Mammals on the Margin: Documenting Recent Changes to Large Mammal Distributions in a Densely Populated Biodiversity Hotspot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keshav Ravi by Keshav Ravi

by Keshav Ravi by Keshav Ravi Preface About the Author In the whole world, there are more than 30,000 species Keshav Ravi is a caring and compassionate third grader threatened with extinction today. One prominent way to who has been fascinated by nature throughout his raise awareness as to the plight of these animals is, of childhood. Keshav is a prolific reader and writer of course, education. nonfiction and is always eager to share what he has learned with others. I have always been interested in wildlife, from extinct dinosaurs to the lemurs of Madagascar. At my ninth Outside of his family, Keshav is thrilled to have birthday, one personal writing project I had going was on the support of invested animal advocates, such as endangered wildlife, and I had chosen to focus on India, Carole Hyde and Leonor Delgado, at the Palo Alto the country where I had spent a few summers, away from Humane Society. my home in California. Keshav also wishes to thank Ernest P. Walker’s Just as I began to explore the International Union for encyclopedia (Walker et al. 1975) Mammals of the World Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List species for for inspiration and the many Indian wildlife scientists India, I realized quickly that the severity of threat to a and photographers whose efforts have made this variety of species was immense. It was humbling to then work possible. realize that I would have to narrow my focus further down to a subset of species—and that brought me to this book on the Endangered Mammals of India. -

Nilgiris District, Tamil Nadu Connie Smith Tamil Nadu Overview

Nilgiris District, Tamil Nadu Connie Smith Tamil Nadu Overview Tamil Nadu is bordered by Pondicherry, Kerala, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. Sri Lanka, which has a significant Tamil minority, lies off the southeast coast. Tamil Nadu, with its traceable history of continuous human habitation since pre-historic times has cultural traditions amongst the oldest in the world. Colonised by the East India Company, Tamil Nadu was eventually incorporated into the Madras Presidency. After the independence of India, the state of Tamil Nadu was created in 1969 based on linguistic boundaries. The politics of Tamil Nadu has been dominated by DMK and AIADMK, which are the products of the Dravidian movement that demanded concessions for the 'Dravidian' population of Tamil Nadu. Lying on a low plain along the southeastern coast of the Indian peninsula, Tamil Nadu is bounded by the Eastern Ghats in the north and Nilgiri, Anai Malai hills and Palakkad (Palghat Gap) on the west. The state has large fertile areas along the Coromandel coast, the Palk strait, and the Gulf of Mannar. The fertile plains of Tamil Nadu are fed by rivers such as Kaveri, Palar and Vaigai and by the northeast monsoon. Traditionally an agricultural state, Tamil Nadu is a leading producer of agricultural products. Tribal Population As per 2001 census, out of the total state population of 62,405,679, the population of Scheduled Castes is 11,857,504 and that of Scheduled Tribes is 651,321. This constitutes 19% and 1.04% of the total population respectively.1 Further, the literacy level of the Adi Dravidar is only 63.19% and that of Tribal is 41.53%. -

Terminalia L

KFRI Research Report No. 515 ISSN 0970-8103 Seed ecological and regeneration studies on keystone tree species of the evergreen and moist deciduous forest ecosystems (Final Report of Project No. KFRI RP 627.3/2011) P.K. Chandrasekhara Pillai V.B. Sreekumar K.A. Sreejith G.E. Mallikarjunaswami Kerala Forest Research Institute (An Institution of Kerala State Council for Science, Technology and Environment) Peechi 680 653, Thrissur, Kerala, India June 2016 PROJECT PARTICULARS Project No. : KFRI RP 627.3/2011 Title : Seed ecological and regeneration studies on keystone tree species of the evergreen and moist deciduous forest ecosystems Principal Investigator : Dr. P. K. Chandrasekhara Pillai Associate Investigators : Dr. V. B. Sreekumar Dr. K. A. Sreejith Dr. G. E. Mallikarjunaswami Research Fellow : Mrs. M. M. Sowmya (2011-12) Miss. M. R. Sruthi (2012-14) Objectives : To assess seed ecology and regeneration status of major keystone tree species in the permanent plots Duration : August 2011 - March 2014 Funding Agency : KFRI Plan Grant i CONTENTS Acknowledgements …………………………………………………iii Abstract ……………………………………………………………..iv 1. Introduction ……………………………………………………… 1 2. Materials and Methods …………………………………………....3 3. Results and Discussion ………………………………………........7 3.1. Study sites in evergreen forests ………………………………. 8 3.2. Study sites in moist deciduous forests ………………………. 15 3.3. Study sites in shola forests …………………………………... 17 4. Conclusions ……………………………………………………... 19 5. References ………………………………………………………. 20 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The study was made possible by the financial assistance from Kerala Forest Research Institutes Plan Grant. We express our deep sense of gratitude and thanks to the KFRI for awarding the grant. We extend sincere thanks to the officials of the Kerala Forest Department for providing necessary permissions and support to carry out the study. -

Western Ghats & Sri Lanka Biodiversity Hotspot

Ecosystem Profile WESTERN GHATS & SRI LANKA BIODIVERSITY HOTSPOT WESTERN GHATS REGION FINAL VERSION MAY 2007 Prepared by: Kamal S. Bawa, Arundhati Das and Jagdish Krishnaswamy (Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology & the Environment - ATREE) K. Ullas Karanth, N. Samba Kumar and Madhu Rao (Wildlife Conservation Society) in collaboration with: Praveen Bhargav, Wildlife First K.N. Ganeshaiah, University of Agricultural Sciences Srinivas V., Foundation for Ecological Research, Advocacy and Learning incorporating contributions from: Narayani Barve, ATREE Sham Davande, ATREE Balanchandra Hegde, Sahyadri Wildlife and Forest Conservation Trust N.M. Ishwar, Wildlife Institute of India Zafar-ul Islam, Indian Bird Conservation Network Niren Jain, Kudremukh Wildlife Foundation Jayant Kulkarni, Envirosearch S. Lele, Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Environment & Development M.D. Madhusudan, Nature Conservation Foundation Nandita Mahadev, University of Agricultural Sciences Kiran M.C., ATREE Prachi Mehta, Envirosearch Divya Mudappa, Nature Conservation Foundation Seema Purshothaman, ATREE Roopali Raghavan, ATREE T. R. Shankar Raman, Nature Conservation Foundation Sharmishta Sarkar, ATREE Mohammed Irfan Ullah, ATREE and with the technical support of: Conservation International-Center for Applied Biodiversity Science Assisted by the following experts and contributors: Rauf Ali Gladwin Joseph Uma Shaanker Rene Borges R. Kannan B. Siddharthan Jake Brunner Ajith Kumar C.S. Silori ii Milind Bunyan M.S.R. Murthy Mewa Singh Ravi Chellam Venkat Narayana H. Sudarshan B.A. Daniel T.S. Nayar R. Sukumar Ranjit Daniels Rohan Pethiyagoda R. Vasudeva Soubadra Devy Narendra Prasad K. Vasudevan P. Dharma Rajan M.K. Prasad Muthu Velautham P.S. Easa Asad Rahmani Arun Venkatraman Madhav Gadgil S.N. Rai Siddharth Yadav T. Ganesh Pratim Roy Santosh George P.S. -

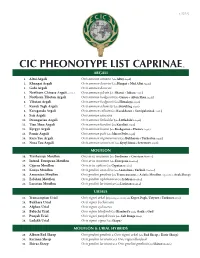

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

Edge Transition Impacts on Swamp Plant Communities in the Nilgiri Mountains, Southern India - 909

Mohandass et al.: Edge transition impacts on swamp plant communities in the Nilgiri Mountains, Southern India - 909 - EDGE TRANSITION IMPACTS ON SWAMP PLANT COMMUNITIES IN THE NILGIRI MOUNTAINS, SOUTHERN INDIA MOHANDASS, D.1* ̶ PUYRAVAUD, J-P2 ̶ HUGHES, A. C.3 ̶ DAVIDAR, P.4 ̶ GANESH, P. S.5 ̶ CAMPBELL, M.6 1Key laboratory of Tropical Forest Ecology, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden (XTBG), Chinese Academy of Sciences, Menglun, Mengla County, Yunnan – 666 303, P.R. China 2ECOS, 9A Frédéric Ozanam Street, Colas Nagar, Puducherry 605001, India 3Centre for Integrative Conservation, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden (XTBG), Chinese Academy of Sciences, Menglun, Mengla County, Yunnan- 666303, P.R. China. 4Department of Ecology and Environmental Sciences, Pondicherry University, Kalapet, Puducherry -605014, India 5Department of Biological Sciences, Birla Institute of Technology & Science, BITS, Pilani - Hyderabad Campus, India 6Centre for Tropical Environmental and Sustainability Science (T.E.S.S), School of Marine and Tropical Biology, James Cook University, Cairns, Queensland, Australia *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] (Received 14th Nov 2012; accepted 22nd June 2014) Abstract. Swamps represent a relatively understudied ecosystem in many regions, which contrasts markedly with the research attention which other wetlands and Mangrove ecosystems have received. In the upper Nilgiris of southern India, montane swamps are restricted to geographic areas with flat surfaces and bounded by different edge transition vegetation types including grasslands and shola forests. Our study examined whether species richness, endemism, edge and the composition of swamp interior communities have a significant relationship with swamp area. Using species-area curves we continued sampling for species in each swamp until species richness reached the asympote within that swamp. -

Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve

Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve April 6, 2021 About Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve The Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve was the first biosphere reserve in India established in the year 1986. It is located in the Western Ghats and includes 2 of the 10 biogeographical provinces of India. The total area of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve is 5,520 sq. km. It is located in the Western Ghats between 76°- 77°15‘E and 11°15‘ – 12°15‘N. The annual rainfall of the reserve ranges from 500 mm to 7000 mm with temperature ranging from 0°C during winter to 41°C during summer. The Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve encompasses parts of Tamilnadu, Kerala and Karnataka. The Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve falls under the biogeographic region of the Malabar rain forest. The Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary, Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary Bandipur National Park, Nagarhole National Park, Mukurthi National Park and Silent Valley are the protected areas present within this reserve. Vegetational Types of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve Nature of S.No Forest type Area of occurrence Vegetation Dense, moist and In the narrow Moist multi storeyed 1 valleys of Silent evergreen forest with Valley gigantic trees Nilambur and Palghat 2 Semi evergreen Moist, deciduous division North east part of 3 Thorn Dense the Nilgiri district Savannah Trees scattered Mudumalai and 4 woodland amid woodland Bandipur South and western High elevated Sholas & catchment area, 5 evergreen with grasslands Mukurthi national grasslands park Flora About 3,300 species of flowering plants can be seen out of species 132 are endemic to the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. The genus Baeolepis is exclusively endemic to the Nilgiris. -

Assessment of Liverwort and Hornwort Flora of Nilgiri Hills, Western Ghats (India)

Polish Botanical Journal 58(2): 525–537, 2013 DOI: 10.2478/pbj-2013-0038 ASSESSMENT OF LIVERWORT AND HORNWORT FLORA OF NILGIRI HILLS, WESTERN GHATS (INDIA) PR AV E E N KUMAR VERMA 1, AFROZ ALAM & K. K. RAWAT Abstract. Bryophytes are an important part of the flora of the Nilgiri Hills of Western Ghats, a biodiversity hotspot. This paper gives an updated catalogue of the Hepaticae of the Nilgiri Hills. The list includes all available records, based on the authors’ collections and those in LWU and other renowned herbaria. The catalogue of liverworts indicates their substrate and occur- rence, and includes several records new for the Nilgiri bryoflora as well as for Western Ghats. The list of Hepaticae contains 29 families, 55 genera and 164 taxa. The list of Anthocerotae comprises 2 families, 3 genera and 5 taxa belonging to almost all life form types. Key words: Western Ghats, biodiversity hotspot, Tamil Nadu, Bryophyta, Hepaticae, Anthocerotae Praveen Kumar Verma, Rain Forest Research Institute, Deovan, Sotai Ali, Post Box # 136, Jorhat – 785 001 (Assam), India; e-mail: [email protected] Afroz Alam, Department of Bioscience and Biotechnology, Banasthali University, Tonk – 304 022 (Rajasthan), India; e-mail: [email protected] K. K. Rawat, CSIR-National Botanical Research Institute, Rana Pratap Marg, Lucknow – 226 001, India; e-mail: drkkrawat@ rediffmail.com INTRODUCT I ON The Nilgiri Hills of Tamil Nadu are a part of the tropical hill forest, montane wet temperate forests, Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve (NBR), recognized mixed deciduous, montane evergreen (shola grass- under the Man and Biosphere (MAB) Program land) (see also Champion & Seth 1968; Hockings of UNESCO. -

Chec List Distribution and Composition of Butterfly Species Along The

Check List 8(6): 1196–1215, 2012 © 2012 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution PECIES S OF Distribution and composition of butterfly species along ISTS L the latitudinal and habitat gradients of the Western Ghats 1 * 2 of India 3 Anand Padhye , Sheetal Shelke and Neelesh Dahanukar 1 Abasaheb Garware College, Department of Zoology. Karve Road, Pune 411004, India. 2 Abasaheb Garware College, [email protected] of Biodiversity. Karve Road, Pune 411004, India. 3 Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Sai Trinity Building, Sus Road, Pashan, Pune 411021, India. * Corresponding author. Email: Abstract: Distribution of butterfly species along the latitudinal and habitat gradients of the Western Ghats was studied. The Western Ghats was divided into 14 latitude zones and the species diversity in each latitude zone, along with habitats of their occurrence, were studied using the data from literature survey for the entire Western Ghats as well as data from personal observations in the areas between 14°N to 20°N latitudes. Out of 334 species recorded from the Western Ghats, 58 species were found in all latitudinal zones, while 5 species were reported in only one latitudinal zone. Further, southern Western Ghats consisted of more number of species and more number of genera as compared to northern Western Ghats. Latitudinal zones between 10°N to 12°N had most of the Western Ghats endemic species. Habitat wise distribution of species revealed three significant clusters grossly separated by the level of human disturbance. Evergreen forest habitats supported maximum number of species endemic to the Western Ghats. -

Forest and Wildlife F I L D L I

2 e Forest and Wildlife f i l d l i 2.1 Introduction Forest plays a vital role in safeguarding the W d amil Nadu is the southern most state of India. The environment and contributes much to economic n a t total geographical area of Tamil Nadu is 1,30,058 development. Forests are generally considered s e r sq.kms, of which the recorded forest area is environmental capital in that it directly relates to the o T F 22,877 sq.kms, which constitute 17.59% of the States environment. Conservation and preservation of forest is a geographical area2. The forest area of the State is classified as pre-requisite for maintaining a healthy eco-system. Besides Reserved Forest, Reserved land and Unclassified forest. ensuring ecological stability, forest provides employment Reserved Forests (RF) covers about 19,388 sq.km (85%), opportunities to rural and tribal folk and provides wood and Protected Forests (PF) covers about 2,183 sq.km (9.6%) and minor forest products like honey, herbs, fruits, berries and Unclassified Forest (UF) covers an area of about 1,306 sq.km materials for domestic use.3 (5.8%)3 2.2 Forest area Physiographically the salient features of the land are the coastal plains along the east coast with a land coverage of The State of Forest Report 2003, of Forest Survey of 17,150 sq.kms (approx) and Western Ghats, a continuous India shows the recorded forest area of the state as mass of composite hill ranges of high elevation along the 22,877 sq.km in extent which is 17.59% of the geographical west, extending to an area of 44,401 sq.kms (approx). -

Table of Contents

NATIONAL BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN Western Ghats Ecoregion R. J. Ranjit Daniels Coordinator Hon. Secretary Chennai Snake Park Trust Raj Bhavan PO Chennai 600 022 & Director Care Earth No 5, Shrinivas 21st Street Thillaiganganagar Chennai 600 061 Executing Agency: Government of India – Ministry of Environment and Forests Funding Agency: United Nations Development Programme/Global Environment Facility Technical Implementing Agency: Technical and Policy Core Group coordinated by Kalpavriksh Administrative Agency: Biotech Consortium India Limited Acknowledgements This document has been prepared as part of the national programme titled 'National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan' (NBSAP) – India, funded by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and Global Environment Facility (GEF). The support and cooperation extended by the Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India (NBSAP-Executing agency), the Technical and Policy Core Group (NBSAP- Technical implementing agency Coordinated by Kalpavriksh) and the Biotech Consortium India Ltd (NBSAP-Administrative agency) are most gratefully acknowledged herein. The support and encouragement provided by Shri B Vijayaraghavan IAS (Retd) – Chairman of the Chennai Snake Park Trust is also gratefully acknowledged. Throughout the process of preparation of the document a number of institutions/people helped in various ways. The complete list of institutions/persons who interacted/participated in the discussion meetings and contributed to the document is provided elsewhere. The following colleagues most willingly extended their support in organising discussion meetings and in channelising information and feedback that went into preparation of the document. Dr Jayshree Vencatesan *– Joint Director, Care Earth, Chennai. Shri Utkarsh Ghate *– RANWA, Pune. Dr P T Cherian* - Additional Director and Officer-in-Charge, ZSI, Chennai. -

Food Habits of the Indian Giant Flying Squirrel (Petaurista Philippensis) in a Rain Forest Fragment, Western Ghats

Journal of Mammalogy, 89(6):1550–1556, 2008 FOOD HABITS OF THE INDIAN GIANT FLYING SQUIRREL (PETAURISTA PHILIPPENSIS) IN A RAIN FOREST FRAGMENT, WESTERN GHATS R. NANDINI* AND N. PARTHASARATHY Department of Ecology and Environmental Sciences, Pondicherry University, Puducherry, 605 014, India Present address of RN: National Institute of Advanced Studies, Indian Institute of Science campus, Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article/89/6/1550/911817 by guest on 28 September 2021 Bangalore, 560 012, India Present address of RN: Department of Biological Sciences, Auburn University, Auburn, AL 36849, USA We examined the feeding habits of the Indian giant flying squirrel (Petaurista philippensis) in a rain-forest fragment in southern Western Ghats, India, from December 1999 to March 2000. Flying squirrels consumed 4 major plant parts belonging to 9 plant species. Ficus racemosa was the most-eaten species (68.1%) during the period of the study, followed by Cullenia exarillata (9.57%) and Artocarpus heterophyllus (6.38%). The most commonly consumed food item was the fruit of F. racemosa (48.93%). Leaves formed an important component of the diet (32.97%) and the leaves of F. racemosa were consumed more than those of any other species. Flying squirrels proved to be tolerant of disturbance and exploited food resources at the fragment edge, including exotic planted species. Key words: edge, Ficus, fig fruits, folivore, Petaurista philippensis, rain-forest fragment, Western Ghats The adaptability of mammals allows them to exist in varied across the Western Ghats seem to increase with disturbance. environments and helps them to cope with habitat fragmenta- Ashraf et al.