education Resource Service C/O Clyde Valley High School Castlehill Road Wishaw ML2 0LS TEL: 01698 403510 FAX: 01698 403028 Email: [email protected] Catalogue: http://tinyurl.com/ERSCatalogue Blog: http://ersnlc.wordpress.com/ 2 Your Children and Young People’s Librarian can….. The Education Resource Service is a central support service providing educational resources to all North Lanarkshire educational establishments. We also provide library based support and advice through our team of Children and Young People’s librarians in the following ways: Literacy • Information literacy activities • Effective use of libraries • Suggested reading lists • Author visits • Facilitate and lead storytelling sessions • Supporting literature circles • Transition projects Numeracy • Using the Dewey Decimal Classification System • Research skills • Transition projects Health and Wellbeing • Professional development resources • Reaction reading groups • Pupil librarians • Internet safety • Transition projects General • Pre-HMIe inspection support • Cross-curricular projects • Partnership working with public libraries, CL&D and other agencies 3 General Information Loan Period The normal loan period for all resources is 28 days. -

Oral and Cloacal Microflora of Wild Crocodiles Crocodylus Acutus and C

Vol. 98: 27–39, 2012 DISEASES OF AQUATIC ORGANISMS Published February 17 doi: 10.3354/dao02418 Dis Aquat Org Oral and cloacal microflora of wild crocodiles Crocodylus acutus and C. moreletii in the Mexican Caribbean Pierre Charruau1,*, Jonathan Pérez-Flores2, José G. Pérez-Juárez2, J. Rogelio Cedeño-Vázquez3, Rebeca Rosas-Carmona3 1Departamento de Zoología, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Distrito Federal 04510, Mexico 2Departamento de Salud y Bienestar Animal, Africam Safari Zoo, Puebla, Puebla 72960, Mexico 3Departamento de Ingeniería Química y Bioquímica, Instituto Tecnológico de Chetumal, Chetumal, Quintana Roo 77013, Mexico ABSTRACT: Bacterial cultures and chemical analyses were performed from cloacal and oral swabs taken from 43 American crocodiles Crocodylus acutus and 28 Morelet’s crocodiles C. moreletii captured in Quintana Roo State, Mexico. We recovered 47 bacterial species (28 genera and 14 families) from all samples with 51.1% of these belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae. Fourteen species (29.8%) were detected in both crocodile species and 18 (38.3%) and 15 (31.9%) species were only detected in American and Morelet’s crocodiles, respectively. We recovered 35 bacterial species from all oral samples, of which 9 (25.8%) were detected in both crocodile species. From all cloacal samples, we recovered 21 bacterial species, of which 8 (38.1%) were detected in both crocodile species. The most commonly isolated bacteria in cloacal samples were Aeromonas hydrophila and Escherichia coli, whereas in oral samples the most common bacteria were A. hydrophila and Arcanobacterium pyogenes. The bacteria isolated represent a potential threat to crocodile health during conditions of stress and a threat to human health through crocodile bites, crocodile meat consumption or carrying out activities in crocodile habitat. -

Wild Caribbean with the Grenadines

WILD CARIBBEAN WITH THE GRENADINES On our journey through the lesser-known Eastern Caribbean, we’ll venture to ports inaccessible to larger ships, affording you the chance for dazzling snorkeling, hiking, bird-watching—glimpse the St. Vincent parrot—and explorations of historic forts and peaceful colonial plazas. ITINERARY Day 1: Martinique Upon arrival, transfer to Le Cap Est Lagoon for dinner and overnight. 01432 507 280 (within UK) [email protected] | small-cruise-ships.com Day 2: Martinique / Embark Le Ponant view an idyllic waterfall. Martinique is home to a fascinating and dynamic mélange of French traditions and Caribbean Creole culture. Birders depart Day 5: Tobago Cays early for Presquile Caravelle National Park to search for such These five small, uninhabited islands are part of Tobago Cays island endemics as the Martinique oriole and white-breasted Marine Park. With pristine coral reefs, crystal-clear waters, and thrasher. Or, choose to visit Balata Church, a miniature version deserted white-sand beaches, this area is renowned for some of of the Basilica Montmartre in Paris, then continue to Domine the best snorkeling and diving in the Caribbean with vertical and d’Emeraude, a botanical garden and interpretive center devoted gently sloping walls, and multiple wrecks. to the island’s natural history. After lunch at a local restaurant, take a short drive through the ruins of St. Pierre, which was Day 6: St. Lucia destroyed in 1902 during a massive volcanic eruption. The tour Be on deck as the ship approaches St. Lucia for stunning views ends in Fort-de-France with a visit to the fascinating of the Pitons, two volcanic peaks rising more than 2,400 feet Pre-Columbian Museum and free time to peruse the shops or from the turquoise sea. -

Unique! Extras

Starters Mains £3.90 BREAD & OLIVES CURRIED GOAT (k) (g) £11.00 Marinated olives tossed with olive oil, lemon, black Delicious curried goat with scallion, onions and carrots, pepper and chilli. Served with crusty bread. served with white rice or rice’n’peas. £4.60 STAMP’N’GO JERK CHICKEN LEG (g) £8.50 Delicious fried Saltfish fritters served with red onion, Slow cooked jerked chicken leg in our home-made scallion, scotch bonnet, thyme and lemon. gravy, served with fried plantain, steamed vegetables B A E and rice’n’peas. (v) £4.30 R O U S PEPPER POT SOUP & C O O K H Add an extra piece of chicken. £3.00 Cabbage, carrots, onion,Starters chow chow, yam, potato, Mains Starters BREADhot pepper & OLIVES soup. Served with crusty bread. £3.90 Mains BREAD & OLIVES £3.90 CURRIED GOAT (k) (g) (k) (g) £11.00£10.00 CURRIED GOAT (k)(k) (g) Mains £11.00 BROWN STEW CHICKEN Starters Marinated olives tossed with olive oil, lemon, black CURRIED GOAT £11.00 £3.90 MarinatedBREAD & OLIVESolives tossed with oliveolive oil, lemon,lemon, blackblack (k) (g) Delicious curried goat with scallion, onions and carrots, pepper and chilli. Served Mainswith crusty bread. DeliciousCURRIED curried GOAT goatgoat0117 with scallion, 330 onions 5298 andand carrots,carrots, £11.00 Browned and stewed skinless soft and tender chicken Starters Marinated olives tossed with olive oil, lemon, black £3.90 pepper and chilli. Served with crusty bread. BREAD & OLIVES pepper and chilli. Served with crusty bread. CURRIEDMUSSELS GOAT(g) (k) (g) £11.00£6.00 servedDelicious with curried white goatrice orwith rice’n’peas. -

Nicaragua: the Threat of a Good Example?

DiannaMelrose First Published 1985 Reprinted 1986,1987,1989 ©Oxfam 1985 Preface © Oxfam 1989 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Melrose, Dianna Nicaragua: the threat of a good example. 1. Nicaragua. Economic conditions I. Title 330.97285'053 ISBN 0-85598-070-2 ISBN 0 85598 070 2 Published by Oxfam, 274 Banbury Road, Oxford, 0X2 7DZ, UK. Printed by Oxfam Print Unit OX196/KJ/89 This book converted to digital file in 2010 Contents Preface vii Introduction 1 Chronology of Political Developments 2 1. The Somoza Era 4 The Miskitos and the Atlantic Coast The 1972 Earthquake Land Expropriation Obstacles to Community Development The Somoza Legacy 2. A New Start for the People 12 The Literacy Crusade Adult Education New Schools Public Health Miners' Health Land Reform New Cooperatives Food Production Consumption of Basic Foods Loss of Fear The Open Prisons Obstacles to Development 3. Development Under Fire 27 Miskito Resettlement Programme Disruption of Development Work Resettlement of Displaced People Economic Costs of the Fighting 4. Debt, Trade and Aid 39 Debt Trade Aid 5. The Role of Britain and Europe 45 UK Bilateral Aid Other European Donors EEC Aid Trade A Political Solution Europe's Role 6. Action for Change: Summary and Recommendations 59 Notes and References Abbreviations Further Reading iii IV Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank all the Nicaraguan people who gener- ously gave their time to help with research for this book, particularly Oxfam friends and project-holders who gave invaluable assistance. -

Caribbean Sea Ecosystem Assessment (CARSEA)

Caribbean Sea Ecosystem Assessment (CARSEA) A contribution to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment prepared by the Caribbean Sea Ecosystem Assessment Team Co-ordinating Lead Authors JOHN B. R. AGARD AND ANGELA CROPPER Lead Authors Patricia Aquing, Marlene Attzs, Francisco Arias, Jesus Beltrán, Elena Bennett, Ralph Carnegie, Sylvester Clauzel, Jorge Corredor, Marcia Creary, Graeme Cumming, Brian Davy, Danielle Deane, Najila Elias-Samlalsingh, Gem Fletcher, Keith Fletcher, Keisha Garcia, Jasmin Garraway, Judith Gobin, Alan Goodridge, Arthur Gray, Selwin Hart, Milton Haughton, Sherry Heileman, Riyad Insanally, Leslie Ann Jordon, Pushpam Kumar, Sharon Laurent, Amoy Lumkong, Robin Mahon, Franklin McDonald, Jeremy Mendoza, Azad Mohammed, Elizabeth Mohammed, Hazel McShine, Anthony Mitchell, Derek Oderson, Hazel Oxenford, Dennis Pantin, Kemraj Parsram, Terrance Phillips, Ramón Pichs, Bruce Potter, Miran Rios, Evelia Rivera-Arriaga, Anuradha Singh, Joth Singh, Susan Singh-Renton, Lyndon Robertson, Steve Schill, Caesar Toro, Adrian Trotman, Antonio Villasol, Nicasio Vina-Davila, Leslie Walling, George Warner, Kaveh Zahedi, Monika Zurek Editorial Advisers Norman Girvan and Julian Kenny Editorial Consultant Tim Hirsch Sponsors: THE CROPPER FOUNDATION UWI Other Financial Contributors: MILLENNIUM ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT UNEP ROLAC i ii CARIBB. MAR. STUD., SPECIAL EDITION, 2007 Foreword We are very pleased to have the opportunity to combine our thoughts and concerns in a joint Foreword to this Report of the Caribbean Sea Ecosystem Assessment (CARSEA). This pleasure is, however, accompanied by a palpable anxiety about the findings of this Assessment, given the significance that this ecosystem has for the economic, social, and cultural well- being of the diversity of nations which make up the Wider Caribbean region, that this Report so clearly establishes. -

Spanish Direct Investment in Latin America: Challenges and Opportunities William Chislett

William Chislett Spanish Direct Investment in Latin America: Challenges and Opportunities William Chislett Challenges and Opportunities Spanish Direct Investment in Latin America: William Chislett was born in Oxford in 1951. He reported on Spain’s 1975-78 transition to democracy for The Times. Between 1978 and 1984 he was based in Mexico City for The Financial Times, covering Mexico and Central America, before returning to Madrid in 1986 as a writer and translator. He has written books on Spain, Portugal, Chile, Ecuador, Panama, Finland, El Salvador and Turkey for Euromoney Publications. The Writers and Scholars Educational Trust published his The Spanish Media since Franco in 1979. Banco Central Hispano published his book España: en busca del éxito in 1992 (originally published that same year by Euromoney), Spain: at a Turning Point in 1994, and Spain: the Central Hispano Handbook, a yearly review, between 1996 and 1998. Banco Santander Central Hispano published his dictionary of economic terms in 1999 and his Spain at a Glance in 2001. He wrote the section on Latin America for Business: The Ultimate Resource (Bloomsbury, 2002), and in 2002 the Elcano Royal Institute published his book The Internationalization of the Spanish Economy. He is married and has two sons. Praise for previous books on Spain One of the great attractions is the author’s capacity to gather, analyze and synthesize the most relevant economic information Spanish Direct Investment and explain its implications concisely and directly. in Latin America: Guillermo de la Dehesa, Chairman of the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), El País Challenges and Opportunities Stylish and impressive. -

A-Level Geography Pre-Year 12 Tasks

A-Level Geography Pre-Year 12 tasks Geography is a very complex subject which encompasses our everyday lives. As the recent events of 2020 have shown the globalisation and connectivity of people has resulted in this year being like none other in living memory. The world has essentially shut down… The Year 12 course starts with the following two topics: Population and the Environment (Human Geography) Water and Carbon Cycles (Physical Geography) Tasks for Population and the Environment This topic looks at how the population density and distribution of people on Earth is determined by the climate, water supply and soils in each biome. Within this there are many links to the spread of diseases, levels of development and population structure. Task 1: On the internet find 2 maps to show the population distribution and density of people on Earth, then find a map to show the global biomes. For each biome get a definition of the characteristics and key locations. Using the population distribution and density maps annotate the areas on Earth where most people are found. Do this for each continent, add on any large cities you know and physical features such as deserts and mountain ranges. When you have done this use the biome map and your annotated maps to see which biomes are able to support the largest numbers of people. Can you spot a trend? Task 2: Linking into Task 1, find a population density map of Egypt, then research its population and why it has such a distinctive pattern. Task 3: To show the link between the spread of disease and the population pick 2 of the following diseases and create a timeline to show the global spread through the human population. -

Hello Everyone, We Know That in This Time of Real Uncertainty, You Might

Hello Everyone, We know that in this time of real uncertainty, you might for once not want to sit indoors all day as the sun shines bright, and for many, you might actually be bored. We get that – it is perfectly acceptable and believe me, we adults are feeling just the same as you! So, to help pass the time over Easter especially, or when you have completed all your CW that is being set – please find below some different challenges and tasks that you can complete to help build your skills in Geography. Some you may find easier than others, and that’s ok – just move on to the next J We have also pulled together videos on Netflix (hopefully they still are!) or suggested films that you might like to watch – as always, please ensure your parent/guardian is happy for you to watch these first and they also review the age consent of the one/s you select – as these may have changed since we compiled the list. As always too, if you are watching something and you don’t like it – stop! Some of the films may provide the truth to how food is made for example, and some of you may not like this! Happy entertaining yourself J and Happy Easter when it comes! The Geography Team Skills Based Information and Worksheets (Just follow the links) https://fdslive.oup.com/www.oup.com/oxed/secondary/geography/ks3-geography-lfh- pack.pdf?region=uk OS Map Puzzles (Extracts from there books…) https://getoutside.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/guides/os-map-puzzles-to-challenge-your-skills/ Fun Educational Geography Quiz/s https://www.educationquizzes.com/ks3/geography/ A playlist of Geographical Programs to spark your interest: Tectonics: Ø The Impossible: True story about the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami: Available on Netflix 12 Ø 72 Dangerous Places to Live: Netflix.