Maritime Transportation in Latin America and the Caribbean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latin America and Caribbean Region LIST of ACRONYMS

Inclusive and Sustainable Industrial Development in Latin America and Caribbean Region LIST OF ACRONYMS ALBA Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas IPs Industrial Parks BIDC Barbados Investment and Development INTI National Institute of Industrial Corperation Technologies (Argentina) BRICS Brazil, Russian Federation, India, China ISID Inclusive and Sustainable Industrial and South Africa („emerging economies“) Development CAF Development Bank for Latin America ITPOs Investment and Technology Promotion CAIME High Level Centre for Research, Offices Training and Certification of Production LATU Technological Laboratory of Uruguay (Uruguayan Project) MERCOSUR Southern Common Market CAN Andean Community MoU Memorandum of Understanding CARICOM Caribbean Community ODS Ozone Depleting Substances CELAC Community of Latin American and OESC Organization of Eastern Caribbean States Caribbean States OFID OPEC Fund for International Development CFCs Chloro-Fluoro-Carbons PCBs Poly-Chlorinated Biphenyls CIU Uruguayan Chamber of Industries POPs Persistent Organic Pollutants CNI National Confederation of Brazil PPPs Public Private Partnerships COPEI Peruvian Committee on Small Industry RO Regional Office ECLAC Economic Commission for Latin America SDGs Sustainable Development Goals EU European Union SELA Latin American Economic System FAO Food and Agriculture Organization (UN SEZs Special Economic Zones System) SICA Central American Integration System GEF Global Environmental Facility SMEs Small and Medium-sized Enterprises GNIC Great Nicaraguan Interoceanic -

African Traditional Plant Knowledge in the Circum-Caribbean Region

Journal of Ethnobiology 23(2): 167-185 Fall/Winter 2003 AFRICAN TRADITIONAL PLANT KNOWLEDGE IN THE CIRCUM-CARIBBEAN REGION JUDITH A. CARNEY Department of Geography, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095 ABSTRACT.—The African diaspora to the Americas was one of plants as well as people. European slavers provisioned their human cargoes with African and other Old World useful plants, which enabled their enslaved work force and free ma- roons to establish them in their gardens. Africans were additionally familiar with many Asian plants from earlier crop exchanges with the Indian subcontinent. Their efforts established these plants in the contemporary Caribbean plant corpus. The recognition of pantropical genera of value for food, medicine, and in the practice of syncretic religions also appears to have played an important role in survival, as they share similar uses among black populations in the Caribbean as well as tropical Africa. This paper, which focuses on the plants of the Old World tropics that became established with slavery in the Caribbean, seeks to illuminate the botanical legacy of Africans in the circum-Caribbean region. Key words: African diaspora, Caribbean, ethnobotany, slaves, plant introductions. RESUME.—La diaspora africaine aux Ameriques ne s'est pas limitee aux person- nes, elle a egalement affecte les plantes. Les traiteurs d'esclaves ajoutaient a leur cargaison humaine des plantes exploitables dAfrique et du vieux monde pour les faire cultiver dans leurs jardins par les esclaves ou les marrons libres. En outre les Africains connaissaient beaucoup de plantes dAsie grace a de precedents echanges de cultures avec le sous-continent indien. -

Section 3 2018 Edition

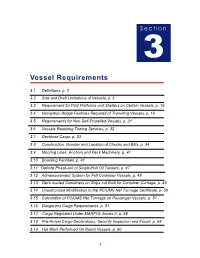

S e c ti o n 3 Vessel Requirements 3.1 Definitions, p. 2 3.2 Size and Draft Limitations of Vessels, p. 4 3.3 Requirement for Pilot Platforms and Shelters on Certain Vessels, p. 16 3.4 Navigation Bridge Features Required of Transiting Vessels, p. 19 3.5 Requirements for Non-Self-Propelled Vessels, p. 31 3.6 Vessels Requiring Towing Services, p. 32 3.7 Deckload Cargo, p. 33 3.8 Construction, Number and Location of Chocks and Bitts, p. 34 3.9 Mooring Lines, Anchors and Deck Machinery, p. 41 3.10 Boarding Facilities, p. 41 3.11 Definite Phase-out of Single-Hull Oil Tankers, p. 47 3.12 Admeasurement System for Full Container Vessels, p. 48 3.13 Deck-loaded Containers on Ships not Built for Container Carriage, p. 49 3.14 Unauthorized Modification to the PC/UMS Net Tonnage Certificate, p. 50 3.15 Calculation of PC/UMS Net Tonnage on Passenger Vessels, p. 51 3.16 Dangerous Cargo Requirements, p. 51 3.17 Cargo Regulated Under MARPOL Annex II, p. 58 3.18 Pre-Arrival Cargo Declarations, Security Inspection and Escort, p. 58 3.19 Hot Work Performed On Board Vessels, p. 60 1 OP Operations Manual Section 3 2018 Edition 3.20 Manning Requirements, p. 61 3.21 Additional Pilots Due to Vessel Deficiencies, p. 62 3.22 Pilot Accommodations Aboard Transiting Vessels, p. 63 3.23 Main Source of Electric Power, p. 63 3.24 Emergency Source of Electrical Power, p. 63 3.25 Sanitary Facilities and Sewage Handling, p. -

Prospects for Regional Cooperation Between Latin America and the Caribbean Region and the Asia and Pacific Region: Perspective from East Asia

ADBI Working Paper Series Prospects for Regional Cooperation between Latin America and the Caribbean Region and the Asia and Pacific Region: Perspective from East Asia Erlinda M. Medalla and Jenny D. Balboa No. 217 May 2010 Asian Development Bank Institute Erlinda M. Medalla is a senior research fellow at the Philippine Institute for Development Studies in Makati, Philippines. Jenny D. Balboa is a research associate at the Philippine Institute for Development Studies. The authors acknowledge the excellent research assistance of Melalyn Mantaring, Susan Pizaro, and Mildred Belizario. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, the Asian Development Bank (ADB), its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. ADBI encourages readers to post their comments on the main page for each working paper (given in the citation below). Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Medalla, E. M., and J. D. Balboa. 2010. Prospects for Regional Cooperation between Latin America and the Caribbean Region and the Asia and Pacific Region: Perspective from East Asia. ADBI Working Paper 217. -

Glossary of Port Industry Terminology

Glossary of Port Industry Terminology Berth: 1) The area allotted to accommodate a vessel alongside a wharf, or the area in which a vessel swings when at anchor. 2) Or in “cruise terminology ” a bed. Berthage: A tariff charged to a vessel occupying a berth. It is calculated by applying the current tariff rate per GT for each of the first 2 twelve-hour periods. Each additional hour is charged at a lower published rate per GT. Bollard: Is a short vertical post used on a ship or a quay, principally for mooring. Breakbulk: Non-containerized general cargo. Examples include iron, steel, machinery, linerboard, woodpulp and yachts. Cabin: A passenger room onboard the cruise ship – sometimes called a stateroom or a berth. CBSA: Canada Border Services Agency (occasionally referred to as Canada Customs). Coastal Trading Act: An Act respecting the use of foreign ships and non-duty paid ships in the coasting trade. (Canadian version of American “Jones Act” see cabotage below). Cabotage Water transportation term applicable to shipments between ports of a nation; commonly refers to coastwise or intercoastal navigation or trade. Many nations, including the United States, have cabotage laws which require national flag vessels to provide domestic interport service. (In US this is referred to as the “Jones Act”). Chart Datum: A plan below which the tide will seldom fall. The Canadian Hydrographic Service has adopted the plane of Lowest Normal Tides (LNT) as chart datum. To find the depth of water, the height of tide must be added to the depth shown on the chart. Tidal heights preceded by a (-) must be subtracted from the charted depth. -

Review of Maritime Transport 2020 37

2 The present chapter focuses on key developments related to the supply of maritime transport during this past year. It also assesses the early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the supply of maritime transport services and industries and discusses the responses, lessons learned and possible implications of the pandemic in terms of forces shaping supply and the industry’s long-term goal of decarbonization. The pandemic has had a significant impact on the shipping industry. On the one hand, lockdowns and factory closures gradually affected demand for maritime transport, due to reduced cargo volumes (see chapter 1). On the other hand, safety measures applied to contain the spread of the virus, such as lockdowns and travel restrictions, affected the movement of maritime transport workers and procedural changes introduced in ports, and induced operational disruptions in the supply of maritime transport. These prompted changes in shipping operations and requests for government support in the sector. They made the industry reflect on ways to enhance resilience of the sector to future shocks. This chapter reviews world fleet developments such as MARITIME annual fleet growth, changes to the structure and age of the fleet. It considers selected segments of the maritime TRANSPORT supply chain, such as shipbuilding, ship recycling, ship ownership, ship registration and the maritime workforce, SERVICES AND emphasizing the impacts of the pandemic on maritime INFRASTRUCTURE transport and marine manufacturing industries and on the supply of shipping services. SUPPLY It also examines the impact of the pandemic on the container, dry bulk and tanker freight markets; government responses to support shipping; and industry prospects, in particular with regard to accelerated digitalization and the prioritization of environmental sustainability. -

Hyundai Merchant Marine’ Rebrands As ‘HMM’ 2020-03-31

March 2021 HMM Co.,Ltd. HMM Service Promotion Material Table of Contents I. About HMM 1. Company Overview - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4 2. Financial Status - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 6 3. Expansion Plan & Sustainability - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 7 4. HMM News - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 13 5. Container Solutions - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 25 II. Market Outlook 1. Supply & Demand - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 41 2. Market Issue - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 47 HMM Co.,Ltd. 2 Contents I. About HMM 1. Company Overview - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4 2. Financial Status - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 6 3. Expansion Plan & Sustainability - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 7 4. HMM News - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 13 5. Container Solutions - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 25 II. Market Outlook HMM Co.,Ltd. 3 I -1. Company Overview The Bridge To Your Dream …… Since its humble beginning with just three VLCCs in 1976, HMM has developed over the years, overcoming numerous crises, to become a leading light in the Korean maritime industry. HMM is now a world-renowned integrated logistics company, operating around 120 state-of-the-art-vessels, and broad range -

Aaa800ews0p1260outi0june0

Report No. AAA80 - DJ Republic of Djibouti Public Disclosure Authorized Study on regulation of private operators in the port of Djibouti Technical Assistance Final report June 2012 Middle East and North Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized Transport Group World Bank document Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Study on regulation of private operators in the port of Djibouti Contents CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 8 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 9 REGULATION ACTION PLAN FOR PORT ACTIVITES IN DJIBOUTI ........................................ 13 REPORT 1 - DIAGNOSIS ................................................................................................................. 16 1. PORT FACILITIES AND OPERATORS ................................................................................. 17 1.1. An outstanding port and logistics hub .......................................................... 17 1.2. Doraleh oil terminal ...................................................................................... 18 1.3. Doraleh container terminal ........................................................................... 18 1.4. Djibouti container terminal ........................................................................... 19 1.5. Djibouti bulk terminal .................................................................................. -

ONI-54-A.Pdf

r~us U. S. FLEET TRAIN- Division cf Naval Intelligence-Identification and Characteristics Section e AD Destroyer Tenders Page AP Troop Transports Pa g e t Wo "'W" i "~ p. 4-5 z MELVILLE 28 5 BURROWS 14 3, 4 DOBBIN Class 4 7 WHARTON 9 9 BLACK HAWK 28 21, 22 WAKEFIELD Class 12 11, 12 ALTAIR Class 28 23 WEST POINT 13 14, 15, 17-19 DIXIE Class 7 24 ORIZABA 13 16 CASCADE 10 29 U. S. GRANT 14 20,21 HAMUL Class 22 31, 3Z CHATEAU THIERRY Class 9 33 REPUBLIC 14 AS Submarine Tenders 41 STRATFORD 14 3 HOLLAND 5 54, 61 HERMIT AGE Class 13 5 BEAVER 16 63 ROCHAMBEAU 12 11, 12, 15 19 FULTON Class 7 67 DOROTHEA L. DIX 25 Sin a ll p. H 13, 14 GRIFFIN Class 22 69- 71,76 ELIZ . STANTON Cla ss 23 20 OTUS 26 72 SUSAN B. ANTHONY 15 21 AN TEA US 16 75 GEMINI 17 77 THURSTON 20 AR Repair Ships 110- "GENERAL" Class 10 1 MEDUSA 5 W orld W ar I types p. 9 3, 4 PROMETHEUS Class 28 APA Attack Transports 5- VULCAN Class 7 1, 11 DOYEN Class 30 e 9, 12 DELTA Class 22 2, 3, 12, 14- 17 HARRIS Class 9 10 ALCOR 14 4, 5 McCAWLEY , BARNETT 15 11 RIGEL 28 6-9 HEYWOOD Class 15 ARH Hull Repair Ships 10, 23 HARRY LEE Class 14 Maritime types p. 10-11 13 J T. DICKMAN 9 1 JASON 7 18-zo; 29, 30 PRESIDENT Class 10 21, 28, 31, 32 CRESCENT CITY Class 11 . -

U.S. Government Printing Office Style Manual, 2008

U.S. Government Printing Offi ce Style Manual An official guide to the form and style of Federal Government printing 2008 PPreliminary-CD.inddreliminary-CD.indd i 33/4/09/4/09 110:18:040:18:04 AAMM Production and Distribution Notes Th is publication was typeset electronically using Helvetica and Minion Pro typefaces. It was printed using vegetable oil-based ink on recycled paper containing 30% post consumer waste. Th e GPO Style Manual will be distributed to libraries in the Federal Depository Library Program. To fi nd a depository library near you, please go to the Federal depository library directory at http://catalog.gpo.gov/fdlpdir/public.jsp. Th e electronic text of this publication is available for public use free of charge at http://www.gpoaccess.gov/stylemanual/index.html. Use of ISBN Prefi x Th is is the offi cial U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identifi ed to certify its authenticity. ISBN 978–0–16–081813–4 is for U.S. Government Printing Offi ce offi cial editions only. Th e Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Printing Offi ce requests that any re- printed edition be labeled clearly as a copy of the authentic work, and that a new ISBN be assigned. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 ISBN 978-0-16-081813-4 (CD) II PPreliminary-CD.inddreliminary-CD.indd iiii 33/4/09/4/09 110:18:050:18:05 AAMM THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE STYLE MANUAL IS PUBLISHED UNDER THE DIRECTION AND AUTHORITY OF THE PUBLIC PRINTER OF THE UNITED STATES Robert C. -

Inside the Volcano – a Curriculum on Nicaragua

Inside the Volcano: A Curriculum on Nicaragua Edited by William Bigelow and Jeff Edmundson Network of Educators on the Americas (NECA) P.O. Box 73038 Washington, DC 20056-3038 Network of Educators' Committees on Central America Washington, D.C. About the readings: We are grateful to the Institute for Food and Development Policy for permission to reproduce Imagine You Were A Nicaraguan (from Nicaragua: What Difference Could A Revolution Make?), Nicaragua: Give Change a Chance, The Plastic Kid (from Now We Can Speak) and Gringos and Contras on Our Land (from Don’t Be Afraid, Gringo). Excerpt from Nicaragua: The People Speak © 1985 Bergin and Garvey printed with permission from Greenwood Press. About the artwork: The pictures by Rini Templeton (pages 12, 24, 26, 29, 30, 31, 38, 57 60, 61, 66, 74, 75, 86, 87 90, 91. 101, 112, and the cover) are used with the cooperation of the Rini Templeton Memorial Fund and can be found in the beautiful, bilingual collection of over 500 illustrations entitled El Arte de Rini Templeton: Donde hay vida y lucha - The Art of Rini Templeton: Where there is life and struggle, 1989, WA: The Real Comet Press. See Appendix A for ordering information. The drawing on page 15 is by Nicaraguan artist Donald Navas. The Nicaraguan Cultural Alliance has the original pen and ink and others for sale. See Appendix A for address. The illustrations on pages 31, 32 and 52 are by Nicaraguan artist Leonicio Saenz. An artist of considerable acclaim in Central America, Saenz is a frequent contributor to Nicar&uac, a monthly publication of the Nicaraguan Ministry of Culture. -

Transformations in Port-Cities in Times of Globalisation: the Case of the Rio De La Plata Estuary

Transformations in Port-Cities in Times of Globalisation: The Case of the Rio de la Plata Estuary. Maria J. Bazan-Lopes. DUT – Delft University of Technology The role of Ports under globalisation Since 1960s, the port/city relationship has been influenced by external and internal factors, particularly the changes to world transport systems, the revolution in shipping industry and the design of port infrastructure. The traditional role of ports in transport and stocking, loading and unloading, has changed in order to link specialised activities and services inside the port-areas, including industrial, business, commercial, environmental, administrative and logistic services. As globalisation deepens and expands, ports are increasingly becoming the new dynamic knots between the international production and the global distribution networks, and the cores of regional development. The concept of port as a logistic place implies a new port-city relationship, in which the port- functions are not restricted to the port-area but to the whole transport and distribution chain giving more added value to the city (Aldoney Vargas, 1997). The main issues that ports face presently can be summarised as follows (Alemany Llovera, 1997): · To modernise the entire port-structure in terms of organisation, management, equipment and services with new requirements in the “cost-efficiency-quality” relationship. This implies an increasing demand on water and land space, and the consequent reduction of directly related employment; · To offer an economically and