An Oxford College and the Eighteenth-Century Gothic Revival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Total Work of Art in European Modernism Series Editor: Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Cornell University

The Total Work of Art in European Modernism Series editor: Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Cornell University Signale: Modern German Letters, Cultures, and Thought publishes new English- language books in literary studies, criticism, cultural studies, and intellectual history pertaining to the German-speaking world, as well as translations of im- portant German-language works. Signale construes “modern” in the broadest terms: the series covers topics ranging from the early modern period to the present. Signale books are published under a joint imprint of Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library in electronic and print formats. Please see http://signale.cornell.edu/. The Total Work of Art in European Modernism David Roberts A Signale Book Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library Ithaca, New York Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library gratefully acknowledge the support of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for the publication of this volume. Copyright © 2011 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writ- ing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2011 by Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roberts, David, 1937– The total work of art in European modernism / David Roberts. p. cm. — (Signale : modern German letters, cultures, and thought) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5023-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Modernism (Aesthetics) 2. -

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD Christ Church was founded in 1546, and there had been a college here since 1525, but prior to the Dissolution of the monasteries, the site was occupied by a priory dedicated to the memory of St Frideswide, the patron saint of both university and city. St Frideswide, a noble Saxon lady, founded a nunnery for herself as head and for twelve more noble virgin ladies sometime towards the end of the seventh century. She was, however, pursued by Algar, prince of Leicester, for her hand in marriage. She refused his frequent approaches which became more and more desperate. Frideswide and her ladies, forewarned miraculously of yet another attempt by Algar, fled up river to hide. She stayed away some years, settling at Binsey, where she performed healing miracles. On returning to Oxford, Frideswide found that Algar was as persistent as ever, laying siege to the town in order to capture his bride. Frideswide called down blindness on Algar who eventually repented of his ways, and left Frideswide to her devotions. Frideswide died in about 737, and was canonised in 1480. Long before this, though, pilgrims came to her shrine in the priory church which was now populated by Augustinian canons. Nothing remains of Frideswide’s nunnery, and little - just a few stones - of the Saxon church but the cathedral and the buildings around the cloister are the oldest on the site. Her story is pictured in cartoon form by Burne-Jones in one of the windows in the cathedral. One of the gifts made to the priory was the meadow between Christ Church and the Thames and Cherwell rivers; Lady Montacute gave the land to maintain her chantry which lay in the Lady Chapel close to St Frideswide’s shrine. -

Pevsner's Architectural Glossary

Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 1 PEVSNER’S ARCHITECTURAL GLOSSARY Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 2 Nikolaus and Lola Pevsner, Hampton Court, in the gardens by Wren's east front, probably c. Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 3 PEVSNER’S ARCHITECTURAL GLOSSARY Yale University Press New Haven and London Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 4 Temple Street, New Haven Bedford Square, London www.pevsner.co.uk www.lookingatbuildings.org.uk www.yalebooks.co.uk www.yalebooks.com for Published by Yale University Press Copyright © Yale University, Printed by T.J. International, Padstow Set in Monotype Plantin All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections and of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 5 CONTENTS GLOSSARY Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 6 FOREWORD The first volumes of Nikolaus Pevsner’s Buildings of England series appeared in .The intention was to make available, county by county, a comprehensive guide to the notable architecture of every period from prehistory to the present day. Building types, details and other features that would not necessarily be familiar to the general reader were explained in a compact glossary, which in the first editions extended to some terms. -

Gothic Beyond Architecture: Manchester’S Collegiate Church

Gothic beyond Architecture: Manchester’s Collegiate Church My previous posts for Visit Manchester have concentrated exclusively upon buildings. In the medieval period—the time when the Gothic style developed in buildings such as the basilica of Saint-Denis on the outskirts of Paris, Île-de-France (Figs 1–2), under the direction of Abbot Suger (1081–1151)—the style was known as either simply ‘new’, or opus francigenum (literally translates as ‘French work’). The style became known as Gothic in the sixteenth century because certain high-profile figures in the Italian Renaissance railed against the architecture and connected what they perceived to be its crude forms with the Goths that sacked Rome and ‘destroyed’ Classical architecture. During the nineteenth century, critics applied Gothic to more than architecture; they located all types of art under the Gothic label. This broad application of the term wasn’t especially helpful and it is no-longer used. Gothic design, nevertheless, was applied to more than architecture in the medieval period. Applied arts, such as furniture and metalwork, were influenced by, and followed and incorporated the decorative and ornament aspects of Gothic architecture. This post assesses the range of influences that Gothic had upon furniture, in particular by exploring Manchester Cathedral’s woodwork, some of which are the most important examples of surviving medieval woodwork in the North of England. Manchester Cathedral, formerly the Collegiate Church of the City (Fig.3), see here, was ascribed Cathedral status in 1847, and it is grade I listed (Historic England listing number 1218041, see here). It is medieval in foundation, with parts dating to between c.1422 and 1520, however it was restored and rebuilt numerous times in the nineteenth century, and it was notably hit by a shell during WWII; the shell failed to explode. -

The Church Militant: the American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92

The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Peter Walker All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker This dissertation is a study of the loyalist Church of England clergy in the American Revolution. By reconstructing the experience and identity of this largely-misunderstood group, it sheds light on the relationship between church and empire, the role of religious pluralism and toleration in the American Revolution, the dynamics of loyalist politics, and the religious impact of the American Revolution on Britain. It is based primarily on the loyalist clergy’s own correspondence and writings, the records of the American Loyalist Claims Commission, and the archives of the SPG (the Church of England’s missionary arm). The study focuses on the New England and Mid-Atlantic colonies, where Anglicans formed a religious minority and where their clergy were overwhelmingly loyalist. It begins with the founding of the SPG in 1701 and its first forays into America. It then examines the state of religious pluralism and toleration in New England, the polarising contest over the proposed creation of an American bishop after the Seven Years’ War, and the role of the loyalist clergy in the Revolutionary War itself, focusing particularly on conflicts occasioned by the Anglican liturgy and Book of Common Prayer. -

Pick of the Churches

Pick of the Churches The East of England is famous for its superb collection of churches. They are one of the nation's great treasures. Introduction There are hundreds of churches in the region. Every village has one, some villages have two, and sometimes a lonely church in a field is the only indication that a village existed there at all. Many of these churches have foundations going right back to the dawn of Christianity, during the four centuries of Roman occupation from AD43. Each would claim to be the best - and indeed, all have one or many splendid and redeeming features, from ornate gilt encrusted screens to an ancient font. The history of England is accurately reflected in our churches - if only as a tantalising glimpse of the really creative years between the 1100's to the 1400's. From these years, come the four great features which are particularly associated with the region. - Round Towers - unique and distinctive, they evolved in the 11th C. due to the lack and supply of large local building stone. - Hammerbeam Roofs - wide, brave and ornate, and sometimes strewn with angels. Just lay on the floor and look up! - Flint Flushwork - beautiful patterns made by splitting flints to expose a hard, shiny surface, and then setting them in the wall. Often it is used to decorate towers, porches and parapets. - Seven Sacrament Fonts - ancient and splendid, with each panel illustrating in turn Baptism, Confirmation, Mass, Penance, Extreme Unction, Ordination and Matrimony. Bedfordshire Ampthill - tomb of Richard Nicholls (first governor of Long Island USA), including cannonball which killed him. -

The Arts and Crafts Movement: Exchanges Between Greece and Britain (1876-1930)

The Arts and Crafts Movement: exchanges between Greece and Britain (1876-1930) M.Phil thesis Mary Greensted University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Contents Introduction 1 1. The Arts and Crafts Movement: from Britain to continental 11 Europe 2. Arts and Crafts travels to Greece 27 3 Byzantine architecture and two British Arts and Crafts 45 architects in Greece 4. Byzantine influence in the architectural and design work 69 of Barnsley and Schultz 5. Collections of Greek embroideries in England and their 102 impact on the British Arts and Crafts Movement 6. Craft workshops in Greece, 1880-1930 125 Conclusion 146 Bibliography 153 Acknowledgements 162 The Arts and Crafts Movement: exchanges between Greece and Britain (1876-1930) Introduction As a museum curator I have been involved in research around the Arts and Crafts Movement for exhibitions and publications since 1976. I have become both aware of and interested in the links between the Movement and Greece and have relished the opportunity to research these in more depth. It has not been possible to undertake a complete survey of Arts and Crafts activity in Greece in this thesis due to both limitations of time and word constraints. -

Michael Jackson's Gesamtkunstwerk

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 11, No. 5 (November 2015) Michael Jackson’s Gesamtkunstwerk: Artistic Interrelation, Immersion, and Interactivity From the Studio to the Stadium Sylvia J. Martin Michael Jackson produced art in its most total sense. Throughout his forty-year career Jackson merged art forms, melded genres and styles, and promoted an ethos of unity in his work. Jackson’s mastery of combined song and dance is generally acknowledged as the hallmark of his performance. Scholars have not- ed Jackson’s place in the lengthy soul tradition of enmeshed movement and mu- sic (Mercer 39; Neal 2012) with musicologist Jacqueline Warwick describing Jackson as “embodied musicality” (Warwick 249). Jackson’s colleagues have also attested that even when off-stage and off-camera, singing and dancing were frequently inseparable for Jackson. James Ingram, co-songwriter of the Thriller album hit “PYT,” was astonished when he observed Jackson burst into dance moves while recording that song, since in Ingram’s studio experience singers typically conserve their breath for recording (Smiley). Similarly, Bruce Swedien, Jackson’s longtime studio recording engineer, told National Public Radio, “Re- cording [with Jackson] was never a static event. We used to record with the lights out in the studio, and I had him on my drum platform. Michael would dance on that as he did the vocals” (Swedien ix-x). Surveying his life-long body of work, Jackson’s creative capacities, in fact, encompassed acting, directing, producing, staging, and design as well as lyri- cism, music composition, dance, and choreography—and many of these across genres (Brackett 2012). -

THE MUSEUM During 1970 and 1971 Considerable Work Has Been Done on the Collections, Although Much Still Remains to Be Sorted Out

THE MUSEUM During 1970 and 1971 considerable work has been done on the collections, although much still remains to be sorted out. The work of identifying and labelling geological specimens has been completed, and the insect collections sorted, fumi- gated, labelled, put in checklist order and card indexed. The egg collection has also been re-labelled and card indexed, and some specimens added to it. In the historical field a large collection of photographic plates, mainly taken by Taunt of Oxford about 1900, has been sorted and placed in individual envelopes. Racking has been installed in part of the first floor of the stable and most of the collection of pottery sherds transferred to it, where it is easily accessible. A start has been made on the production of a card index of the folk collection and to-date some 1,500 cards have been completed. At short notice reports on archaeological sites in the Chilterns and in the River Ouse Green Belt were prepared, and at greater leisure one on the Vale of Aylesbury for the County Planning Department. This involved visiting a very large number of sites, which did however yield additional information about some. A start has been made on an examination of air photographs of the county, and a number of new sites, particularly of ring ditches and medieval sites, have been found. Excavations were carried out by the museum staff on four sites referred to in The Records, three of them on behalf of the Milton Keynes Research Committee. Amongst the exhibitions was one of Museum Purchases 1960-1970, opened by Earl Howe, Chairman of the County Education Committee, which showed all the purchases made during that period. -

WORKING PAPERS in LANGUAGE and LITERATURE

Cardiff School of English, Communication and Philosophy Ysgol Saesneg, Cyfathrebu ac Athroniath Caerdydd WORKING PAPERS in LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE Melanie Bigold ‘Collecting, Cataloguing and Losing Women Writers: George Ballard’s Memoirs of Several Ladies’ http://orca.cf.ac.uk/id/eprint/52393 Cardiff University, 2013 Dr Melanie Bigold Cardiff University Collecting, Cataloguing and Losing Women Writers: George Ballard’s Memoirs of Several Ladies I know not how it hath happened that very many ingenious Women of this Nation, who were really possessed of a great share of learning, and have no doubt in their time been famous for it, are but little known not only unknown to the publick in general, and ^ but have ^been passed by in silence, even by our most indefatigable Biographers themselves.1 I know not how it has happened that very many ingenious women of this nation, who were really possessed of a great share of learning and have, no doubt, in their time been famous for it, are not only unknown to the public in general, but have been passed by in silence by our greatest biographers.2 Over fifteen years in the making, George Ballard’s Memoirs of Several Ladies of Great Britain who have been celebrated for their writings or skill in the learned languages, arts and sciences (1752) featured the lives of sixty-four British women from the fourteenth through to the early eighteenth century, making it the most expansive list of learned British women to date.3 However, as Ballard himself was fully aware, his collection was far from complete and he hoped that his ‘imperfect attempt’ might ‘excite some more able Person to carry on and finish the work.’4 The incompleteness of scholarly projects is a familiar trope in the annals of literary history. -

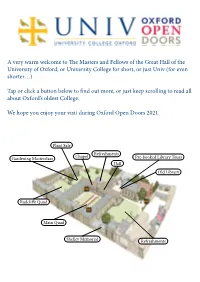

A Very Warm Welcome to the Masters and Fellows of the Great Hall of the University of Oxford, Or University College for Short, Or Just Univ (For Even Shorter…)

A very warm welcome to The Masters and Fellows of the Great Hall of the University of Oxford, or University College for short, or just Univ (for even shorter…) Tap or click a button below to find out more, or just keep scrolling to read all about Oxford’s oldest College. We hope you enjoy your visit during Oxford Open Doors 2021. Plant Sale Refreshments Gardening Masterclass Chapel Pre-booked Library Tours Hall Old Library Radcliffe Quad Main Quad Shelley Memorial Refreshments main quad Once Univ began to accept undergraduates in larger numbers, our medieval Quad was no longer large enough to accommodate everyone comfortably. In 1631, an Old Member called Sir Simon Bennet died, leaving the College a large sum of money, and it was possible to start afresh with a new Quad designed by Richard Maude. Its foundation stone laid on 17 April 1634. The West range was built first because we did not need to demolish any of the existing structures, and was finished in 1635, with work then starting on the North range, facing the High Street, with its tower. This was finished in 1637. In 1639 work began on the South range, with the Hall and the Chapel, but, just as the outer walls were finished in 1642, the English Civil War broke out and all building work stopped. In the 1660s work restarted in earnest. The Chapel was finished in 1666, and then the Kitchen wing to the South of the Quad was started in 1669. Finally in 1675 work started on the last range, on the East. -

Peter Smith, 'Lady Oxford's Alterations at Welbeck Abbey 1741–55', the Georgian Group Journal, Vol. Xi, 2001, Pp

Peter Smith, ‘Lady Oxford’s alterations at Welbeck Abbey 1741–55’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XI, 2001, pp. 133–168 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2001 LADY OXFORD’S ALTERATIONS AT WELBECK ABBEY, – PETER SMITH idowhood could be a rare time of indepen - On July the Duke died unexpectedly, after Wdence for a woman in the eighteenth century, a riding accident at Welbeck, precipitating a and especially for one like the dowager Countess of mammoth legal battle over the Cavendish estates. By Oxford and Mortimer (Fig. ), who had complete his will all his estates in Yorkshire, Staffordshire and control of her own money and estates. Born Lady Northumberland were bequeathed to his year-old Henrietta Cavendish-Holles in , the only daughter Henrietta, while an estate at Orton in daughter of John Holles, st Duke of Newcastle, and Huntingdonshire passed to his wife and the remainder his wife, formerly Lady Margaret Cavendish, she of his considerable property passed to his nephew chose to spend her widowhood building, like her Thomas Pelham. This would have meant that the great-great-great-grandmother, Bess of Hardwick, former Cavendish estates in Nottinghamshire and before her. Derbyshire would have gone to Thomas Pelham, not Lady Oxford had fought hard, and paid a high Henrietta. When the widowed Duchess discovered price, to retain her mother’s Cavendish family estates, the terms of her husband’s will she ‘was indignant and she obviously felt a particularly strong beyond measure’ and ‘immediately resolved to attachment to them. These estates were centred dispute its validity’. The legal battle which ensued around the former Premonstratensian abbey at was bitter and complex, and it was only finally settled Welbeck, in Nottinghamshire, but also included the after the death of the Duchess by a private Act of Bolsover Castle estate in Derbyshire and the Ogle Parliament in .