Thesis/Dissertation Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 the Da Vinci Code Dan Brown

The Da Vinci Code By: Dan Brown ISBN: 0767905342 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 CONTENTS Preface to the Paperback Edition vii Introduction xi PART I THE GREAT WAVES OF AMERICAN WEALTH ONE The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries: From Privateersmen to Robber Barons TWO Serious Money: The Three Twentieth-Century Wealth Explosions THREE Millennial Plutographics: American Fortunes 3 47 and Misfortunes at the Turn of the Century zoART II THE ORIGINS, EVOLUTIONS, AND ENGINES OF WEALTH: Government, Global Leadership, and Technology FOUR The World Is Our Oyster: The Transformation of Leading World Economic Powers 171 FIVE Friends in High Places: Government, Political Influence, and Wealth 201 six Technology and the Uncertain Foundations of Anglo-American Wealth 249 0 ix Page 2 Page 3 CHAPTER ONE THE EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES: FROM PRIVATEERSMEN TO ROBBER BARONS The people who own the country ought to govern it. John Jay, first chief justice of the United States, 1787 Many of our rich men have not been content with equal protection and equal benefits , but have besought us to make them richer by act of Congress. -Andrew Jackson, veto of Second Bank charter extension, 1832 Corruption dominates the ballot-box, the Legislatures, the Congress and touches even the ermine of the bench. The fruits of the toil of millions are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few, unprecedented in the history of mankind; and the possessors of these, in turn, despise the Republic and endanger liberty. -

Vicks Vaporub Shows Its Speed

Vicks VapoRub Professor Ron Eccles shows its speed Dr David Hull VICKS VAPORUB SHOWS ITS SPEED Vicks VapoRub (VVR) has been commercially available for over 100 years, as a remedy for congested nasal passages. A study led by Professor Ron Eccles and Dr David Hull has now demonstrated the speed of its effect in common cold sufferers. To begin, what attracted you to this area Dr David Hull: We continue to explore the in the treatment of upper respiratory tract of research? attributes of all products, young and old. infections such as the common cold and Diseases in collaboration with researchers As ideas, and sometimes new methods flu. Since science came to understand the MEASURING HOW RAPIDLY at the Common Cold and Nasal Research Professor Ron Eccles: During my modular emerge, we strive to bring this to bear by receptor biochemistry of these substances, Centre at Cardiff University, focussed on zoology undergraduate course at Liverpool gathering an improved understanding of the exploration of their effects has been the speed of action of VVR, compared to University, I chose to do a module in their effects. We knew that VapoRub was more easily explained. Also as we now VICKS VAPORUB EXERTS ITS a petrolatum control using a group of 50 pharmacology. I found the investigation fast-acting (just open the jar and you can feel have a receptor-based pharmacology for common-cold sufferers. Cold and flu sufferers of how drugs work in humans an amazing an effect), but we had not tried to quantify aromatic oils to work with, we can better PHARMACOLOGY report that one of the main desires for any and exciting area of study and decided that before and we did not know if the feeling plan experiments such as this one in the medication is a feeling of rapid relief from to switch my undergraduate studies to extended from just cooling to an actual expectation of an interesting and valuable Researchers at the Common Cold and Nasal Research Centre at Cardiff nasal congestion, as this symptom interferes pharmacology. -

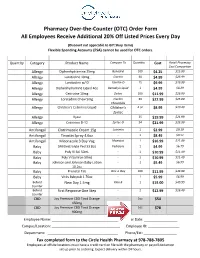

See Our Updated Over-The-Counter Medication Listing Effective May 2020. We Also Have New Lower

Pharmacy Over-the-Counter (OTC) Order Form All Employees Receive Additional 20% Off Listed Prices Every Day (Discount not applicable to Gift Shop items) Flexible Spending Accounts (FSA) cannot be used for OTC orders. Quantity Category Product Name Compare To Quantity Cost Retail Pharmacy Cost Comparison Allergy Diphenhydramine 25mg Benadryl 100 $4.25 $15.99 Allergy Loratadine 10mg Claritin 30 $4.99 $23.99 Allergy Loratadine w/ D Claritin-D 15 $9.99 $19.99 Allergy Diphenhydramine Liquid 4oz Benadryl Liquid 1 $4.99 $8.29 Allergy Cetirizine 10mg Zyrtec 100 $11.99 $26.99 Allergy Loratadine Chew 5mg Claritin 30 $22.99 $25.00 Chewables Allergy Children’s Cetirizine Liquid Children’s 4 oz $8.99 $10.49 Zyrtec Allergy Xyzal 35 $19.99 $21.99 Allergy Cetirizine D-12 Zyrtec-D 24 $21.99 $23.99 Antifungal Clotrimazole Cream 15g Lotrimin 1 $2.99 $9.19 Antifungal Tinactin Spray 4.6oz - 1 $8.49 $9.51 Antifungal Miconazole 3 Day Vag Monistat 1 $16.99 $21.99 Baby SM Electrolyte Ped 33.8oz Pedialyte 1 $4.99 $6.79 Baby Poly Vi Sol 50mL - 1 $10.99 $11.49 Baby Poly Vi Sol Iron 50mL - 1 $10.99 $11.49 Baby Johnson and Johnson Baby Lotion - 1 $5.49 $6.99 10.2oz Baby Prenatal Tab One-a-Day 100 $11.99 $33.99 Baby Vicks Babyrub 1.76oz - 1 $5.99 $6.99 Behind New Day 1.5mg Plan B 1 $15.00 $49.99 Counter Behind First Response One Step - 2 $12.99 $16.49 Counter CBD Joy Premium CBD Tinct Orange - 1oz $54 450mg CBD Joy Premium CBD Tinct Orange - 1oz $78 900mg Employee Name: __________________________________ Order Date: _________________ Campus/Location: ___________________________________ Employee ID: ________________ Department: ____________________________________ Phone/Ext: _________________ Fax completed form to the Circle Health Pharmacy at 978-788-7805 Employees at offsite locations must have a credit card on file with the pharmacy or payroll deduction set up prior to ordering. -

2002 Sustainability Report Executive Summary Linking Opportunity With

2002 Sustainability Report Executive Summary Linking Opportunity with Responsibility Visit http://www.pg.com/sr for the full report. P&G 2002 Sustainability Report Executive Summary A. G. Lafley’s Statement There are two important things to know about Procter & Gamble. and different parts of the world. We are doing this. In several developing countries, we are experimenting to find the best ways First, the consumer is boss. Our business is based on this simple to make beneficial products, such as NutriStar, available to families idea. When we deliver to consumers the benefits we’ve promised, no matter how challenging their economic circumstances may be. when we provide a delightful and memorable usage experience, when we make everyday life a little bit better, a little easier, a little Sustainability challenges are not limited to the developing world, of bit healthier and safer, then we begin to earn the trust on which course. We are also focused on using the same kind of thinking to great brands are built. Sustaining that trust requires an even improve lives and build P&G’s business in developed markets. One greater commitment because improving lives is not a one-time example is our Actonel prescription drug for the treatment and event nor is it a one-dimensional challenge; we must provide prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis, which is already a products and services that meet the needs of consumers around $400 million brand – and growing. Another example is the use of the world while always fulfilling P&G’s responsibilities as a cause-related marketing to build sales of established brands in corporate citizen. -

CANDY: Candy Bar $0.95 Altoids Peppermints $1.00 Breathsavers

Please use this list when ordering items from the Country Store, using the complete description (but not price). No more than 10 individual items can be ordered at one time – e.g. 3 candy bars count as 3 items. Call x2167 the night before you plan to pick up the items. Give your name, UNIT NUMBER, phone extension. Pick-up hours are 1 – 3 PM Monday – Saturday. CANDY: Candy Bar $0.95 Altoids peppermints $1.00 Breathsavers Peppermint $0.85 Breathsavers Spearmints $0.85 Cadbury Bar chocolate $1.95 Dentyne Peppermint gum $1.25 Dentyne Spearmint gum $1.25 Eclipse Polar Ice chewing gum $1.25 Fruit stripe chewing gum $1.25 Lifesavers Five Flavor $0.75 Lindt Lindor Dark chocolate $0.33 Lindt Lindor Milk chocolate $0.33 M&M Peanut chocolate $1.50 Mentos mints $1.00 Tic Tac Fresh Mints $0.95 Toblerone chocolate $2.19 Trident gum $1.25 Wrigley Big Red gum $1.25 Wrigley Juicy Fruit gum $1.25 SNACKS Almonds $3.00 Better Cheddars $3.90 Big Mama $1.28 Bud’s Best Wafers $0.55 Cheez-it $0.80 Chex Mix $0.66 Chips Ahoy $4.40 Chips, regular $1.25 Club crackers $1.80 Page 1 of 13 Fig Newtons $2.30 Gardetto snack mix $2.40 Ginger Snaps $5.08 Lorna Doone cookies $2.00 Nature Valley bar $0.48 Oreo cookies $2.30 Pea Snack Crisps $2.00 Pepperidge Farm cookies $3.89 Pepperidge Farm Goldfish $2.49 Planters, Peanut Pack $0.80 Planters Cashews, can $6.20 Planters cashews, pack $1.50 Planters cocktail peanuts, can $4.25 Planters mixed nuts, can $5.00 Planters unsalted nuts $4.50 Popcorn butter $0.80 Pretzels $1.25 Ritz cheese cracker sandwiches $0.50 Ritz crackers $4.30 -

Proctor & Gamble 11/24

Proctor & Gamble 11/24 $2 off Align Probiotic Supplement, excl trial (exp 12/7) $3/2 Always Radiant, Infinity, or PURE Pads, 10-ct+ (exp 12/28) $1 off Bounty Paper Towel Product, 4-ct+ or 2 Huge Roll (exp 12/7) $1 off Cascade ActionPacs Dishwasher Detergent 20-37 ct (exp 12/7) .50/1 Cascade Dishwasher Detergent, Rinse Aid or Dishwasher Cleaner, excl trial (exp 12/7) $1 off Charmin Toilet Paper Product, 4 Mega-Roll+, incl Mega Plus & Super Mega, excl single rolls (exp 12/7) $5 off Crest 3D White Whitestrips Kit, excl Noticeably White, Classic White, or Original Whitening, Gentle Whitening or Express Whitening kit, and trial (exp 12/7) .50/1 Crest Kids toothpaste, 4.2 oz+ (exp 12/7) $1 off Crest Mouthwash 473 mL or 16 oz+ (exp 12/7) $2 off Crest Toothpaste 3 oz+, excl Cavity, Regular, Baking Soda, Tartar Control/Protection, F&W Pep Gleem, kids (exp 12/7) .75/2 Dawn Scrubbers, Sponges 3 pk+, Brushes amd Fillable Dishwands, excl gloves and liquids (exp 12/22) .50/1 Dawn Ultra Dishwashing Liquid or Platinum Foam, 10.1 oz+, excl special value, Simply Clean and trial (exp 12/7) -$2 off Downy Liquid Fabric Conditioner 72 load+ incl Infusions or WrinkleGuard 40 oz+ or Odor Protect 48 oz+ or Nature Blends 67 oz+, OR Bounce or Downy Sheets 130 ct+ incl Bounce or Downy WrinkleGuard 80 ct+, OR In-Wash Scent Boosters 8.6 oz+ incl Downy Unstopables, Fresh Protect, Odor Protect or Infusions; excl trial, limit 1 (exp 12/28) $1 off Downy Liquid Fabric Conditioner 48-90 load incl Infusions or WrinkleGuard 25 oz or Odor Protect 32 oz or Nature Blends 44 oz, -

OFFICIAL PROGRAM Switch to OVO

FINALS SERIES 4 – 6 May Sydney Olympic Park Aquatic Centre OFFICIAL PROGRAM Switch to OVO OVO MOBILE - XL $ Unlimited talk and text in OZ + 19 GB 24.98 + 500 international mins* / 30 days OVO MOBILE - LARGE $ Unlimited talk and text in OZ + 10 GB 17.98 + 300 international mins* / 30 days OVO MOBILE - MEDIUM $ unlimited talk and text in Oz + 5 GB 14.98 + 50 international mins* / 30 days OVO.com.au Must sign up by May 31, 2018. T&Cs apply. Ongoing price from month 3 will be; OVO Mobile-XL at $49.95; OVO Mobile – Large at $34.95 and OVO Mobile – Medium #ForTheFans at $29.95 *International minutes are to OVO’s 32 most dialled countries, see OVO.com.au/pricing for details. Welcome from the WPA President Welcome to the 2018 Australian Waterpolo League Finals. On behalf of the board of Water Polo Australia I would like to welcome all of the athletes, coaches, referees, volunteers and fans to the culmination of a successful and competitive season of water Polo in Australia. This year’s AWL has seen some wonderfully close competition amongst some of the best athletes in the nation as they battle towards the title in Australia’s premier water polo competition. 2018 marks the 29th season of the AWL and we thank all of the clubs and the WPA team for making this possible. This season has enjoyed some brilliantly innovative events and special round games captured thanks to our wonderful supporters at Ovo Mobile. We are appreciative of all of our sponsors and Club supporters who make the AWL possible and implore the water polo family to support those who support our sport. -

DATE VENUE TIME OPPOSITION FYFE Adelaide Jets (W) FYFE Adelaide Jets (M) FYFE Adelaide Jets (W) FYFE Adelaide Jets (M) Queenslan

DATE VENUE TIME OPPOSITION 4:30PM FYFE Adelaide Jets (W) Sat 25 Jan 2020 Adelaide 6:00PM FYFE Adelaide Jets (M) 10:00AM FYFE Adelaide Jets (W) Sun 26 Jan 2020 Adelaide 11:30AM FYFE Adelaide Jets (M) Auburn Ruth Everuss 7:00PM Queensland Thunder (W) Thu 30 Jan 2020 Aquatic Centre 8:30PM Queensland Thunder (M) Auburn Ruth Everuss 7:00PM Queensland Thunder (W) Fri 31 Jan 2020 Aquatic Centre 8:30PM Queensland Thunder (M) Drummoyne Swimming 6:30PM Drummoyne Devils (W) Sat 08 Feb 2020 Pool 8:00PM Drummoyne Devils (M) Drummoyne Swimming 4:30PM Drummoyne Devils (W) Sun 09 Feb 2020 Pool 6:00PM Drummoyne Devils (M) 7:00PM Sydney Uni Lions (W) Thu 20 Feb 2020 Peter Montgomery Pool 8:30PM Sydney Uni Lions (M) 2:00PM Sydney Uni Lions (W) Sun 23 Feb 2020 Peter Montgomery Pool 3:30PM Sydney Uni Lions (M) Auburn Ruth Everuss 7:00PM UWA Torpedoes (W) Thu 12 Mar 2020 Aquatic Centre 8:30PM UWA Torpedoes (M) Auburn Ruth Everuss 7:00PM Fremantle Marlins (W) Fri 13 Mar 2020 Aquatic Centre 8:30PM Fremantle Mariners (M) Auburn Ruth Everuss TBC UWA Torpedoes (W) Sat 14 Mar 2020 Aquatic Centre TBC UWA Torpedoes (M) 9:30AM Fremantle Marlins (W) Sun 15 Mar 2020 Pymble Ladies College 11:00AM Fremantle Mariners (M) UNSW Fitness and Aquatic 5:00PM UNSW Killer Whales (W) Sat 21 Mar 2020 Centre 6:30PM UNSW Wests Magpies (M) Auburn Ruth Everuss 5:00PM UNSW Killer Whales (W) Sun 22 Mar 2020 Aquatic Centre 6:30PM UNSW Wests Magpies (M) Auburn Ruth Everuss 7:00PM ACU Cronulla Sharks (W) Thu 26 Mar 2020 Aquatic Centre 8:30PM ACU Cronulla Sharks (M) Auburn Ruth Everuss 7:00PM Hunter Hurricanes (W) Fri 27 Mar 2020 Aquatic Centre 8:30PM Hunter Hurricanes (M) Auburn Ruth Everuss 2:30PM Hunter Hurricanes (W) Sat 28 Mar 2020 Aquatic Centre 4:00PM Hunter Hurricanes (M) 11:00AM ACU Cronulla Sharks (W) Sun 29 Mar 2020 Sutherland Leisure Centre 12:30PM ACU Cronulla Sharks (M) 3 - 5 April Sydney Olympic Park FINALS SERIES. -

I Remember It As Early November, During a Trip to Sydney

from the publisher GREG T ROSS remember it as early November, during a trip to Sydney. Like surfing, tennis is an integral part of Australian summers. We But it had been going for some time before that. feature too, in this edition, tennis great Rod Laver’s latest book, Memories blur doing events like the recent bushfires but The Golden Era. it started in northern New South Wales and Queensland. We also look at famous Green Bans activist Jack Mundey and Then it seemed like there was a new fire every day in the book on Jack, by his friend and architect, James Colman. The Idifferent parts of the country. It became the greatest natural book, The House That Jack Built, underpins the knowledge that disaster in Australia’s history. preservation of Australia’s historic regions and buildings is just as It impacted The Last Post. I was in Adelaide putting the 21st important now as it was back then. edition together when I received photos of fires close to my house Writer and filmmaker Jemma Pigott writes for The Last Post with in Long Beach, NSW. I flew home and had to spent two nights her story of indigenous veterans, The Coloured Diggers and Wing in Sydney before the roads south opened long enough for me to Commander Mary Anne Whiting takes us to Point Cook in Victoria return home. I walked into an ordeal of some magnitude. Over for a story on the Rededication of the AFC and RAAF Memorial. the next week or so there were orders to leave, as the fires drew We have too, an update on the amazing work being done by closer. -

The Byron Shire Echo

THE BYRON SHIRE Volume 26 #39 VHYHQ Tuesday, March 13, 2012 Mullumbimby 02 6684 1777 Byron Bay 02 6685 5222 Fax 02 6684 1719 [email protected] [email protected] www.echo.net.au CAB 23,200 copies every week AUDIT I’VE GROWN ACCUSTOMED TO THIS TYPEFACE 3 New Santos Full moon Thursday at boss appointed Luis Feliu Byron’s Main Beach Th e Mullumbimby-based wholefoods retailer Santos has appointed a replace- ment for general manager Jean Bous- sard who resigned suddenly last week. The announcement came in the wake of a fi ery meeting of company staff , owners and management days earlier. Ryan Hamilton, who managed the company’s Byron Bay warehouse for the past 10 years, has been named as interim general manager. Th e Santos board of directors issued a brief statement this week saying Mr Hamilton ‘knows Santos intimately,’ and would replace Mr Boussard im- mediately. Th e board said ‘everybody at Santos is doing their best’ and it was ‘grateful to all staff for their openness and dedication’. During the meeting, Mr Boussard, who was appointed to run the 30-year- old business a year ago, had off ered to stay away from Santos’s three outlets and work from home in an eff ort to ease tensions until a further extraordi- nary meeting was held. But that was not necessary as he re- signed four days aft er the meeting. Th e board in its statement said it More than a thousand people enjoyed the free moonlit screening of the surf movie Minds In The Water on Thursday, as part of the Byron Bay International acknowledged ‘the wonderful support Film Festival. -

The Evolution of Brand Preferences Evidence from Consumer Migration

The Evolution of Brand Preferences Evidence from Consumer Migration Bart J. Bronnenberg Jean-Pierre H. Dubé CentER, Tilburg University University of Chicago and NBER Matthew Gentzkow∗ University of Chicago and NBER First version: April 26, 2010 This version: August 2, 2010 Abstract We study the long-run evolution of brand preferences, using new data on consumers’ life histo- ries and purchases of consumer packaged goods. Variation in where consumers have lived in the past allows us to isolate the causal effect of past experiences on current purchases, holding constant con- temporaneous supply-side factors. We show that brand preferences form endogenously, are highly persistent, and explain 40 percent of geographic variation in market shares. Counterfactuals suggest that brand preferences create large entry barriers and durable advantages for incumbent firms, and can explain the persistence of early-mover advantage over long periods. JEL classification: D12, L1 ∗We thank Aimee Drolet, Jon Guryan, Emir Kamenica, Kevin Murphy, Fiona Scott Morton, Jesse Shapiro, Chad Syver- son, and participants at the INFORMS Marketing Science Conference, in Ann Arbor, Michigan, the 2nd Workshop on the Economics of Advertising and Marketing in Paris, France, and the NBER Summer Institute (IO) for helpful comments. We gratefully acknowledge feedback from seminar participants at the Erasmus University Rotterdam, Goethe University Frank- furt, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, London Business School, Stanford University, Tel-Aviv University, University of California, Los Angeles, the University of Chicago, and Universidade Nova Lissabon. We thank Grace Hy- att and Todd Kaiser at Nielsen for their assistance with the collection of the data, and the Marketing Science Institute, the Neubauer Family Foundation, and the Initiative on Global Markets at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business for financial support. -

9.99 10.99 4.99 4.99 3.99 4.29 5.99 9.99 8.99 2.79 7.99 1.99 2 for $7

THE BRANDS YOU TRUST AT A PRICE YOU’LL LOVE Buy $30 of any of these advertised Procter and Gamble products (tax not included), and get a $10 coupon good on your next visit! Tide Laundry Detergent Metamucil Oral-B Toothbrush Selected varieties 100 oz. to 142 oz. Selected varieties 15 oz. to 30.5 oz. Selected varieties of 9.99 or 100 count Advantage or Stages. SAVE UP TO 6.00 8.99 2 for $4 SAVE UP TO 3.58 on 2 Charmin Ultra Bath Tissue Dawn Dish Soap 12 Mega rolls or 24 Big rolls Selected varieties 19 oz. to 24 oz. Crest Pro•Health Rinse Bounty Paper Towels 2.79 Selected varieties liter Select-A-Size 12 rolls SAVE UP TO 1.46 4.99 10.99 SAVE UP TO 1.90 SAVE UP TO 5.00 Gillette Venus Razor Selected varieties single count Glide Floss Downy Fabric Softener 7.99 Selected varieties Selected varieties SAVE UP TO 4.00 25 to 50 meters 41 oz. to 51 oz. 2.99 4.99 Gillette Satin Care SAVE UP TO 2.00 Selected varieties 7 oz. Tampax or Always 1.99 Selected varieties of Tampax 20 Bounce Fabric Softener Sheets count or Always 14 to 50 count. Selected varieties Pantene Hair Care 2 for $5 120 count Selected var. 6.6 oz. to 16.9 oz. SAVE UP TO 3.38 on 2 4.99 2 for $7 SAVE UP TO 2.00 SAVE UP TO 2.98 on 2 Always Innity Pads Selected varieties 14 to 18 count Cascade Detergent 60 oz.