The Guitar, the Steamship and the Picnic: England on the Move Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leo Carrillo California History & Art Program

LEO CARRILLO CALIFORNIA HISTORY & ART PROGRAM PROJECT TITLE: Fine-Tuning Guitar Art THEME: Spanish Guitar AGE: Fourth Grade PROJECT INTRODUCTION: Students will learn about the history of the classical Spanish guitar that was a part of the lifestyle at the Leo Carrillo Ranch. Students will be introduced to the famous Mexican folksong “La Golondrina”, a melody played on the guitar and cherished by Leo Carrillo. Students will create and design their own Spanish guitar inspired work of art through mixed media using collage and illustration, personalizing their artwork with intentional images and meaning. ART PROJECT INSPIRATION: SPANISH GUITAR The guitar is one of the most popular and widespread musical instruments played today. It is actually the second most played instrument, with the first being the piano. A person who makes guitars is called a “luthier”. A person who plays the guitar is called a “guitarist”. Guitarists play the guitar by plucking or strumming the strings with their fingers, fingernails, or a pick. There are several types of guitars: Classical, Electric, Steel, Flamenco, 12 String and many more. It was the classical guitar, also known as the Spanish guitar that had a special presence at the Leo Carrillo Ranch. Music played on the Spanish guitar reminded Leo Carrillo of his family history and was very much a part of the life he experienced as a child growing up. The word guitar was adopted into English from the Spanish word “guitarra” in the 1600’s. The country of Spain has had an extraordinary impact on the development of the classical guitar. Spaniards in Andalusia during the 1790’s took the guitar to new heights when they added a sixth string to it. -

Aloh a Drea M

oohhaa AAll aamm DDrree September 2009 Vol. 7. Issue 3. Contents 1. Lava Tube Beach Moon” by Ben Saber 2. Contents Page 3. Welcome. The Editor’s usual flummoxed verbiage 4. The Chanos International Steel Guitar Festival 5. “ “ “ “ “ “ 6. “ “ “ “ “ “ 7. “ “ “ “ “ “ 8. European Steel Guitar Hall of Fame The Medal” 9. “ “ “ “ “ “ “ 10. Brecon - 16th Hawaiian Guitarsts’ Convention and Luau by Beryl Lavinia 11. “ “ Pictures 12. “ “ Pictures 13. Steelin’ Tricks of the Trade / The Conspiracy 14. Tablature - Sweet Georgia Brown 15. “ “ “ “ 16. Pedal Steel in Hawaiian Music 17. Malcolm Rockwell - A ‘phone interview 18. “ “ “ “ “ “ “ “ 19. “ “ “ “ “ “ “ “ 20. 21. The Steel Guitar in Early Country Music by Anthony Lis: Pt 2 Ch 4 section 2 22. “ “ “ “ “ “ “ “ “ “ “ 23. “ “ “ “ “ “ “ “ “ “ “ 24. “ “ “ “ “ “ “ “ “ “ “ 25. Penny Points to Paradise” By John Marsden 26. Readers Letters 27. “ “ 28. Birthday Bash Shustoke Sailng Club All ads and enquires to :- Editorial and design:- Pat and Basil Henriques Honorary members Pat Henrick Subscriptions:- Pat Jones (Wales.) Morgan & Thorne U.K. £16:00 per year 28-30 The Square Keith Grant (Japan) Europe 25:00€ Aldridge ----------------------------- Overseas $35:00 Walsall WS9 8QS Hawaiian Musicologists (U.S. dollars or equivalent) West Midlands. John Marsden (U.K.) All include P+P (S+H) Phone No:- 0182 770 4110. Prof. Anthony Lis E Mail - [email protected] Payment by UK cheque, cash or web page www.waikiki-islanders.com money order payable to:- Pat Henrick” Published in the U.K. by Waikiki Islanders Aloha Dream Magazine Copyright 2009 2 AAlloohhaa ttoo yyoouu aallll Well here we are late again, I did think of combining this issue with December’s it’s that late. -

A-List Electric Guitarist

A-LIST ELECTRIC GUITARIST - POP CHORDS 2.0 OPERATION MANUAL The information in this document is subject to change without notice and does not represent a commitment on the part of Propellerhead Software AB. The software described herein is subject to a License Agreement and may not be copied to any other media except as specifically allowed in the License Agreement. No part of this publication may be copied, reproduced or otherwise transmitted or recorded, for any purpose, without prior written permission by Propellerhead Software AB. ©2016 Propellerhead Software and its licensors. All specifications subject to change without notice. Reason, Reason Essentials and Rack Extension are trademarks of Propellerhead Software. All other commercial symbols are protected trademarks and trade names of their respective holders. All rights reserved. A-List Electric Guitarist - Pop Chords 2.0 Introduction Electric Guitarist - Pop Chords is the third Rack Extension instrument in the A-List series for Propellerhead Reason and Reason Essentials - after Acoustic Guitarist and Electric Guitarist "Power Chords". Think of Electric Guitarist - Pop Chords as a professional session guitarist, playing electric rhythm guitar on a top-notch instrument hooked up to hand-selected vintage amps and cabinets, and performing exactly as you wish, while giving you full control over musical performance and mix. Whether you want to add realistic rhythm guitar tracks to your productions, use it as an inspiration for writing songs on a train or plane, or as source material for creative sound design - it will get you from idea to result as fast as possible. At the core of Electric Guitarist - Pop Chords - and all instruments in the Propellerhead A-List series - is the idea that you can create professional sounding instrument tracks exactly the way you would get them from an A-List player in the studio. -

Music-Theory-For-Guitar-4.9.Pdf

Music Theory for Guitar By: Catherine Schmidt-Jones Music Theory for Guitar By: Catherine Schmidt-Jones Online: < http://cnx.org/content/col12060/1.4/ > This selection and arrangement of content as a collection is copyrighted by Catherine Schmidt-Jones. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Collection structure revised: September 18, 2016 PDF generated: August 7, 2020 For copyright and attribution information for the modules contained in this collection, see p. 73. Table of Contents 1 Learning by Doing: An Introduction ............................................................1 2 Music Theory for Guitar: Course Introduction ................................................7 3 Theory for Guitar 1: Repetition in Music and the Guitar as a Rhythm Instrument ...................................................................................15 4 Theory for Guitar 2: Melodic Phrases and Chord Changes .................................23 5 Theory for Guitar 3: Form in Guitar Music ...................................................31 6 Theory for Guitar 4: Functional Harmony and Chord Progressions ........................37 7 Theory for Guitar 5: Major Chords in Major Keys ..........................................41 8 Theory for Guitar 6: Changing Key by Transposing Chords ................................53 9 Theory for Guitar 7: Minor Chords in Major Keys ..........................................59 10 Theory for Guitar 8: An Introduction to Chord Function in Minor Keys -

The 50 Greatest Rhythm Guitarists 12/25/11 9:25 AM

GuitarPlayer: The 50 Greatest Rhythm Guitarists 12/25/11 9:25 AM | Sign-In | GO HOME NEWS ARTISTS LESSONS GEAR VIDEO COMMUNITY SUBSCRIBE The 50 Greatest Rhythm Guitarists Darrin Fox Tweet 1 Share Like 21 print ShareThis rss It’s pretty simple really: Whatever style of music you play— if your rhythm stinks, you stink. And deserving or not, guitarists have a reputation for having less-than-perfect time. But it’s not as if perfect meter makes you a perfect rhythm player. There’s something else. Something elusive. A swing, a feel, or a groove—you know it when you hear it, or feel it. Each player on this list has “it,” regardless of genre, and if there’s one lesson all of these players espouse it’s never take rhythm for granted. Ever. Deciding who made the list was not easy, however. In fact, at times it seemed downright impossible. What was eventually agreed upon was Hey Jazz Guy, October that the players included had to have a visceral impact on the music via 2011 their rhythm chops. Good riffs alone weren’t enough. An artist’s influence The Bluesy Beauty of Bent was also factored in, as many players on this list single-handedly Unisons changed the course of music with their guitar and a groove. As this list David Grissom’s Badass proves, rhythm guitar encompasses a multitude of musical disciplines. Bends There isn’t one “right” way to play rhythm, but there is one truism: If it feels good, it is good. The Fabulous Fretwork of Jon Herington David Grissom’s Awesome Open Strings Chuck Berry I don"t believe it A little trick for guitar chords on mandolin MERRY, MERRY Steve Howe is having a Chuck Berry changed the rhythmic landscape of popular music forever. -

Alexander Technique and Body Mapping for Guitarists Alma Sehic University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2014 The onscC ious Guitarist: Alexander Technique and Body Mapping for Guitarists Alma Sehic University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Sehic, A.(2014). The Conscious Guitarist: Alexander Technique and Body Mapping for Guitarists. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3570 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CONSCIOUS GUITARIST: ALEXANDER TECHNIQUE AND BODY MAPPING FOR GUITARISTS by Alma Sehic Bachelor of Arts William Carey College, 2006 Master of Music Appalachian State University, 2008 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2014 Accepted by: Christopher Berg, Major Professor Laury Christie, Committee Member Rebecca Hunter, Committee Member Robert Jesselson, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Alma Sehic, 2014 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to acknowledge the USC SPARC (Support to Promote Research and Creativity) Fellowship—for awarding funds to my project: Body Mapping for Guitarists. The project is featured under the body mapping chapters (chapters 4–8). As a trainee in Body Mapping, I would like to acknowledge the Andover Educators’ (AE) training sources used in this dissertation. These are the AE training manuals (based on the book and related course: What Every Musician Needs to Know About the Body by Barbara Conable); and William Conable’s images (anatomical charts) from the same book—available to trainees and licensed Andover Educators only. -

Guitar in Oxford Music Online

Oxford Music Online Grove Music Online Guitar article url: http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com:80/subscriber/article/grove/music/43006 Guitar (Fr. guitare; Ger. Gitarre; It. chitarra; Sp. guitarra; Port.viola; Brazilian Port. violão). A string instrument of the lute family, plucked or strummed, and normally with frets along the fingerboard. It is difficult to define precisely what features distinguish guitars from other members of the lute family, because the name ‘guitar’ has been applied to instruments exhibiting a wide variation in morphology and performing practice. The modern classical guitar has six strings, a wooden resonating chamber with incurved sidewalls and a flat back. Although its earlier history includes periods of neglect as far as art music is concerned, it has always been an instrument of popular appeal, and has become an internationally established concert instrument endowed with an increasing repertory. In the Hornbostel and Sachs classification system the guitar is a ‘composite chordophone’ of the lute type (seeLUTE, §1, andCHORDOPHONE). 1. Structure of the modern guitar. Fig.1 shows the parts of the modern classical guitar. In instruments of the highest quality these have traditionally been made of carefully selected woods: the back and sidewalls of Brazilian rosewood, the neck cedar and the fingerboard ebony; the face or table, acoustically the most important part of the instrument, is of spruce, selected for its resilience, resonance and grain (closeness of grain is considered important, and a good table will have a grain count about 5 or 6 per cm). The table and back are each composed of two symmetrical sections, as is the total circumference of the sidewalls. -

SESSION GUITARIST - STRUMMED ACOUSTIC - Manual - 4 Welcome to STRUMMED ACOUSTIC

MANUAL Disclaimer The information in this document is subject to change without notice and does not represent a commitment on the part of Native Instruments GmbH. The software described by this docu- ment is subject to a License Agreement and may not be copied to other media. No part of this publication may be copied, reproduced or otherwise transmitted or recorded, for any purpose, without prior written permission by Native Instruments GmbH, hereinafter referred to as Native Instruments. “Native Instruments”, “NI” and associated logos are (registered) trademarks of Native Instru- ments GmbH. Mac, macOS, GarageBand, Logic, iTunes and iPod are registered trademarks of Apple Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries. Windows, Windows Vista and DirectSound are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the United States and/or other countries. All other trade marks are the property of their respective owners and use of them does not im- ply any affiliation with or endorsement by them. Document authored by: Daniel Scholz, Samuel Dalferth Software version: 1.1 (01/2017) Special thanks to the Beta Test Team, who were invaluable not just in tracking down bugs, but in making this a better product. Contact NATIVE INSTRUMENTS GmbH Schlesische Str. 29-30 D-10997 Berlin Germany www.native-instruments.de NATIVE INSTRUMENTS North America, Inc. 6725 Sunset Boulevard 5th Floor Los Angeles, CA 90028 USA www.native-instruments.com NATIVE INSTRUMENTS K.K. YO Building 3F Jingumae 6-7-15, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo 150-0001 Japan www.native-instruments.co.jp NATIVE INSTRUMENTS UK Limited 18 Phipp Street London EC2A 4NU UK www.native-instruments.co.uk © NATIVE INSTRUMENTS GmbH, 2017. -

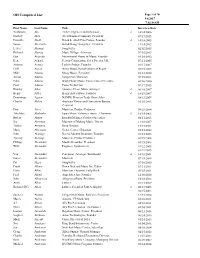

OH Completed List

OH Completed List Page 1 of 70 9/6/2017 7:02:48AM First Name Last Name Title Interview Date Yoshiharu Abe TEAC, Engineer and Innovator d 10/14/2006 Norbert Abel Abel Hammer Company, President 07/17/2015 David L. Abell David L. Abell Fine Pianos, Founder d 10/18/2005 Susan Aberbach Hill & Range Songs Inc., President 11/14/2012 Lester Abrams Songwriter 02/02/2015 Richard Abreau Music Village, Advocate 07/03/2013 Gus Acevedo International House of Music, Founder 01/20/2012 Ken Achard Peavey Corporation, Sales Director UK 07/11/2005 Antonio Acosta Luthier Strings, Founder 01/17/2007 Cliff Acred Amro Music, Band Instrument Repair 07/15/2013 Mike Adams Moog Music, President 01/13/2010 Arthur Adams Songwriter, Musician 09/25/2011 Edna Adams World Wide Music, Former Sales Executive 04/16/2010 Paul Adams Piano Technician 07/17/2015 Hawley Ades Shawnee Press, Music Arranger d 06/10/2007 Henry Adler Henry Adler Music, Founder d 10/19/2007 Dominique Agnew NAMM, Director Trade Show Sales 08/13/2009 Charles Ahlers Anaheim Visitor and Convention Bureau, 01/25/2013 President Don Airey Musician, Product Endorser 09/29/2014 Takehiko Akaboshi Japan Music Volunteer Assoc., Chairman d 10/14/2006 Bulent Akbay Istanbul Mehmet, Product Specialist 04/11/2013 Joy Akerman Museum of Making Music, Docent 11/30/2007 Toshio Akiyama Band Director 12/15/2011 Marty Albertson Guitar Center, Chairman 01/21/2012 John Aldridge Not So Modern Drummer, Founder 01/23/2005 Tommy Aldridge Musician, Product Endorser 01/19/2008 Philipp Alexander Musik Alexander, President 03/15/2008 Will Alexander Engineer, Synthesizers 01/22/2005 01/22/2015 Van Alexander Composer, Arranger, Bandleader d 10/18/2001 James Alexander Musician 07/15/2015 Pat Alger Songwriter 07/10/2015 Frank Alkyer Down Beat and Music Inc, Editor 03/31/2011 Davie Allan Musician, Guitarist, Early Rock 09/25/2011 Fred Allard Amp Sales, Inc, Founder 12/08/2010 John Allegrezza Allegrezza Piano, President 10/10/2012 Andy Allen Luthier 07/11/2017 Richard (RC) Allen Luthier, Friend of Paul A. -

Guitarmuseum.Org

The Instrument That Rocked The World STUDY GUIDE FOR THE EXHIBIT Preliminary!!! www.nationalguitarmuseum.org “GUITAR: The Instrument That Rocked The World” 1 Presented by The National GUITAR Museum TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to the Study Guide . 3 Overview . 4 Definition of Chordophone, Brief History . 5 Parts Of A Guitar . 6 Wood Construction Strings Gears Electricity & The Electric Guitar . .14 Body Parts Pickups Amplifiers Preliminary!!! The Inventors . .17 Antonio De Torres Jurado, C.F. Martin It Electrified Orville Gibson, George Beauchamp Paul Bigsby, Leo Fender, Les Paul, Charles Kaman The Entire Historical Guitars Featured In The Exhibit . 20 The Guitar In Art . 21 World. Caravaggio, Vermeer, Rousseau, Benton, Picasso The Interactives In The Exhibit . .30 Student Activities . 36 Drawing Activities (various ages) . 49 Credits . .62 “GUITAR: The Instrument That Rocked The World” 2 Presented by The National GUITAR Museum Introduction to the Study Guide Science plays a significant role in “GUITAR: The Instrument That Rocked The World.” The science inherent in the guitar (and all music) allows students to explore sound and sound generation from within the instrument itself as well as from the perspective of engineers and musicians. The following pages are designed to be used as both a Teacher’s Reference to “GUITAR: The Instrument That Rocked The World” and an education and activity book. Any of the pages herein can be used for classroom presentations and activity, but it is up to the educator to determine the grade appropriate level of each section. For very young students, teachers may want to disseminate the drawing and activities section only, while using other pages as a guide and prep for the exhibit. -

Becoming a Healthier Guitarist: Understanding

BECOMING A HEALTHIER GUITARIST: UNDERSTANDING AND ADDRESSING INJURIES A DISSERTATION IN Music Performance Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS by BRÁULIO BOSI M.M., Oklahoma City University, 2012 B.M.E., Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, 2010 Kansas City, Missouri 2016 BECOMING A HEALTHIER GUITARIST: UNDERSTANDING AND ADDRESSING INJURIES Bráulio Bosi, candidate for the Doctor of Musical Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2016 ABSTRACT The field of performance arts medicine is supplying musicians with alarming statistics regarding their health. Authors give statistics as high as 93% when discussing the injury rate among instrumentalists. As guitar is one of the instruments listed with the highest incidence of playing-related injuries, this work addresses the types of injuries to which musicians, including guitarists, are prone, as well as their causes and treatment. Musicians often tend to neglect proper treatment for playing related injuries, which leads to the conclusion that investing time in prevention methods is the best choice in regards to injuries. The efficacy of common routines for injury prevention such as warming-up, taking breaks, among others, has proven statistically to be successful. Studies show that warm-up routines and periodic breaks from music practice seem to be effective against playing-related injuries; the benefits of stretching, however, remain controversial. Since some of the injuries investigated are preventable to a large extent through technical adjustments, informed suggestions for guitarists are included. Though the solutions presented are not necessarily the only ones available, they are supported by studies in performing arts medicine. -

Buyers Guide Only

guitar school At On Track Music we share our LOVE for music by teaching students how to play guitar using an organized, friendly, and motivating approach that allows them to ENJOY their instrument for a lifetime. Part of meeting that commitment is being sure that students and parents are properly informed about equipment needs for the guitarists at every level, from the entry level beginner to the student who strives to play professionally. Our staff is instructed to give honest, straight forward advise on what types of equipment will best suit your individual needs. They are not commissioned sales persons and will never try to sell you anything that you do not need. Certain staff members are more knowledgeable about equipment than others, that is one reason that I, Scott Graves, devised this buying guide to help students and parents in purchasing decisions. If you have specific questions about any kind of gear, please ask your teacher or the office person, if they are unsure how to answer your question, they may contact me or one of the other staff members who is knowledgeable in that specific area. Before you make a final decision on your purchase... Here are some things that you should keep in mind about On Track Music and the buying process in general. You should never pay the listed retail price for a guitar. All reputable music instrument dealers are prepared to offer a discount amount that is substantially lower than the list price on most guitars and amps that they sell. Discounted percentages vary from retailer to retailer but tend to be at least 20% below the listed retail price of the instrument.