The Evolution of Brand Preferences Evidence from Consumer Migration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 the Da Vinci Code Dan Brown

The Da Vinci Code By: Dan Brown ISBN: 0767905342 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 CONTENTS Preface to the Paperback Edition vii Introduction xi PART I THE GREAT WAVES OF AMERICAN WEALTH ONE The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries: From Privateersmen to Robber Barons TWO Serious Money: The Three Twentieth-Century Wealth Explosions THREE Millennial Plutographics: American Fortunes 3 47 and Misfortunes at the Turn of the Century zoART II THE ORIGINS, EVOLUTIONS, AND ENGINES OF WEALTH: Government, Global Leadership, and Technology FOUR The World Is Our Oyster: The Transformation of Leading World Economic Powers 171 FIVE Friends in High Places: Government, Political Influence, and Wealth 201 six Technology and the Uncertain Foundations of Anglo-American Wealth 249 0 ix Page 2 Page 3 CHAPTER ONE THE EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES: FROM PRIVATEERSMEN TO ROBBER BARONS The people who own the country ought to govern it. John Jay, first chief justice of the United States, 1787 Many of our rich men have not been content with equal protection and equal benefits , but have besought us to make them richer by act of Congress. -Andrew Jackson, veto of Second Bank charter extension, 1832 Corruption dominates the ballot-box, the Legislatures, the Congress and touches even the ermine of the bench. The fruits of the toil of millions are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few, unprecedented in the history of mankind; and the possessors of these, in turn, despise the Republic and endanger liberty. -

Vicks Vaporub Shows Its Speed

Vicks VapoRub Professor Ron Eccles shows its speed Dr David Hull VICKS VAPORUB SHOWS ITS SPEED Vicks VapoRub (VVR) has been commercially available for over 100 years, as a remedy for congested nasal passages. A study led by Professor Ron Eccles and Dr David Hull has now demonstrated the speed of its effect in common cold sufferers. To begin, what attracted you to this area Dr David Hull: We continue to explore the in the treatment of upper respiratory tract of research? attributes of all products, young and old. infections such as the common cold and Diseases in collaboration with researchers As ideas, and sometimes new methods flu. Since science came to understand the MEASURING HOW RAPIDLY at the Common Cold and Nasal Research Professor Ron Eccles: During my modular emerge, we strive to bring this to bear by receptor biochemistry of these substances, Centre at Cardiff University, focussed on zoology undergraduate course at Liverpool gathering an improved understanding of the exploration of their effects has been the speed of action of VVR, compared to University, I chose to do a module in their effects. We knew that VapoRub was more easily explained. Also as we now VICKS VAPORUB EXERTS ITS a petrolatum control using a group of 50 pharmacology. I found the investigation fast-acting (just open the jar and you can feel have a receptor-based pharmacology for common-cold sufferers. Cold and flu sufferers of how drugs work in humans an amazing an effect), but we had not tried to quantify aromatic oils to work with, we can better PHARMACOLOGY report that one of the main desires for any and exciting area of study and decided that before and we did not know if the feeling plan experiments such as this one in the medication is a feeling of rapid relief from to switch my undergraduate studies to extended from just cooling to an actual expectation of an interesting and valuable Researchers at the Common Cold and Nasal Research Centre at Cardiff nasal congestion, as this symptom interferes pharmacology. -

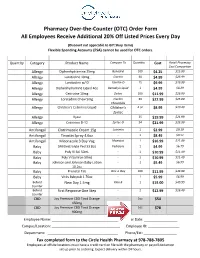

See Our Updated Over-The-Counter Medication Listing Effective May 2020. We Also Have New Lower

Pharmacy Over-the-Counter (OTC) Order Form All Employees Receive Additional 20% Off Listed Prices Every Day (Discount not applicable to Gift Shop items) Flexible Spending Accounts (FSA) cannot be used for OTC orders. Quantity Category Product Name Compare To Quantity Cost Retail Pharmacy Cost Comparison Allergy Diphenhydramine 25mg Benadryl 100 $4.25 $15.99 Allergy Loratadine 10mg Claritin 30 $4.99 $23.99 Allergy Loratadine w/ D Claritin-D 15 $9.99 $19.99 Allergy Diphenhydramine Liquid 4oz Benadryl Liquid 1 $4.99 $8.29 Allergy Cetirizine 10mg Zyrtec 100 $11.99 $26.99 Allergy Loratadine Chew 5mg Claritin 30 $22.99 $25.00 Chewables Allergy Children’s Cetirizine Liquid Children’s 4 oz $8.99 $10.49 Zyrtec Allergy Xyzal 35 $19.99 $21.99 Allergy Cetirizine D-12 Zyrtec-D 24 $21.99 $23.99 Antifungal Clotrimazole Cream 15g Lotrimin 1 $2.99 $9.19 Antifungal Tinactin Spray 4.6oz - 1 $8.49 $9.51 Antifungal Miconazole 3 Day Vag Monistat 1 $16.99 $21.99 Baby SM Electrolyte Ped 33.8oz Pedialyte 1 $4.99 $6.79 Baby Poly Vi Sol 50mL - 1 $10.99 $11.49 Baby Poly Vi Sol Iron 50mL - 1 $10.99 $11.49 Baby Johnson and Johnson Baby Lotion - 1 $5.49 $6.99 10.2oz Baby Prenatal Tab One-a-Day 100 $11.99 $33.99 Baby Vicks Babyrub 1.76oz - 1 $5.99 $6.99 Behind New Day 1.5mg Plan B 1 $15.00 $49.99 Counter Behind First Response One Step - 2 $12.99 $16.49 Counter CBD Joy Premium CBD Tinct Orange - 1oz $54 450mg CBD Joy Premium CBD Tinct Orange - 1oz $78 900mg Employee Name: __________________________________ Order Date: _________________ Campus/Location: ___________________________________ Employee ID: ________________ Department: ____________________________________ Phone/Ext: _________________ Fax completed form to the Circle Health Pharmacy at 978-788-7805 Employees at offsite locations must have a credit card on file with the pharmacy or payroll deduction set up prior to ordering. -

2002 Sustainability Report Executive Summary Linking Opportunity With

2002 Sustainability Report Executive Summary Linking Opportunity with Responsibility Visit http://www.pg.com/sr for the full report. P&G 2002 Sustainability Report Executive Summary A. G. Lafley’s Statement There are two important things to know about Procter & Gamble. and different parts of the world. We are doing this. In several developing countries, we are experimenting to find the best ways First, the consumer is boss. Our business is based on this simple to make beneficial products, such as NutriStar, available to families idea. When we deliver to consumers the benefits we’ve promised, no matter how challenging their economic circumstances may be. when we provide a delightful and memorable usage experience, when we make everyday life a little bit better, a little easier, a little Sustainability challenges are not limited to the developing world, of bit healthier and safer, then we begin to earn the trust on which course. We are also focused on using the same kind of thinking to great brands are built. Sustaining that trust requires an even improve lives and build P&G’s business in developed markets. One greater commitment because improving lives is not a one-time example is our Actonel prescription drug for the treatment and event nor is it a one-dimensional challenge; we must provide prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis, which is already a products and services that meet the needs of consumers around $400 million brand – and growing. Another example is the use of the world while always fulfilling P&G’s responsibilities as a cause-related marketing to build sales of established brands in corporate citizen. -

CANDY: Candy Bar $0.95 Altoids Peppermints $1.00 Breathsavers

Please use this list when ordering items from the Country Store, using the complete description (but not price). No more than 10 individual items can be ordered at one time – e.g. 3 candy bars count as 3 items. Call x2167 the night before you plan to pick up the items. Give your name, UNIT NUMBER, phone extension. Pick-up hours are 1 – 3 PM Monday – Saturday. CANDY: Candy Bar $0.95 Altoids peppermints $1.00 Breathsavers Peppermint $0.85 Breathsavers Spearmints $0.85 Cadbury Bar chocolate $1.95 Dentyne Peppermint gum $1.25 Dentyne Spearmint gum $1.25 Eclipse Polar Ice chewing gum $1.25 Fruit stripe chewing gum $1.25 Lifesavers Five Flavor $0.75 Lindt Lindor Dark chocolate $0.33 Lindt Lindor Milk chocolate $0.33 M&M Peanut chocolate $1.50 Mentos mints $1.00 Tic Tac Fresh Mints $0.95 Toblerone chocolate $2.19 Trident gum $1.25 Wrigley Big Red gum $1.25 Wrigley Juicy Fruit gum $1.25 SNACKS Almonds $3.00 Better Cheddars $3.90 Big Mama $1.28 Bud’s Best Wafers $0.55 Cheez-it $0.80 Chex Mix $0.66 Chips Ahoy $4.40 Chips, regular $1.25 Club crackers $1.80 Page 1 of 13 Fig Newtons $2.30 Gardetto snack mix $2.40 Ginger Snaps $5.08 Lorna Doone cookies $2.00 Nature Valley bar $0.48 Oreo cookies $2.30 Pea Snack Crisps $2.00 Pepperidge Farm cookies $3.89 Pepperidge Farm Goldfish $2.49 Planters, Peanut Pack $0.80 Planters Cashews, can $6.20 Planters cashews, pack $1.50 Planters cocktail peanuts, can $4.25 Planters mixed nuts, can $5.00 Planters unsalted nuts $4.50 Popcorn butter $0.80 Pretzels $1.25 Ritz cheese cracker sandwiches $0.50 Ritz crackers $4.30 -

Proctor & Gamble 11/24

Proctor & Gamble 11/24 $2 off Align Probiotic Supplement, excl trial (exp 12/7) $3/2 Always Radiant, Infinity, or PURE Pads, 10-ct+ (exp 12/28) $1 off Bounty Paper Towel Product, 4-ct+ or 2 Huge Roll (exp 12/7) $1 off Cascade ActionPacs Dishwasher Detergent 20-37 ct (exp 12/7) .50/1 Cascade Dishwasher Detergent, Rinse Aid or Dishwasher Cleaner, excl trial (exp 12/7) $1 off Charmin Toilet Paper Product, 4 Mega-Roll+, incl Mega Plus & Super Mega, excl single rolls (exp 12/7) $5 off Crest 3D White Whitestrips Kit, excl Noticeably White, Classic White, or Original Whitening, Gentle Whitening or Express Whitening kit, and trial (exp 12/7) .50/1 Crest Kids toothpaste, 4.2 oz+ (exp 12/7) $1 off Crest Mouthwash 473 mL or 16 oz+ (exp 12/7) $2 off Crest Toothpaste 3 oz+, excl Cavity, Regular, Baking Soda, Tartar Control/Protection, F&W Pep Gleem, kids (exp 12/7) .75/2 Dawn Scrubbers, Sponges 3 pk+, Brushes amd Fillable Dishwands, excl gloves and liquids (exp 12/22) .50/1 Dawn Ultra Dishwashing Liquid or Platinum Foam, 10.1 oz+, excl special value, Simply Clean and trial (exp 12/7) -$2 off Downy Liquid Fabric Conditioner 72 load+ incl Infusions or WrinkleGuard 40 oz+ or Odor Protect 48 oz+ or Nature Blends 67 oz+, OR Bounce or Downy Sheets 130 ct+ incl Bounce or Downy WrinkleGuard 80 ct+, OR In-Wash Scent Boosters 8.6 oz+ incl Downy Unstopables, Fresh Protect, Odor Protect or Infusions; excl trial, limit 1 (exp 12/28) $1 off Downy Liquid Fabric Conditioner 48-90 load incl Infusions or WrinkleGuard 25 oz or Odor Protect 32 oz or Nature Blends 44 oz, -

9.99 10.99 4.99 4.99 3.99 4.29 5.99 9.99 8.99 2.79 7.99 1.99 2 for $7

THE BRANDS YOU TRUST AT A PRICE YOU’LL LOVE Buy $30 of any of these advertised Procter and Gamble products (tax not included), and get a $10 coupon good on your next visit! Tide Laundry Detergent Metamucil Oral-B Toothbrush Selected varieties 100 oz. to 142 oz. Selected varieties 15 oz. to 30.5 oz. Selected varieties of 9.99 or 100 count Advantage or Stages. SAVE UP TO 6.00 8.99 2 for $4 SAVE UP TO 3.58 on 2 Charmin Ultra Bath Tissue Dawn Dish Soap 12 Mega rolls or 24 Big rolls Selected varieties 19 oz. to 24 oz. Crest Pro•Health Rinse Bounty Paper Towels 2.79 Selected varieties liter Select-A-Size 12 rolls SAVE UP TO 1.46 4.99 10.99 SAVE UP TO 1.90 SAVE UP TO 5.00 Gillette Venus Razor Selected varieties single count Glide Floss Downy Fabric Softener 7.99 Selected varieties Selected varieties SAVE UP TO 4.00 25 to 50 meters 41 oz. to 51 oz. 2.99 4.99 Gillette Satin Care SAVE UP TO 2.00 Selected varieties 7 oz. Tampax or Always 1.99 Selected varieties of Tampax 20 Bounce Fabric Softener Sheets count or Always 14 to 50 count. Selected varieties Pantene Hair Care 2 for $5 120 count Selected var. 6.6 oz. to 16.9 oz. SAVE UP TO 3.38 on 2 4.99 2 for $7 SAVE UP TO 2.00 SAVE UP TO 2.98 on 2 Always Innity Pads Selected varieties 14 to 18 count Cascade Detergent 60 oz. -

50% Free* Free*

DECEMBER 29, 2019 – JANUARY 4, 2020 BUY 1 GET 1 Wet And Wild Cosmetics % • Full Line 50 OFF* Regular $.99 - $8.99 Physician's Formula Cosmetics • Full Line BUY 1 GET 1 Premier Value Regular $4.49 - $16.49 * Vitamins or FREE Supplements Neutrogena Cosmetics • Assorted • Full Line Regular $3.99 - $31.99 Regular $7.49 - $14.99 NEW! 2/ 88 99 THE BIG 3 5 Buy Any New Vicks Charmin DEAL Google Play VapoCool • 6pk Gift Card Cough Drops Regular $7.99 2/$ and • Regular or Severe Bounty Receive • 18ct - 20ct Essentials 5 • Select A Size Hormel up to Regular $2.49 $39 Bonus • 6pk Pepperoni Stick Regular $9.29 • 8oz for Candy Crush Get your NEW YEAR PARTY Started! EVERYDAY 2/$ 5/$ YOUR CHOICE! 99 LOW 5 11 14 PRICES! Arizona Pepsi Iced Tea Products • Assorted • Assorted • 128oz • 16.9oz - 6pk or Regular $3.49 7.5oz - 6pk Plus Deposit Truly Hard Seltzer, White Claw, Arnold Palmer Spiked, Keebler Cape Line Variety or Henry's Hard Variety Crackers • 12oz - 12pk • Plus Deposit • Assorted BUY 1 GET 1 • 9.5oz - 13.8oz EVERYDAY BUY 1 GET 1 YOUR CHOICE! 99 LOW Regular $3.99 * FREE 20 PRICES! FREE Lay's Nature Valley Kellogg's Classic Labatt Blue, Blue Light, Granola Bars Potato Chips • Assorted Cereal Coors Light, Miller Lite, • Assorted • Assorted Molson, Molson 67, • 7.4oz - 8.9oz • 9.5oz - 10oz Regular $3.49 - $3.69 • 10.1oz - 16.6oz Budweiser or Regular $4.99 Regular $4.29 Bud Light • 12oz - 30pk • Plus Deposit EVERYDAY BONUS 99 YOUR CHOICE! 99 LOW PACK! 6 14 PRICES! Maxwell House Blue Moon, Angry Orchard, Sam Adams, Twisted Tea, Coffee Mike's Hard Lemonade, -

VICKS Medicated VAPORUB Drugs Nasal Congestion Reliever

Newly designated quasi- VICKS Medicated VAPORUB drugs Nasal congestion reliever (Newly designated quasi- drugs) Vicks VapoRub alleviates symptoms associated with cold such as nasal congestion and sneezing by applying on the chest, throat and back. Indication Alleviation of symptoms associated with cold such as nasal congestion and sneezing Dosage and administration Apply the following amount on the chest, throat or back, or cover the site with cloth after application (One teaspoonful is approximately 3 g.) 12 years or over: 6 to 10 g per dose, 3 times daily 6 to 11 years: 5 g per dose, 3 times daily 3 to 5 years: 4 g per dose, 3 times daily 6 months to 2 years: 3 g per dose, 3 times daily Under 6 months: Do not use. Comply with the prescribed dosage and administration instructions. When allowing children to use the medicine, a guardian must be present to watch and tell such them how to use it. Attention should be paid so that the medicine will not come into contact with eyes. If the medicine comes into contact with eyes, immediately rinse them with water or lukewarm water. If the symptoms are severe, seek an ophthalmologist for medical treatment. The drug is for external use only. Do not take it orally. ingredient and amount In 100 g dl-Camphor 5.26g Turpentine oil 4.68g l-Menthol 2.82g Eucalyptus oil 1.33g Nutmeg oil 0.69g Cryptomeria japonica leaf oil 0.44g Excipients Thymol ,Petrolatum,, Precautions When not to use the product (If you do not follow these instructions, the current symptoms may worsen or adverse reactions are more likely to occur.) ● The medicine should not be used on the following parts: Skin around the eyes and mucosa (e.g. -

TRIAL: Vapor Rub, Petrolatum and No Treatment for Children with Nocturnal Cough and Cold Symptoms1

RxFiles.ca Trial Summary D. Bunka May 2011 TRIAL: Vapor Rub, Petrolatum and No Treatment for Children with Nocturnal Cough and Cold Symptoms1 Bottom Line: Reassure parents that colds in young children are generally self‐limiting. New evidence suggests that vapor rub (VR) is effective at providing symptomatic relief of nocturnal cough, congestion and sleep difficulties in children > 2 years of age, as compared to petrolatum or no treatment. However, consideration should be give to limitations: duration of study was only 1 night, small population, potential for loss of blinding, funding source (makers of VICKS VAPORUB) and use of subjective parental assessment as the primary outcome. If parents decide to use VR, inform them it is common for children to experience mild irritant effects (~15‐30%) such as burning skin, eyes, and/or nose. Continue to recommend routine comfort measures (e.g. humidifiers, saline nasal spray) for symptomatic relief. Background: The Health Canada restrictions2 for use of OTC cough and cold medications in treating young children, leaves many parents wondering what they can do to help their little one feel better. The Trial: o Partially double‐blinded, randomized, single‐night study design with 138 children, stratified by age mean 5.8 ± 2.8 yrs. o Included: ages 2 to 5 yrs and 6 to 11 years, with URI sx of cough, congestion and rhinorrhea lasting 7 days or longer. o Excluded: hx of asthma, chronic lung disease, or seizure disorder, signs/sx of a more treatable disease (e.g. sinusitis, pneumonia, allergic rhinitis). Excluded if child was given selected OTC or Rx meds on the night before enrollment (e.g. -

Japan's in World

[i' (T V m t^ y PA6BS) SOUTHjMANCHBSTOR, f BBRUARY 17i 1933. *0 :j ▼OL. LH« NO. 119. (caaMUtod AdvarOsteff fm ASSASSIN H ^D BY MIAMI AOTHORITIES JAPAN’ S IN WORLD Makes rr^ DOLLAR DAY For Settfiif HERE TOMORROW D is^ e But Japan R ioses State labor Leader Says ToAcc^Tkem. Extra Fme Vataes Offered Towns Witheot Hearing About a For Snpreme Bargain Geneva. Feb. 17.—(AP)— Lees ,thaa an hour after tbe League of As R a M Is Bronght Forward Under Nations had transmitted to all the EraitoftheYear. Bri^eport, :^ b . 17.-7-(.AP)—John vnorld’s government a its report and J., Egan, secretary'; of * toe State Federation .of Labor today called at Has Nodiing To Say--€on$tiw pf Victmis; recommendations on the Manchurian Tomorrow is Dollar-Day and Man <ji8pute todays Tosuke Matsuo^ chester merchants are offering ex tention to toe possibilities of relief the Japanese spokesman, said «his traordinary ^ values. With depres "for unemployment to be found in the- "^Satisfactory” — government would not awcept theim sion prices in effect the event is be Federal Emergency Relief and Con He dtfended preparations fof in-J ing .called, “The Bargain Event Su- struction Act of 1932 as analyzed Special Train. vasion of the Provinco of Jehol, as pteme.” by toe American Federation of serting that Japan will fight if she Labor. has to, but ho evaded questions Dollar Day offers values that will Egan said toe Federation, from provide buyers with ' merchandise Miami; Fla., Feb. 17-—(A P)—*1116; * vioTiBis’ GoFi>nibi»li^ ' 2 about the possibility of his gbvem- statistics it had compiled estimated Dade County Medical Assoriation , CALLED ment’s withdrawal from the League. -

2 Jan. 2013--A Cold Sunny Day, of the Kind C and I Have Lamented a Shortage of in Recent Jlblolx Tines, at This Turn of the Year

2 Jan. 2013--A cold sunny day, of the kind C and I have lamented a shortage of in recent JlBlOlX tinEs, at this turn of the year. Apparently the clear weather will linger only today, so we intend to take advantage of it this afternoon with a mild trip to F.dmonds, to walk and do a few stray chores . We similarly treated ourselves nice y'day! New Year's, by ~oinv to the Seattle waterfront arrl in one of our sometime traditions, becoming the first customers of the year for lunch am a beer in Ivar Is bar. (Unlike the old days, the drinks weren ' t free to us firsts . ) With this break in the weather--December had something like 27 rainy days--we 're both feeling pretty good about life. I returned to the Dog Bus this morn, and have done a decent page. Will try for a bit mor e, but that's about the pace this book seems to want . So be it, at least for now . 5 Jan--Saturday, five days of the year gone already. Been a spotty week of writing, what with the first sunny weather drawing us out as mentioned above, but y •day I roughed out a couple of pp . of Donny and the waitress thatfeel pr etty promising. Today I 'd very much like to get going on finances, taxes, etc. , but lack the year-end statements for any of it. At least I can look at re alloting my Vanguard IRA and Roth holdings, with the Barron's and its stock tables that C has just brought from the QFC .