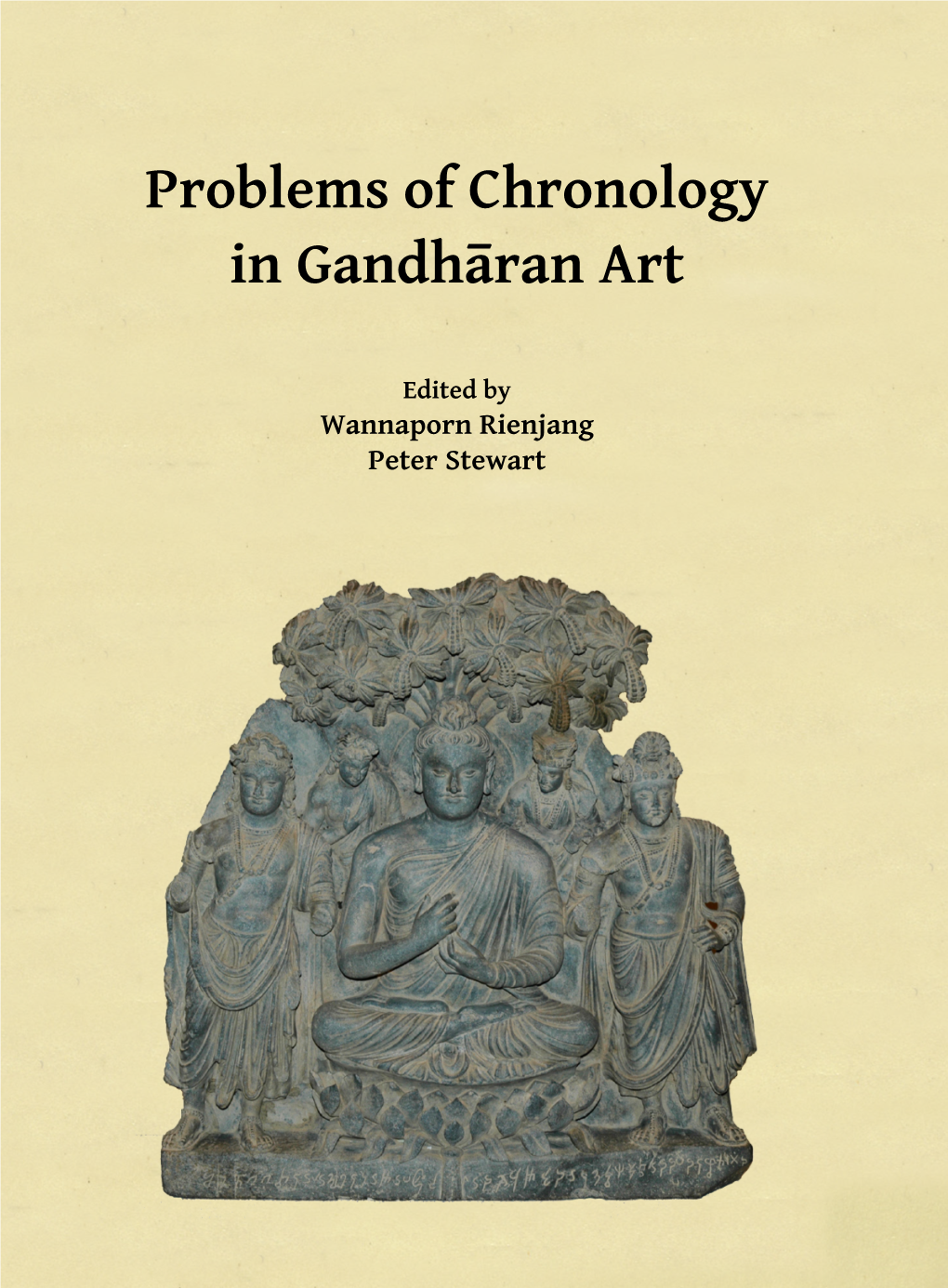

Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas Sanjay Sharma Introduction In the post-Vedic period, the centre of activity shifted from the upper Ganga valley or madhyadesha to middle and lower Ganga valleys known in the contemporary Buddhist texts as majjhimadesha. Painted grey ware pottery gave way to a richer and shinier northern black polished ware which signified new trends in commercial activities and rising levels of prosperity. Imprtant features of the period between c. 600 and 321 BC include, inter-alia, rise of ‘heterodox belief systems’ resulting in an intellectual revolution, expansion of trade and commerce leading to the emergence of urban life mainly in the region of Ganga valley and evolution of vast territorial states called the mahajanapadas from the smaller ones of the later Vedic period which, as we have seen, were known as the janapadas. Increased surplus production resulted in the expansion of trading activities on one hand and an increase in the amount of taxes for the ruler on the other. The latter helped in the evolution of large territorial states and increased commercial activity facilitated the growth of cities and towns along with the evolution of money economy. The ruling and the priestly elites cornered most of the agricultural surplus produced by the vaishyas and the shudras (as labourers). The varna system became more consolidated and perpetual. It was in this background that the two great belief systems, Jainism and Buddhism, emerged. They posed serious challenge to the Brahmanical socio-religious philosophy. These belief systems had a primary aim to liberate the lower classes from the fetters of orthodox Brahmanism. -

And Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Raven and the Serpent: "The Great All- Pervading R#hula" Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet Cameron Bailey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE RAVEN AND THE SERPENT: “THE GREAT ALL-PERVADING RHULA” AND DMONIC BUDDHISM IN INDIA AND TIBET By CAMERON BAILEY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Religion Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Cameron Bailey defended this thesis on April 2, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bryan Cuevas Professor Directing Thesis Jimmy Yu Committee Member Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my adviser Dr. Bryan Cuevas who has guided me through the process of writing this thesis, and introduced me to most of the sources used in it. My growth as a scholar is almost entirely due to his influence. I would also like to thank Dr. Jimmy Yu, Dr. Kathleen Erndl, and Dr. Joseph Hellweg. If there is anything worthwhile in this work, it is undoubtedly due to their instruction. I also wish to thank my former undergraduate advisor at Indiana University, Dr. Richard Nance, who inspired me to become a scholar of Buddhism. -

Imagining Ritual and Cultic Practice in Koguryŏ Buddhism

International Journal of Korean History (Vol.19 No.2, Aug. 2014) 169 Imagining Ritual and Cultic Practice in Koguryŏ Buddhism Richard D. McBride II* Introduction The Koguryŏ émigré and Buddhist monk Hyeryang was named Bud- dhist overseer by Silla king Chinhŭng (r. 540–576). Hyeryang instituted Buddhist ritual observances at the Silla court that would be, in continually evolving forms, performed at court in Silla and Koryŏ for eight hundred years. Sparse but tantalizing evidence remains of Koguryŏ’s Buddhist culture: tomb murals with Buddhist themes, brief notices recorded in the History of the Three Kingdoms (Samguk sagi 三國史記), a few inscrip- tions on Buddhist images believed by scholars to be of Koguryŏ prove- nance, and anecdotes in Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms (Samguk yusa 三國遺事) and other early Chinese and Japanese literary sources.1 Based on these limited proofs, some Korean scholars have imagined an advanced philosophical tradition that must have profoundly influenced * Associate Professor, Department of History, Brigham Young University-Hawai‘i 1 For a recent analysis of the sparse material in the Samguk sagi, see Kim Poksun 金福順, “4–5 segi Samguk sagi ŭi sŭngnyŏ mit sach’al” (Monks and monasteries of the fourth and fifth centuries in the Samguk sagi). Silla munhwa 新羅文化 38 (2011): 85–113; and Kim Poksun, “6 segi Samguk sagi Pulgyo kwallyŏn kisa chonŭi” 存疑 (Doubts on accounts related to Buddhism in the sixth century in the Samguk sagi), Silla munhwa 新羅文化 39 (2012): 63–87. 170 Imagining Ritual and Cultic Practice in Koguryŏ Buddhism the Sinitic Buddhist tradition as well as the emerging Buddhist culture of Silla.2 Western scholars, on the other hand, have lamented the dearth of literary, epigraphical, and archeological evidence of Buddhism in Kogu- ryŏ.3 Is it possible to reconstruct illustrations of the nature and characteris- tics of Buddhist ritual and devotional practice in the late Koguryŏ period? In this paper I will flesh out the characteristics of Buddhist ritual and devotional practice in Koguryŏ by reconstructing its Northeast Asian con- text. -

Symbolism of the Buddhist Stūpa

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Gregory Schopen Roger Jackson Indiana University Fairfield University Bloomington, Indiana, USA Fairfield, Connecticut, USA EDITORS Peter N. Gregory Ernst Steinkellner University of Illinois University of Vienna Urbana-Champaign, Illinois, USA Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki Universite de Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo, Japan Bardxvell Smith Robert Thurman Carleton College Amherst College Northfteld, Minnesota, USA Amherst, Massachusetts, USA ASSISTANT EDITOR Bruce Cameron Hall College of William and Mary Williamsburg, Virginia, USA Volume 9 1986 Number 2 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES 1. Signs, Memory and History: A Tantric Buddhist Theory of Scriptural Transmission, by Janet Gyatso 7 2. Symbolism of the Buddhist Stupa, by Gerard Fussman 37 3. The Identification of dGa' rab rdo rje, by A. W. Hanson-Barber 5 5 4. An Approach to Dogen's Dialectical Thinking and Method of Instantiation, by Shohei Ichimura 65 5. A Report on Religious Activity in Central Tibet, October, 1985, by Donald S. Lopez, Jr. and Cyrus Stearns 101 6. A Study of the Earliest Garbha Vidhi of the Shingon Sect, by Dale Allen Todaro 109 7. On the Sources for Sa skya Panclita's Notes on the "bSam yas Debate," by Leonard W.J. van der Kuijp 147 II. BOOK REVIEWS 1. The Bodymind Experience in Japanese Buddhism: A Phenomenological Study ofKukai and Dogen, by D. Shaner (William Waldron) 155 2. A Catalogue of the s Tog Palace Kanjur, by Tadeusz Skorupski (Bruce Cameron Hall) 156 3. Early Buddhism and Christianity: A Comparative Study of the Founders' Authority, the Community, and the Discipline, by Chai-Shin Yu (Vijitha Rajapakse) 162 4. -

Depiction of Asoka Raja in the Buddhist Art of Gandhara

Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan Volume No. 54, Issue No. 2 (July - December, 2017) Mahmood-ul-Hasan * DEPICTION OF ASOKA RAJA IN THE BUDDHIST ART OF GANDHARA Abstract Asoka was the grandson of the Chndragupta Maurya, founder of one of the greatest empires of the ancient India (321-297 BC). The empire won by Chandragupta had passed to his son Bindusara, after his death, it was again transmitted to his son Asoka. During early years of his kingship he was a very harsh ruler. But after witnessing the miseries and suffering of people during the Kalinga War (260 BCE.) Ashoka converted to Buddhism and decided to substitute the reign of the peace and tranquility for that of violence. Due to his acts of piety and love for the Buddhist faith he become the most popular and personality after Buddha for the Buddhists. Many legends associated with him i.e. “a handful dust”, “redistribution of Relics”, “ his visit of underwater stupa at Ramagrama” are depicted in Gandhara Art. In the present article an effort has been made to identify and analyze the legends of Ashoka in the light of their historical background. Keywords: Chandragupta Maurya, Bindusara, Ashoka, Kalanga war, Buddhism. Introduction The Buddhist Art of Gandhara came in to being in the last century before the Christian era, when the Sakas were ruling in the North-West (Marshall, 1973:17) and further developed during the Parthian period (1st century A.D.). Like the Sakas, the Parthians were confirmed philhellenes and proud of their Hellenistic culture, and not only had they large numbers of Greek subjects in their empire but they were in a position to maintain close commercial contacts with the Mediterranean coasts (Ibid: 6). -

Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Outlines of Indian History Module Name/Title Mahajanapadas- Rise of Magadha – Nandas – Invasion of Alexander Module Id I C/ OIH/ 08 Pre requisites Early History of India Objectives To study the Political institutions of Ancient India from earliest to 3rd Century BCE. Mahajanapadas , Rise of Magadha under the Haryanka, Sisunaga Dynasties, Nanda Dynasty, Persian Invasions, Alexander’s Invasion of India and its Effects Keywords Janapadas, Magadha, Haryanka, Sisunaga, Nanda, Alexander E-text (Quadrant-I) 1. Sources Political and cultural history of the period from C 600 to 300 BCE is known for the first time by a possibility of comparing evidence from different kinds of literary sources. Buddhist and Jaina texts form an authentic source of the political history of ancient India. The first four books of Sutta pitaka -- the Digha, Majjhima, Samyutta and Anguttara nikayas -- and the entire Vinaya pitaka were composed between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. The Sutta nipata also belongs to this period. The Jaina texts Bhagavati sutra and Parisisthaparvan represent the tradition that can be used as historical source material for this period. The Puranas also provide useful information on dynastic history. A comparison of Buddhist, Puranic and Jaina texts on the details of dynastic history reveals more disagreement. This may be due to the fact that they were compiled at different times. Apart from indigenous literary sources, there are number of Greek and Latin narratives of Alexander’s military achievements. They describe the political situation prevailing in northwest on the eve of Alexander’s invasion. -

Karma and the Animal Realm Envisioned Through an Early Yogācāra Lens

Article Becoming Animal: Karma and the Animal Realm Envisioned through an Early Yogācāra Lens Daniel M. Stuart Department of Religious Studies, University of South Carolina, Rutledge College, Columbia, SC 29208, USA; [email protected] Received: 24 April 2019; Accepted: 28 May 2019; Published: 1 June 2019 Abstract: In an early discourse from the Saṃyuttanikāya, the Buddha states: “I do not see any other order of living beings so diversified as those in the animal realm. Even those beings in the animal realm have been diversified by the mind, yet the mind is even more diverse than those beings in the animal realm.” This paper explores how this key early Buddhist idea gets elaborated in various layers of Buddhist discourse during a millennium of historical development. I focus in particular on a middle period Buddhist sūtra, the Saddharmasmṛtyupasthānasūtra, which serves as a bridge between early Buddhist theories of mind and karma, and later more developed theories. This third- century South Asian Buddhist Sanskrit text on meditation practice, karma theory, and cosmology psychologizes animal behavior and places it on a spectrum with the behavior of humans and divine beings. It allows for an exploration of the conceptual interstices of Buddhist philosophy of mind and contemporary theories of embodied cognition. Exploring animal embodiments—and their karmic limitations—becomes a means to exploring all beings, an exploration that can’t be separated from the human mind among beings. Keywords: Buddhism; contemplative practice; mind; cognition; embodiment; the animal realm (tiryaggati); karma; yogācāra; Saddharmasmṛtyupasthānasūtra 1. Introduction In his 2011 book Becoming Animal, David Abram notes a key issue in the field of philosophy of mind, an implication of the emergent full-blown physicalism of the modern scientific materialist episteme. -

Vii Five Desti Atio S (Pa Cagati)

96 VII FIVE DESTIATIOS ( PACAGATI ) COTETS 1. Hell ( iraya ) 2. Animal Realm ( Tiracchana ) 3. Ghost Realm ( Peta ) 4. Human Realm ( Manussa ) 5. World of Gods ( Devas and Brahmas ) 6. Lifespan of Hell Beings and Petas 7. Lifespan of Celestial Devas 8. Lifespan of Brahmas 9. References 10. Explanatory Notes Five Destinations • 97 What are the Five Destinations? In the Mahasihananda Sutta , Majjhima ikaya Sutta 130, the Buddha mentioned five destinations ( pancagati ) for rebirth. What are the five? Hell , the animal realm, the realm of ghosts, human beings and gods . Hell, animal and ghost realms are woeful states of existence ( duggati ) while the realms of humans and gods are happy states of existence ( sugati ). Here “gods” include the sensuous gods (devas ), the non-sensuous gods of the form plane ( rupa brahmas ), and the non-sensuous gods of the formless plane ( arupa brahmas ). Hell or niraya is believed to exist below the earth’s surface. For example, the Lohakumbhi (Iron Cauldron) hell of hot molten metal mentioned in the Dhammapada Commentary , where the four rich lads had to suffer for committing adultery, is said to be situated below the earth’s crust. The animal, ghost, and human realms exist on the surface of the earth. These realms are not separate, but the beings move about in their own worlds. The gods are believed to live above the earth and high up in the sky in celestial mansions that travel swiftly through the sky ( Vimanavatthu or Mansion Stories). 1. Hell ( iraya ) In Buddhism, beings are born in hell due to their accumulation of weighty bad kamma . -

The Teaching of Buddha”

THE TEACHING OF BUDDHA WHEEL OF DHARMA The Wheel of Dharma is the translation of the Sanskrit word, “Dharmacakra.” Similar to the wheel of a cart that keeps revolving, it symbolizes the Buddha’s teaching as it continues to be spread widely and endlessly. The eight spokes of the wheel represent the Noble Eightfold Path of Buddhism, the most important Way of Practice. The Noble Eightfold Path refers to right view, right thought, right speech, right behavior, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right meditation. In the olden days before statues and other images of the Buddha were made, this Wheel of Dharma served as the object of worship. At the present time, the Wheel is used internationally as the common symbol of Buddhism. Copyright © 1962, 1972, 2005 by BUKKYO DENDO KYOKAI Any part of this book may be quoted without permission. We only ask that Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai, Tokyo, be credited and that a copy of the publication sent to us. Thank you. BUKKYO DENDO KYOKAI (Society for the Promotion of Buddhism) 3-14, Shiba 4-chome, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan, 108-0014 Phone: (03) 3455-5851 Fax: (03) 3798-2758 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.bdk.or.jp Four hundred & seventy-second Printing, 2019 Free Distribution. NOT for sale Printed Only for India and Nepal. Printed by Kosaido Co., Ltd. Tokyo, Japan Buddha’s Wisdom is broad as the ocean and His Spirit is full of great Compassion. Buddha has no form but manifests Himself in Exquisiteness and leads us with His whole heart of Compassion. -

Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies, Vol. 2, May 2012

VOLUME 2 (MAY 2012) ISSN: 2047-1076! ! Journal of the ! ! Oxford ! ! ! Centre for ! ! Buddhist ! ! Studies ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! The Oxford Centre for ! Buddhist Studies A Recognised Independent http://www.ocbs.org/ Centre of the University of Oxford! JOURNAL OF THE OXFORD CENTRE FOR BUDDHIST STUDIES May Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies Volume May : - Published by the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies www.ocbs.org Wolfson College, Linton Road, Oxford, , United Kingdom Authors retain copyright of their articles. Editorial Board Prof. Richard Gombrich (General Editor): [email protected] Dr Tse-fu Kuan: [email protected] Dr Karma Phuntsho: [email protected] Dr Noa Ronkin: [email protected] Dr Alex Wynne: [email protected] All submissions should be sent to: [email protected]. Production team Operations and Development Manager: Steven Egan Production Manager: Dr Tomoyuki Kono Development Consultant: Dr Paola Tinti Annual subscription rates Students: Individuals: Institutions: Universities: Countries from the following list receive discount on all the above prices: Bangladesh, Burma, Laos, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, ailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, In- donesia, Pakistan, all African Countries For more information on subscriptions, please go to www.ocbs.org/journal. Contents Contents List of Contributors Editorial. R G Teaching the Abhidharma in the Heaven of the irty-three, e Buddha and his Mother. A Burning Yourself: Paticca. Samuppāda as a Description of the Arising of a False Sense of Self Modeled on Vedic Rituals. L B A comparison of the Chinese and Pāli versions of the Bala Samyukta. , a collection of early Buddhist discourses on “Powers” (Bala). -

The Buddhist Six-Worlds Model of Consciousness and Reality

THE BUDDHIST SIX-WORLDS MODEL OF CONSCIOUSNESS AND REALITY Ralph Metzner Sonoma, California Historically there have been two main metaphors for consciousness, one spatial or topographical, the other temporal or biographical (Metzner, 1989). The spatial meta phor is expressed in conceptions of consciousness as like a territory, a terrain, or a field, a state one can enter into or leave, or like empty space, as in the Buddhist notion of sunyata.We could speculate that people who unconsciously adhere to a spatial conception of consciousness would tend to a certain kind of fixity of perception and worldview. The "static" aspects of experience might be in the foreground of aware ness, and there could be a craving for stability and persistence. From this point of view, ordinary waking consciousness is the preferred state, and "altered states" are viewed with some anxiety and suspicion-as if an "altered" state is automatically abnormal or pathological in some way. This is close to the attitude of mainstream Western thought toward alterations of consciousness: even the rich diversity of dreamlife and the changed awareness possible with introspection, psychotherapy, or meditation is regarded with suspicion by the dominant extraverted worldview. The temporal metaphor for consciousness on the other hand, is seen in conceptions such as William James' "stream of thought," or the stream of awareness, or the "flow experience"; as well as in developmental theories of consciousness going through various stages. Historically and cross-culturally, we see the temporal metaphor emphasized in the thought of the pre-Socratic philosophers Thales and Heraclitus, in the Buddhist teachings of impermanence (anicca), and in the Taoist emphasis on the flows and eddies of water as the basic underlying pattern of all being. -

Association of Buddhist Studies

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 36 / 37 2013 / 2014 (2015) The Journal of the International EDITORIAL BOARD Association of Buddhist Studies (ISSN 0193-600XX) is the organ of the International Association of KELLNER Birgit Buddhist Studies, Inc. As a peer- STRAUCH Ingo reviewed journal, it welcomes scholarly Joint Editors contributions pertaining to all facets of Buddhist Studies. JIABS is published yearly. BUSWELL Robert CHEN Jinhua The JIABS is now available online in open access at http://journals.ub.uni- COLLINS Steven heidelberg.de/index.php/jiabs. Articles COX Collett become available online for free 24 months after their appearance in print. GÓMEZ Luis O. Current articles are not accessible on- HARRISON Paul line. Subscribers can choose between VON HINÜBER Oskar receiving new issues in print or as PDF. JACKSON Roger Manuscripts should preferably be JAINI Padmanabh S. submitted as e-mail attachments to: KATSURA Shōryū [email protected] as one single file, complete with footnotes and references, KUO Li-ying in two different formats: in PDF-format, LOPEZ, Jr. Donald S. and in Rich-Text-Format (RTF) or MACDONALD Alexander Open-Document-Format (created e.g. by Open Office). SCHERRER-SCHAUB Cristina SEYFORT RUEGG David Address subscription orders and dues, SHARF Robert changes of address, and business correspondence (including advertising STEINKELLNER Ernst orders) to: TILLEMANS Tom Dr. Danielle Feller, IABS Assistant-Treasurer, IABS Department of Slavic and South Asian Studies (SLAS) Cover: Cristina Scherrer-Schaub Anthropole University of Lausanne Font: “Gandhari Unicode” CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland designed by Andrew Glass E-mail: [email protected] (http://andrewglass.org/fonts.php) Web: http://www.iabsinfo.net © Copyright 2015 by the Subscriptions to JIABS are USD 65 per International Association of year for individuals and USD 105 per Buddhist Studies, Inc.