EW Godwin Furniture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dame Ellen Terry GBE

Dame Ellen Terry GBE Key Features • Born Alice Ellen Terry 27 February 1847, in Market Street, Coventry • Married George Frederic Watts, artist 20 February 1864 in Kensington. Separated 1864. Divorced 13 March 1877 • Eloped with Edward William Godwin, architect in 1868 with whom she had two children – Edith (b1869) and Edward Gordon (b1872). Godwin left Ellen in early 1875. • Married Charles Kelly, actor 21 November 1877 in Kensington. Separated 1881. Marriage ended by Kelly’s death on 17 April 1885. • Married James Carew, actor 22 March 1907 in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, USA. Unofficially separated 1909. • Died 21 July 1928 Smallhythe Place. Funeral service at Smallhythe church. Cremation at Golders Green Crematorium, London. Ashes placed in St Paul’s Covent Garden (the actors’ church). Urn on display on south wall (east end). A brief marital history Ellen Terry married three times and, between husbands one and two, eloped with the man who Ellen Terry’s first marriage was to the artist G F Watts. She was a week shy of 17 years old, young and exuberant, and he was a very neurotic and elderly 46. They were totally mismatched. Within a year he had sent her back to her family but would not divorce her. When she was 21, Ellen Terry eloped with the widower Edward Godwin and, as a consequence, was estranged from her family. Ellen said he was the only man she really loved. They had two illegitimate children, Edith and Edward. The relationship foundered after 6 or 7 years when they were overcome by financial problems resulting from over- expenditure on the house that Godwin had designed and built for them in Harpenden. -

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). -

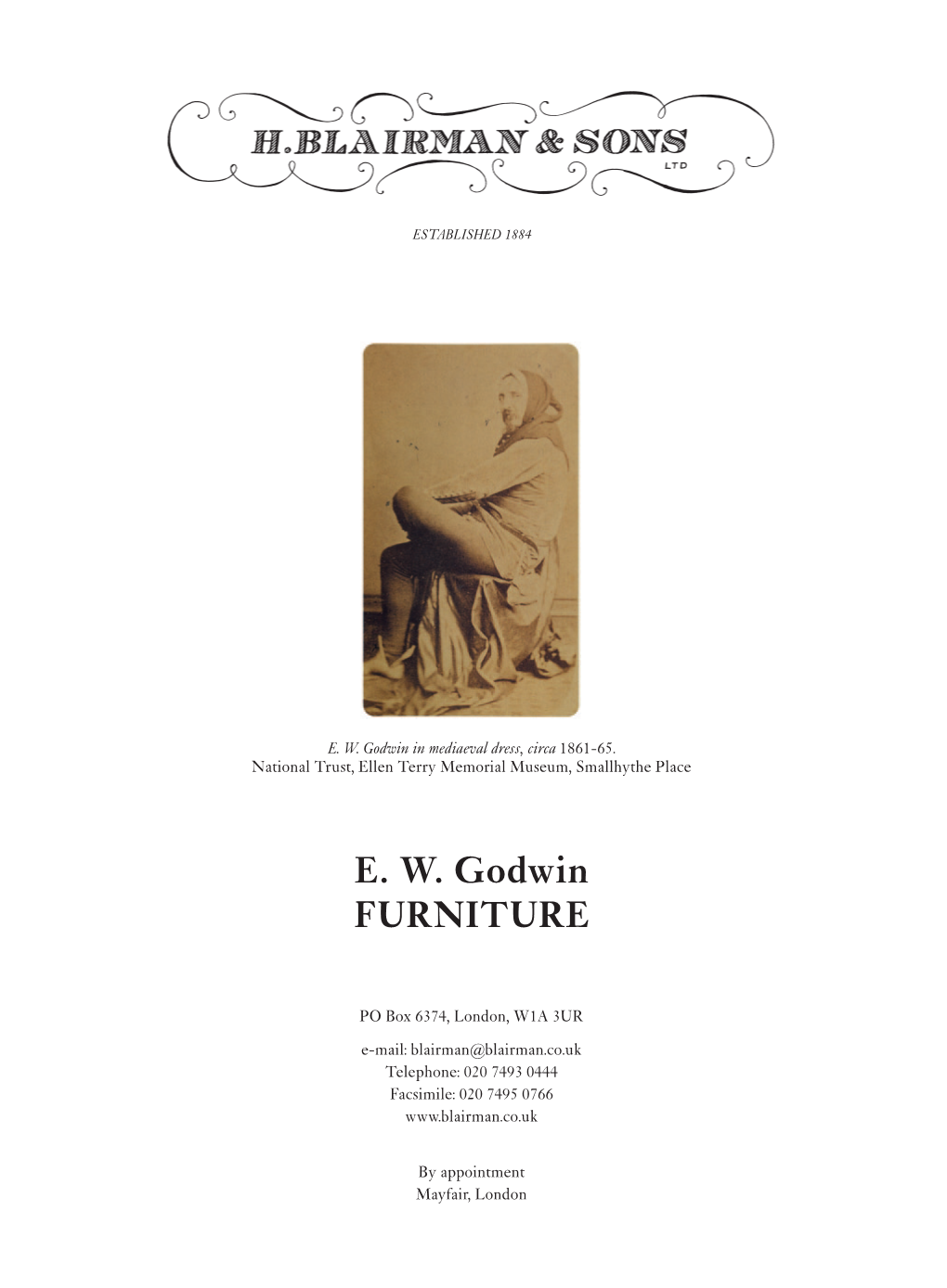

96 When Costume Became Fashion in Victorian Dress: an Exploration Of

96 When costume became fashion in Victorian dress: An exploration of historicity, exoticism and convention in E.W. Godwin’s ‘A Lecture on Dress’ and Lady Clementina Hawarden’s ‘Study from Life’ Kenya Hunt Abstract: Many modern day ideas about women’s dress in fact have their origins in concepts that began in the Victorian era: beauty and utility, historicity and conventionality. As a result, it is important to look at the two poles of adornment and how they framed a battle over woman’s dress that would impact the way future generations viewed the subject. This essay will explore the many ways in which they converged in Victorian design through the examination of two works by two notable Victorian artists: ‘A Lecture on Dress’ by Edward William Godwin and a selected image from Lady Clementina Hawarden’s black and white photographic series, ‘Study from Life’. This essay will also argue that the blurring of the lines between historic costume and contemporary dress led to a permanent transition in personal display and adornment. ______________________________________________________________________________ ‘You look at paintings from whatever century, but you can only date them by the clothes. That means fashion is important’, the couturier Karl Lagerfeld told Women’s Wear Daily recently. 1 His statement is true for perhaps every period of art history but the nineteenth – specifically its latter half, when public dissatisfaction with the fashions of the day gave birth to a revolutionary movement. As the historian Gilles Lipovetsky put it, ‘Fashion as we understand it today emerged during the latter half of the nineteenth century’.2 But it was a general frustration with the contemporary dress of Victorian England that led to a transformation that would allow fashion to become what Lagerfeld calls ‘important’. -

Edward Rycroft MAY 14.Qxp

Furniture Arts and Aesthetics: English Furniture Design of the Late Nineteenth Century By Edward J Rycroft The late nineteenth century saw a shift towards hand craftsmanship in interior design and today it is referred to as the Arts and Crafts Movement. Founded essentially by William Morris, it challenged the machine-made designs and productions of the late Industrial Revolution. Emerging at the same time as the Aesthetic Movement, as well as the Art Nouveau style in France, all of Europe fell under the influence of these three movements and this was to influence the more classical designs which are evident during the Edwardian period. However it can be said that the beginnings of this revolution can be traced to the 1830s with the Gothic Revival style. The Arts and Crafts Fig 4. Late Victorian maho- gany centre table, c1890, movement was based on simple, good design, the use of oak and a return to hexagonal form, serpentine the hand craftsmanship and design honesty of earlier centuries. The Gothic moulded edge on six slender Revival too saw the revival of oak, the use of simple architectural forms Fig.1. 19thC Gothic Revival shaped supports terminating based on medieval buildings and also the use of hand craftsmanship. ecclesiastic arm chair with in a pad foot, circular shelf Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (A.W.N. Pugin) was a major exponent of pierced oak tracery, 60 x 54 x stretcher after the design of the Gothic Revival style. Alongside Charles Barry, he was famous for the 113cm high. Jun 13. Phillip Webb for Morris & designs of the Palace of Westminster, especially the interior, where Pugin Batemans, Stamford. -

Clotilde Brewster Graphic Designer American Expatriate Architect Wendy Midgett Laura Fitzmaurice Printed by Official Offset Corp

NiNeteeNth CeNtury VoluMe 34 NuMber 2 All-British Issue Magazine of the Victorian Society in America All-British Issue n in Honor of tHe 40 tH AnniversAry of tHe vsA L ondon summer scHooL m nineteentH contents century 3 Owen Jones and the Interior Decoration of the voLume 34 • n umber 2 London Crystal Palace Fall 2014 Carol Flores Editor William Ayres 9 “Dear Godwino...” the Wildes and e. W. Godwin Consulting Editor Sally Buchanan Kinsey create an Aesthetic interior Book Review Editor Jennifer Adams Karen Zukowski Advertising Manager / 17 Clotilde Brewster Graphic Designer American expatriate Architect Wendy Midgett Laura Fitzmaurice Printed by Official Offset Corp. Amityville, New York Committee on Publications 27 Tudormania: Chair tudor-period Houses “reconstructed” William Ayres in America and tudor-influenced Warren Ashworth Period rooms in the united states Anne-Taylor Cahill Christopher Forbes Jennifer Carlquist Sally Buchanan Kinsey Michael J. Lewis James F. O’Gorman A History of the VSA London Karen Zukowski 32 Summer School For information on The Victorian Gavin Stamp Society in America, contact the national office: 1636 Sansom Street 34 The Arts and Crafts Movement Philadelphia, PA 19103 in England (215) 636-9872 Alan Crawford Fax (215) 636-9873 [email protected] www.victoriansociety.org 40 Victorian Transfer-printed Ceramics Ian Cox Departments 42 The Bibliophilist 46 Milestones Jeannine Falino He stole the Queen’s Joyce Hill Stoner Knickers Gina Santucci cover: ellen L. clacy (1870-1916), Anne-Taylor Cahill The China Closet, Knole . Watercolor, 1880. victoria & Albert museum, London. the crystal Palace, London, 1851. rakow research Library, corning museum of Glass. -

Nothing Is True but Beauty: Oscar Wilde in the Aesthetic Movement

NOTHING IS TRUE BUT BEAUTY Oscar Wilde in the Aesthetic Movement Jennifer S. Adams Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the History of Decorative Arts Masters Program in the History of Decorative Arts The Smithsonian Associates and the Corcoran College of Art & Design 2009 ©2009 Jennifer S. Adams All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations ii Acknowledgements iii Introduction 1 Chapter One 5 Wilde’s World: Aestheticism and the Victorian Milieu Chapter Two 16 Wilde’s American Lectures: An Aesthetic Cocktail Chapter Three 49 Wilde’s Home: The Aesthetic Architect Meets the Aesthetic Apostle Chapter Four 68 Wilde’s Intentions: Taking Aestheticism into the 1890s Bibliography 76 Illustrations 82 i LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1 Oscar Wilde New York City, 1882 Figure 2 William Holman Hunt (1827–1910) The Awakening Conscience, 1853 Figure 3 Smoking room Halton House, Halton, Buckinghamshire September 1892 Figure 4 Gift of the Magi Morris & Co. tapestry Worcester College Chapel, Oxford University, UK Figure 5 James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) Nocturne in Blue and Silver – Cremorne Gardens, 1872 Figure 6 Congleton Town Hall, Congleton, Cheshire, UK E.W. Godwin, 1866 Figure 7 Frank Miles’s house No. 1 Tite Street, Chelsea, London, UK Figure 8 Oscar Wilde’s house No. 16 Tite Street, Chelsea, London, UK Figure 9 Design for Wilde’s sideboard E.W. Godwin, 1884 Figure 10 Side chair, c. 1880 E.W. Godwin for William Watt Figure 11 Drawing room 54 Melville Street, Edinburgh, Scotland October 1904 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe a debt of gratitude to many individuals and institutions for supporting the conception, research, and writing of this thesis. -

Edward Gordon Craig Notes and Drafts for a Plea to George Bernard Shaw, 1929-1931

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt8b69r9sd No online items Finding Aid for the Edward Gordon Craig Notes and Drafts for a Plea to George Bernard Shaw, 1929-1931 Processed by UCLA Library Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections UCLA Library Special Collections staff Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2008 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. 170/512 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Edward Gordon Craig Notes and Drafts for a Plea to George Bernard Shaw Date (inclusive): 1929-1931 Collection number: 170/512 Creator: Craig, Edward Gordon, 1872-1966 Extent: 3 items, including a proof with holograph notes and two typescript drafts Abstract: The portfolio contains a notebook and two typed manuscripts that trace the development of the essay entitled, "A Plea to G. B. S." in Ellen Terry and her Secret Self (1931; republished as Ellen Terry and her Secret Self, Together with a Plea for G. B. S. in 1932). Edward Gordon Craig's essay "A Plea to G. B. S." is addressed to the British playwright Bernard Shaw, and responds to a preface Shaw had written for his published correspondence with Dame Ellen Terry, a prominent actress and Craig's mother. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. -

Xerox University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This malarial was produoad from a microfilm copy of tha original documant. Whila tha most advanced tachnological means to photograph and reproduce this documant have bean used, tha quality is heavily dependant upon tha quality of tha original submitted. Tha following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Tha sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from tha documant photographad is "Missing Pags(s)". If it was possible to obtain tha missing paga(s) or section, they are spliced into tha film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. Whan an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that tha photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure end thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the pegs in the adjacent frame. 3. Whan a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

A New Road to Modernity1: Thomas Jeckyll‟S Design

Res Mobilis Revista internacional de investigación en mobiliario y objetos decorativos Vol. 5, nº. 5, 2016 A NEW ROAD TO MODERNITY1: THOMAS JECKYLL‟S DESIGN INNOVATIONS OR THE REFORMATION OF THE MID-VICTORIAN DECORATIVE ARTS THROUGH THE JAPANESE CULTURE UN NUEVO CAMINO HACIA LA MODERNIDAD: EL DISEÑO Y LA INNOVACIÓN DE THOMAS JECKYLL O LA REFORMA DE LAS ARTES DECORATIVAS VICTORIANAS A TRAVÉS DE LA CULTURA JAPONESA Johannis Tsoumas* Hellenic Open University Resumen A través de las numerosas turbulencias en el transcurso del diseño y las artes decorativas en Inglaterra en la segunda mitad del siglo diecinueve, destacó la emergencia de un nuevo estilo basado en la filosofía y estética de la cultura japonesa combinada con la tradición británica. El llamado estilo “Anglo-japonés” dentro de un amplio Movimiento Estético, aunque asociado con la decoración más que con la estructura de los objetos, introdujo aspectos innovadores para la abstracción y la geometría en el diseño definiendo de este modo la Modernidad en sí misma. Aunque existieron muchos representantes de este nuevo estilo, Thomas Jeckyll, arquitecto y diseñador menos conocido, a través de su trabajo constituyó la culminación de ese nuevo orden mundial, contribuyendo de una manera silenciosa pero significativa a un nuevo diseño de la realidad estética emergente. Este artículo tiene la intención de investigar a través de los importantes acontecimientos históricos a mitad de época victoriana y las nuevas tecnologías del momento y el efecto de la cultura japonesa impulsada por Jeckyll en la evolución de las artes decorativas británicas hacia la Modernidad. Palabras clave: Modernidad, Estilo Anglo-japonés, Thomas Jeckyll, artes decorativas, metalistería, mobiliario. -

Le Masque De Godwin Sylvain F

Document generated on 09/23/2021 3:05 p.m. L’Annuaire théâtral Revue québécoise d’études théâtrales Le masque de Godwin Sylvain F. Lhermitte Edward Gordon Craig : relectures d’un héritage Article abstract Number 37, printemps 2005 This article attempts to understand the personality and the work of Edward Gordon Craig in the light of his progenitor, Edward William Godwin URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/041592ar (1833-1886). Godwin, whom Craig saw for the last time when he was three, DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/041592ar emerges constantly throughout his work. Deprived of memories, expressing the need for a figure to legitimize his project to revive the Art of the Theater, See table of contents Craig sought to trace the mask of his father: the ghost who appeared to Hamlet; Hamlet with whom Craig so intimately identified. Publisher(s) Centre de recherche en civilisation canadienne-française (CRCCF) et Société québécoise d'études théâtrales (SQET) ISSN 0827-0198 (print) 1923-0893 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Lhermitte, S. F. (2005). Le masque de Godwin. L’Annuaire théâtral, (37), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.7202/041592ar Tous droits réservés © Centre de recherche en civilisation This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit canadienne-française (CRCCF) et Société québécoise d'études théâtrales (SQET), (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be 2005 viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. -

Architectural Japanism in Europe (1860-1910)

The art of Europe challenged by the "other" Architectural Japanism in Europe (1860-1910) Jean-Sébastien CLUZEL ABSTRACT Japanism refers to the whole of Western artistic production—firstly French, and later European and American—inspired by Japanese art and culture. Coming shortly after the gradual reopening of the Japanese archipelago, this artistic movement appeared haltingly in 1854, the date of the forced resumption of dialogue between the shogunate and the United States government, and then fully emerged during the three decades after the official reopening of the country in 1868. European architecture was also affected by this Japanese fashion, whose origins we will present here. Perspective view of the North facade of the Salle des Fêtes, wash drawing published in L’architecture aux salons. Salon de 1897, Armand Guérinet, éditeur des Musées nationaux, Paris, 1897, pl. 175-176. © Bibliothèque Forney. The fall of the Tokugawa government and Emperor Meiji’s recapture of power in 1868 marked the reopening of Japan after two centuries of closure. This political upheaval guided Europe toward the rediscovery of the archipelago. It began in the 1850s through press articles, and quickly followed in the form of universal and industrial exhibitions, in which the Empire of the Rising Sun participated systematically. European enthusiasm for artistic Japan thus began during the 1860s, with the success of “Japanese things” in the World Fairs of 1862 in London, 1867 in Paris, 1873 in Vienna, and once again in Paris. The objects presented during the World Fair of London in 1862 drew the interest of numerous British architects and designers. -

From Victorian to Modernist: the Changing Perceptions of Japanese Architecture Encapsulated in Wells Coates' Japonisme Dovetailing East and West

From Victorian to Modernist: the changing perceptions of Japanese architecture encapsulated in Wells Coates' Japonisme dovetailing East and West Anna Elizabeth Basham Submitted as a partial requirement for the degree of doctor of philosophy, awarded by the University of the Arts London. Research Centre for Transnational Art, Identity and Nation (TrAIN) Chelsea College of Art and Design University of the Arts London April 2007 Volume 1 - thesis IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk VOLUME 1 2 Acknowledgement For making this research possible I should like to thank: my Director of Studies, Dr. Yuko Kikuchi, and my Second Supervisor, Professor Toshio Watanabe, for all their advice, hard work, and in particular, for their enthusiasm for my research; the University of the Arts London (UAL) for enabling me to study on a full-time basis by awarding me a studentship in 2003 and for financing my research at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal in September 2004. I should also like to mention the TrAIN (Research Centre for Transnational, Art, Identity and Nation) and thank members and contributors to the stimulating seminars and lectures, which have expanded my horizons. I should also like to thank the following organisations: The Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal, for allowing me to study the Wells Coates Archive and in particular, Andrea Kuckembuck, Collections Reference Assistant, for her help with the examination of the archive; the Hyman Kreitman Research Centre, Tate Britain for access to the Wells Coates files of the Unit One archive; the University of East Anglia for permitting my study ofthe Wells Coates files within the Pritchard Papers.