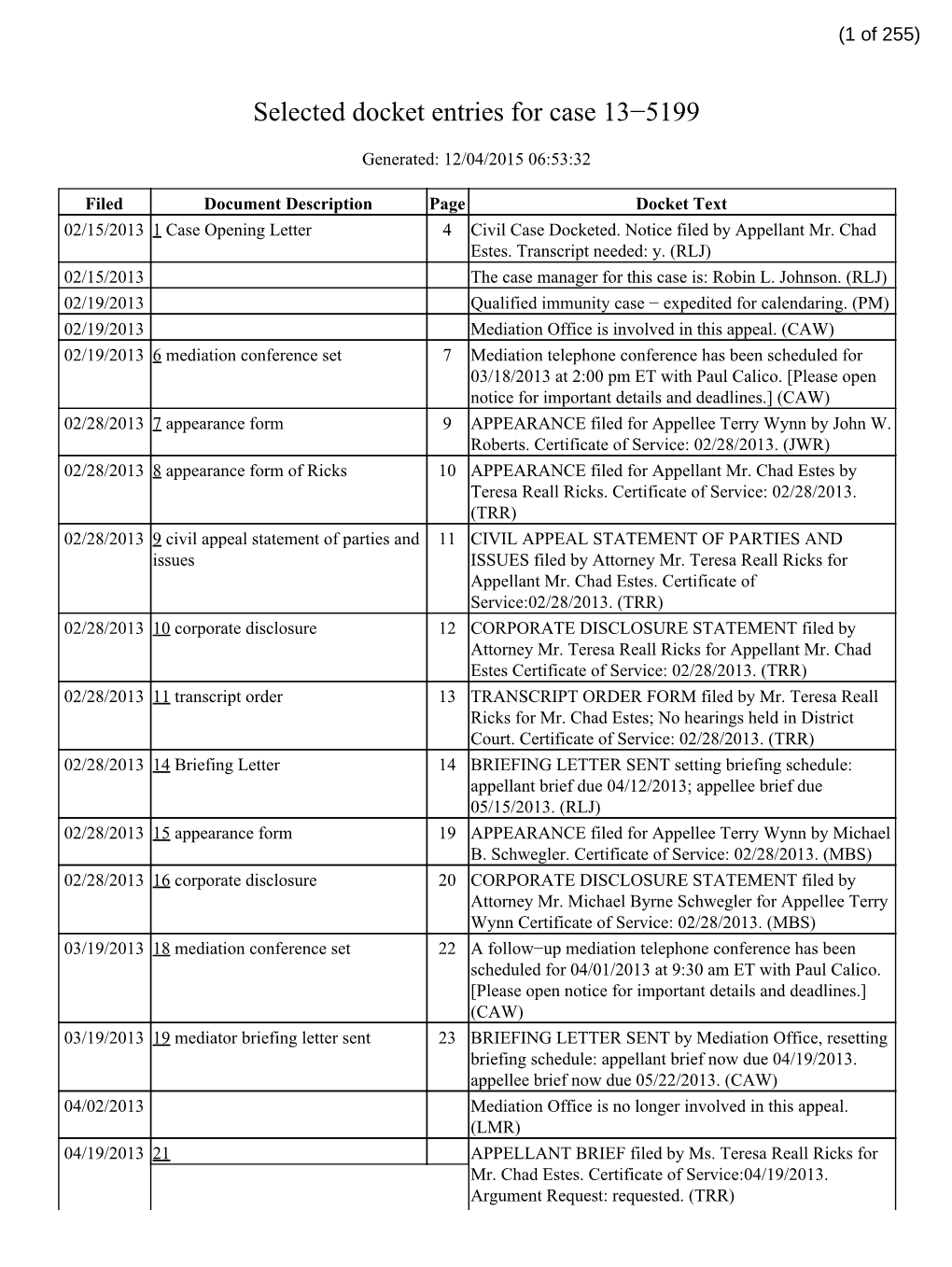

Selected Docket Entries for Case 13−5199

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Courts & Government Offices

COURTS & GOVERNMENT OFFICES Area Code 614 unless otherwise noted COURTS & GOVERNMENT OFFICES FEDERAL COURTS Richard F. Suhrheinrich, Senior Judge U.S. District Court, Southern District of Ohio 241 U.S. Post Office and Federal Building Eastern Division (Columbus) 315 West Allegan U.S. Supreme Court Lansing MI 48933 (517) 377-1513 85 Marconi Blvd., Columbus, OH 43215 One First St. NE Cincinnati Office (513) 564-7466 www.ohsd.uscourts.gov (614) 719-3000 Washington, DC 20543 Eugene E. Siler, Jr., Senior Judge www.supremecourt.gov 310 South Main Street, Room 333 Office of the Clerk Clerk, Scott S. Harris (202) 479-3011 London KY 40741 (606) 877-7930 John Hehman, Clerk of Court Justices Cincinnati Office (513) 564-7469 Room 121 Fx 719-3500 John G. Roberts, Jr., Chief Justice (202) 479-3000 Alice M. Batchelder Division Manager Antonin Scalia (202) 479-3000 143 West Liberty Street Scott Miller 719-3000 Anthony Kennedy (202) 479-3000 Medina OH 44356 (330) 746-6026 U.S. Pretrial Services 719-3170 Clarence Thomas (202) 479-3000 Cincinnati Office (513) 564-7472 U.S. Probation 719-3100 Ruth Bader Ginsburg (202) 479-3000 Martha Craig Daughtrey, Senior Judge Stephen G. Breyer (202) 479-3000 300 Customs House U.S. District Judges Samuel A. Alito, Jr. (202) 479-3000 701 Broadway Edmund A. Sargus, Jr., Chief Judge 719-3240 Sonia Sotomayor (202) 479-3000 Nashville TN 37203 (615) 736-7678 Room 301 Elena Kagan (202) 479-3000 Cincinnati Office (513) 564-7475 Ctrm Deputy Andy Quisumbing 719-3244 Karen Nelson Moore Counselor to the Chief Justice Algenon L. -

Abundant Splits and Other Significant Bankruptcy Decisions

Abundant Splits and Other Significant Bankruptcy Decisions 38th Annual Commercial Law & Bankruptcy Seminar McCall, Idaho Feb. 6, 2020; 2:30 P.M. Bill Rochelle • Editor-at-Large American Bankruptcy Institute [email protected] • 703. 894.5909 © 2020 66 Canal Center Plaza, Suite 600 • Alexandria, VA 22014 • www.abi.org American Bankruptcy Institute • 66 Canal Center Plaza, Suite 600 • Alexandria, VA 22314 1 www.abi.org Table of Contents Supreme Court ........................................................................................................................ 4 Decided Last Term ........................................................................................................................... 5 Nonjudicial Foreclosure Is Not Subject to the FDCPA, Supreme Court Rules ............................. 6 Licensee May Continue Using a Trademark after Rejection, Supreme Court Rules .................. 10 Court Rejects Strict Liability for Discharge Violations ............................................................... 15 Supreme Court Decision on Arbitration Has Ominous Implications for Bankruptcy ................. 20 Decided This Term ......................................................................................................................... 24 Supreme Court Rules that ‘Unreservedly’ Denying a Lift-Stay Motion Is Appealable .............. 25 Supreme Court Might Allow FDCPA Suits More than a Year After Occurrence ....................... 28 Cases Argued So Far This Term .................................................................................................. -

For the Record the Official Newsletter of the John W

For the Record The Official Newsletter of the John W. Peck Cincinnati & Northern Kentucky Chapter Extended Edition, Summer 2018 IN THIS EDITION President’s Message, President’s Message…1 from Dan Donnellon Judges’ Spotlight … 2, 3 I continue to be blessed and Practice Tips: Filing under Seal, impressed by the dedication and Post-Shane Group…5 commitment of the Task Force on Gender Equity in the Courtroom. On Gender Equity Update …7 July 26, we completed our second Skills Training Session (CLE meeting properly as a real leader, Capitol Hill Day Recap…8 pending). The title was “Beyond Oral and select participants got to put Judges’ Night Dinner Recap…9 Advocacy: Practical Skills for Public those skills to use leading a Speaking” and it really lived up to its meeting of their group. Finally, we SDOH Practice Seminar Recap …10 name. We had over 30 registered had an exercise on attendees, the vast majority of which extemporaneous, persuasive The FBA’s SWEL Friendship…11 were women with fewer than 5 years’ speaking. It’s hard to imagine this Fall Mentor Program experience in practice. free CLE was all packed into 90 minutes. And, of course, the event Announcement…12 Judge Tim Black, Magistrate Judge was followed by a brief Happy Stephanie Bowman, and I led the CJA News…13 Hour sponsored by the FBA. faculty along with other talented, Mock Trial Updates…14, 15 younger women lawyers, Jade We also concluded another Smarda (Judge Barrett’s law clerk) excellent program for law students, UC and Chase: Presidential and Mel Matthews (KMK). -

Courts & Government Offices

COURTS & GOVERNMENT OFFICES Area Code 614 unless otherwise noted COURTS & GOVERNMENT OFFICES FEDERAL COURTS Richard F. Suhrheinrich, Senior Judge U.S. District Court, Southern District of Ohio 241 U.S. Post Office and Federal Building Eastern Division (Columbus) 315 West Allegan U.S. Supreme Court Lansing MI 48933 (517) 377-1513 85 Marconi Blvd., Columbus, OH 43215 One First St. NE Cincinnati Office (513) 564-7466 www.ohsd.uscourts.gov (614) 719-3000 Washington, DC 20543 Eugene E. Siler, Jr., Senior Judge www.supremecourt.gov 310 South Main Street, Room 333 Office of the Clerk Clerk, Scott S. Harris (202) 479-3011 London KY 40741 (606) 877-7930 Richard W. Nagel, Clerk of Court Justices Cincinnati Office (513) 564-7469 Room 121 Fx 719-3500 John G. Roberts, Jr., Chief Justice (202) 479-3000 Alice M. Batchelder, Judge Division Supervisor Clarence Thomas (202) 479-3000 143 West Liberty Street Scott Miller 719-3000 Ruth Bader Ginsburg (202) 479-3000 Medina OH 44356 (330) 746-6026 U.S. Pretrial Services 719-3170 Stephen G. Breyer (202) 479-3000 Cincinnati Office (513) 564-7472 U.S. Probation 719-3100 Samuel A. Alito, Jr. (202) 479-3000 Martha Craig Daughtrey, Senior Judge Court Library 719-3180 Sonia Sotomayor (202) 479-3000 300 Customs House Elena Kagan (202) 479-3000 701 Broadway U.S. District Judges Neil M. Gorsuch (202) 479-3000 Nashville TN 37203 (615) 736-7678 Edmund A. Sargus, Jr., Chief Judge 719-3240 Brett M. Kavanaugh (202) 479-3000 Cincinnati Office (513) 564-7475 Room 301 Karen Nelson Moore, Judge Counselor to the Chief Justice Ctrm Deputy Christin Werner 719-3241 Carl B. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 151 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, JUNE 9, 2005 No. 76 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was APPOINTMENT OF ACTING RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY called to order by the Honorable JOHN PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE LEADER E. SUNUNU, a Senator from the State of The PRESIDING OFFICER. The The ACTING PRESIDENT pro tem- New Hampshire. clerk will please read a communication pore. The majority leader is recog- The PRESIDING OFFICER. Today’s to the Senate from the President pro nized. prayer will be offered by the guest tempore (Mr. STEVENS). f chaplain, Bishop Geralyn Wolf of the The legislative clerk read the fol- SCHEDULE Episcopal Diocese of Rhode Island, lowing letter: Providence, RI. Mr. FRIST. Mr. President, this morn- U.S. SENATE, ing we will return to the nomination of PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, PRAYER Washington, DC, June 9, 2005. William Pryor to be a judge of the Eleventh Circuit. Yesterday, cloture The guest Chaplain offered the fol- To the Senate: was invoked by a vote of 76 to 32, and lowing prayer: Under the provisions of rule 1, paragraph 3, of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby we will have the vote on the Pryor Almighty God, to the poor, You have appoint the Honorable JOHN E. SUNUNU, a nomination at 4 p.m. today. Following united us to bring uncommon hope; to Senator from the State of New Hampshire, that vote, we will turn to the consider- innocent captives, release; to the blind, to perform the duties of the Chair. -

Judicial Confirmation Wars: Ideology and the Battle for the Federal Courts, 39 U

University of Richmond Law Review Volume 39 Issue 3 Allen Chair Symposium 2004 Federal Judicial Article 8 Selection 3-2005 Judicial Confirmation Wars: Ideology and the Battle for the edeF ral Courts Sheldon Goldman University of Massachusetts ta Amherst Department of Political Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview Part of the American Politics Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, Judges Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Sheldon Goldman, Judicial Confirmation Wars: Ideology and the Battle for the Federal Courts, 39 U. Rich. L. Rev. 871 (2005). Available at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview/vol39/iss3/8 This Symposium Articles is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Richmond Law Review by an authorized editor of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUDICIAL CONFIRMATION WARS: IDEOLOGY AND THE BATTLE FOR THE FEDERAL COURTS * Sheldon Goldman ** Over the past two decades, there have been highly contentious battles over the confirmation of federal court judges, battles that have been increasing in intensity and number-virtual judicial confirmation wars.' In this Article, I explore why this has come about, focusing on the role of ideology in judicial selection as well as the empirical reality of the confirmation process as it has evolved over the more than a quarter century since Jimmy Carter was elected president. I also explore ways to end these so-called confirmation wars while offering an alternative take on these phenomena. -

Confirmation Hearings on Federal Appointments

S. HRG. 108–135, PT. 7 CONFIRMATION HEARINGS ON FEDERAL APPOINTMENTS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MARCH 24, APRIL 8, JUNE 4, AND JUNE 16, 2004 Serial No. J–108–1 PART 7 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( VerDate 0ct 09 2002 10:53 Nov 17, 2004 Jkt 096683 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 6011 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\96683.TXT SJUD4 PsN: CMORC CONFIRMATION HEARINGS ON FEDERAL APPOINTMENTS VerDate 0ct 09 2002 10:53 Nov 17, 2004 Jkt 096683 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\96683.TXT SJUD4 PsN: CMORC S. HRG. 108–135, PT. 7 CONFIRMATION HEARINGS ON FEDERAL APPOINTMENTS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MARCH 24, APRIL 8, JUNE 4, AND JUNE 16, 2004 Serial No. J–108–1 PART 7 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 96–683 DTP WASHINGTON : 2004 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 10:53 Nov 17, 2004 Jkt 096683 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\96683.TXT SJUD4 PsN: CMORC COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah, Chairman CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania EDWARD M. -

Supreme Court of the United States ------♦ ------ERIC L

No. 09-291 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- ERIC L. THOMPSON, Petitioner, v. NORTH AMERICAN STAINLESS, LP, Respondent. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Sixth Circuit --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- JOINT APPENDIX --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- ERIC SCHNAPPER* LEIGH GROSS LATHEROW* School of Law GREGORY L. MONGE University of Washington WILLIAM H. JONES, JR. P.O. Box 353020 KERI E. LUCAS Seattle, WA 98195 VANANTWERP, MONGE, JONES, (206) 616-3167 EDWARDS & MCCANN, LLP [email protected] 1544 Winchester Avenue, Fifth Floor DAVID O’BRIEN SUETHOLZ P.O. Box 1111 3666 S. Property Rd. Ashland, KY 41105 Eminence, KY 40019 (606) 329-2929 (859) 466-4317 [email protected] LISA S. BLATT Of Counsel: ANTHONY FRANZE ARNOLD & PORTER LLP NATHANIEL K. ADAMS 555 Twelfth St., N.W. General Counsel Washington, D.C. 20004 NORTH AMERICAN STAINLESS (202) 942-5842 6870 Highway 42 East Ghent, KY 41045 Counsel for Petitioner Counsel for Respondent *Counsel of Record *Counsel of Record ================================================================ Petition For Certiorari Filed September 3, 2009 Certiorari Granted June 29, 2010 ================================================================ COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO. (800) 225-6964 -

Judicial Branch

JUDICIAL BRANCH SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES One First Street, NE., Washington, DC 20543 phone (202) 479–3000 JOHN G. ROBERTS, JR., Chief Justice of the United States, was born in Buffalo, NY, January 27, 1955. He married Jane Marie Sullivan in 1996 and they have two children, Josephine and Jack. He received an A.B. from Harvard College in 1976 and a J.D. from Harvard Law School in 1979. He served as a law clerk for Judge Henry J. Friendly of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit from 1979–80 and as a law clerk for then Associate Justice William H. Rehnquist of the Supreme Court of the United States during the 1980 term. He was Special Assistant to the Attorney General, U.S. Department of Justice from 1981–82, Associate Counsel to President Ronald Reagan, White House Coun- sel’s Office from 1982–86, and Principal Deputy Solicitor General, U.S. Department of Justice from 1989–93. From 1986–89 and 1993–2003, he practiced law in Washington, DC. He was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in 2003. President George W. Bush nominated him as Chief Justice of the United States, and he took his seat September 29, 2005. CLARENCE THOMAS, Associate Justice, was born in the Pin Point community near Savannah, Georgia on June 23, 1948. He attended Conception Seminary from 1967–68 and received an A.B., cum laude, from Holy Cross College in 1971 and a J.D. from Yale Law School in 1974. -

For More Information Visit 1

Scan QR code to download the NAMWOLF App For More Information Visit www.namwolf.org 1 Note from Joel Stern On behalf of all of us at NAMWOLF, I want to welcome you to our Annual Meeting and Expo in beautiful Philadelphia. We have a great agenda lined up filled with several high-quality CLE presentations, great keynote speakers, our General Counsel Panel, a Judges Panel, law firm and in-house only sessions, and our expo where in-house counsel can meet formally or informally with our 125 plus NAMWOLF law firms. There is also plenty of opportunity to network and celebrate diversity and inclusion in the legal profession. While we know how busy all of you are, we hope that you take the time to actively participate and develop CONNECTING. or enhance relationships with some amazing people who are so passionate about diversity and inclusion. COMMUNITY. The entire NAMWOLF team, along with several law firm and in- Joel Stern, NAMWOLF CEO house volunteers, has worked hard to make this the best Annual Meeting to date. I want to thank our two law firm co-chairs, Fran Board of Directors Griesing and Joe Tucker and their respective firms for all of their Robin A. Wofford, Chair hard work in planning this meeting. I also want to thank our five Wilson Turner Kosmo LLP in-house co-chairs for their time and effort: Mark Edwards, VP Carla Fields Johnson , Vice Chair & General Counsel, Butamax™ Advanced Biofuels LLC; Anthony Fields & Brown E. Gay, Associate General Counsel, Exelon Business Services At Comcast, the more perspectives Justi Rae Miller,Vice Chair Company; Doug Gaston, Senior Vice President and General Berens & Miller, PA Counsel, Comcast Cable; James Grasty, Vice President and we include, the stronger we are. -

Decision Making in Us Federal Specialized

THE CONSEQUENCES OF SPECIALIZATION: DECISION MAKING IN U.S. FEDERAL SPECIALIZED COURTS Ryan J. Williams A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Kevin T. McGuire Isaac Unah Jason M. Roberts Virginia Gray Brett W. Curry © 2019 Ryan J. Williams ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Ryan J. Williams: The Consequences of Specialization: Decision Making in U.S. Federal Specialized Courts (Under the direction of Kevin T. McGuire) Political scientists have devoted little attention to the role of specialized courts in the United States federal and state judicial systems. At the federal level, theories of judicial decision making and institutional structures widely accepted in discussions of the U.S. Supreme Court and other generalist courts (the federal courts of appeals and district courts) have seen little examination in the context of specialized courts. In particular, scholars are just beginning to untangle the relationship between judicial expertise and decision making, as well as to understand how specialized courts interact with the bureaucratic agencies they review and the litigants who appear before them. In this dissertation, I examine the consequences of specialization in the federal judiciary. The first chapter introduces the landscape of existing federal specialized courts. The second chapter investigates the patterns of recent appointments to specialized courts, focusing specifically on how the qualifications of specialized court judges compare to those of generalists. The third chapter considers the role of expertise in a specialized court, the Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims, and argues that expertise enhances the ability for judges to apply their ideologies to complex, technical cases. -

Judicial Branch

JUDICIAL BRANCH SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES One First Street, NE., 20543, phone (202) 479–3000 JOHN G. ROBERTS, JR., Chief Justice of the United States, was born in Buffalo, NY, January 27, 1955. He married Jane Marie Sullivan in 1996 and they have two children, Josephine and Jack. He received an A.B. from Harvard College in 1976 and a J.D. from Harvard Law School in 1979. He served as a law clerk for Judge Henry J. Friendly of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit from 1979–80 and as a law clerk for then Associate Justice William H. Rehnquist of the Supreme Court of the United States during the 1980 term. He was Special Assistant to the Attorney General, U.S. Department of Justice from 1981–82, Associate Counsel to President Ronald Reagan, White House Coun- sel’s Office from 1982–86, and Principal Deputy Solicitor General, U.S. Department of Justice from 1989–93. From 1986–89 and 1993–2003, he practiced law in Washington, DC. He was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in 2003. President George W. Bush nominated him as Chief Justice of the United States, and he took his seat September 29, 2005. ANTONIN SCALIA, Associate Justice, was born in Trenton, NJ, March 11, 1936. He married Maureen McCarthy and has nine children, Ann Forrest, Eugene, John Francis, Catherine Elisabeth, Mary Clare, Paul David, Matthew, Christopher James, and Margaret Jane. He received his A.B. from Georgetown University and the University of Fribourg, Switzerland, and his LL.B.