Numerals and Language Contact: Albanian, Slavic, and Romani Victor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Shared Lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic

THE SHARED LEXICON OF BALTIC, SLAVIC AND GERMANIC VINCENT F. VAN DER HEIJDEN ******** Thesis for the Master Comparative Indo-European Linguistics under supervision of prof.dr. A.M. Lubotsky Universiteit Leiden, 2018 Table of contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Background topics 3 2.1. Non-lexical similarities between Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2. The Prehistory of Balto-Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2.1. Northwestern Indo-European 3 2.2.2. The Origins of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 4 2.3. Possible substrates in Balto-Slavic and Germanic 6 2.3.1. Hunter-gatherer languages 6 2.3.2. Neolithic languages 7 2.3.3. The Corded Ware culture 7 2.3.4. Temematic 7 2.3.5. Uralic 9 2.4. Recapitulation 9 3. The shared lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 11 3.1. Forms that belong to the shared lexicon 11 3.1.1. Baltic-Slavic-Germanic forms 11 3.1.2. Baltic-Germanic forms 19 3.1.3. Slavic-Germanic forms 24 3.2. Forms that do not belong to the shared lexicon 27 3.2.1. Indo-European forms 27 3.2.2. Forms restricted to Europe 32 3.2.3. Possible Germanic borrowings into Baltic and Slavic 40 3.2.4. Uncertain forms and invalid comparisons 42 4. Analysis 48 4.1. Morphology of the forms 49 4.2. Semantics of the forms 49 4.2.1. Natural terms 49 4.2.2. Cultural terms 50 4.3. Origin of the forms 52 5. Conclusion 54 Abbreviations 56 Bibliography 57 1 1. -

University of Groningen an Acoustic Analysis of Vowel Pronunciation In

University of Groningen An Acoustic Analysis of Vowel Pronunciation in Swedish Dialects Leinonen, Therese IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2010 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Leinonen, T. (2010). An Acoustic Analysis of Vowel Pronunciation in Swedish Dialects. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 01-10-2021 Chapter 2 Background In this chapter the linguistic and theoretical background for the thesis is presented. -

Preaspiration in the Nordic Languages Synchronic and Diachronic Aspects

Preaspiration in the Nordic Languages Synchronic and diachronic aspects Pétur Helgason PhD dissertation Department of Linguistics Stockholm University November 2002 Preaspiration in the Nordic Languages Synchronic and diachronic aspects Pétur Helgason PhD dissertation Stockholm University Department of Linguistics November 2002 PhD dissertation November 2002 Department of Linguistics Stockholm University 106 91 Stockholm Sweden © Pétur Helgason ISBN 91–7265–535–6 Cover Design: Christine Ericsdotter and Pétur Helgason. Front cover map: Evropa Recens Descripta by Guiliemo (Willem) Blaeu, 1649. Back cover map: Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis, by Frederik De Wit, 1660. Printed by Akademitryck AB, Edsbruk 2002 Abstract Preaspiration—the production of glottal friction at the juncture of a vowel and a consonant—appears to be typologically rare but is an areal lin- guistic feature of Northwestern Europe. This study contains a survey of the known geographical spread of preaspirated stops, their phonological distribution and phonetic expressions in some Nordic dialects. The study also suggests a reconstruction of the phonetics of the Proto-Nordic stop contrasts based on synchronic data as well as a more general framework of historical sound change. Following an introduction (Chapter 1), Chapter 2 deals with the definition and typology of preaspiration presenting a global overview of the known geographical spread of preaspiration. The apparent rarity of preaspiration is considered. Proposed, perceptually based explanations of this rarity are evaluated. Chapter 3 offers a fairly detailed account of the known areal spread of pre- aspiration in Europe. Stop systems of several dialects in which preaspira- tion occurs are analysed in terms of voicing conditions. These analyses are based mainly on descriptions provided in the dialectological literature. -

ARAMAIC-LIKE FEATURES in the PENTATEUCH Gary A. Rendsburg As Is Well Known, a Major Trend Has Been Noticeable in the Field of Bi

ARAMAIC-LIKE FEATURES IN THE PENTATEUCH Gary A. Rendsburg Rutgers University The term “Aramaic-like features” is to be distinguished from the term “Aramaisms.” The former refers to linguistic traits found in pre-exilic texts, whose presence can be explained by one of two reasons: either the texts are northern in origin, or the settings of the texts have an Aramean flavor. The lat- ter refers to those features, found primarily in the post-exilic corpus, which re- flect clear Aramaic influence over Hebrew. Aramaic-like features occur with a significant concentration in five sections of the Torah: Genesis 24, Genesis 30–31, Numbers 22–24, Genesis 49, and Deuteronomy 33. Style-switching explains the first three texts, since the first two are narratives geographically set in Aram, while the third portrays a prophet from Aram in the plains of Moab. Regional dialectology explains the remaining two sections: the sayings about the individual tribes must originate in those specific locations, which is why one finds words like MOwrD;d, MRrR…g, and so forth, in the blessings to Issachar, Naphtali, Joseph, and Gad. If the Pentateuch were the product of Persian- period Jewish scribes, as claimed by some scholars during the last several decades, one would expect Aramaisms or Aramaic-like features to appear throughout its 187 chapters in significant concentrations, and not, as per the main conclusion of this essay, in select chapters for specific purposes. As is well known, a major trend has been noticeable in the field of bibli- cal studies during the past twenty years or so. -

The Romance Plural Isogloss and Linguistic Change: a Comparative Study of Romance Nouns Nicola Lampitelli

The Romance plural isogloss and linguistic change: A comparative study of Romance nouns Nicola Lampitelli To cite this version: Nicola Lampitelli. The Romance plural isogloss and linguistic change: A comparative study of Ro- mance nouns. Lingua, Elsevier, 2014, 140, pp.158-179. 10.1016/j.lingua.2013.12.011. hal-00967551 HAL Id: hal-00967551 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00967551 Submitted on 29 Mar 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Appeared in Lingua, 140: 158-179 The Romance Plural Isogloss and Linguistic Change A Comparative Study of Romance Nouns Nicola Lampitelli, Université de Tours ([email protected]) Abstract Romance nouns show a well-known morphological isogloss. There are two groups of languages: those pluralizing by suffixing -s (such as Spanish), and those pluralizing by changing the quality of the final vowel (such as Italian). In this paper, I propose an explanation of this isogloss. More precisely, I argue that the cross-linguistic diversity within Romance depends on morpho-phonological parameters on the structure of the noun. These parameters consist of language-particular restrictions on the form of the (nominal) roots and the exponents of gender and number. -

The Annals of UVAN, VOLUME XV 1981-1983, NUMBER 39-40

THE ANNALS OF THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., INC. VOLUME XV 1981-1983NUMBER 39-40 STUDIES IN UKRAINIAN LINGUISTICS IN HONOR OF GEORGE Y. SHEVELOV EDITED BY JACOB P. HURSKY STUDIES IN UKRAINIAN LINGUISTICS George Y. Shevelov THE ANNALS OF THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., INC. VOLUME XV 1981-1983 NUMBER 39-40 STUDIES IN UKRAINIAN LINGUISTICS in honor of GEORGE Y. SHEVELOV Edited by JACOB P. HURSKY Published by THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U. S., Inc. The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. are published by the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S., Inc. a d v iso r y COMMITTEE: Oleksander Ohloblyn, Past President o f the Ukrain ian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S.; John Fizer, Rutgers University; Omeljan Pritsak, Harvard University; John S. Reshetar, Jr., University of Washington; Ihor Sevčenko, Harvard University. c o m m ittee on publications: George Y. Shevelov, President of the Academy, 1979 to date; Yaroslav Bilinsky, University of Delaware; Lubov Drashevska; Oleh S. Fedyshyn, Staten Island College CUNY; Jacob P. Hursky, Syracuse University; I. S. Koropeckyj, Temple Uni versity; William Omelchenko, Hunter College CUNY. volum e e d it o r : Jacob P. Hursky, Syracuse University. All correspondence, orders, and remittances should be addressed to The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S., 206 West 100th Street, New York, New York 10025. Price of this volume: $30.00. -

An Introduction to Sociolinguistics LEARNING ABOUT LANGUAGE

An Introduction to Sociolinguistics LEARNING ABOUT LANGUAGE General Editors: Geoffrey Leech & Mick Short, Lancaster University Already published: Analysing Sentences (2nd edition) Noel Burton-Roberts Words and Their Meaning Howard Jackson An Introduction to Phonology Francis Katamba Grammar and Meaning Howard Jackson Realms of Meaning: An Introduction to Semantics Th. R. Hofmann An Introduction to Psycholinguistics Danny D. Steinberg An Introduction to Spoken Interaction Anna-Brita Stenström Watching English Change Laurie Bauer Meaning in Interaction: An Introduction to Pragmatics Jenny Thomas An Introduction to Cognitive Linguistics Friedrich Ungerer and Hans-Jörg Schmid Exploring the Language of Poems, Plays and Prose Mick Short Contemporary Linguistics: An Introduction William O’Grady, Michael Dobrovolsky and Francis Katamba Analysing Sentences Noel Burton-Roberts An Introduction to Natural Language Processing Through Prolog Clive Matthews An Introduction to Child Language Development Susan Foster-Cohen The Sounds of Language: An Introduction to Phonetics Henry Rogers An Introduction to Foreign Language Learning and Teaching Keith Johnson An Introduction to Sociolinguistics (4th edition) Janet Holmes An Introduction to Sociolinguistics Fourth Edition JANET HOLMES First published 1992 by Pearson Education Limited Second edition published 2001 Third edition published 2008 Fourth edition published 2013 Published 2013 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © 1992, 2001, 2008, 2013, Taylor & Francis. The right of Janet Holmes to be identified as author of this Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Dialect Geography Seminar English Dialects, A. Mcintyre 1. Illustrations

Handout 5: Dialect geography • Examples of conclusions that can be drawn from isogloss patterns: Seminar English Dialects , A. McIntyre • Intersecting isoglosses like those in Map 2 are one challenge for the Family Tree Model in which 1. Illustrations of some basic principles of dialect geography regional varieties are treated as distinct entities. If we assume dialect groups ‘Southern English’ and Map 1 : Distribution of (non-)rhotic accents in British Isles, at least in the speech of older people (map from ‘Northern English as distinct ‘branches’ of the English family tree, it is paradoxical that some areas are Hughes/Trudgill 1996:59). more ‘Northern’ w.r.t. one feature, but more ‘Southern’ w.r.t. another feature. Patterns like this speak more for the Wave Model , where different features spread in wave-like fashion (sometimes from different centres) and eventually peter out in different areas. • Isogloss bundle : coincidence of several isoglosses, marks boundaries of major dialect groups or languages. These are often a symptom of (geographical, political, cultural, social) barriers which restrict the progress of innovations. Map 2 : Distribution of rhotic accents compared with isogloss for the vowel in cup, come . (Wardhaugh 2002:136). Map 3 : The Rhenish Fan (Rheinischer Fächer ), Wardhaugh (2002:135). Isoglosses reflecting various subinstances of the High German Consonant Shift ( Hochdeutsche/Zweite Lautverschiebung ) form a bundle, except in the East, where they separate in a fan-like pattern. • Geography and diachronic linguistics: Features found in geographically separate areas (e.g. rhotic areas marked A in Map 1) are likely to be conservative (relics), and not innovations. However, note exceptions to this: o Movement of speakers who use the innovation (e.g. -

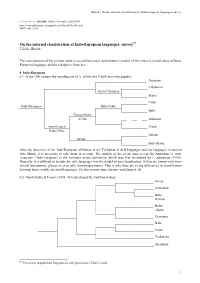

Blažek : on the Internal Classification of Indo-European Languages: Survey

Blažek : On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey Linguistica ONLINE. Added: November 22nd 2005. http://www.phil.muni.cz/linguistica/art/blazek/bla-003.pdf ISSN 1801-5336 On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey[*] Václav Blažek The main purpose of the present study is to confront most representative models of the internal classification of Indo- European languages and their daughter branches. 0. Indo-European 0.1. In the 19th century the tree-diagram of A. Schleicher (1860) was very popular: Germanic Lithuanian Slavo-Lithuaian Slavic Celtic Indo-European Italo-Celtic Italic Graeco-Italo- -Celtic Albanian Aryo-Graeco- Greek Italo-Celtic Iranian Aryan Indo-Aryan After the discovery of the Indo-European affiliation of the Tocharian A & B languages and the languages of ancient Asia Minor, it is necessary to take them in account. The models of the recent time accept the Anatolian vs. non- Anatolian (‘Indo-European’ in the narrower sense) dichotomy, which was first formulated by E. Sturtevant (1942). Naturally, it is difficult to include the relic languages into the model of any classification, if they are known only from several inscriptions, glosses or even only from proper names. That is why there are so big differences in classification between these scantily recorded languages. For this reason some scholars omit them at all. 0.2. Gamkrelidze & Ivanov (1984, 415) developed the traditional ideas: Greek Armenian Indo- Iranian Balto- -Slavic Germanic Italic Celtic Tocharian Anatolian [*] Previously unpublished. Reproduced with permission. [Editor’s note] 1 Blažek : On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: survey 0.3. -

6. the Construction of Isoglosses

6. The construction of isoglosses 6.1. Criteria for selection 3. Differences in the position of phonemes or allophones within a subsystem that are a response to asymmetries created by (2) Dialect geography has traditionally been concerned with the search for a prin- cipled basis for dividing dialects and drawing the boundaries (or isoglosses) All three of these are involved in the chain shifts discussed in Chapter 3. The dis- between them (Bloomfield 1933; Petyt 1980; Chambers and Trudgill 1980; cussion of the principal dialect areas of North America will begin with type (1), Kretzschmar 1992). This section concerns one aspect of this problem: the criteria splits and mergers, since these sound changes will provide the basic motivation used to select the particular variables or boundaries that will serve as the basis for and rationale for the changes of type (2) and (3) that follow. However, the iso- establishing dialects. The following section will deal with methods of defining glosses created by ongoing mergers will not be used to define the major regional the spatial location of these boundaries once the criteria have been established. dialects, since they are driven by Herzogʼs principle to expand across previously All dialect geography begins with the search for geographic differentiation. established frontiers. In fact, one merger that played a central initiating role in the Perhaps the most important consideration in selecting a parameter for dialect massive fronting of back vowels across all of North America has now expanded classification is the degree of spatial differentiation it displays. Any examination to cover almost the entire continent (the merger of /iw/ and /uw/, Map 8.3). -

![[Folia Linguistica] Proto-Germanic Ai In](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2037/folia-linguistica-proto-germanic-ai-in-4432037.webp)

[Folia Linguistica] Proto-Germanic Ai In

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Proto-Germanic ai in North and West Germanic Versloot, A.P. DOI 10.1515/flih-2017-0010 Publication date 2017 Document Version Final published version Published in Folia Linguistica Historica Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Versloot, A. P. (2017). Proto-Germanic ai in North and West Germanic. Folia Linguistica Historica, 51(s38), 281–324. https://doi.org/10.1515/flih-2017-0010 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:25 Sep 2021 Folia Linguistica Historica 2017; 38: 281–324 Arjen P. Versloot* Proto-Germanic ai in North and West Germanic https://doi.org/10.1515/flih-2017-0010 Abstract: Proto-Germanic (PGmc.) ai in stressed syllables shows varied outcomes in Germanic languages (ā, ē,ei), with many of these developments being con- ditioned by different phonological contexts. -

English and German a Comparison of Both Languages

English and German A Comparison of both Languages 1 Introduction The purpose of this presentation is to highlight the major differences in the histories of German and English and so help students better understand how languages which are related and stem from a common ancestor –in this case Germanic –can come to have such diverging forms today. 2 The Germanic Languages 3 4 Like German, English is an Indo- European language. Both belong to the German group of languages found in northern and north- western Europe. You can tell that German and English are genetically related. 5 English is a Germanic language as are German, Dutch, Flemish, Afrikaans, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, Faroese and Icelandic. This means that it belongs to an early grouping of Indo-European which distinguishes itself from other languages of this family by having undergone a series of changes to consonants in initial position. In general, stops become fricatives due to the operation of the Germanic Sound Shift (sometimes also called Grimm’s Law). This is assumed to have taken place many centuries BC. The operation of this law can be recognised by comparing words in Latin with their cognates (etymologically related forms) in English as in the following table. Latin English Old English pes [p] foot [f] fot tres [t] three [þ] þreo collis [k] hill [x] hyl quod [kw] what [xw] hwæt 6 7 8 9 10 11 The History of English 12 Periods in the history of English 0)Runic period, pre-5c 1) Old English (450-1066) 2) Middle English (1066-1500) 3) Early Modern English (1500-1800) 4)Late Modern English (1800-) 13 CeCeltltiicc BBrriittaainin Historical distribution of Celts in Europe 14 TThhee RRoommaannss iinn BBrrititaainin In 55 BC the emperor Julius Caesar invades Britain establishing Roman rule in the south and south-eeaast.