Healthcare Utilization and Cost Trajectories Post-Stroke: Role Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enhancing the Competitiveness of the Health Services Sector in Singapore

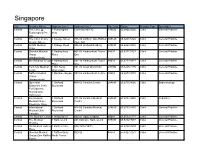

CHAPTER 3 Transforming the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) into a Global Services Hub: Enhancing the Competitiveness of the Health Services Sector in Singapore KAI HONG PHUA Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore NICOLA S POCOCK Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore 1. Introduction Singapore was the first country in the region to officially articulate an aim to attract medical tourists and promote the export of health services overseas. In 2003, the Healthcare Services Working Group (HSWG) of the Economic Review Committee recommended that Singapore attract one million foreign patients by 2012. To achieve this goal, the Singapore Tourism Board (STB), along with the Economic Development Board (EDB) and International Enterprise (IE) Singapore, launched SingaporeMedicine in 2003, a multi-agency initiative that aims to promote, develop and maintain Singapore as an international medical hub. However, in recent years, the push for medical tourism has been muted. Sectiononeof this paper summarizes the Singapore context for a past medical tourism hub policy, followed by an overview of the health system, with policy implications for the system should medical tourism become a major growth area. Methodology is then described in section two, followed by the findings of the SWOT analysis conducted among stakeholders in the health services sector. 111 The objective of this paper is to: 1. Undertake a SWOT analysis for the health services sector in Singapore. 2. Undertake an analysis of policies/regulatory/institutional support for the health services sector in Singapore. 3. Develop a profiling of firms which are considered key players for the health services industry. -

Healthcare List of Medical Institutions Participating in Medishield Life Scheme Last Updated on 1 April 2020 by Central Provident Fund Board

1 Healthcare List of Medical Institutions Participating in MediShield Life Scheme Last updated on 1 April 2020 by Central Provident Fund Board PUBLIC HOSPITALS/MEDICAL CLINICS Alexandra Hospital Admiralty Medical Centre Changi General Hospital Institute of Mental Health Jurong Medical Centre Khoo Teck Puat Hospital KK Women's And Children's Hospital National Cancer Centre National Dental Centre National Heart Centre Singapore National Skin Centre National University Hospital Ng Teng Fong General Hospital Singapore General Hospital Singapore National Eye Centre Sengkang General Health (Hospital) Tan Tock Seng Hospital PRIVATE HOSPITALS/MEDICAL CLINICS Concord International Hospital Farrer Park Hospital Gleneagles Hospital Mt Alvernia Hospital Mt Elizabeth Hospital Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital Parkway East Hospital Raffles Hospital Pte Ltd Thomson Medical Centre DAY SURGERY CENTRES A Clinic For Women A Company For Women A L Lim Clinic For Women Pte Ltd Abraham’s Ear, Nose & Throat Surgery Pte Ltd Access Medical (Bedok South) Access Medical (Bukit Batok) Access Medical (Circuit Road) Access Medical (East Coast) Access Medical (Jurong West) Access Medical (Kim Keat) Access Medical (Marine Terrace) Access Medical (Redhill Close) Access Medical (Tampines 730) Access Medical (Toa Payoh) Access Medical (Whampoa) 2 Access Medical (Teck Ghee) Adult & Child Eye (ACE) Clinic Advance Surgical Group Advanced Centre For Reproductive Medicine Pte. Ltd. Advanced Medicine Imaging Advanced Urology (Parkway East Medical Center) Agape Women’s Specialists -

The Future of Singapore Growing Old with You DBS Asian Insights SECTOR BRIEFING 28 02

SECTOR BRIEFING number DBS Asian Insights DBS Group28 Research • August 2016 The Future of Singapore Growing Old With You DBS Asian Insights SECTOR BRIEFING 28 02 The Future of Singapore Growing Old With You Rachel Tan Equity Analyst DBS Group Research [email protected] Andy Sim, CFA Senior Equity Analyst DBS Group Research [email protected] Produced by: Asian Insights Office • DBS Group Research go.dbs.com/research @dbsinsights [email protected] Chien Yen Goh Editor-in-Chief Jean Chua Managing Editor Geraldine Tan Editor Martin Tacchi Art Director DBS Asian Insights SECTOR BRIEFING 28 03 05 Executive Summary Ageing Population – A Driver of 06 Demand for Healthcare Higher Consumption of Healthcare Who Pays the Medical Bills? 14 Healthcare Infrastructure Singapore’s Medical Infrastructure Versus Peers Growth in Hospital Admissions Driving Increase in Beds and Manpower Plans to Increase Public Medical Services Infrastructure – Healthcare 2020 Masterplan 21 The Healthcare Marketplace Market Segments Within the Healthcare Industry DBS Asian Insights SECTOR BRIEFING 28 04 DBS Asian Insights SECTOR BRIEFING 28 05 Executive Summary Singapore’s society is ageing and the impact is increasingly being felt. In the past decade, Singapore’s residents over 65 years old have grown at a faster rate than the rest of its population. In preparation for this demographic change, the Singapore government published the Population White Paper in 2013, projecting that the number of citizens aged 65 and above will triple to 900,000 by 2030 and the dependency ratio will fall to 2.1 by 2030 from 4.9 in 2015. Healthcare expenditure to triple by 2030. -

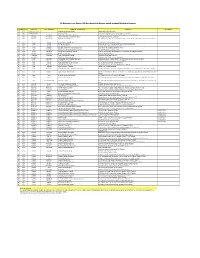

List of Accredited Medical Practitioners

List of Accredited Medical Practitioners As at 18 April 2019 Applicants are advised to contact the doctors to enquire on their professional fees before making an appointment to visit the clinic. SNo Clinic Name Name Address Provided by Doctor Clinic No. Raffles Place, Cecil, Marina, People's Park 1 RafflesMedical Dr Siew Wai Leen 8, Marina View 66360160 #15-01, Asia Square Tower 1 Singapore 018960 2 Fullerton Healthcare (Marina Dr Mythili Pandi 8, Marina Boulevard 63333636 Bay Financial Centre) #01-03/03A, Marina Bay Financial Tower 2 Singapore 018981 3 Fullerton Healthcare (Marina Dr Teo En Qi 8, Marina Boulevard 63333636 Bay Financial Centre) #01-03/03A, Marina Bay Financial Tower 2 Singapore 018981 4 RafflesMedical Dr Prasad Meenakshi 12, Marina Boulevard 66360390 #17-05, Marina Bay Financial Tower 3 Singapore 018982 5 RafflesMedical Dr Steffy 12, Marina Boulevard 66360390 #17-05, Marina Bay Financial Tower 3 Singapore 018982 6 Clinic @ The Sail Dr Lim Chin Wei 2, Marina Boulevard 62255410 #B1-11/12, The Sail @ Marina Bay Singapore 018987 7 Bethesda Medical Clinic Dr Lim Bee Ling Tina 3, Temasek Boulevard 63378933 #B1-124, Suntec City Singapore 038983 8 KN Chin & Associates Pte Dr Chong Kong Hui 3, Temasek Boulevard 63372522 Ltd Medical Practice #02-400, Suntec City Mall Singapore 038983 9 Crawfurd Medical Centre Dr Lin Shengyang 3, Temasek Boulevard 68049580 Nicholas #02-482, Suntec City Mall Singapore 038983 10 G Aesthetic Wellness Dr Xie Ziwei 9, Raffles Boulevard 62660043 Medical Clinic #02-09, Millenia Walk Singapore 039596 11 -

ICN Congress 2019 Singapore Professional Visit on 2 July 2019

ICN Congress 2019 Singapore Professional Visit on 2 July 2019 S/No. Description 1. HEALTH CARE FACILITY: Ang Mo Kio – Thye Hua Kwan Hospital DESCRIPTION OF THE VISIT: Ang Mo Kio – Thye Hua Kwan Hospital is a 360-bed community hospital located in Ang Mo Kio, Singapore. The hospital, which was officially opened in 1993, has been managed by THK, a VWO / Charitable Organisation, since 2002. As a community hospital, care is primarily focused on providing affordable rehabilitative and intermediate care for geriatric patients. MAX. NUMBER OF PARTICIPANTS: 30 PROGRAMME STARTS FROM: 09:00h and ENDS AT: 12:00h BUS DEPARTURE FROM MARINA BAY SANDS AT: 08:00h BUS RETURN TO MARINA BAY SANDS BY :13:00h COST: €50 2. HEALTH CARE FACILITY: Changi General Hospital DESCRIPTION OF THE VISIT: With over 1000 beds serving more than 1 million residents in the East, Changi General Hospital (CGH) offers a wide range of clinical specialties and services, including (but not limited to) the Integrated Sleep Service, Changi Sports Medicine Centre, and a Clinical Trial Research Unit that facilitates biomedical research for better patient care. In 2015, a 280-bed facility, The Integrated Building was opened and is jointly operated with St Andrew's Community Hospital. The first of its kind in Singapore, it was built in support of the new 1 model of care for Geriatric and Rehabilitation services. The building includes mock-up apartments to train patients to resume daily activities so as to get them ready for home. The new Medical Centre completed in 2018, is dedicated to meet complex specialist outpatient needs. -

Direct Settlement Network Report

Singapore City Provider Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Zip Code Phone Provider Type Specialties Central The Clinic @ 1 Fusionopolis Connexis #03-10 138632 65.6466.0602 Clinic General Practice Fusionopolis Pte Way Ltd Central The Clinic at One 1 George Street #05-05 Lobby C One Raffles 049145 65.6438.5322 Clinic General Practice George Street Place Mrt Central ACMS Medical 1 Grange Road #06-06 Orchard Building 239693 65.6262.5052 Clinic General Practice Clinic Central Shenton Medical 1 Harbourfront #01-04 Harbourfront Tower 98633 65.6377.5727 Clinic General Practice Group Place One (Harbourfront) Central Mint Medical Group 1 Harbourfront #01-10 Harbourfront Tower 98633 65.6272.9372 Clinic General Practice Place One Central Twin City Medical 1 Kim Seng #01-32 Great World City 237994 65.6235.1175 Clinic General Practice Centre Promenade Central Raffles Medical 1 Maritime Square #03-56 Harbourfront Centre 99253 65.6273.3078 Clinic General Practice Clinics (Harbourfront) Central Specialist 1 Orchard #04-03 Camden Centre 248649 65.6735.4066 Clinic Endocrinology Endocrine Clinic Boulevard For Diabetes, Thyroid And Hormones Central International 1 Orchard #11-06 Camden Medical 248649 65.6887.4440 Clinic Pediatrics Medical Clinic - Boulevard Centre Paediatric Clinic Central International 1 Orchard #14-06 Camden Medical 248649 65.6733.4440 Clinic General Practice Medical Clinic Boulevard Centre Camden Central The Bonham Clinic 1 Phillip Street #04-02 Lippo Building 48692 65.6533.1177 Clinic General Practice Central The Medical 1 Raffles Link -

Provider List Astra Life for Overseas

RS Rekanan Luar Negeri AAI dan Astra Life khusus untuk product Medicare Premier NO CONTINENT COUNTRY CITY / PROVINCE NAME OF THE HOSPITAL ADDRESS TELEPHONE 1 ASIA Brunei Darussalam Jerudong Park Medical Centre Jerudong Park, BG3122, Brunei 2 ASIA Brunei Darussalam Gleneagles JPMC Jerudong Park Medical Centre , Brunei Darussalam BN2311 3 ASIA Cambodia Siam Reap Royal Angkor International Hospital National Route #6, Phum Kasekam, Khum Sra Ngea, Siem Reap, Cambodia 4 ASIA Cambodia Phnom Penh Sen Sok International University Hospital Street 1986, Phnom Penh, Cambodia 5 ASIA Cambodia Phnom Penh Royal Phnom Penh Hospital Toeuk Thla Village, Russian Federation Blvd.Sangkat Toeuk Thla,Khan Russey Keo, Phnom Pehn, Cambodia 6 ASIA China Beijing Beijing United Family Hospital 2 Jiangtai Rd, Chaoyang, Beijing, China 7 ASIA China Beijing Beijing Eden Hospital E-Building, No.51, Kunming Lake South Road Haidian District,Beijing 8 ASIA China Beijing Tiantan Puhua Hospital 12 Tiantan Nanli, Dongcheng, Beijing, China 9 ASIA China Shanghai Shanghai United Family Hospital and Clinics 1139 Xianxia Rd, Changning, Shanghai, China 10 ASIA China Shanghai Shanghai East International Medical Center 150 Jimo Rd, Pudong, Shanghai, China 11 ASIA China Guangzhou Guangzhou United Family Hospital 1F Annex, PICC Building, 301 Guangzhou Ave, Yuexiu District, Guangzhou 510600 12 ASIA Hong Kong Stubbs Rd HK Adventist Hospital 40 Stubbs Rd, Hong Kong 13 ASIA Hong Kong Tsuen Wan Tsuen Wan Adventist Hospital Hong Kong, Tsuen Raja Circuit 199 14 ASIA Hong Kong Matilda International Hospital 41 Mount Kellett Road, The Peak, Hong Kong 15 ASIA India New Delhi Indraprastha Apollo Hospitals (New Delhi) Indraprastha Apollo Hospitals, Sarita Vihar, Delhi-Mathura Road, New Delhi-110044 16 ASIA India Chennai Apollo Hospitals Chennai 21,Greams Road off.Greams lane, Chennai-600006 17 ASIA India Kolkata Apollo Gleneagles Hospital (Kolkata) No. -

Affordable Excellence: the Singapore Healthcare Story

HASE LTIN This is the story of the Singapore healthcare system: how it works, how it is financed, its history, where it is going, and E what lessons it may hold for national health systems around the world. Singapore ranks sixth in the world in healthcare out- AFFORDABLE comes, yet spends proportionally less on healthcare than any other high-income country. This is the first book to set out a comprehensive system-level description of healthcare in Singapore, with a view to understanding what can be learned from its unique system design and development path. EXC ELLE The lessons from Singapore will be of interest to those currently Affordable planning the future of healthcare in emerging economies, as NC E: THE SINGAPORE HEA E: THE SINGAPORE Excellence well as those engaged in the urgent debates on healthcare in The Singapore Healthcare Story the wealthier countries faced with serious long-term challenges in healthcare financing. Policymakers, legislators, public health by William A. Haseltine officials responsible for healthcare systems planning, finance and operations, as well as those working on healthcare issues in universities and think tanks should understand how the Singa- pore system works to achieve affordable excellence. WILLIAM A. HASELTINE is President and Founder of LT HCARE S ACCESS Health International dedicated to promoting access to high-quality affordable healthcare worldwide, and is President of the William A. Haseltine Foundation for Medical Sciences TORY and the Arts. He was a Professor at Harvard Medical School and was the Founder and CEO of Human Genome Sciences. BROOKINGS Brookings Institution Press Washington, D.C. -

Country Profile: Singapore

Country Profile: Singapore Singapore is a small, stable, highly developed country with an elected parliamentary system of government. Tourist facilities are modern and widely available. Singapore's resident population of over 4.6 million inhabitants (including permanent residents and foreign workers) comprises 75% Chinese, 14% Malay, 9% Indian and 2% others. English is widely spoken. Criminal penalties are strict and law enforcement rigorous; see sections on “Entry/Exit Requirements,” “Special Circumstances,” and “Criminal Penalties,” below, for further details. Read the Department of State Background Notes on Singapore for additional information. COUNTRY OVERVIEW Country Name: Singapore Continent: Asia Capital City: Singapore Boundary Countries: Recommended DIRECT PAYMENT: Alexandra Hospital, Day Surgery Hospitals in International, East Shore Hospital, Gleneagles Hospital Capital: Ltd., Mount Alvernia Hospital, Mount Elizabeth Hospital, National University Hospital, Raffles Hospital, Singapore Day Surgery Center, Singapore General Hospital, Tan Tock Seng Hospital REFERRAL:Changi General Hospital, KK Women’s & Children’s Hospital, National Cancer Center, National Dental Center, National Eye Center, National Heart Center, National Neuroscience Institute, SingHealth Polyclinic – Bedkok, SingHealth Polyclinic – Bukit Merah, SingHealth Polyclinic – Geylang, SingHealth Polyclinic – Marine Parade, SingHealth Polyclinic – Outram, SingHealth Polyclinic – Pasir Ris, SingHealth Polyclinic – Queenstown, SingHealth Polyclinic – Sengkang, SingHealth PolyClinic – Tampines. Main Cities: Singapore Country Size: 692.7 sq km Population: 4,608,167 COUNTRY GENERAL INFORMATION Language: Mandarin 35%, English 23%, Malay 14.1%, Hokkien 11.4%, Cantonese 5.7%, Teochew 4.9%, Tamil 3.2%, other Chinese dialects 1.8%, other 0.9%. Currency: Singapore Dollar (SGD) Predominant Buddhist 42.5%, Muslim 14.9%, Taoist 8.5%, Hindu 4%, Catholic 4.8%, other Christian 9.8%, other 0.7%, Religions: none 14.8%. -

List of Accredited Medical Practitioners

List of Accredited Medical Practitioners As at 1 Sep 2021 Applicants are advised to contact the doctors to enquire on their professional fees before making an appointment to visit the clinic. SNo Clinic Name Name Address Provided by Doctor Clinic No. Raffles Place, Cecil, Marina, People's Park 1 RafflesMedical Dr Siew Wai Leen 8, Marina View 66360160 #15-01, Asia Square Tower 1 Singapore 018960 2 Fullerton Healthcare (Marina Dr Sung Jeng Huang 10, Marina Boulevard 63333636 Bay Financial Centre) John #01-03/03A, Marina Bay Financial Tower 2 Singapore 018981 3 Fullerton Healthcare (Marina Dr Teo En Qi 10, Marina Boulevard 63333636 Bay Financial Centre) #01-03/03A, Marina Bay Financial Tower 2 Singapore 018981 4 RafflesMedical Dr Prasad Meenakshi 12, Marina Boulevard 66360390 #17-05, Marina Bay Financial Tower 3 Singapore 018982 5 RafflesMedical Dr Steffy 12, Marina Boulevard 66360390 #17-05, Marina Bay Financial Tower 3 Singapore 018982 6 Clinic @ The Sail Dr Lim Chin Wei 2, Marina Boulevard 62255410 #B1-11/12, The Sail @ Marina Bay Singapore 018987 7 Bethesda Medical Clinic Dr Lim Bee Ling Tina 3, Temasek Boulevard 63378933 #B1-124, Suntec City Singapore 038983 8 KN Chin & Associates Pte Dr Chong Kong Hui 3, Temasek Boulevard 63372522 Ltd Medical Practice #02-400, Suntec City Mall Singapore 038983 9 Crawfurd Medical Centre Dr Lin Shengyang 3, Temasek Boulevard 68049580 Nicholas #02-482, Suntec City Mall Singapore 038983 10 G Aesthetic Wellness Dr Tan Chung Mui 9, Raffles Boulevard 62660043 Medical Clinic #02-44, Millenia Walk Singapore 039596 11 G Aesthetic Wellness Dr Xie Ziwei 9, Raffles Boulevard 62660043 Medical Clinic #02-09, Millenia Walk Singapore 039596 12 Shenton Medical Group - Dr Edwin Chng Aik Chen 1, Raffles Quay North Tower 63277273 One Raffles Quay #09-02 Singapore 048583 13 Lotus Eldercare Private Dr Tan Jit Seng 1 Raffles Place 68085664 Limited ((Only for referrals from MSF #19-61 Tower 2 or social service organisations Singapore 048616 and persons with disability. -

Healthcare List of Medical Institutions Participating in Medisave Scheme Last Updated on 1 April 2020 by Central Provident Fund Board

1 Healthcare List of Medical Institutions Participating in MediSave Scheme Last updated on 1 April 2020 by Central Provident Fund Board PUBLIC HOSPITALS/MEDICAL CLINICS Alexandra Hospital* Admiralty Medical Centre* Changi General Hospital* Institute of Mental Health Jurong Medical Centre* Khoo Teck Puat Hospital* KK Women's And Children's Hospital* National Cancer Centre National Dental Centre National Heart Centre Singapore National Skin Centre National University Hospital* Ng Teng Fong General Hospital* Singapore General Hospital* Singapore National Eye Centre Sengkang General Hospital* Tan Tock Seng Hospital* PRIVATE HOSPITALS/MEDICAL CLINICS Concord International Hospital Farrer Park Hospital Gleneagles Hospital* Mt Alvernia Hospital* Mt Elizabeth Hospital* Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital Parkway East Hospital* Raffles Hospital Pte Ltd Starmed Specialist Centre Pte Ltd Thomson Medical Centre* PRIVATE CLINIC FOR OUTPATIENT HYPERBARIC OXYGEN THERAPY CLAIM Hyperbaric Medical Services DAY SURGERY CENTRES A Clinic For Women A Company For Women A L Lim Clinic For Women Pte Ltd Abraham’s Ear, Nose & Throat Surgery Pte Ltd Access Medical (Toa Payoh) Access Medical (Bukit Batok) Access Medical (East Coast) Access Medical (Kim Keat) Access Medical (Marine Terrace) Access Medical (Whampoa) Access Medical (Redhill Close) Access Medical (Tampines 730) Access Medical (Circuit Road) Access Medical (Bedok South) *These medical institutions also provide approved Hepatitis B, Pneumococcal and Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccinations to their patients. -

Governing Medical Tourism: the Roles of Singaporean Government

29 Vol. 38, No.1, January - April 2020 Page [29-53] Governing Medical Tourism: The Roles of Singaporean Government Kaewkamol Pitakdumrongkit* Centre for Multilateralism Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore Received 15 July 2019, Received in revised form 24 January 2020, Accepted 25 January 2020, Available online 16 March 2020 Abstract This article seeks to shed light on a question: “What explains a nation’s medical tourism?” This paper focuses on the roles played by a central government in shaping the industry, especially how it balances the advantages and disadvantages of pursuing medical tourism, which has been underexamined. I attempt to fill such intellectual gap by investigating the roles of Singaporean government in affecting the country's medical tourism. Via this case, I demonstrate how the state’s authorities crafted the rules and regulations to promote the sector and simultaneously coped with the adverse effects the industry brings to the nation. Insights from my analysis not only extend the existing literatures on the development of medical tourism and roles of domestic political institutions in shaping states’ policy outcomes, but also provide practitioners with lessons useful for crafting effective policies to sustain their countries’ pursuit of medical tourism. Keywords: Medical Tourism, Healthcare, Political Economy, Political Institutions, Thailand JEL Classifications: I15, I18 * Address: 50 Nanyang Ave, Singapore 639798. Email: [email protected]. Thailand and The World Economy | Vol. 38, No.1, January - April 2020 | 30 1. Introduction Medical tourism, defined as “a phenomenon where a patient travels with or without a companion outside his/her country of residence, to another country for medical treatment” (Medhekar 2010, p.