Exploring the Theatrical Wardrobe of Ellen Terry a Leading Actress of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dame Ellen Terry GBE

Dame Ellen Terry GBE Key Features • Born Alice Ellen Terry 27 February 1847, in Market Street, Coventry • Married George Frederic Watts, artist 20 February 1864 in Kensington. Separated 1864. Divorced 13 March 1877 • Eloped with Edward William Godwin, architect in 1868 with whom she had two children – Edith (b1869) and Edward Gordon (b1872). Godwin left Ellen in early 1875. • Married Charles Kelly, actor 21 November 1877 in Kensington. Separated 1881. Marriage ended by Kelly’s death on 17 April 1885. • Married James Carew, actor 22 March 1907 in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, USA. Unofficially separated 1909. • Died 21 July 1928 Smallhythe Place. Funeral service at Smallhythe church. Cremation at Golders Green Crematorium, London. Ashes placed in St Paul’s Covent Garden (the actors’ church). Urn on display on south wall (east end). A brief marital history Ellen Terry married three times and, between husbands one and two, eloped with the man who Ellen Terry’s first marriage was to the artist G F Watts. She was a week shy of 17 years old, young and exuberant, and he was a very neurotic and elderly 46. They were totally mismatched. Within a year he had sent her back to her family but would not divorce her. When she was 21, Ellen Terry eloped with the widower Edward Godwin and, as a consequence, was estranged from her family. Ellen said he was the only man she really loved. They had two illegitimate children, Edith and Edward. The relationship foundered after 6 or 7 years when they were overcome by financial problems resulting from over- expenditure on the house that Godwin had designed and built for them in Harpenden. -

A Moor Propre: Charles Albert Fechter's Othello

A MOOR PROPRE: CHARLES ALBERT FECHTER'S OTHELLO A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Scott Phillips, B.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University •· 1992 Thesis Committee: Approved by Alan Woods Joy Reilly Adviser Department of Theatre swift, light-footed, and strange, with his own dark face in a rage,/ Scorning the time-honoured rules Of the actor's conventional schools,/ Tenderly, thoughtfully, earnestly, FECHTER comes on to the stage. (From "The Three Othellos," Fun 9 Nov. 1861: 76.} Copyright by Matthew Scott Phillips ©1992 J • To My Wife Margaret Freehling Phillips ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I express heartfelt appreciation to the members of my thesis committee: to my adviser, Dr. Alan Woods, whose guidance and insight made possible the completion of this thesis, and Dr. Joy Reilly, for whose unflagging encouragement I will be eternally grateful. I would also like to acknowledge the invaluable services of the British Library, the Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee Theatre Research Institute and its curator, Nena Couch. The support and encouragement given me by my family has been outstanding. I thank my father for raising my spirits when I needed it and my mother, whose selflessness has made the fulfillment of so many of my goals possible, for putting up with me. Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Maggie, for her courage, sacrifice and unwavering faith in me. Without her I would not have come this far, and without her I could go no further. -

![Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6681/theater-souvenir-programs-guide-1881-1979-256681.webp)

Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979]

Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979] RBC PN2037 .T54 1881 Choose which boxes you want to see, go to SearchWorks record, and page boxes electronically. BOX 1 1: An Illustrated Record by "The Sphere" of the Gilbert & Sullivan Operas 1939 (1939). Note: Operas: The Mikado; The Goldoliers; Iolanthe; Trial by Jury; The Pirates of Penzance; The Yeomen of the Guard; Patience; Princess Ida; Ruddigore; H.M.S. Pinafore; The Grand Duke; Utopia, Limited; The Sorcerer. 2: Glyndebourne Festival Opera (1960). Note: 26th Anniversary of the Glyndebourne Festival, operas: I Puritani; Falstaff; Der Rosenkavalier; Don Giovanni; La Cenerentola; Die Zauberflöte. 3: Parts I Have Played: Mr. Martin Harvey (1881-1909). Note: 30 Photographs and A Biographical Sketch. 4: Souvenir of The Christian King (Or Alfred of "Engle-Land"), by Wilson Barrett. Note: Photographs by W. & D. Downey. 5: Adelphi Theatre : Adelphi Theatre Souvenir of the 200th Performance of "Tina" (1916). 6: Comedy Theatre : Souvenir of "Sunday" (1904), by Thomas Raceward. 7: Daly's Theatre : The Lady of the Rose: Souvenir of Anniversary Perforamnce Feb. 21, 1923 (1923), by Frederick Lonsdale. Note: Musical theater. 8: Drury Lane Theatre : The Pageant of Drury Lane Theatre (1918), by Louis N. Parker. Note: In celebration of the 21 years of management by Arthur Collins. 9: Duke of York's Theatre : Souvenir of the 200th Performance of "The Admirable Crichton" (1902), by J.M. Barrie. Note: Oil paintings by Chas. A. Buchel, produced under the management of Charles Frohman. 10: Gaiety Theatre : The Orchid (1904), by James T. Tanner. Note: Managing Director, Mr. George Edwardes, musical comedy. -

Broadside Read- a Brief Chronology of Major Events in Trous Failure

NEWSLETTER OF THE THEATRE LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Volume 17, Number 1/Volume 17, Number 2 SPECIAL DOUBLE ISSUE Summer/Fa111989 EXHIBITION SURVEYS MANHATTAN'S EARLY THEATRE HISTORY L An exhibition spotlighting three early New York theatres was on view in the Main I Gallery of The New York Public Library at Lincoln Center from February 13, 1990 through March 31, 1990. Focusing on the Park Theatre on Park Row, Niblo's Garden on Broadway and Prince Street, and Wal- lack's, later called the Star, on Broadway and 13th Street, the exhibition attempted to show, through the use of maps, photo- graphic blowups, programs and posters, the richness of the developing New York theatre scene as it moved northward from lower Manhattan. The Park Theatre has been called "the first important theatre in the United States." It opened on January 29, 1798, across from the Commons (the Commons is now City Hall Park-City Hall was built in 1811). The opening production, As You Like It, was presented with some of the fin- est scenery ever seen. The theatre itself, which could accommodate almost 2,000, was most favorably reviewed. It was one of the most substantial buildings erected in the city to that date- the size of the stage was a source of amazement to both cast and audience. In the early nineteenth century, to increase ticket sales, manager Stephen Price introduced the "star sys- tem" (the importation of famous English stars). This kept attendance high but to some extent discouraged the growth of in- digenous talent. In its later days the Park was home to a fine company, which, in addition to performing the classics, pre- sented the work of the emerging American playwrights. -

ISSUE 3 Autumn 2012

StMartin-MOORINGS_Layout 1 01/11/2012 14:05 Page 1 ISSUE 3 Autumn 2012 Autumn Christmas Set Lunch highlights at The Moorings Hotel n Our homemadeFrom soup of the day theSmoked Tuesdeay haddock fishcake with 4thwhite wine December mand Homemade Christmas Grilled goats cheese with herb veloute pudding with brandy sauce cranberry and walnut salad Escalope of turkey breast with smoked bacon, Vanilla crème brulee Potted crab and prawns served chestnut and sage jus Brown sugar mernigue with granary toast Braised steak in red wine sauce with with whipped cream and Terrine of local game with horseradish mash spiced fruits mulled wine pear chutney Crispy confit of duck with roast root Chocolate and baileys mousse Rillette of salmon wrapped in vegetables and thyme jus with cappuccino cream oak smoked Scottish salmon Roast vegetable and chestnut tart glazed Port creamed stilton with with brie walnut bread Coffee and homemade petit fours 1.75 In this issue: St Martin’s P3 From the Connétable £ are available 2 course 12.50 or 3 course 14.75 Gift Vouchers P4 Steve Luce: never say never for overnight offers and Battle Float Available to Monday to Saturday booking See P5 Parish News: from the Connétable £ £ restaurant reservations, ideal page 11 is advisable Tel: 853633 Christmas presents.... P9 Club News: Jumelage and Battle of Flowers success P22 Farming News: Christmas trees grown in St Martin P24 Sports News: St Martin’s FC looks to the future P29 Church News: over 100 years of service The Moorings Hotel & Restaurant P32 Parish Office www.themooringshotel.com P34 Dates for your Diary The Moorings Hotel and Restaurant Gorey Pier St Martin Jersey JE3 6EW Feature Articles listed on page 3 The answer’s easy.. -

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). -

Noted English Actresses in American Vaudeville, 1904-1916

“The Golden Calf”: Noted English Actresses in American Vaudeville, 1904-1916 Leigh Woods Vaudeville began as a popular American form, with roots in barrooms before audiences of generally Z unsophisticated tastes. By the time it reached its Jessie Millward was known in her native zenith as a popular form during the first two decades country as a heroine in melodramas. Wholesome of this century, however, it showed a pronounced and fresh-faced, she had entered professional acting taste for foreign attractions rather than for the native in 1881, and joined Sir Henry Irving’s prestigious ones that earlier had anchored its broad accessibility. Lyceum company in London as an ingenue the In these years just after the turn of the century, following year. Her first tour of the United States notable foreign actors from the English-speaking came in 1885, and later that year she acted at what theatre made their ways into vaudeville, aligning would become the citadel of London melodrama, the form, though usually in fleeting and superficial at the Adelphi with William Terriss (Millward, ways, with the glamor and prestige the contempor- Myself 315-16). Her name became indissolubly ary stage enjoyed. This pattern bespeaks the linked with Terriss’ as her leading man through willingness to borrow and the permutable profile their appearances in a series of popular melodramas; that have characterized many forms of popular and this link was forged even more firmly when, entertainment. in 1897, Terriss died a real death in her arms Maurice Barrymore (father to Ethel, Lionel and backstage at the Adelphi, following his stabbing John) foreshadowed what would become the wave by a crazed fan in one of the earliest instances of of the future when, in 1897, he became the first violence which can attend modern celebrity (Rowel1 important actor to enter vaudeville. -

A Study of the Management of Charles Kean at The

A STUDY OF THE MANAGEMENT OF CHARLES KEAN AT THE PRINCESS’S THEATRE; l850-l859 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By BUDGE THRELKELD, B. A., M. A. **** The Ohio State University 1955 Approved by Adviser Department of Speech PREFACE When a person approaches a subject with the idea in mind of using that subject for the purpose of a detailed study, he does so with certain provisions. In this instance I was anxious to do a dissertation which would require an extended use of The Ohio State University Theatre Collec tion and which would enable me, at the same time, to do original research. The recent collection, on microfilm, of prompt books of theatrical productions during the nineteenth century provided an opportunity to explore that area in search of a suitable problem. The. possibility of doing research on the management of Charles Kean at the Royal Princesses Theatre was enhanced when tentative probings revealed that the importance of Kean*s management was recog nized by every authority in the field. However, specific and detailed information about the Princesses Theatre and its management was meagre indeed. Further examination of some of the prompt books prepared by Kean for his outstand ing productions at the Princesses convinced me that evidence was available here that would establish Kean as a director in the modern sense of the word. This was an interesting revelation because the principle of the directorial approach to play production is generally accepted to date from the advent of the famous Saxe-Meiningen company. -

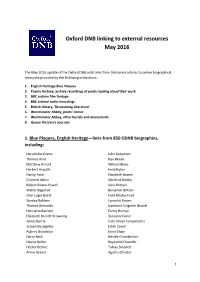

Oxford DNB Linking to External Resources May 2016

Oxford DNB linking to external resources May 2016 The May 2016 update of the Oxford DNB adds links from Dictionary articles to online biographical resources provided by the following institutions: 1. English Heritage Blue Plaques 2. Poetry Archive, archive recordings of poets reading aloud their work 3. BBC archive film footage 4. BBC archive radio recordings 5. British Library, ‘Discovering Literature’ 6. Westminster Abbey, poets’ corner 7. Westminster Abbey, other burials and monuments 8. Queen Victoria’s Journals 1. Blue Plaques, English Heritage—links from 850 ODNB biographies, including: Harold Abrahams John Betjeman Thomas Arne Nye Bevan Matthew Arnold William Blake Herbert Asquith Enid Blyton Nancy Astor Elizabeth Bowen Clement Attlee Winifred Holtby Robert Paden-Powell Vera Brittain Walter Bagehot Benjamin Britten John Logie Baird Ford Madox Ford Stanley Baldwin Lancelot Brown Thomas Barnardo Isambard Kingdom Brunel Henrietta Barnett Fanny Burney Elizabeth Barrett Browning Giovanni Canal James Barrie Cato Street Conspirators Joseph Bazalgette Edith Cavell Aubrey Beardsley Ernst Chain Harry Beck Neville Chamberlain Hilaire Belloc Raymond Chandler Hector Berlioz Tobias Smollett Annie Besant Agatha Christie 1 Winston Churchill Arthur Conan Doyle William Wilberforce John Constable Wells Coates Learie Constantine Wilkie Collins Noel Coward Ivy Compton-Burnett Thomas Daniel Charles Darwin Mohammed Jinnah Francisco de Miranda Amy Johnson Thomas de Quincey Celia Johnson Daniel Defoe Samuel Johnson Frederic Delius James Joyce Charles Dickens -

The Farces of John Maddison Morton

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 The aF rces of John Maddison Morton. Billy Dean Parsons Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Parsons, Billy Dean, "The aF rces of John Maddison Morton." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1940. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1940 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PARSONS, Billy Dean, 1930- THE FARCES OF JOHN MADDISON MORTON. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1971 Speech-Theater University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan © 1971 BILLY DEAN PARSONS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE FAECES OF JOHN MADDISON MORTON A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Speech / by Billy Dean Parsons B.A., Georgetown College, 1955 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1958 January, 1971 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer wishes to express his deep appreciation to Dr•Claude L« Shaver for his guidance and encourage ment in the writing of this dissertation and through years of graduate study• He would also like to express his gratitude to Dr. -

Ellen Tree, Fanny Kemble, and Theatrical Constructions of Gender

"Playing the Men": Ellen Tree, Fanny Kemble, and Theatrical Constructions of Gender Anne Russell, Wilfrid Laurier University Abstract Ellen Tree, the first English performer to regularly play tragic male roles, initiated a nineteenth-century Anglo-American convention in which many women performers played a limited number of tragic male roles, primarily Romeo and Hamlet. Nineteenth-century women's performances of tragic male characters point to multiple tensions and fissures in the understanding and representation of gender in theater. Tree's negotiation of these tensions and her decisions about how, and in what contexts, to play tragic male roles indicate her awareness of the ways in which shifting social perspectives on gender might be accommodated in her stage representations. She followed her enthusiastic and romantic Romeo with Thomas Noon Talfourd's Ion, whose dignified and "classical" character offered a kind of idealized and unsexualized masculinity that was not too deceptively "realistic." Thirty years after she had first performed Romeo with Fanny Kemble as Juliet, Tree attended several of Kemble's public readings of Shakespeare, in which Kemble read all the roles. Tree expressed a combination of admiration and disquiet at the way Kemble "read the men best." Tree's mixed emotions about Kemble's reading register not only her recognition of changing social mores, but also unresolved tensions and ironies in Tree's own theatrical practices. Audience responses to Kemble's readings show astonishment at her intensity and emotionality, particularly her strikingly convincing readings of male characters. These strong audience reactions to Kemble's readings of Shakespeare's plays suggest that the expressions of emotionality possible in public reading could be perceived as more dangerously exciting than stylized and conventional stage performances of the period. -

American Theatrical Tours of Charles Kean

THE AMERICAN THEATRICAL TOURS OF CHARLES KEAN BY RICHARD DENMAN STRAHAN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1984 This study is dedicated to my wife, Rose Earnest Strahan, and to my friend, Andrew M. Jones. Their support and motivation supplied the impetus necessary for its completion. Copyright 1! by Richard Denman Strahan ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Acknowledgement is due the many organizations and individuals without whose assistance this study could not have been done. Many historical societies and libraries graciously supplied materials not otherwise available. Gratitude is expressed to the staff of the Folger Shakespeare Library and to the staff of the Roberts Library at Delta State University, especially Ms. Dorothy McCray whose assistance in securing materials was invaluable. TV TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv ABSTRACT vi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 Notes 5 II. THE THEATRE OF CHARLES KEAN 6 Notes 17 III. THE FIRST TOUR, 1830-33 19 Notes 47 IV. THE SECOND TOUR, 1839-40 51 Notes 65 V. THE THIRD TOUR, 1845-47 67 Notes Ill VI. THE FOURTH TOUR, 1864-66 117 Notes 185 VII. CONCLUSION 196 APPENDIX A. CHRONOLOGY OF PERFORMANCES, FIRST TOUR, 1830-33 .... 203 APPENDIX B. CHRONOLOGY OF PERFORMANCES, SECOND TOUR, 1839-40. ... 214 APPENDIX C. CHRONOLOGY OF PERFORMANCES, THIRD TOUR, 1845-47 .... 221 APPENDIX D. CHRONOLOGY OF PERFORMANCES, FOURTH TOUR, 1864-66. ... 242 BIBLIOGRAPHY 260 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH 266 v Abstract of Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of Florida in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy THE AMERICAN THEATRICAL TOURS OF CHARLES KEAN By Richard Denman Strahan April, 1984 Chairman: Richard L.