European Commission 70 4.2

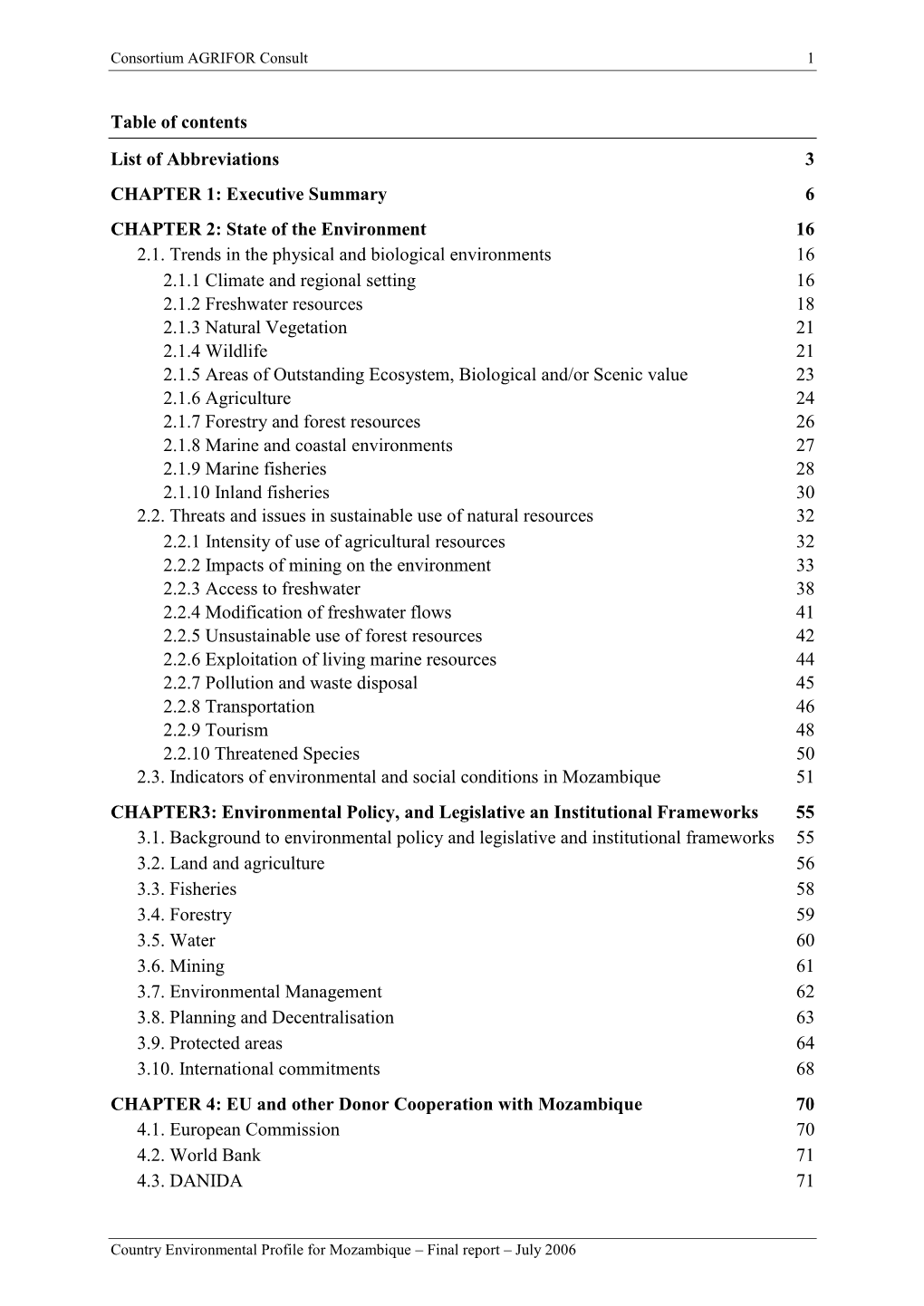

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hydrobiological Assessment of the Zambezi River System: a Review

WORKING PAPER HYDROBIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT OF THE ZAMBEZI RWER SYSTEM: A REVIEW September 1988 W P-88-089 lnlernai~onallnsl~iule for Appl~rdSysiems Analysis HYDROBIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT OF THE ZAMBEZI RIVER SYSTEM: A REVIEW September 1988 W P-88-089 Working Papers are interim reports on work of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis and have received only limited review. Views or opinions expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the Institute or of its National Member Organizations. INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR APPLIED SYSTEMS ANALYSIS A-2361 Laxenburg, Austria One of the Lmporhnt Projects within the Environment Program is that entitled: De- *on apport *stems jbr Mancrgfnq Lurge Intemartiorrcrl Rivers. Funded by the Ford Foundation, UNEP, and CNRS France, the Project includes two case stu- dies focused on the Danube and the Zambezi river basins. The author of this report, Dr. G. Pinay, joined IIASA in February 1987 after completing his PhD at the Centre dSEmlogie des Ressources Renouvelables in Toulouse. Dr. Pinny was assigned the task of reviewing the published literature on water management issues in the Zambezi river basin, and related ecological ques- tions. At the outset, I thought that a literature review on the Zambezi river basin would be a rather slim report. I am therefore greatly impressed with this Working Paper, which includes a large number of references but more importantly, syn- thesizes the various studies and provides the scientific basis for investigating a very complex set of management issues. Dr. Pinay's review will be a basic refer- ence for further water management studies in the Zambezi river basin. -

Breaking Into the Smallholder Seed Market

BREAKING LESSONS FROM THE MOZAMBIQUE SMALLHOLDER INTO THE EFFECTIVE EXTENSION DRIVEN SMALLHOLDER SUCCESS (SEEDS) PROJECT SEED MARKET Pippy Gardner © 2017 NCBA CLUSA NCBA CLUSA 1775 Eye Street, N.W. Suite 800 Washington, D.C. 20006 SMALLHOLDER EFFECTIVE EXTENSION DRIVEN SUCCESS PROJECT 2017 WHITE PAPER LESSONS LEARNED FROM BREAKING INTO THE MOZAMBIQUE SEEDS THE SMALLHOLDER PROJECT SEED MARKET DECEMBER 2017 Table of Contents 2 Executive Summary 6 Introduction 7 The Seeds Industry in Mozambique 8 Background to the SEEDS Project and Partners 9 Rural Agrodealer Models and Mozambique 11 Activities Implemented and Main Findings/ Reccomendations 22 Seeds Sales 30 Sales per Value Chain 33 Conclusion 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY BREAKING INTO THE SMALLHOLDER IDENTIFICATION OF CBSPS SEEDS MARKET By project end, 289 CBSPs (36 Oruwera CBSPs and uring its implementation over two agricultural 153 Phoenix CBSPs) had been identified, trained, and Dcampaigns between 2015 and 2017, the contracted by Phoenix and Oruwera throughout the Smallholder Effective Extension Driven Success three provinces. CBSPs were stratified into two main (SEEDS) project, implemented by NCBA CLUSA profiles: 1) smaller Lead Farmer CBSPs working with in partnership with Feed the Future Partnering for NCBA CLUSA’s Promotion of Conservation Agriculture Innovation, a USAID-funded program, supported Project (PROMAC) who managed demonstration two private sector seed firms--Phoenix Seeds and plots to promote the use of certified seed and Oruwera Seed Company--to develop agrodealer marketed this same product from their own small networks in line with NCBA CLUSA’s Community stores, and 2) larger CBSP merchants or existing Based Service Provider (CBSP) model in the agrodealers with a greater potential for seed trading. -

Angoche: an Important Link of the Zambezian Gold Trade Introduction

Angoche: An important link of the Zambezian gold trade CHRISTIAN ISENDAHL ‘Of the Moors of Angoya, they are as they were: they ruin the whole trade of Sofala.‘ Excerpt from a letter from Duarte de Lemos to the King of Portugal, dated the 30th of September, 1508 (Theal 1964, Vol. I, p. 73). Introduction During the last decade or so a significant amount of archaeological research has been devoted to the study of early urbanism along the east African coast. In much, this recent work has depended quite clearly upon the ground-breaking fieldwork conducted by James Kirkman and Neville Chittick in Kenya and Tanzania during the 1950´s and 1960´s. Notwithstanding the inevitable and, at times, fairly apparent shortcomings of their work and their basic theoretical explanatory frameworks, it has provided a platform for further detailed studies and rendered a wide flora of approaches to the interpretation of the source materials in recent studies. In Mozambique, however, recent archaeological research has not benefited from such a relatively strong national tradition of research attention. The numerous early coastal settlements lining the maritime boundaries of the nation have, in a very limited number, been the target of specialized archaeological fieldwork and analysis only for two decades. The most important consequence has been that research directed towards thematically formulated archaeological questions has had to await the gathering of basic information through field surveys and recording of existing sites as well as the construction and perpetual analysis and refinement of basic chronostratigraphic sequences. Furthermore, the lack of funding, equipment and personnel – coupled with the geographical preferentials of those actually active – has resulted in a yet quite fragmented archaeological database of early urbanism in the country. -

Joint Communiqué by the African Commission on Human and People’S Rights (ACHPR), the Special Rapporteur on Refugees, Asylum-Seekers, Migrants in Africa, Ms

Joint Communiqué by the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights (ACHPR), the Special Rapporteur on refugees, asylum-seekers, migrants in Africa, Ms. Maya Sahli Fadel, and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) on Mozambique's displacement crisis and forced returns from Tanzania (1) Situation of IDPs in Mozambique - The total number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Cabo Delgado Province has reached more than 732,000 according to humanitarian estimates. Approximately 46% are children. The conflict in northern Mozambique has left tens of thousands of people dead or injured. Civilians have been exposed to a variety of protection concerns, including physical assault, kidnappings, murder of family members, and gender-based violence (GBV). Moreover, the conflict has resulted in families being separated, and in many cases being displaced multiple times as they seek safety. - The situation, which has become a protection crisis, substantially worsened after attacks by non-state armed groups in the city of Palma on 24 March this year. Humanitarian actors are seeing an escalating rate of displacement, along with an increase in the proportion of displaced people having directly experienced human rights violations. There is also a growing number of particularly vulnerable persons among the IDPs, such as elderly, unaccompanied and separated children, pregnant women as well as those with urgent need for shelter, food and access to health structures. - Ongoing insecurity has forced thousands of families to seek refuge mostly in the south of Cabo Delgado and Nampula Provinces, as well as in Niassa and Zambezia provinces. Cabo Delgado’s districts of Ancuabe, Balama, Chiure, Ibo, Mecufi, Metuge, Montepuez, Mueda, Namuno, Nangade and Pemba continue to register new arrivals every day. -

Final Report for WWF

Intermediate Technology Consultants Ltd Final Report for WWF The Mphanda Nkuwa Dam project: Is it the best option for Mozambique’s energy needs? June 2004 WWF Mphanda Nkuwa Dam Final Report ITC Table of Contents 1 General Background.............................................................................................................................6 1.1 Mozambique .................................................................................................................................6 1.2 Energy and Poverty Statistics .....................................................................................................8 1.3 Poverty context in Mozambique .................................................................................................8 1.4 Energy and cross-sectoral linkages to poverty ........................................................................11 1.5 Mozambique Electricity Sector.................................................................................................12 2 Regional Electricity Market................................................................................................................16 2.1 Southern Africa Power Pool......................................................................................................16 3 Energy Needs.......................................................................................................................................19 3.1 Load Forecasts............................................................................................................................19 -

Living Lakes Goals 2019 - 2024 Achievements 2012 - 2018

Living Lakes Goals 2019 - 2024 Achievements 2012 - 2018 We save the lakes of the world! 1 Living Lakes Goals 2019-2024 | Achievements 2012-2018 Global Nature Fund (GNF) International Foundation for Environment and Nature Fritz-Reichle-Ring 4 78315 Radolfzell, Germany Phone : +49 (0)7732 99 95-0 Editor in charge : Udo Gattenlöhner Fax : +49 (0)7732 99 95-88 Coordination : David Marchetti, Daniel Natzschka, Bettina Schmidt E-Mail : [email protected] Text : Living Lakes members, Thomas Schaefer Visit us : www.globalnature.org Graphic Design : Didem Senturk Photographs : GNF-Archive, Living Lakes members; Jose Carlo Quintos, SCPW (Page 56) Cover photo : Udo Gattenlöhner, Lake Tota-Colombia 2 Living Lakes Goals 2019-2024 | Achievements 2012-2018 AMERICAS AFRICA Living Lakes Canada; Canada ........................................12 Lake Nokoué, Benin .................................................... 38 Columbia River Wetlands; Canada .................................13 Lake Ossa, Cameroon ..................................................39 Lake Chapala; Mexico ..................................................14 Lake Victoria; Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda ........................40 Ignacio Allende Reservoir, Mexico ................................15 Bujagali Falls; Uganda .................................................41 Lake Zapotlán, Mexico .................................................16 I. Lake Kivu; Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda 42 Laguna de Fúquene; Colombia .....................................17 II. Lake Kivu; Democratic -

Disentangling Violent Extremism in Cabo Delgado Province, Northern Mozambique: Challenges and Prospects

CHAPTER 15 Disentangling Violent Extremism in Cabo Delgado Province, Northern Mozambique: Challenges and Prospects Blessed Mangena and Mokete Pherudi Introduction Radicalisation and violent extremism in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province1 are on the rise and are posing a major threat to human security and develop- ment in the region. This study sought to investigate the nature of the challenges that the Mozambique government is encountering in addressing the violent extremism posed by Ansar al-Sunnah (also sometimes referred to as Ahlu Sunna Wa-Jama, Ansar al Sunna or Al-Shabaab)2 as well as its prospects in addressing the threat. The study established that Mozambique’s wholly militarised approach to addressing violent extremism in the province, marred by human rights abuses, could worsen the problem. The country is at risk of following the path of Nigeria, where a ham-fisted government response to a radical sect led to a surge in support for the group that became Boko Haram.3 However, there is a good chance that the insurgency in Mozambique might be contained if the government embraces holistic, comprehensive and integrated counter-extremism strategies that encom- pass dynamic military approaches fused with sustained efforts that are aimed at effectively addressing the root causes of extremism in the province. The Mozambican government also has a better chance of containing the threat if it can curb the extremist group’s source of funding, which has enabled it to expand its war chest. Basically, there are two factors driving the conflict in Cabo Delgado province. The first is insurgency capacity to recruit more militants through enticing them with financial incentives that are donated by sympathisers, 348 Disentangling Violent Extremism in Cabo Delgado Province who donate via electronic payments. -

SERIE TERRA E AGUA Areas De Rega

SERIE TERRA E AGUA DO INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE INVESTIGACAO AGRONOMICA COMUNICACAO No.53 Areas de Rega: Inventario e Possibilidades Futuras D. Mihajlovich F. Gomes 1986 Maputo, Mopambique AREAS DE RE6A: INVENTARIO E POSSIBILIDADES FUTURAS D. Mihajlovich F. Gomes 1986 Maputo, Mogambique Scanned from original by ISRIC - World Soil Information, as ICSU World Data Centre for Soils. The purpose is to make a safe depository for endangered documents and to make the accrued information available for consultation, following Fair Use Guidelines. Every effort is taken to respect Copyright of the materials within the archives where the identification of the Copyright holder is clear and, where feasible, to contact the originators. For questions please contact soil, [email protected] indicating the item reference number concerned. iSH^Io INDICE RESUMO 1 - Introducao 2 - Objectivos 3 - Material e metodo 4 - Breve referenda aos Recursos Naturais 5 - Resultados 5.1 Por Bacia Hidrogra'fica 5.2 Por Provincia 5.3 Aproveitanento das areas de rega 6 - Conclusoes Gerais 7 - Recomendacoes ANEXO I - Principais pessoas entrevistadas ANEXO II - Map 1 - Classificacao Climatica - Koppen Map 2 - Grandes zonas climaticas de acordo com o indice de humidade Map 3 - Precipitacao media anual Map 4 - Zonas climaticamente aptas para a agricultura irrigada ANEXO III - Areas de rega Anexo IV - Map 5 - Areas Irrigadas - Inventario e possibilidades futuras. LISTA DB ABRBVIATOBAS DNA - Direccao Nacional de Aguas SEHA — Secretaria de Estado da Hidraulica Agricola INIA - Instituto Nacional de Investigacao Agronémica DNTA - Direccao Nacional de Técnica Agraria DPA - Direccao Provincial de Agricultura DDA - ünidade de Direccao Agricola RESUMO Este estudo realiza-se no ambito, das actividades do projecto MOZ 81/015 do Departamento de Terra e Agua do Instituto Nacional de Investigacao Agronómica de Mozambique e destina-se a completar o Inventario Nacional Agroecoló'gico. -

Micro and Small-Scale Industry Development in Cabo Delgado Province in Mozambique

CMIREPORT Micro and Small-scale Industry Development in Cabo Delgado Province in Mozambique Jan Isaksen Carlos Rafa Mate R 2005: 10 Micro and Small-scale Industry Development in Cabo Delgado Province in Mozambique Jan Isaksen Carlos Rafa Mate R 2005: 10 CMI Reports This series can be ordered from: Chr. Michelsen Institute P.O. Box 6033 Postterminalen, N-5892 Bergen, Norway Tel: + 47 55 57 40 00 Fax: + 47 55 57 41 66 E-mail: [email protected] www.cmi.no Price: NOK 50 ISSN 0805-505X ISBN 82-8062-120-2 This report is also available at: www.cmi.no/publications Indexing terms Small-scale industry Industurial development Capacity building Mozambique Project number 24066 Project title Evaluation of the Cabo Delgado Project CMI REPORT MICRO AND SMALL-SCALE INDUSTRY DEVELOPMENT IN CABO DELGADO PROVINCE R 2005: 10 Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................................................................... IV EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................................V 1. BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................................................................1 2. SOCIO-ECONOMIC AND INSTITUTIONAL SETTING..........................................................................3 2.1 ECONOMY ...........................................................................................................................................................3 -

Struggle for Survival

M N G u o E T o OZA STRUGGLE FOR SURVIVAL Mozambique's History: In 1964, led by the Front for the libera Mozambique tion of Mozambique (FRELlMO), they Mozambique was a Portuguese colony launched an armed struggle to oust the for more than four hundred years. Portugal Portuguese. Ten years later, in 1974, Por was a poor country itself, unable and un tuguese army officers rebelled against their own government, ending decades of Natala willing to develop Mozambique's economic potential. The Portuguese profited from ex fascist rule within Portugal. In the following porting Mozambican labor to the South y~ar , Mozambique won independence, as African mines and exporting agricultural did the other Portuguese colonies of products such as cotton, tea, and cashew Angola and Guinea Bissau. nuts. Mozambican peasants were forced to Mozambique's new Frelimo government grow these crops under brutal conditions. established a nonaligned socialist model of They were forced to work on government development, which included a non-racial projects such as road and railway con policy of inclusion, provision of education (J struction under conditions considered to be and health services, and a plan to in among the worst in African colonial history. tegrate women equally into the new Mozambique is twice the size of Cali society. fornia and strategically located on the TRANSPORT LINKS TO PORTS OF BEIRA Indian Ocean, with a coastline equivalent NACALA AND MAPUTO - MAIN TARGETS ' to that of the United States from Boston to OF SOUTH AFRICAN SABOTAGE Miami. It has been generously endowed POPULATION 15 MILLION with mineral resources. -

Cahora Bassa North Bank Hydropower Project

Hydropower Sustainability Assessment Protocol: Cahora Bassa North Bank Hydropower Project Cahora Bassa North Bank Hydropower Project Public Disclosure Authorized Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa Public Disclosure Authorized Zambezi River Basin Introduction The hydropower resources of the Zambezi River Basin are central to sustaining economic development and prosperity across southern Africa. The combined GDP among the riparian states is estimated at over US$100 billion. With recognition of the importance of shared prosperity and increasing commitments toward regional integration, there is significant potential for collective development of the region’s rich natural endowments. Despite this increasing prosperity, Contents however, poverty is persistent across the basin and coefficients of inequality for some of the riparian states are among the highest in Introduction .......................................................................................... 1 the world. Public Disclosure Authorized The Hydropower Sustainability Assessment Protocol ......................... 4 Reflecting the dual nature of the regional economy, new investments The Project ............................................................................................ 3 in large infrastructure co-exist alongside a parallel, subsistence economy that is reliant upon environmental services provided by the The Process ........................................................................................... 8 river. Appropriate measures are therefore needed to balance -

Geology and Geomorphology of the Urema Graben with Emphasis on the Evolution of Lake Urema

Journal of African Earth Sciences 58 (2010) 272–284 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of African Earth Sciences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jafrearsci Geology and geomorphology of the Urema Graben with emphasis on the evolution of Lake Urema Franziska Steinbruch * Scientific Services of Gorongosa National Park, Avenida do Poder Popular 264, Beira, Mozambique article info abstract Article history: The Lake Urema floodplain belongs to the Urema Catchment and is located in the downstream area of the Received 19 December 2008 Pungwe River basin in Central Mozambique. The floodplain is situated in the Urema Graben, which is the Received in revised form 8 February 2010 southern part of the East African Rift System. Little geological information exists about this area. The cir- Accepted 12 March 2010 culated information is not readily available, and is often controversial and incomplete. In this paper the Available online 20 March 2010 state of knowledge about the geology and tectonic evolution of the Lake Urema wetland area and the Urema Catchment is compiled, reviewed and updated. This review is intended to be a starting point Keywords: for approaching practical questions such as: How deep is the Urema Graben? What controls the hydrol- East African Rift System ogy of Lake Urema? Where are the hydrogeological boundaries? Where are the recharge areas of the Lake Floodplain Hydrogeology Urema floodplain? From there information gaps and needs for further research are identified. Lake Urema Ó 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Mozambique 1. Introduction 2. Regional geology and tectonic evolution The Lake Urema floodplain belongs to the Urema Catchment 2.1.