Town and Countryside in a Dutch Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TU1206 COST Sub-Urban WG1 Report I

Sub-Urban COST is supported by the EU Framework Programme Horizon 2020 Rotterdam TU1206-WG1-013 TU1206 COST Sub-Urban WG1 Report I. van Campenhout, K de Vette, J. Schokker & M van der Meulen Sub-Urban COST is supported by the EU Framework Programme Horizon 2020 COST TU1206 Sub-Urban Report TU1206-WG1-013 Published March 2016 Authors: I. van Campenhout, K de Vette, J. Schokker & M van der Meulen Editors: Ola M. Sæther and Achim A. Beylich (NGU) Layout: Guri V. Ganerød (NGU) COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) is a pan-European intergovernmental framework. Its mission is to enable break-through scientific and technological developments leading to new concepts and products and thereby contribute to strengthening Europe’s research and innovation capacities. It allows researchers, engineers and scholars to jointly develop their own ideas and take new initiatives across all fields of science and technology, while promoting multi- and interdisciplinary approaches. COST aims at fostering a better integration of less research intensive countries to the knowledge hubs of the European Research Area. The COST Association, an International not-for-profit Association under Belgian Law, integrates all management, governing and administrative functions necessary for the operation of the framework. The COST Association has currently 36 Member Countries. www.cost.eu www.sub-urban.eu www.cost.eu Rotterdam between Cables and Carboniferous City development and its subsurface 04-07-2016 Contents 1. Introduction ...............................................................................................................................5 -

VERSPREIDINGSGEBIED HUIS AAN HUISKRANTEN Regio Noord

Schiermonnikoog Ameland Eemsmond Terschelling De Marne Dongeradeel Loppersum Appingedam Ferwerderadeel Winsum Delfzijl Bedum Kollummerland C.A. Ten Boer Het Bildt Dantumadeel Zuidhorn Leeuwarderadeel Slochteren Groningen Achtkarspelen Grootegast Vlieland Oldambt Menaldumadeel Tytsjerksteradeel Franekeradeel Leek Menterwolde Harlingen Hoogezand-Sappemeer Haren Leeuwaden Marum Littenseradiel Smallingerland Bellingwedde Tynaarlo Veendam Pekela Texel Noordenveld Opsterland Aa en Hunze Assen Stadskanaal Súdwest-Fryslan Vlagtwedde Ooststellingwerf Heerenveen De Friese Meren Den Helder Borger-Odoorn Weststellingwerf Midden-Drenthe Westerveld Hollands Kroon Schagen Steenwijkerland Emmen Coevorden Meppel De Wolden Hoogeveen Medemblik Opmeer Enk- Stede huizen Noordoostpolder Heerhugo- Broec Langedijk waard Urk Bergen Drechterland Hoorn Staphorst Koggenland Zwartewaterland Hardenberg Heiloo Alkmaar Kampen Castricum Beemster Ommen Zeevang Dalfsen Uitgeest Dronten Zwolle Heemskerk Edam Wormerland Purmerend Lelystad Beverwijk Hattem Twenterand Oldebroek Zaanstad Oost- Lands- zaan meer Tubbergen Velsen Waterland Elburg Heerde Raalte Bloemen- Hellendoorn daal Haarlemmer- Dinkelland liede C.A. Olst-Wijhe Almelo Haarlem Amsterdam Almere Nunspeet Wierden Zand- Zeewolde Harderwijk Epe voort Heem- Borne stede Diemen Oldenzaal Muiden Losser Rijssen-Holten Haarlemmermeer Weesp Hille- Ouder- Naarden Huizen Ermelo Hengelo gom Amstel Deventer Amstel- Blari- veen Bussum Noord- Abcoude cum Putten wijker- Lisse Aalsmeer Laren Eemnes Hof van Twente Enschede hout Bunschoten -

TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Formats

STATE OF CALIFORNIA • DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION ADA Notice For individuals with sensory disabilities, this document is available in alternate TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE formats. For alternate format information, contact the Forms Management Unit TR0003 (REV 10/98) at (916) 445-1233, TTY 711, or write to Records and Forms Management, 1120 N Street, MS-89, Sacramento, CA 95814. 1. REPORT NUMBER 2. GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION NUMBER 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NUMBER CA-17-2969 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. REPORT DATE A Comparative Analysis of High Speed Rail Station Development into Destination and/or Multi-use Facilities: The Case of San Jose Diridon February 2017 6. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION CODE 7. AUTHOR 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NO. Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris Ph.D. / Deike Peters, Ph.D. MTI Report 12-75 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS 10. WORK UNIT NUMBER Mineta Transportation Institute College of Business 3762 San José State University 11. CONTRACT OR GRANT NUMBER San José, CA 95192-0219 65A0499 12. SPONSORING AGENCY AND ADDRESS 13. TYPE OF REPORT AND PERIOD COVERED California Department of Transportation Final Report Division of Research, Innovation and Systems Information MS-42, PO Box 942873 14. SPONSORING AGENCY CODE Sacramento, CA 94273-0001 15. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 16. ABSTRACT As a burgeoning literature on high-speed rail development indicates, good station-area planning is a very important prerequisite for the eventual successful operation of a high-speed rail station; it can also trigger opportunities for economic development in the station area and the station-city. At the same time, “on the ground” experiences from international examples of high-speed rail stations can provide valuable lessons for the California high-speed rail system in general, and the San Jose Diridon station in particular. -

Noodverordening COVID-19 Veiligheidsregio Midden- En West-Brabant 25 Augustus 2020)

Noodverordening van de voorzitter van de veiligheidsregio Midden- en West-Brabant houdende voorschriften ter voorkoming van verdere verspreiding van het coronavirus/COVID- 19 (Noodverordening COVID-19 veiligheidsregio Midden- en West-Brabant 25 augustus 2020) De voorzitter van de veiligheidsregio Midden- en West-Brabant, gelet op artikel 176 van de Gemeentewet en artikel 39 van de Wet veiligheidsregio’s; gelet op de aanwijzingen van de minister van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport, mede namens de minister van Justitie en Veiligheid, van 26 juni 2020 nr. 1712697-207530-PG en van 10 juli 2020 nr. 1720717-208077-PG, de aanwijzing van de minister van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport van 30 juni 2020, nr. 1715517-207697-PG, de aanwijzing van de minister van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport van 7 augustus 2020, nr. 1730398-208872-PG en de aanwijzing van de minister van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport van 20 augustus 2020, nr. 1735182-209238-PG; besluit de volgende regeling vast te stellen: Paragraaf 1 Algemene bepalingen Artikel 1.1 Werkingssfeer Deze verordening is van toepassing op het grondgebied van de gemeenten die behoren tot de veiligheidsregio Midden- en West-Brabant, te weten Alphen-Chaam, Altena, Baarle-Nassau, Bergen op Zoom, Breda, Dongen, Drimmelen, Etten-Leur, Geertruidenberg, Gilze en Rijen, Goirle, Halderberge, Hilvarenbeek, Loon op Zand, Moerdijk, Oisterwijk, Oosterhout, Roosendaal, Rucphen, Steenbergen, Tilburg, Waalwijk, Woensdrecht en Zundert. Artikel 1.2 Begripsbepalingen 1. In deze verordening en de daarop berustende -

Met Een Minimum Inkomen Kom Je Soms in Aanmerking Voor Een Steuntje in De Rug

Met een minimum inkomen kom je soms in aanmerking voor een steuntje in de rug: 1. Compensatie eigen risico zorgverzekering Inwoners uit de gemeenten Bedum, De Marne, Winsum en Eemsmond met een inkomen tot en met 120% van het minimum - die in 2018 hun volledig eigen risico hebben verbruikt - hebben recht op compensatie. Aanvragen van compensatie voor het eigen risico zorgverzekering kan via het formulierenloket van Werkplein Ability op www.werkpleinability.nl. De compensatie voor 2018 bedraagt € 265,-. 2. Voedselbank Het Hogeland Voedselbank Het Hogeland biedt tijdelijke ondersteuning aan inwoners uit de gemeenten Bedum, De Marne, Winsum en Eemsmond. Op www.voedselbankhethogeland.nl kun je de voorwaarden vinden waaraan je moet voldoen om in aanmerking te komen voor ondersteuning door de voedselbank. 3. Kinderen van de Voedselbank Kinderen van de Voedselbank verstrekt pakketten met nieuwe kleding, nieuwe schoenen en een aantal leuke nieuwe cadeautjes. Is jouw gezin aangesloten bij de voedselbank, dan kun je een aanvraag indienen voor een pakket voor jouw kind. Het aanvraagformulier is te vinden op www.kinderenvandevoedselbank.nl 4. Kledingbank Maxima Bij Kledingbank Maxima in Winsum kunnen mensen met een minimum inkomen uit de gemeenten Bedum, De Marne, Winsum en Eemsmond tweemaal per jaar gratis winkelen. Kijk voor meer informatie op www.kledingbankmaxima.nl 5. Kraambank Als je een babyuitzet niet zelf kunt betalen, kun je een beroep doen op de Kraambank van Isis Kraamzorg in Groningen. Kijk op www.isiskraamzorg.nl voor meer informatie. 6. Stichting De Vakantiebank Kom je (met of zonder kinderen) rond op of onder bijstandsniveau en ben je meer dan 5 jaar niet op vakantie geweest? Dan kom je in aanmerking voor een mooie vakantie in Nederland. -

Bestekken Van Sarrieshutten Bij De Groninger Korenmolens Gebouwd En Herbouwd in De Periode 1630 - 1805

Tijdens de Open Monumentendag 2013 verscheen het boek: Bestekken van sarrieshutten bij de Groninger korenmolens gebouwd en herbouwd in de periode 1630 - 1805 Het boek is geschreven door B. D. Poppen, uit Uithuizen, kenner op het gebied van de Groninger molens en de sarrieshutten. Eerder schreef hij boeken over De belasting op het gemaal in Stad en Ommelanden 1594-1856 (2004) - nog verkrijgbaar; Aangestelde cherchers of opzichters bij de molens voor de belasting op het gemaal in de provincie Groningen in de periode 1629- 1809 (2013) - beperkte oplage en over de Groninger molenhistorie (2012). Het nu verschenen boek kan worden beschouwd als het derde deel van een trilogie over de intrigerende geschiedenis die zich gedurende enige eeuwen rond de Groninger korenmolens heeft afgespeeld. De sarrieshut bij de verdwenen korenmolen te ’t Zandt. In dit nieuwe boek worden de sarrieshutten, de woningen van de cherchers (controleurs), onder de loep genomen. Zo wordt de bouwgeschiedenis gevolgd van de allereerste bouw in 1630, tot en met de laatste herbouw in 1805. In de tussenliggende jaren zijn talloze reparaties aan de ruim 100 hutten uitgevoerd, die zowel in de stad Groningen als op het platteland waren gebouwd. Middels de vele in het boek opgenomen getranscribeerde bestekken, is op te maken dat de hutten in de loop der jaren niet alleen iets groter werden gebouwd, maar ook van meer comfort werden voorzien. De gedetailleerde bestekken die voor de reparaties en herbouw werden opgesteld, vormen een bijzondere bron van informatie over de toenmalige wijze van bouwen. Het boek omvat 296 pagina’s en is voorzien van ruim 100 afbeeldingen. -

The Port of Rotterdam Paved the Way for the Enormous Extension of Her

P TH E ORT OF ROTTER DA M . was l n i m h n v Like Amsterdam , our city of Rotterdam origina ly oth ng ore t a a illage - wh - In of fishermen and sea faring folk o settled on the banks of the New Maas . the th t w It was th nn n second half of the 1 3 century Ro terdam as incorporated . at e begi i g of 1 6 lh 1 7 th e s t o n the and centuries , that the en rgetic and ys ematic devel pme t of the capacities of the Port of Rotterdam paved the way for the enormous extension of her commerce and navigation . A new was w t w th e New period of prosperity , ho ever , in store for Rot erdam hen rw was w n 25 Wate ay to sea accomplished , enabling ships dra i g feet to reach Rotterdam wi thout breaking bulk . o m u n c of u The p pulation , a o nti g at the ommencement the cent ry to souls , a d 5 t h n w o n in 1 8 0 o as o reached the grand t tal of inhabitants . Th e New t in w D f Maas leaves Rot erdam , trending a esterly direction , passes el s V d n and and o w t N haven , Schiedam , laar i gen Maassluis f rmerly flo ed in o the orth Sea w without the aid of any artificial works . This natural high ay from Rotterdam to tw u n a a o sea was followed by ships of the largest tonnage o h dred ye rs g . -

Food for the Future

Food for the Future Rotterdam, September 2018 Innovative capacity of the Rotterdam Food Cluster Activities and innovation in the past, the present and the Next Economy Authors Dr N.P. van der Weerdt Prof. dr. F.G. van Oort J. van Haaren Dr E. Braun Dr W. Hulsink Dr E.F.M. Wubben Prof. O. van Kooten Table of contents 3 Foreword 6 Introduction 9 The unique starting position of the Rotterdam Food Cluster 10 A study of innovative capacity 10 Resilience and the importance of the connection to Rotterdam 12 Part 1 Dynamics in the Rotterdam Food Cluster 17 1 The Rotterdam Food Cluster as the regional entrepreneurial ecosystem 18 1.1 The importance of the agribusiness sector to the Netherlands 18 1.2 Innovation in agribusiness and the regional ecosystem 20 1.3 The agribusiness sector in Rotterdam and the surrounding area: the Rotterdam Food Cluster 21 2 Business dynamics in the Rotterdam Food Cluster 22 2.1 Food production 24 2.2 Food processing 26 2.3 Food retailing 27 2.4 A regional comparison 28 3 Conclusions 35 3.1 Follow-up questions 37 Part 2 Food Cluster icons 41 4 The Westland as a dynamic and resilient horticulture cluster: an evolutionary study of the Glass City (Glazen Stad) 42 4.1 Westland’s spatial and geological development 44 4.2 Activities in Westland 53 4.3 Funding for enterprise 75 4.4 Looking back to look ahead 88 5 From Schiedam Jeneverstad to Schiedam Gin City: historic developments in the market, products and business population 93 5.1 The production of (Dutch) jenever 94 5.2 The origin and development of the Dutch jenever -

Sybold Van Ravesteyn

Sybold van Ravesteyn. Sybold van Ravesteyn, geboren als Sijbold van Ravesteijn (Rotterdam, 18 februari 1889 - Laren (Noord-Holland), 23 november 1983) was een Nederlands architect. Leven en werk Sybold van Ravesteyn had een grote kennis van gewapend beton. In het begin leek hij een aanhanger van het Nieuwe Bouwen, maar al vroeg experimenteerde hij met barokke krullen en andere ronde vormen. In 1921 werd hij architect voor de Nederlandse Spoorwegen. Zijn eerste eigen ontwerp waren een goederenloods en kantoren in Arnhem (1924). In Utrecht ontwierp Van Ravesteyn rond 1932 aan de Prins Hendriklaan (112) voor zichzelf en zijn gezin een woonhuis dat nog gebaseerd was op het Nieuwe Bouwen. Na een reis naar Rome begon hij van het modernisme af te wijken door ornamenten en decoraties in zijn ontwerpen te gaan gebruiken. In 1938 ontwierp hij een neobarokke uitbreiding voor schouwburg Kunstmin in Dordrecht. Ook gebouw De Holland aan de Burgemeester de Raadtsingel in Stichting Cultureel erfgoed Enschede. [2016] Pagina 1 Sybold van Ravesteyn. Dordrecht werd door hem getekend. Een ander beroemd ontwerp van Van Ravesteyn is Diergaarde Blijdorp in Rotterdam(bouwjaar 1939-1941). Van Ravesteyn is daarmee een van de weinige architecten ter wereld die een gehele dierentuin naar eigen inzicht heeft mogen ontwerpen. Van Ravesteyn heeft door heel Nederland voor de Nederlandse Spoorwegen stations en seinhuizen ontworpen. Een groot aantal hiervan, waaronder het Station Rotterdam Centraal (1957) en de stationsgebouwen van -Blaak, - Hofplein en -Zuid, Utrecht Centraal en 's-Hertogenbosch, zijn inmiddels weer gesloopt. Dicht bij het station van Maastricht staat nog altijd een recent gerestaureerd seinhuisje van Van Ravesteyn. -

Waterkwaliteitsopgave 2016-2021 Uitwerking Voor De Waterlichamen

Waterkwaliteitsopgave 2016-2021 Uitwerking voor de waterlichamen Factsheets, september 2015 1 Inhoudsopgave Stroomgebieden Waterschap Rijn en IJssel ................................................................................................. 2 Stroomgebied Schipbeek ............................................................................................................................. 3 Buurserbeek ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Dortherbeek ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Dortherbeek-Oost......................................................................................................................................... 9 Elsbeek (Nieuwe waterleiding) ................................................................................................................... 12 Oude Schipbeek .......................................................................................................................................... 14 Schipbeek.................................................................................................................................................... 16 Zoddebeek .................................................................................................................................................. 19 Zuidelijk afwateringskanaal ....................................................................................................................... -

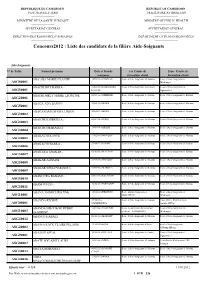

Concours2012 : Liste Des Candidats De La Filière Aide-Soignants

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON PAIX-TRAVAIL-PATRIE PEACE-WORK-FATHERLAND ----------------------- ----------------------- MINISTERE DE LA SANTE PUBLIQUE MINISTRY OF PUBLIC HEALTH ----------------------- ----------------------- SECRETARIAT GENERAL SECRETARIAT GENERAL ----------------------- ----------------------- DIRECTION DES RESSOURCES HUMAINES DEPARTMENT OF HUMAN RESOURCES ----------------------- ----------------------- Concours2012 : Liste des candidats de la filière Aide-Soignants Aide-Soignants: N° de Table Nomset prénoms Date et lieu de 1er Centre de 2ème Centre de naissance formation choisi formation choisi ABA ABA MARIE CLAUDE 12/09/84 à ENONGAL Ecole d'Aide-Soignants d'Ebolowa Ecole d'Aide-Soignants de ASG80001 Mbalmayo ABACHONLE BARKA - 24/06/93 à KORO KORO Ecole d'Aide-Soignants de Garoua Ecole d'Aide-Soignants de ASG30001 KALFOU Ngaoundéré ABADIE MELY MARIE LEONTINE 08/03/88 à NDELELE Ecole d'Aide-Soignants de Garoua Ecole d'Aide-Soignants de Batouri ASG20001 ABAGA ADA BANYO 29/06/92 à MORA Ecole d'Aide-Soignants de Garoua Ecole d'Aide-Soignants de Maroua ASG50001 ABAGANAMA MAMA LIMAN 20/05/87 à MORA Ecole d'Aide-Soignants de Maroua Ecole d'Aide-Soignants de Garoua ASG30002 ABAÏCHO DJIBRILLA - 01/02/94 à BODO Ecole d'Aide-Soignants de Maroua Ecole d'Aide-Soignants de Garoua ASG30003 ABAICHO MAHAMAT - 13/09/90 à AFADE Ecole d'Aide-Soignants de Maroua Ecole d'Aide-Soignants de Garoua ASG30004 ABAKACHI KANTE 14/02/88 à WOULKY Ecole d'Aide-Soignants de Maroua Ecole d'Aide-Soignants de Garoua ASG30005 ABAKACHI BARKA -

International Social Security Review

4.3 VOLUME | NUMBER 72 2 | APRIL– JUNE |2019 VOLUME 72 | NUMBER 2 www.issa.int APRIL–JUNE 2019 The International Social Security Association (ISSA) is the world’s leading international organization bringing together national social security administrations and agencies. The ISSA provides information, research, expert advice and platforms for members to build and promote dynamic social security systems and policy worldwide. International 2 | 2019 Social Security Review International Social Security Review Social International Second-pillar pensions in Central and Eastern Europe: Payment constraints and exit options Effective retirement age from employment and full-time employment, and the impact of the 2008 crisis How fair are unemployment benefits? The experience of East Asia Employer-oriented labour market policies in Sweden: Creating jobs and the division of labour in the public sector Social health protection in Cambodia: Challenges of policy design and implementation View this journal online at wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/issr INTERNATIONAL SOCIAL SECURITY ASSOCIATION ASSOCIATION INTERNATIONALE DE LA SÉCURITÉ SOCIALE ASOCIACIÓN INTERNACIONAL DE LA SEGURIDAD SOCIAL INTERNATIONALE VEREINIGUNG FÜR SOZIALE SICHERHEIT Editorial Board First published in 1948, the International Social Security Review is the world’s major international quarterly pub- Chairperson Julien Damon, Sciences Po, Paris, Ecole nationale supérieure de sécurité sociale, France lication in the field of social security. Articles by leading academics and social security experts around the world Vice Chairperson Wouter van Ginneken, Independent Consultant, Geneva, Switzerland present international comparisons and in-depth discussions of topical questions as well as studies of social security Members Willem Adema, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris, France systems in different countries, and there are regular reviews of the latest publications in its field.