Informing the Network: Improving Communication with Interface Communities During Wildland Fire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California Fire Siege 2007 an Overview Cover Photos from Top Clockwise: the Santiago Fire Threatens a Development on October 23, 2007

CALIFORNIA FIRE SIEGE 2007 AN OVERVIEW Cover photos from top clockwise: The Santiago Fire threatens a development on October 23, 2007. (Photo credit: Scott Vickers, istockphoto) Image of Harris Fire taken from Ikhana unmanned aircraft on October 24, 2007. (Photo credit: NASA/U.S. Forest Service) A firefighter tries in vain to cool the flames of a wind-whipped blaze. (Photo credit: Dan Elliot) The American Red Cross acted quickly to establish evacuation centers during the siege. (Photo credit: American Red Cross) Opposite Page: Painting of Harris Fire by Kate Dore, based on photo by Wes Schultz. 2 Introductory Statement In October of 2007, a series of large wildfires ignited and burned hundreds of thousands of acres in Southern California. The fires displaced nearly one million residents, destroyed thousands of homes, and sadly took the lives of 10 people. Shortly after the fire siege began, a team was commissioned by CAL FIRE, the U.S. Forest Service and OES to gather data and measure the response from the numerous fire agencies involved. This report is the result of the team’s efforts and is based upon the best available information and all known facts that have been accumulated. In addition to outlining the fire conditions leading up to the 2007 siege, this report presents statistics —including availability of firefighting resources, acreage engaged, and weather conditions—alongside the strategies that were employed by fire commanders to create a complete day-by-day account of the firefighting effort. The ability to protect the lives, property, and natural resources of the residents of California is contingent upon the strength of cooperation and coordination among federal, state and local firefighting agencies. -

2020 Annual Fire Report

Northwest Annual Fire Report 2020 Northwest Interagency Coordination Center Portland, OR Page intentionally left blank TABLE of CONTENTS | NWCC Mission TABLE of CONTENTS TABLE of CONTENTS............................................................................................................... 1 SUMMARY INFORMATION ..................................................................................................... 3 NWCC Mission................................................................................................................................3 NWCC Annual Fire Report General Information ...............................................................................3 NWCC ACCOMPLISHMENTS ................................................................................................... 4 A Review of 2020 ...........................................................................................................................4 Overview ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 NWCC Staff & Organization .................................................................................................................................. 5 Organization: Administration ................................................................................................................................ 5 FIRE SEASON OVERVIEW ..................................................................................................... -

Fire Safety News LAUNCH ALL AIRCRAFT !

Postal Customer PRSRT STD U.S. Postage Escondido, CA 92026 PAID Permit No. 273 Escondido, CA Fire Safety News ECRWSS Serving the communities of Castle Creek, Champagne Village, Deer Springs, West Lilac, Hidden Meadows, Jesmond Dene, Rimrock, and the Welk Resort Volume 5, No. 2 www.DeerSpringsFireSafeCouncil.com Summer, 2008 LAUNCH ALL AIRCRAFT ! CAL FIRE RAMONA AIR ATTACK BASE DURING THE WITCH CREEK FIRE, OCTOBER 2007 The following fire scenario is fictional but could all too easily become a The single digit humidity, high winds, and extremely dry or dead vegetation create reality in our Fire District. It came very close to happening on May 16, 2008 on the ideal conditions for a rapidly moving fire that will threaten lives and property, eastern side of Moosa Canyon. When it does happen, we can all be thankful for the most prominently along the Moosa Canyon Ridge. experience, training, preparation, and discipline of CAL FIRE Air Operations, the CAL FIRE HeliTack Crew Members and the Sheriff’s Office ASTREA Helicop- Within seconds, CAL FIRE Monte Vista dispatches a full response of fire engines, ter pilots who partner with the CAL FIRE personnel in the air and on the ground. water tankers, ground attack crew, and bulldozers. It also orders “LAUNCH These brave men and women put their lives on the line, day in and day out, to save ALL AIRCRAFT” from the San Diego Region. This order sets in to motion a lives and property within our District, the County, and the great State of California. sequence of events that has been anticipated, trained, practiced and performed over We are fortunate to have these resources available to us combined with their strong the course of many years by CAL FIRE Air Operations. -

Review of California Wildfire Evacuations from 2017 to 2019

REVIEW OF CALIFORNIA WILDFIRE EVACUATIONS FROM 2017 TO 2019 STEPHEN WONG, JACQUELYN BROADER, AND SUSAN SHAHEEN, PH.D. MARCH 2020 DOI: 10.7922/G2WW7FVK DOI: 10.7922/G29G5K2R Wong, Broader, Shaheen 2 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. UC-ITS-2019-19-b N/A N/A 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Review of California Wildfire Evacuations from 2017 to 2019 March 2020 6. Performing Organization Code ITS-Berkeley 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report Stephen D. Wong (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3638-3651), No. Jacquelyn C. Broader (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3269-955X), N/A Susan A. Shaheen, Ph.D. (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3350-856X) 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. Institute of Transportation Studies, Berkeley N/A 109 McLaughlin Hall, MC1720 11. Contract or Grant No. Berkeley, CA 94720-1720 UC-ITS-2019-19 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period The University of California Institute of Transportation Studies Covered www.ucits.org Final Report 14. Sponsoring Agency Code UC ITS 15. Supplementary Notes DOI: 10.7922/G29G5K2R 16. Abstract Between 2017 and 2019, California experienced a series of devastating wildfires that together led over one million people to be ordered to evacuate. Due to the speed of many of these wildfires, residents across California found themselves in challenging evacuation situations, often at night and with little time to escape. These evacuations placed considerable stress on public resources and infrastructure for both transportation and sheltering. -

Draft DRECP and EIR/EIS – Appendix R1, Data Supporting Volume

Appendix R1.22 Public Safety and Services This appendix includes 5 tables that present airports, fire stations, police stations, landfills and schools within the Plan Area. Draft DRECP and EIR/EIS APPENDIX R1.22. PUBLIC SAFETY AND SERVICES Appendix R1.22 Public Safety and Services Table R1.22-1 Airports Within and Near the Plan Area Map Key Airport Airport Land use Compatibility Plan 1 Agua Dulce Airpark 2 Apple Valley Town of Apple Valley Airport Comprehensive Land Use Compatibility Plan. Prepared by the Town of Apple Valley. March 1995. 3 Avi Suquilla 4 Banning Municipal 5 Barstow-Daggett Airport Comprehensive Land Use Plan, Barstow-Daggett Airport. San Bernardino County. May 1992. 6 Bermuda Dunes 7 Big Bear City Airport Comprehensive Land Use Plan, Big Bear City Airport. San Bernardino County. February 1992. 8 Bishop 9 Blythe 10 Brawley Airport Land Use Compatibility Plan, Imperial County Airports. Imperial County Airport Land Use Commission. June 1996. 11 Cable Cable Airport Comprehensive Airport Land Use Plan. West Valley Planning Agency Airport Land Use Commission. December 9, 1981. 12 Calexico International Airport Land Use Compatibility Plan, Imperial County Airports. Imperial County Airport Land Use Commission. June 1996. 13 General WM J Fox Airfield 14 Hesperia Comprehensive Land Use Plan, Hesperia Airport. San Bernardino County Airport Land Use Commission. Prepared by Ray A. Vidal Aviation Planning Consultant. January 1991. 15 Imperial County Airport Land Use Compatibility Plan, Imperial County Airports. Imperial County Airport Land Use Commission. June 1996. 16 Inyokern (Kern County) Airport Land Use Compatibility Plan. County of Kern. March 29, 2011. 17 Lake Havasu City 18 Laughlin Bullhead International 19 Mojave (Kern County) Airport Land Use Compatibility Plan. -

Haz Mat Unit Assignments

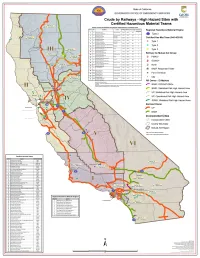

State of California GOVERNOR'S OFFICE OF EMERGENCY SERVICES Cal PES GOVERNOR'S OFFICE OF EMERGENCY SERVICES Crude by Railways - High Hazard Sites with Certified Hazardous Material Teams REGULATIONS GOVERNING RAILROAD OPERATIONS AT DEFINED SITES Site No. RR Site Name County MP Begin MP End Total Length Statistical / Regional Hazardous Material Engine Operational 1 UP Coast Subdivision San Luis Obispo 235.0 249.0 14.0 S (formerly SP Coast Line) Type 2 3 UP Yuma Subdivision San Bernardino/ 535.0 545.0 10.0 S (formerly Yuma Line) Riverside 4 UP Yuma Subdivision Riverside 586.0 592.0 6.0 S Certified Haz-Mat Team (04/14/2016) (formerly Yuma Line) 6 UP Yuma Subdivision San Bernardino/ 542.6 589.0 46.4 0 (formerly Yuma Line) Riverside Type 1 9 UP Black Butte Subdivision Siskiyou 322.1 332.6 10.5 S (formerly Shasta Line, Black Butte District) 10 UP Black Butte Subdivision Siskiyou 322.1 338.5 16.4 0 Type 2 (formerly Shasta Line, Black Butte District) 12 UP Roseville Subdivision Placer 150.0 160.0 10.0 s (formerly Roseville District) Type 3 16 UP Mojave Subdivision Kern 335.0 359.9 24.9 s (formerly Bakers fie Id Line) Refinery by Mutual Aid Group 19 UP Mojave Subdivision San Bernardino 463.0 486.0 23.0 0 (formerly Bakersfield Line) 22 UP Canyon Subdivision Butte 234.0 240.0 6.0 s PMAO (formerly Feather River Division) 23 UP Canyon Subdivision Plumas 253.0 282.0 29.0 s (formerly Feather River Division) SCIMO 25 UP Canyon Subdivision Butte/Plumas 232.1 319.2 87.1 0 (formerly Feather River Division) 26 BNSF Gateway Subdivision Plumas 178.0 188.0 10.0 -

1 Welcome to Santa Monica Mountains

National Park Service Southern California Fire Ecology U.S. Department of the Interior Wildfire Walkabout Santa Monica Mountains High School Teacher Guide National Recreation Area WELCOME Welcome to Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area Southern California Fire Ecology: Wildfire Walkabout The purpose of this guide is to prepare you and your students for your trip to the Santa Monica Mountains. This field trip is self-led. Please read this guide carefully and if you will be visiting, contact the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area (SMMNRA) education team at [email protected]. FIELD TRIP LOCATION The field trip can take place in any recent burn scar in your area or the Santa Monica Mountains. Suggested sites within the park include Paramount Ranch, Rancho Sierra Vista/Satwiwa, Circle X Ranch, Rocky Oaks, Peter Strauss Ranch, or Solstice Canyon. However, you must contact the park to make sure these sites are accessible and available for a field trip by calling (805) 370-2301 or email [email protected]. As this is a teacher-led field trip please feel free to visit any location that is convenient to you that has been affected by a recent wildfire. You may use or modify any of the activities suggested in this program to your needs. DIRECTIONS For directions to the sites above, call (805) 370-2301 or visit https://www.nps.gov/samo/planyourvisit/placestogo.htm GOOD TO KNOW Parking – The parking areas in the national park site locations are free. Other sites in the recreation area may require a fee. National Park Service (NPS) parking lots are open from 8:00 AM to sunset. -

Fire Risk Is Up; Is Rattlesnake Risk Up, Too?

Fire Safety News Serving the communities of Castle Creek, Champagne Village, Deer Springs, West Lilac, Gordon Hill, Hidden Meadows, Jesmond Dene, Rimrock, and the Welk Resort A 501(c)(3) Community Service Organization SEPTEMBER 9, 2014 Ground forces move to the front in the battle against the 32,000-acre Eiler Fire, one of several fires to strike Northern California this summer. / Photo, Jeff Hall, CAL FIRE VIP Photographer Inside This Issue Forward this issue to a friend Parched Brush Intensifies Fire Risk Rattlesnakes Invading Deer Springs? Well, Maybe Not Drought Advice: Be Careful Out There Have you heard (or seen) ... Helpful Phone Numbers Parched Brush Intensifies Fire Risk As California firefighters chase blazes from the Oregon to the Mexico borders, fear grows that Southern California is on the verge of a catastrophic fire. San Diego County has already experienced an unprecedented event this year — Santa Ana wind-driven fires in the month of May. “Santa Ana winds have started many fires that historically have resulted in the loss of many lives and structures in San Diego County,” said CAL FIRE Battalion Chief Nick Schuler, who is based in Deer Springs. But the fires that struck North San Diego County in May struck with surprising ferocity. “This was the first time that we’ve seen a fire in a coastal community that moved so rapidly,” Schuler said of the Poinsettia Fire, which hit Carlsbad on May 14. “Within minutes of the fire breaking out, homes were threatened and self-evacuations were occurring. The magnitude of the fire was alarming.” Six hundred acres of tinder-dry brush burned in Carlsbad in a matter of hours, destroying five single-family residences, 18 apartment units and a large commercial building, and damaging other structures. -

2021 California Mobilization Guide

2021 2021 California Mobilization Guide Table of Contents Chapter 10 – Objectives, Policy, Scope of Operations and Administration ....................................................1 Mission Statement ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographic Area Coordination Center ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Unit Level .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Incident Priorities ............................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Initial Attack ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Immediate Need ................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Drawdown for Initial Attack (IA) ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Mobilization/ -

Fire Management Today Is Published by the Forest Service of the U.S

Fire today ManagementVolume 75 • No. 2 • 2017 RIM FIRE EFFECTS ON RESTORED AREAS BUDWORM EFFECTS AND WILDFIRE YOU WILL NOT STAND ALONE AND MORE … United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Follow us at <https://twitter.com/forestservice> or <http://bi.ly/1kl3Dhz>. USDA Forest Service Like us at <http://on.fb.me/1zN6OQq>. Fire Management Today is published by the Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC. The Secretary of Agriculture has determined that the publication of this periodical is necessary in the transaction of the public business as required by law of this Department. Fire Management Today is available on the world wide web at <http://www.fs.fed.us/fire/fmt/index.html>. Sonny Perdue, Secretary Kaari Carpenter, General Manager U.S. Department of Agriculture Hutch Brown, Editor Tony Tooke, Chief Forest Service Shawna A. Legarza, Psy.D., Director Fire and Aviation Management In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. -

1 First Responders Local Jurisdictions Alameda County Fire Department

First Responders Local Jurisdictions Alameda County Fire Department Alameda County Operational Area Alameda City Fire Department Alderpoint Volunteer Fire Department Alhambra Fire Department Altaville-Melones Fire Protection District Amador Fire Protection District American Canyon Fire Protection District Anaheim Fire & Rescue Anderson Valley Fire Department Angels Camp Fire Department Antelope Valley Fire Protection District Apple Valley Fire Protection District Aptos/La Selva Fire Protection District Arcadia Fire Department Atascadero Fire and Emergency Services Auburn Volunteer Fire Department Bakersfield Fire Department Barona Fire Protection District Barstow Fire Protection District Beckwourth Fire Protection District Benicia Fire Department Berkeley Fire Department Beverly Hills Fire Department Bishop Volunteer Fire Department Bodega Bay Fire Protection District Boulder Creek Fire Protection District Brea Fire Department Burbank Fire Department Calaveras Consolidated Fire Protection District Calaveras County Operational Area Camp Roberts Fire Department Carlsbad Fire Department Carpinteria/Summerland Fire Protection District Cathedral City Fire Department Cazadero Community Service District Central County Fire Department Central Fire Protection District of Santa Cruz County Central Marin Fire Authority Chester Fire Protection District Chico Fire Department 1 Chino Valley Fire District Chula Vista Fire Department Clements Rural Fire Protection District Cloverdale Fire Protection District Clovis Fire Department Colusa Fire Department -

Hill and Woolsey Fire After Action Summary Report

Hill & Woolsey Fires After Action Summary Report 11/13/19 INCIDENT SUMMARY From November 7 to November 22, 2018, Thousand Oaks was engaged in a mass shooting and two fires. This is an After-Action Summary Report (AASR) of three incidents that occurred over a 72-hour period. This AASR includes a three-day response timeline (page 4). This document also includes observations, recommendations for improvements and follow-up items that have been completed or will soon be completed. It is also important to note that this is a summary description of the more formal report that the city submitted to the Ventura County Sheriff Office of Emergency Services. Also included in this report is the EOC structure on page 14, a Hill/Woolsey Fire Boundary map and a Fire History map on page 16. See Attachment 1 – Fire Boundary Map 2 | Page City of Thousand Oaks After Action Report November 13, 2019 SHELTERING MULTI-AGENCY COORDINATION In past incidents, local shelter functions were fully assumed by the American Red Cross (ARC), but during this incident, the ARC representatives were not able to address all local sheltering needs, due to road closures and the resource requests in Los Angeles County. As a result, the City, Conejo Recreation and Park District (CRPD) and the Conejo Valley Unified School District (CVUSD) worked together to establish, staff, and fulfill all the local shelter needs in Thousand Oaks. One of the follow-up items from the incident is to update sheltering procedures between local agencies and to establish a countywide care and shelter plan.