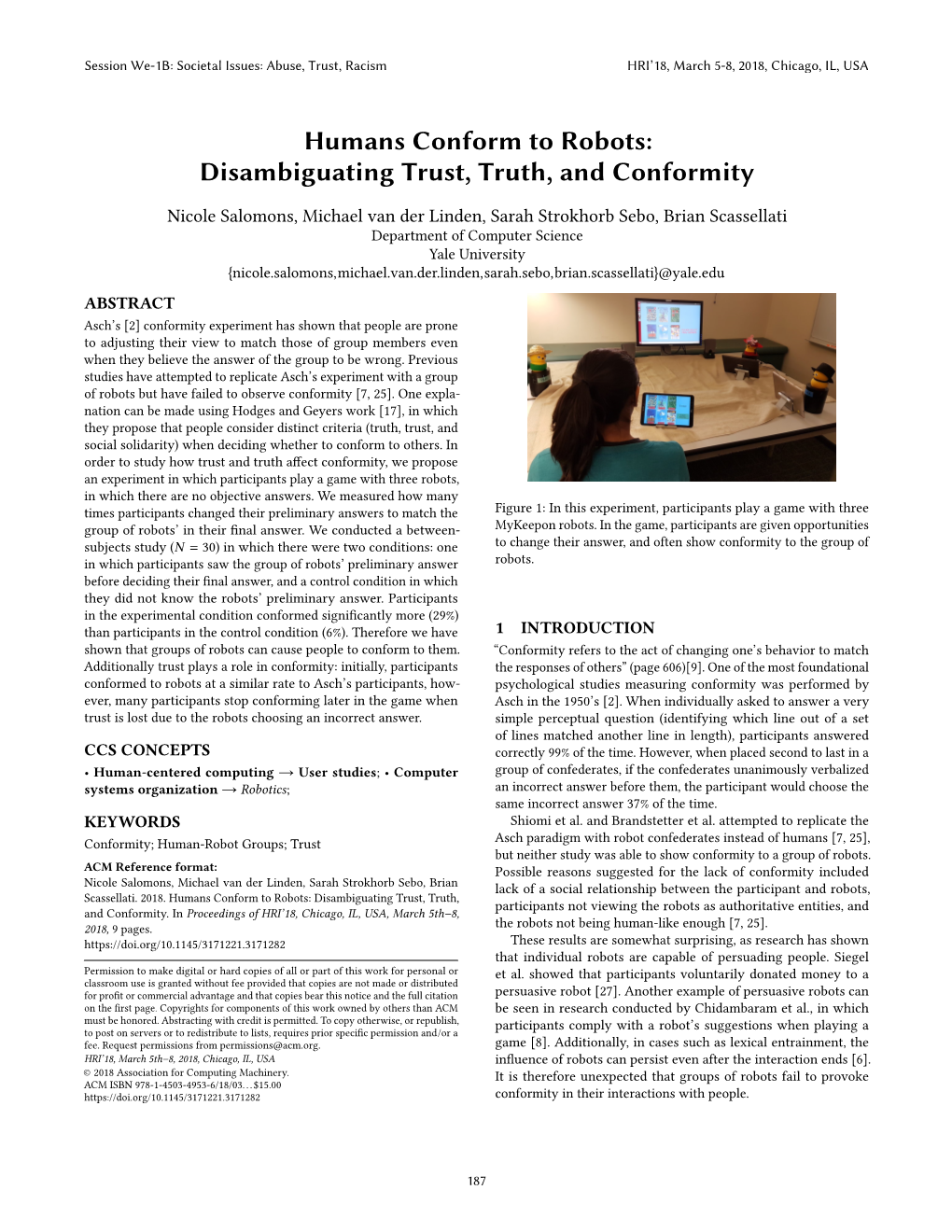

Humans Conform to Robots: Disambiguating Trust, Truth, and Conformity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Theoretical Analysis of ISIS Indoctrination and Recruitment

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 12-2016 A Theoretical Analysis of ISIS Indoctrination and Recruitment Trevor Hawkins California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all Part of the Other Political Science Commons, Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Other Sociology Commons, Political Theory Commons, Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, Social Psychology Commons, and the Theory and Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Hawkins, Trevor, "A Theoretical Analysis of ISIS Indoctrination and Recruitment" (2016). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 7. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all/7 This Capstone Project (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects and Master's Theses at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: ISIS RECRUITMENT A Theoretical Analysis of ISIS Indoctrination and Recruitment Tactics Trevor W. Hawkins California State University of Monterey Bay SBS: 402 Capstone II Professor Juan Jose Gutiérrez, Ph.d. Professor Gerald Shenk, Ph.d. Professor Jennifer Lucido, M.A. December 2016 ISIS RECRUITMENT 2 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Theoretical Framework 6 Influence Psychology 6 Cult Indoctrination 7 Soviet Montage Theory 7 Methodology 8 Execution of Cult Indoctrination Paradigm 9 Execution of Soviet Montage Paradigm 9 Use of Analysis Technology 10 Literature Review 10 I. The Production of Reality Objective Reality 10 Moral Reality 12 Reality of the Self 13 Moral Reality in Context 14 Objective Reality in Context 15 As Context Becomes Reality 16 II. -

Chapter 20: Attitudes and Social Influence

Psychology Journal Write a definition of prejudice in your journal, and list four examples of prejudiced thinking. ■ PSYCHOLOGY Chapter Overview Visit the Understanding Psychology Web site at glencoe.com and click on Chapter 20—Chapter Overviews to preview the chapter. 576 Attitude Formation Reader’s Guide ■ Main Idea Exploring Psychology Our attitudes are the result of condition- ing, observational learning, and cogni- An Attitude of Disbelief tive evaluation. Our attitudes help us On July 20, 1969, Astronaut Neil define ourselves and our place in soci- Armstrong emerged from a space capsule ety, evaluate people and events, and some 250,000 miles from Earth and, while guide our behavior. millions of television viewers watched, ■ Vocabulary became the first man to set foot upon the • attitude moon. Since that time other astronauts • self-concept have experienced that same monumental unique experience in space, yet there are ■ Objectives in existence today numerous relatively • Trace the origin of attitudes. intelligent, otherwise normal humans who • Describe the functions of attitudes. insist it never happened—that the masses have been completely deluded by some weird government hoax—a conspiracy of monumental proportions! There is even a well-publicized organization in England named “The Flat Earth Society,” which seriously challenges with interesting logic all such claims of space travel and evi- dence that the earth is round. —from Story of Attitudes and Emotions by Edgar Cayce, 1972 hat do you accept as fact? What do you call products of fan- tasy? Your attitudes can lead you to believe that something is Wfact when it is really imaginary or that something is not real when it really is fact. -

Does the Planned Obsolescence Influence Consumer Purchase Decison? the Effects of Cognitive Biases: Bandwagon

FUNDAÇÃO GETULIO VARGAS ESCOLA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO DO ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO VIVIANE MONTEIRO DOES THE PLANNED OBSOLESCENCE INFLUENCE CONSUMER PURCHASE DECISON? THE EFFECTS OF COGNITIVE BIASES: BANDWAGON EFFECT, OPTIMISM BIAS AND PRESENT BIAS ON CONSUMER BEHAVIOR. SÃO PAULO 2018 VIVIANE MONTEIRO DOES THE PLANNED OBSOLESCENCE INFLUENCE CONSUMER PURCHASE DECISIONS? THE EFFECTS OF COGNITIVE BIASES: BANDWAGON EFFECT, OPTIMISM BIAS AND PRESENT BIAS ON CONSUMER BEHAVIOR Applied Work presented to Escola de Administraçaõ do Estado de São Paulo, Fundação Getúlio Vargas as a requirement to obtaining the Master Degree in Management. Research Field: Finance and Controlling Advisor: Samy Dana SÃO PAULO 2018 Monteiro, Viviane. Does the planned obsolescence influence consumer purchase decisions? The effects of cognitive biases: bandwagons effect, optimism bias on consumer behavior / Viviane Monteiro. - 2018. 94 f. Orientador: Samy Dana Dissertação (MPGC) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo. 1. Bens de consumo duráveis. 2. Ciclo de vida do produto. 3. Comportamento do consumidor. 4. Consumidores – Atitudes. 5. Processo decisório – Aspectos psicológicos. I. Dana, Samy. II. Dissertação (MPGC) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo. III. Título. CDU 658.89 Ficha catalográfica elaborada por: Isabele Oliveira dos Santos Garcia CRB SP-010191/O Biblioteca Karl A. Boedecker da Fundação Getulio Vargas - SP VIVIANE MONTEIRO DOES THE PLANNED OBSOLESCENCE INFLUENCE CONSUMERS PURCHASE DECISIONS? THE EFFECTS OF COGNITIVE BIASES: BANDWAGON EFFECT, OPTIMISM BIAS AND PRESENT BIAS ON CONSUMER BEHAVIOR. Applied Work presented to Escola de Administração do Estado de São Paulo, of the Getulio Vargas Foundation, as a requirement for obtaining a Master's Degree in Management. Research Field: Finance and Controlling Date of evaluation: 08/06/2018 Examination board: Prof. -

Social Norms and Social Influence Mcdonald and Crandall 149

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Social norms and social influence Rachel I McDonald and Christian S Crandall Psychology has a long history of demonstrating the power and and their imitation is not enough to implicate social reach of social norms; they can hardly be overestimated. To norms. Imitation is common enough in many forms of demonstrate their enduring influence on a broad range of social life — what creates the foundation for culture and society phenomena, we describe two fields where research continues is not the imitation, but the expectation of others for when to highlight the power of social norms: prejudice and energy imitation is appropriate, and when it is not. use. The prejudices that people report map almost perfectly onto what is socially appropriate, likewise, people adjust their A social norm is an expectation about appropriate behav- energy use to be more in line with their neighbors. We review ior that occurs in a group context. Sherif and Sherif [8] say new approaches examining the effects of norms stemming that social norms are ‘formed in group situations and from multiple groups, and utilizing normative referents to shift subsequently serve as standards for the individual’s per- behaviors in social networks. Though the focus of less research ception and judgment when he [sic] is not in the group in recent years, our review highlights the fundamental influence situation. The individual’s major social attitudes are of social norms on social behavior. formed in relation to group norms (pp. 202–203).’ Social norms, or group norms, are ‘regularities in attitudes and Address behavior that characterize a social group and differentiate Department of Psychology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS 66045, it from other social groups’ [9 ] (p. -

Propaganda Fitzmaurice

Propaganda Fitzmaurice Propaganda Katherine Fitzmaurice Brock University Abstract This essay looks at how the definition and use of the word propaganda has evolved throughout history. In particular, it examines how propaganda and education are intrinsically linked, and the implications of such a relationship. Propaganda’s role in education is problematic as on the surface, it appears to serve as a warning against the dangers of propaganda, yet at the same time it disseminates the ideology of a dominant political power through curriculum and practice. Although propaganda can easily permeate our thoughts and actions, critical thinking and awareness can provide the best defense against falling into propaganda’s trap of conformity and ignorance. Keywords: propaganda, education, indoctrination, curriculum, ideology Katherine Fitzmaurice is a Master’s of Education (M.Ed.) student at Brock University. She is currently employed in the private business sector and is a volunteer with several local educational organizations. Her research interests include adult literacy education, issues of access and equity for marginalized adults, and the future and widening of adult education. Email: [email protected] 63 Brock Education Journal, 27(2), 2018 Propaganda Fitzmaurice According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED, 2011) the word propaganda can be traced back to 1621-23, when it first appeared in “Congregatio de progapanda fide,” meaning “congregation for propagating the faith.” This was a mission, commissioned by Pope Gregory XV, to spread the doctrine of the Catholic Church to non-believers. At the time, propaganda was defined as “an organization, scheme, or movement for the propagation of a particular doctrine, practice, etc.” (OED). -

Situational Characteristics and Social Influence: a Conceptual Overview

CAN UNCLASSIFIED Situational characteristics and social influence: A conceptual overview Leandre R. Fabrigar Queen's University Thomas Vaughan-Johnston, Matthew Kan Queen's University Anthony Seaboyer Royal Military College of Canada Prepared by: Queen's University Department of Psychology Kingston, ON K7L 3N6 MOU/MOA: DND RMCC - Service Level Arrangement with Royal Military College of Canada (RMCC) concerning contribution to DRDC's Program Technical Authority: Lianne McLellan, DRDC – Toronto Research Centre Contractor's date of publication: June 2018 Defence Research and Development Canada Contract Report DRDC-RDDC-2018-C121 6HSWHPEHU 2018 CAN UNCLASSIFIED CAN UNCLASSIFIED IMPORTANT INFORMATIVE STATEMENTS This document was reviewed for Controlled Goods by Defence Research and Development Canada (DRDC) using the Schedule to the Defence Production Act. Disclaimer: This document is not published by the Editorial Office of Defence Research and Development Canada, an agency of the Department of National Defence of Canada but is to be catalogued in the Canadian Defence Information System (CANDIS), the national repository for Defence S&T documents. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada (Department of National Defence) makes no representations or warranties, expressed or implied, of any kind whatsoever, and assumes no liability for the accuracy, reliability, completeness, currency or usefulness of any information, product, process or material included in this document. Nothing in this document should be interpreted as an endorsement for the specific use of any tool, technique or process examined in it. Any reliance on, or use of, any information, product, process or material included in this document is at the sole risk of the person so using it or relying on it. -

Getting Beneath the Surface: Scapegoating and the Systems Approach in a Post-Munro World Introduction the Publication of The

Getting beneath the surface: Scapegoating and the Systems Approach in a post-Munro world Introduction The publication of the Munro Review of Child Protection: Final Report (2011) was the culmination of an extensive and expansive consultation process into the current state of child protection practice across the UK. The report focused on the recurrence of serious shortcomings in social work practice and proposed an alternative system-wide shift in perspective to address these entrenched difficulties. Inter-woven throughout the report is concern about the adverse consequences of a pervasive culture of individual blame on professional practice. The report concentrates on the need to address this by reconfiguring the organisational responses to professional errors and shortcomings through the adoption of a ‘systems approach’. Despite the pre-occupation with ‘blame’ within the report there is, surprisingly, at no point an explicit reference to the dynamics and practices of ‘scapegoating’ that are so closely associated with organisational blame cultures. Equally notable is the absence of any recognition of the reasons why the dynamics of individual blame and scapegoating are so difficult to overcome or to ‘resist’. Yet this paper argues that the persistence of scapegoating is a significant impediment to the effective implementation of a systems approach as it risks distorting understanding of what has gone wrong and therefore of how to prevent it in the future. It is hard not to agree wholeheartedly with the good intentions of the developments proposed by Munro, but equally it is imperative that a realistic perspective is retained in relation to the challenges that would be faced in rolling out this new organisational agenda. -

Spiral of Silence and the Iraq War

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 12-1-2008 Spiral of silence and the Iraq war Jessica Drake Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Drake, Jessica, "Spiral of silence and the Iraq war" (2008). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spiral Of Silence And The Iraq War 1 Running Head: SPIRAL OF SILENCE AND THE IRAQ WAR The Rochester Institute of Technology Department of Communication College of Liberal Arts Spiral of Silence, Public Opinion and the Iraq War: Factors Influencing One’s Willingness to Express their Opinion by Jessica Drake A Paper Submitted In partial fulfillment of the Master of Science degree in Communication & Media Technologies Degree Awarded: December 11, 2008 Spiral Of Silence And The Iraq War 2 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Jessica Drake presented on 12/11/2008 ___________________________________________ Bruce A. Austin, Ph.D. Chairman and Professor of Communication Department of Communication Thesis Advisor ___________________________________________ Franz Foltz, Ph.D. Associate Professor Department of Science, Technology and Society/Public Policy Thesis Advisor ___________________________________________ Rudy Pugliese, Ph.D. Professor of Communication Coordinator, Communication & Media Technologies Graduate Degree Program Department of Communication Thesis Advisor Spiral Of Silence And The Iraq War 3 Table of Contents Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………. 5 Project Rationale ………………………………………………………………………………. 8 Review of Literature …………………………………………………………………………. 10 Method ………………………………………………………………………………………... -

SOCIAL INFLUENCE 3.1.1 Social Influence Specification • Types of Conformity: Internalisation, Identification and Compliance

AS PSYCHOLOGY REVISION SOCIAL INFLUENCE 3.1.1 Social influence Specification • Types of conformity: internalisation, identification and compliance. Explanations for conformity: – informational social influence and normative social influence, and variables affecting conformity including group size, unanimity and task difficulty as investigated by Asch. • Conformity to social roles as investigated by Zimbardo. • Explanations for obedience: agentic state and legitimacy of authority, and situational variables affecting obedience including proximity, location and uniform, as investigated by Milgram. • Dispositional explanation for obedience: the Authoritarian Personality. • Explanations of resistance to social influence, including social support and locus of control. • Minority influence including reference to consistency, commitment and flexibility. • The role of social influence processes in social change. TYPES OF CONFORMITY • CONFORMITY – is a form of social influence that results from exposure to the majority position and leads to compliance with that position. It is the tendency for people to adopt the behaviour, attitudes and values of other members of a reference group • COMPLIANCE – occurs when an individual accepts influence because they hope to achieve a favourable reaction from those around them. An attitude or behaviour is adopted not because of its content, but because of the rewards or approval associated with its adoption – Only changes public view, not private TYPES OF CONFORMITY • INTERNALISATION – occurs when an individual -

TUNAP Code of Compliance 2020 Version EN

TUNAP Code of Compliance 2020 Version EN TUNAP works. TUNAP.com »We want performance, predictability, honesty and straightforwardness.« TUNAP Code of Compliance Contents Code of Compliance of the TUNAP GROUP Published by the Central Managing Board of the TUNAP GROUP in February 2020 Applicability 4 I. General Rules of Conduct 5 II. Dealing with Business Partners 9 III. Avoiding Conflicts of Interest 12 IV. Handling Information 14 V. Implementation of the Code of Compliance 16 Your Points of Contact in the TUNAP GROUP 20 3 TUNAP Code of Compliance Applicability This Code of Compliance applies to all TUNAP GROUP employees*. This Code of Compliance sets out rules of conduct for the employees of the TUNAP GROUP. It should be viewed as a guideline and is intended to assist everyone in making decisions in their day-to-day work that conform to both the law and to the TUNAP GROUP’s corporate values. This serves to protect the entire GROUP of com- panies and their employees. The rules contained in this Code of Compliance are binding. If further rules are required due to country-specific factors or differing business models, additional rules can be added to this GROUP-wide Code of Compliance at the company level once they have been approved by the TUNAP GROUP’s Chief Compliance Officer. The general rules of conduct described in this Code of Compliance also apply when dealing with customers as well as for suppliers and other business partners. We expect our business partners to feel obliged to follow these principles as well. Observance of the law, honesty, reliability, respect, and trust comprise the universal foundation of good business relationships. -

Social Influence: Obedience & Compliance Classic Studies

Social Influence: Obedience & Compliance Psy 240; Fall 2006 Purdue University Dr. Kipling Williams Classic Studies • Milgram’s obedience experiments Psy 240: Williams 2 1 What Breeds Obedience? • Escalating Commitment • Emotional distance of the victim • Closeness and legitimacy of the authority • Institutional authority • The liberating effects of group influence © Stanley Milgram, 1965, From the film Obedience, distributed by the Pennsylvania State University Psy 240: Williams 3 Reflections on the Classic Studies • Behavior and attitudes • The power of the situation • The fundamental attribution error Psy 240: Williams 4 2 Social Impact Theory Latané, 1980 Multiplication Division Psy 240: Williams 5 SocialSocial InfluenceInfluence Have I got a deal for you… 3 Defining Social Influence • People affecting other people. • Conformity: Do what others are doing (without the others trying to get you to do it!) • Social inhibition: Stopping doing something you’d normally do because others are present. • Compliance: Getting you to do something you wouldn’t have done otherwise • Obedience: Ordering others to behave in ways they might not ordinarily do • Excellent book and reference: – Cialdini, R. (1996). Influence (4th edition). HarperCollins College Publishers. Psy 240: Williams 7 Weapons of influence Useful metaphors… • Click, Whirr… – these weapons work best on us when we are on “auto-pilot” - not processing the message carefully. • Jujitsu – Compliance professionals get you to do their work for them…they provide the leverage, you do the work Psy 240: Williams 8 4 Six weapons of influence • Reciprocity • Commitment and consistency • Social proof • Liking • Authority • Scarcity Psy 240: Williams 9 Weapon #1: Reciprocity Free hot dogs and balloons for the little ones! • The not-so-free sample • Reciprocal concessions (“door-in-the-face”) large request first (to which everyone would say “no”) followed by the target request. -

11 Social Influence

9781405124003_4_011.qxd 10/31/07 3:09 PM Page 216 Social Influence 11 Miles Hewstone and Robin Martin KEY CONCEPTS autokinetic effect compliance consistency conversion deindividuation door-in-the-face technique evaluation apprehension foot-in-the-door technique group polarization groupthink informational influence lowballing technique majority influence (conformity) minority influence (innovation) norms normative influence obedience to authority referent informational influence self-categorization theory social comparison social facilitation social influence whistleblowing 9781405124003_4_011.qxd 10/31/07 3:09 PM Page 217 CHAPTER OUTLINE This chapter considers two main types of social influence, both of which can be understood in terms of fundamental motives. First, we discuss ‘incidental’ social influence, where people are influenced by the presence or implied presence of others, although there has been no explicit attempt to influence them. We consider the impact of the mere presence of other people on task performance, and the impact of social norms. In the second part of the chapter, we ask why people succumb to social influence, highlighting types of social influence and motives underlying influence on the part of the target of influence. In the third part of the chapter, we turn to ‘deliberate’ social influence. We introduce theory and research on compliance, the influence of numerical majorities and minorities, group decision-making and obedience. Throughout we will see that social influence is an ambivalent concept. On the one hand, it is the glue of society: it makes things work, and society would be utterly chaotic without it. But on the other hand it can be a dark force, underlying some of the most extreme, even immoral, forms of human social behaviour.