Brunelleschi's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovering Florence in the Footsteps of Dante Alighieri: “Must-Sees”

1 JUNE 2021 MICHELLE 324 DISCOVERING FLORENCE IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF DANTE ALIGHIERI: “MUST-SEES” In 1265, one of the greatest poets of all time was born in Florence, Italy. Dante Alighieri has an incomparable legacy… After Dante, no other poet has ever reached the same level of respect, recognition, and fame. Not only did he transform the Italian language, but he also forever altered European literature. Among his works, “Divine Comedy,” is the most famous epic poem, continuing to inspire readers and writers to this day. So, how did Dante Alighieri become the father of the Italian language? Well, Dante’s writing was different from other prose at the time. Dante used “common” vernacular in his poetry, making it more simple for common people to understand. Moreover, Dante was deeply in love. When he was only nine years old, Dante experienced love at first sight, when he saw a young woman named “Beatrice.” His passion, devotion, and search for Beatrice formed a language understood by all - love. For centuries, Dante’s romanticism has not only lasted, but also grown. For those interested in discovering more about the mysteries of Dante Alighieri and his life in Florence , there are a handful of places you can visit. As you walk through the same streets Dante once walked, imagine the emotion he felt in his everlasting search of Beatrice. Put yourself in his shoes, as you explore the life of Dante in Florence, Italy. Consider visiting the following places: Casa di Dante Where it all began… Dante’s childhood home. Located right in the center of Florence, you can find the location of Dante’s birth and where he spent many years growing up. -

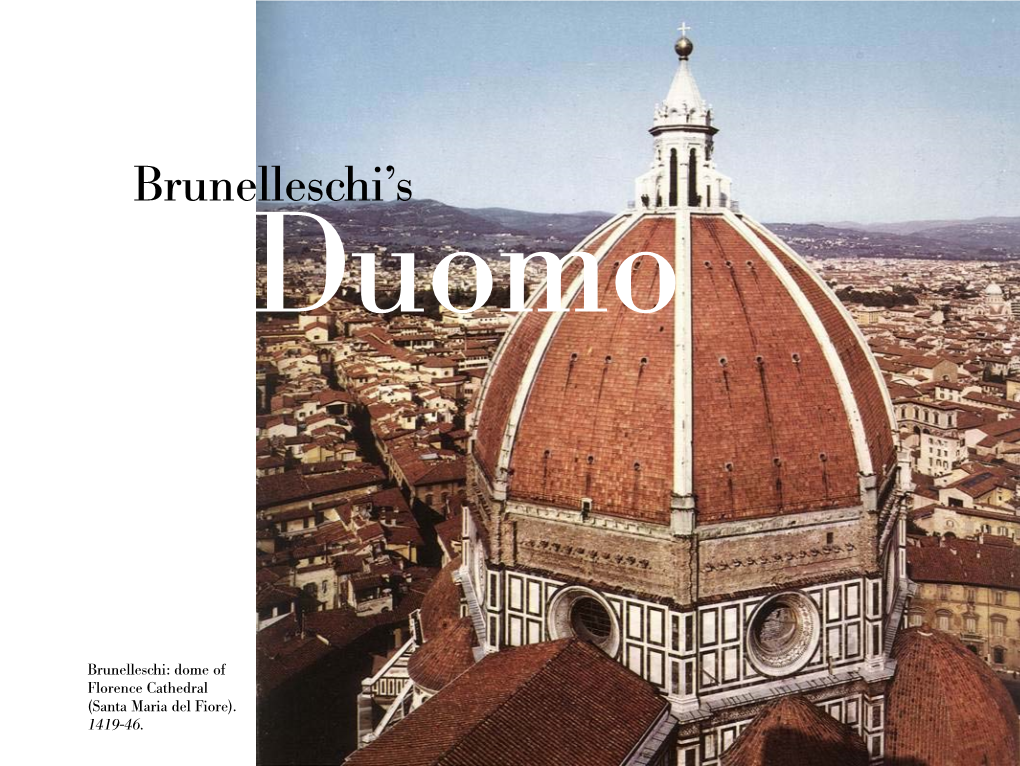

Stepping out of Brunelleschi's Shadow

STEPPING OUT OF BRUNELLESCHI’S SHADOW. THE CONSECRATION OF SANTA MARIA DEL FIORE AS INTERNATIONAL STATECRAFT IN MEDICEAN FLORENCE Roger J. Crum In his De pictura of 1435 (translated by the author into Italian as Della pittura in 1436) Leon Battista Alberti praised Brunelleschi’s dome of Florence cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore [Fig. 1], as ‘such a large struc- ture’ that it rose ‘above the skies, ample to cover with its shadow all the Tuscan people’.1 Alberti was writing metaphorically, but he might as easily have written literally in prediction of the shadowing effect that Brunelleschi’s dome, dedicated on 30 August 1436, would eventually cast over the Florentine cultural and historical landscape of the next several centuries.2 So ever-present has Brunelleschi’s structure been in the historical perspective of scholars – not to mention in the more popular conception of Florence – that its stately coming into being in the Quattrocento has almost fully overshadowed in memory and sense of importance another significant moment in the history of the cathedral and city of Florence that immediately preceded the dome’s dedication in 1436: the consecration of Santa Maria del Fiore itself on 25 March of that same year.3 The cathedral was consecrated by Pope Eugenius IV (r. 1431–1447), and the ceremony witnessed the unification in purpose of high eccle- siastical, foreign, and Florentine dignitaries. The event brought to a close a history that had begun 140 years earlier when the first stones of the church were laid in 1296; in 1436, the actual date of the con- secration was particularly auspicious, for not only is 25 March the feast of the Annunciation, but in the Renaissance that day was also the start of the Florentine calendar year. -

Prato and Montemurlo Tuscany That Points to the Future

Prato Area Prato and Montemurlo Tuscany that points to the future www.pratoturismo.it ENG Prato and Montemurlo Prato and Montemurlo one after discover treasures of the Etruscan the other, lying on a teeming and era, passing through the Middle busy plain, surrounded by moun- Ages and reaching the contempo- tains and hills in the heart of Tu- rary age. Their geographical posi- scany, united by a common destiny tion is strategic for visiting a large that has made them famous wor- part of Tuscany; a few kilometers ldwide for the production of pre- away you can find Unesco heritage cious and innovative fabrics, offer sites (the two Medici Villas of Pog- historical, artistic and landscape gio a Caiano and Artimino), pro- attractions of great importance. tected areas and cities of art among Going to these territories means the most famous in the world, such making a real journey through as Florence, Lucca, Pisa and Siena. time, through artistic itineraries to 2 3 Prato contemporary city between tradition and innovation PRATO CONTEMPORARY CITY BETWEEN TRADITION AND INNOVATION t is the second city in combination is in two highly repre- Tuscany and the third in sentative museums of the city: the central Italy for number Textile Museum and the Luigi Pec- of inhabitants, it is a ci Center for Contemporary Art. The contemporary city ca- city has written its history on the art pable of combining tradition and in- of reuse, wool regenerated from rags novation in a synthesis that is always has produced wealth, style, fashion; at the forefront, it is a real open-air the art of reuse has entered its DNA laboratory. -

"Nuper Rosarum Flores" and the Cathedral of Florence Author(S): Marvin Trachtenberg Source: Renaissance Quarterly, Vol

Architecture and Music Reunited: A New Reading of Dufay's "Nuper Rosarum Flores" and the Cathedral of Florence Author(s): Marvin Trachtenberg Source: Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 54, No. 3 (Autumn, 2001), pp. 740-775 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Renaissance Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1261923 . Accessed: 03/11/2014 00:42 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Renaissance Society of America are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Renaissance Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 192.147.172.89 on Mon, 3 Nov 2014 00:42:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Architectureand Alusic Reunited: .V A lVewReadi 0 u S uperRosarum Floresand theCathedral ofFlorence. byMARVIN TRACHTENBERG Theproportions of the voices are harmoniesforthe ears; those of the measure- mentsare harmoniesforthe eyes. Such harmoniesusuallyplease very much, withoutanyone knowing why, excepting the student of the causality of things. -Palladio O 567) Thechiasmatic themes ofarchitecture asfrozen mu-sic and mu-sicas singingthe architecture ofthe worldrun as leitmotifithrough the histories ofphilosophy, music, and architecture.Rarely, however,can historical intersections ofthese practices be identified. -

1 Santo Spirito in Florence: Brunelleschi, the Opera, the Quartiere and the Cantiere Submitted by Rocky Ruggiero to the Universi

Santo Spirito in Florence: Brunelleschi, the Opera, the Quartiere and the Cantiere Submitted by Rocky Ruggiero to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History and Visual Culture In March 2017. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature)…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Abstract The church of Santo Spirito in Florence is universally accepted as one of the architectural works of Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446). It is nevertheless surprising that contrary to such buildings as San Lorenzo or the Old Sacristy, the church has received relatively little scholarly attention. Most scholarship continues to rely upon the testimony of Brunelleschi’s earliest biographer, Antonio di Tuccio Manetti, to establish an administrative and artistic initiation date for the project in the middle of Brunelleschi’s career, around 1428. Through an exhaustive analysis of the biographer’s account, and subsequent comparison to the extant documentary evidence from the period, I have been able to establish that construction actually began at a considerably later date, around 1440. It is specifically during the two and half decades after Brunelleschi’s death in 1446 that very little is known about the proceedings of the project. A largely unpublished archival source which records the machinations of the Opera (works committee) of Santo Spirito from 1446-1461, sheds considerable light on the progress of construction during this period, as well as on the role of the Opera in the realization of the church. -

Insider's Florence

Insider’s Florence Explore the birthplace of the Renaissance November 8 - 15, 2014 Book Today! SmithsonianJourneys.org • 1.877.338.8687 Insider’s Florence Overview Florence is a wealth of Renaissance treasures, yet many of its riches elude all but the most experienced travelers. During this exclusive tour, Smithsonian Journey’s Resident Expert and popular art historian Elaine Ruffolo takes you behind the scenes to discover the city’s hidden gems. You’ll enjoy special access at some of Florence’s most celebrated sites during private after-hours visits and gain insight from local experts, curators, and museum directors. Learn about restoration issues with a conservator in the Uffizi’s lab, take tea with a principessa after a private viewing of her art collection, and meet with artisans practicing their ages-old art forms. During a special day in the countryside, you’ll also go behind the scenes to explore lovely villas and gardens once owned by members of the Medici family. Plus, enjoy time on your own to explore the city’s remarkable piazzas, restaurants, and other museums. This distinctive journey offers first time and returning visitors a chance to delve deeper into the arts and treasures of Florence. Smithsonian Expert Elaine Ruffolo November 8 - 15, 2014 For popular leader Elaine Ruffolo, Florence offers boundless opportunities to study and share the finest artistic achievements of the Renaissance. Having made her home in this splendid city, she serves as Resident Director for the Smithsonian’s popular Florence programs. She holds a Master’s degree in art history from Syracuse University and serves as a lecturer and field trip coordinator for the Syracuse University’s program in Italy. -

Chapter Eleven the Fourteenth Century

Chapter Eleven: The Fourteenth Century: A Time of Transition Calamity, Decay, and Violence: The Great Schism Boniface VIII vs. Philip the Fair of France Avignon Papacy / “Babylonian Captivity” 1378, three rival claimants to the papacy Church reform Peasant Revolt of 1381 – Robin Hood myth Calamity, Decay, and Violence: The Hundred Years’ War Conflict between France and England – Fought on French soil – Poitiers, Crécy, Agincourt Pillaging bands of mercenaries Introduction of the longbow 1 Calamity, Decay, and Violence: The Black Death 1348 Bubonic Plague Epidemic – Population decline Boccaccio’s Decameron – Eyewitness to the plague – Fabliaux, exempla, romances – “Human Comedy” vs. Divine Comedy Literature in the Fourteenth Century Dante’s Divine Comedy Influenced by intellectualism from Paris – Hierarchical, synthetic religious humanism Wide array of publications The Comedy of Dante Alighieri… – Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso – Organization – Terza Rima – Encyclopedic and complex 2 11.1 Enrico Pazzi, Dante Alighieri, 1865, Piazza Santa Croce, Florence Italy Symbolism in The Divine Comedy Journey – Virgil, Beatrice Numbers – Multiples of three, Trinity Punishments and Blessings Satan Light and Darkness – Intellectual estrangement from God 11.3 Domenico di Michelino, Dante and His Poem, 1465. Fresco, Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore (Duomo), Florence, Italy 3 Literature in Italy, England, and France: Petrarch (1304-1374) From Tuscany, South Florence Restless and curious – Collected and copied ancient texts Renaissance -

Scale Model of Florence Cathedral Dome

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 4 Issue 1 2013 Discovered: Scale Model of Florence Cathedral Dome Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation . "Discovered: Scale Model of Florence Cathedral Dome." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 4, 1 (2013). https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol4/iss1/21 This Discoveries is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. et al. ______________________________________________________________________________ DISCOVERIES Discovered: Scale Model of Florence Cathedral Dome Italian archaeologists have unearthed the remains of a mini dome near Florence’s cathedral — evidence, they say, that the structure served as a scale model for the majestic structure designed by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377- 1446). Found during excavations to expand the Cathedral museum, the model measures 9 feet in circumference and is made of bricks arranged in a herringbone pattern. “This building technique had been previously used in Persian domes, but Brunelleschi was the first to introduce it into Europe when he worked at the dome,” said Francesco Gurrieri, professor of Restoration of Monuments at the University of Florence. “Although at the moment we cannot confirm the small dome was the demonstration model for Brunelleschi’s plans, it did belong to the yard he created between 1420 and 1436, when he worked at one of the most incredible feats of engineering.” One of the most instantly recognizable churches in the world, the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore is the highest and widest (143 feet in diameter) masonry dome in the world. -

THE FLORENTINE HOUSE of MEDICI (1389-1743): POLITICS, PATRONAGE, and the USE of CULTURAL HERITAGE in SHAPING the RENAISSANCE by NICHOLAS J

THE FLORENTINE HOUSE OF MEDICI (1389-1743): POLITICS, PATRONAGE, AND THE USE OF CULTURAL HERITAGE IN SHAPING THE RENAISSANCE By NICHOLAS J. CUOZZO, MPP A thesis submitted to the Graduate School—New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Art History written under the direction of Archer St. Clair Harvey, Ph.D. and approved by _________________________ _________________________ _________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Florentine House of Medici (1389-1743): Politics, Patronage, and the Use of Cultural Heritage in Shaping the Renaissance By NICHOLAS J. CUOZZO, MPP Thesis Director: Archer St. Clair Harvey, Ph.D. A great many individuals and families of historical prominence contributed to the development of the Italian and larger European Renaissance through acts of patronage. Among them was the Florentine House of Medici. The Medici were an Italian noble house that served first as the de facto rulers of Florence, and then as Grand Dukes of Tuscany, from the mid-15th century to the mid-18th century. This thesis evaluates the contributions of eight consequential members of the Florentine Medici family, Cosimo di Giovanni, Lorenzo di Giovanni, Giovanni di Lorenzo, Cosimo I, Cosimo II, Cosimo III, Gian Gastone, and Anna Maria Luisa, and their acts of artistic, literary, scientific, and architectural patronage that contributed to the cultural heritage of Florence, Italy. This thesis also explores relevant social, political, economic, and geopolitical conditions over the course of the Medici dynasty, and incorporates primary research derived from a conversation and an interview with specialists in Florence in order to present a more contextual analysis. -

Santa Maria Del Fiore: a Philosophical Context for Understanding Dome Construction During the Italian Renaissance

The Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore by Brunelleschi, c. 1420-1436, Florence Photos courtesy Adrielle Kent (web sources) Santa Maria del Fiore: A Philosophical Context for Understanding Dome Construction During the Italian Renaissance Adrielle Kent In the early 1420‘s, Filippo Brunelleschi Brunelleschi (1377-1446) began one of the most ambitious Brunelleschi‘s father, a notary and architectural feats ever attempted. His task counselor for the city of Florence, was on the was to construct a dome to crown Santa Maria committee of 1367 charged with planning the del Fiore, the primary cathedral in Florence. dome, so Brunelleschi grew up with the Brunelleschi was able to provide a unfinished cathedral, which may have comprehensive solution to the complex inspired him. Little is known about his early engineering problems involved in building a life, but it is documented that he became a round dome of that magnitude. His goldsmith after his father‘s unsuccessful ingenuous design made it possible for him to attempt to make him a notary (Jackson, p.27). build the highest dome up to that time and the He became a member of the Goldsmith‘s largest since Hadrian‘s Pantheon in Rome. Guild in 1401 (Hughes and Lynton, p. 16). A Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) stated about the crucial moment in his career came when he architect, ―[Brunelleschi is] like Giotto, participated in a contest to create a set of meager in person but of a genius so lofty that metal doors in relief sculpture for the many say he was given to us by Heaven to baptistery of Santa Maria del Fiore. -

The Fresco Decoration of the Oratorio Dei Buonomini Di San Martino: Piety and Charity in Late-Fifteenth Century Florence a Thesi

Birmingham City University The Fresco Decoration of the Oratorio dei Buonomini di San Martino: Piety and Charity in Late-Fifteenth Century Florence 2 Volumes A Thesis in Art History by Samantha J.C. Hughes-Johnson Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2016 Volume I Abstract Despite the emergence of various studies focusing on Florentine lay sodalities, the Procurators of the Shamed Poor of Florence, otherwise known as the Buonomini di San Martino, have received little attention from social historians and much less consideration from historians of art. Consequently, there are several distinct research gaps concerning the charitable operations of this lay confraternity and the painted decorations within its oratory that beg to be addressed. The greatest research breach pertains to the fresco decoration of the San Martino chapel as, despite the existence of various pre- iconographic descriptions of the murals, comprehensive iconographic and comparative analyses of these painted works have never before been carried out. Moreover, the dating of the entire cycle and the attribution of one of its lunette paintings is questionable. Accordingly, the present study addresses these deficiencies. Central to the current research is an original, in-depth art historical analysis of the frescoed paintings. Involving the methodologies of iconographic and comparative analyses alongside connoisseurship, the present investigation has allowed the researcher to establish the following: the art historical significance of the oratory murals; the dating of the fresco cycle; the attribution of an executor for the Dream of Saint Martin fresco; the identification of portraits of Lorenzo and Giuliano de’ Medici within the Buonomini cycle; the disclosure of the shamed poor as non-patrician representatives of Florence. -

Perspectives on Medieval Florentine Narratives Within Their Context

L2 Journal, Volume 4 (2012), pp. 142-170 Bridging Language and History in an Advanced Italian Classroom: Perspectives on Medieval Florentine Narratives within their Context MARCO PRINA University of California, Berkeley 142-170 E-mail: [email protected] Among the challenges faced by L2 instructors is the inclusion of historical memories. Although they are foundational to a culture’s identity, sometimes they are so far removed from students’ present reality that they have no familiarity with them. Meeting this challenge requires the development of activities that contextualize these narratives while bridging the past and the present by engaging with learners’ own values and experiences. This article presents a model didactic unit drawn from a particular aspect of the Italian culture, namely, the medieval Florentine narratives. At the same time, the strategies and tools that are proposed can be implemented to explore virtually any historical memories in other L2 courses. _______________ INTRODUCTION One of the major challenges in fostering a cross-fertilized continuity between language and culture in the L2 classroom is the integration of cultural narratives (see, e.g., Kramsch, 1993; MLA 2007; Byrnes, 2010). However, L2 scholarship has been virtually silent regarding the specific issue of the inclusion of narrative cultural memories. Although these memories have been recognized as foundational in activating the collective remembering process (Wertsch, 2002), they reside so far in the past that language learners and even some native speakers may have difficulty relating to them. Indeed, even in an academic context, these cultural memories tend to be presented as self-contained artifacts rather than as valuable experiences for the learners.