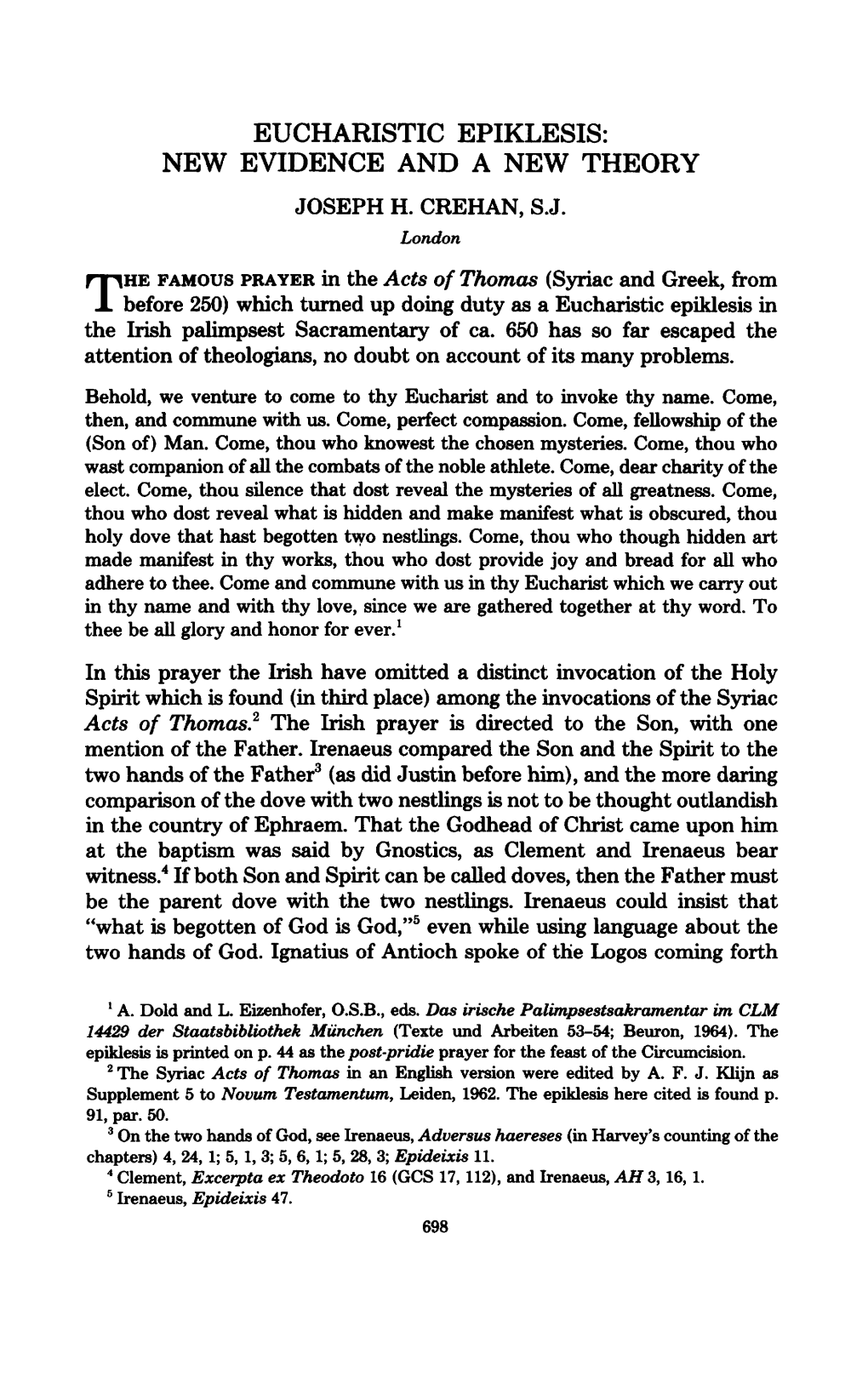

Eucharistic Epiklesis: New Evidence and a New Theory Joseph H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tradition of the Female Deacon in the Eastern Churches

The Tradition of the Female Deacon in the Eastern Churches Valerie Karras, Th.D., Ph.D. and Caren Stayer, Ph.D. St. Phoebe Center Conference on “Women and Diaconal Ministry in the Orthodox Church: Past, Present, and Future” Union Theological Seminary, New York, NY December 6, 2014 PURPOSE OF HISTORY SESSION • To briefly review the scholarship on the history of the deaconess, both East and West • To lay the groundwork for discussions later in the day about the present and future • To familiarize everyone with material you can take with you • Book list; book sales • We ask you to share and discuss this historical material with others in your parish TIMELINE—REJUVENATION FROM PATRISTIC PERIOD (4TH -7TH C.) • Apostolic period (AD 60-80): Letters of Paul (Rom 16:1 re Phoebe) • Subapostolic period (late 1st/early 2nd c.): deutero-Pauline epistles (I Tim. 3), letter of Trajan to Pliny the Younger • Byzantine period (330-1453) − comparable to Early, High, and Late Middle Ages plus early Renaissance in Western Europe • Early church manuals (Didascalia Apostolorum, late 3rd/early 4th c.; Testamentum Domini, c.350; Apostolic Constitutions, c.370, Syriac) • 325-787: Seven Ecumenical Councils • Saints’ lives, church calendars, typika (monastic rules), homilies, grave inscriptions, letters • 988: conversion of Vladimir and the Rus’ • 12th c. or earlier: office of deaconess in Byz. church fell into disuse • Early modern period in America • 1768: first group of Greek Orthodox arrives in what is now Florida • 1794: first formal Russian Orthodox mission arrives in what is now Alaska BYZANTINE EMPIRE AND FIVE PATRIARCHATES CIRCA 565 A.D. -

Canon Law of Eastern Churches

KB- KBZ Religious Legal Systems KBR-KBX Law of Christian Denominations KBR History of Canon Law KBS Canon Law of Eastern Churches Class here works on Eastern canon law in general, and further, on the law governing the Orthodox Eastern Church, the East Syrian Churches, and the pre- Chalcedonean Churches For canon law of Eastern Rite Churches in Communion with the Holy See of Rome, see KBT Bibliography Including international and national bibliography 3 General bibliography 7 Personal bibliography. Writers on canon law. Canonists (Collective or individual) Periodicals, see KB46-67 (Christian legal periodicals) For periodicals (Collective and general), see BX100 For periodicals of a particular church, see that church in BX, e.g. BX120, Armenian Church For periodicals of the local government of a church, see that church in KBS Annuals. Yearbooks, see BX100 Official gazettes, see the particular church in KBS Official acts. Documents For acts and documents of a particular church, see that church in KBS, e.g. KBS465, Russian Orthodox Church Collections. Compilations. Selections For sources before 1054 (Great Schism), see KBR195+ For sources from ca.1054 on, see KBS270-300 For canonical collections of early councils and synods, both ecumenical/general and provincial, see KBR205+ For document collections of episcopal councils/synods and diocesan councils and synods (Collected and individual), see the church in KBS 30.5 Indexes. Registers. Digests 31 General and comprehensive) Including councils and synods 42 Decisions of ecclesiastical tribunals and courts (Collective) Including related materials For decisions of ecclesiastical tribunals and courts of a particular church, see that church in KBS Encyclopedias. -

Twenty-Five Consecration Prayers, with Notes and Introduction

TR AN SLAT ION S OF CHRIST IAN LITE RATUR E SE R I ES I I I L I T U R G I C A L T E ! T S E D D BY FELT E D TE C . O D . I : L‘ , TWEN TY- F I V E C O N SEC RAT IO N P RA YE R S P R EFA C E A WI DE SP RE AD interes t in th e gre at liturgies h as b een arouse d by th e publication o f th e Anglican E uchari s tic P rayer as re vised by th e Co nvocatio n o f Cant e rbury ; and this boo k attempts to prese nt to th ose wh o are e es e e e u c m e s th e int r t d , but unl arn d , in lit rgi al att r , e E c s P e s of th e C e gr at u hari tic ray r hurch , giv n in full , th e e cess o s e o th e s but with Int r i n indicat d nly , rubric om e th e es o ses o f De o e o e itt d , and r p n ac n and p pl i se e e s s o as t o m e mo e e s th e n rt d in brack t , ak r a y com o o n e paris n f e ach with th e A glican P ray r . -

Baptism – the What, Who and How – Beginning with John the Baptizer

Baptism – the What, Who and How – Beginning with John the Baptizer Introduction In this study I have relied heavily on the research that has been done by: 1. A. Andrew Das, “Baptized Into God's Family” Milwaukee(NWPH -Impact Series) 1991 2. Dwight Hervey Small, “The Biblical Basis for Infant Baptism” (Baker/Grand Rapids)1968 3. Two of the major resources which Das relies on are: Joachim Jeremias, “Infant Baptism in the First Four Centuries” Transl. David Cairns(Westminster Press/Philadelphia) 1962, Oscar Cullman, “Baptism in the New Testament” J. K. Reid(transl.)(Westminster/Philadelphia) 1950. John the baptizer was to go before our Lord as an Elijah to announce the Messiah's arrival. He was also a transitional person. With John there is the transition to New Testament baptism which then our Lord gave as the risen Savior for His church to carry out. Baptism was not new, as the Jews already practiced it with their converts coming into the church. With John we have a transition from what was already known to the Jews about a baptism to then Jesus' Great Commission. At some point in Jesus' ministry His disciples began to baptize and as time passed they were baptizing more disciples than John. Jn. 4:1 This is also an indication of a transition. John stated that his task was to recede out of the picture as Jesus increased. When John is told “all are going to Him” (Jn. 3:26) it does not bother John at all. The “making and baptizing...disciples” of Jesus' disciples was a continuance of what John had been doing. -

“In the Syrian Taste”: Crusader Churches in the Latin East As Architectural Expressions of Orthodoxy “Ao Sabor Sírio”

BLASCO VALLÈS, Almudena, e COSTA, Ricardo da (coord.). Mirabilia 10 A Idade Média e as Cruzadas La Edad Media y las Cruzadas – The Middle Ages and the Crusades Jan-Jun 2010/ISSN 1676-5818 “In the Syrian Taste”: Crusader churches in the Latin East as architectural expressions of orthodoxy “Ao sabor sírio”: as igrejas dos cruzados no Oriente latino como expressões da arquitetura ortodoxa Susan BALDERSTONE 1 Abstract : This paper explores how the architectural expression of orthodoxy in the Eastern churches was transferred to Europe before the Crusades and then reinforced through the Crusaders’ adoption of the triple-apsed east end “in the Syrian Taste” 2 in the Holy Land. Previously, I have shown how it can be deduced from the archaeological remains of churches from the 4th-6th C that early church architecture was influenced by the theological ideas of the period 3. It is proposed that the Eastern orthodox approach to church architecture as adopted by the Crusaders paralleled the evolution of medieval theology in Europe and can be seen as its legitimate expression. Resumo : Este artigo explora o modo como a expressão arquitetônica da ortodoxia nas igrejas orientais foi transferida para a Europa antes das Cruzadas e, em seguida, reforçada através da adoção dos cruzados da abside tripla “de gosto sírio” na Terra Santa. Anteriormente, eu mostrei como isto pôde ser deduzido dos restos arqueológicos de igrejas dos séculos IV-VI e como a arquitetura da igreja primitiva foi influenciada pelas idéias teológicas do período. Proponho que a abordagem do Oriente ortodoxo para a arquitetura da igreja foi adotada pelos cruzados paralelamente à evolução da teologia medieval na Europa, e pode ser visto como uma expressão legítima. -

A Study of the Antecedents of in Persona Christi Theology in Ancient Christian Tradition

The Representation of Christ by the Priest: A Study of the Antecedents of in persona Christi Theology in Ancient Christian Tradition G. Pierre Ingram, CC Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Theology, Saint Paul University, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Theology Ottawa, Canada April 2012 © G. Pierre Ingram, Ottawa, Canada, 2012 To my parents: Donald George Ingram († 1978) and Pierrette Jeanne Ingram († 2005) Contents Abbreviations ...................................... .......................... vi INTRODUCTION ....................................... .............................1 1 Contemporary Context ............................. ............................1 2 Statement of the Problem ......................... ..............................2 3 Objectives....................................... ............................5 4 Research Hypothesis .............................. ............................5 5 Methodological Approach .......................... ............................6 6 Structure of the Dissertation . .................................7 CHAPTER 1 THE USE OF "IN PERSONA CHRISTI" IN CATHOLIC TEACHING AND THEOLOGY . 9 1 Representation of Christ as a Feature of the Theology of Ministry in General . 9 2 The Use of the Phrase in persona Christi in Roman Catholic Theology . 11 2.1 Pius XI ........................................ ....................13 2.2 Pius XII ....................................... ....................14 2.3 The Second Vatican Council ..................... ......................21 -

Jesus, Women, and the New Testament by Tarcisio Beal

Jesus, Women, and the New Testament by Tarcisio Beal EDITOR’S NOTE: This article is a follow up to the article, his body with spices. No surprise, then that, after his resurrec- Androcentrism Weakens Church and Society, that appeared in the tion, He appeared frst to a woman, namely, Mary of Magdala September, 2020 issue of La Voz de Esperanza. (Mk 15: 40-41; 16: 1-2; Rev 21: 43). Jesus never excluded any woman from his love and message. He even lovingly mentions If there’s anything that contradicts the praxis of Jesus and the a non-Jewish, foreign woman, namely, the Sidonian widow of teachings of the New Testament, it is the machismo that has per- Zarephath, who was fed by the prophet Elijah during a great vaded institutional Christianity and world society for more than famine (Lk 4: 25-27). 19 centuries. What Christianity and society have lost by practic- Furthermore the Acts of the Apostles contain a number of ing androcentrism (from Greek andrós: man, male) and misogy- passages which attest that women were an integral part of the nism (gyné: woman, female) is beyond any calculation. Even early Christian communities: Mary, several women, and male more tragic is the fact that most religions, including the many apostles pray in Jerusalem in the upper room of the house Christian and most Muslim denominations have been and con- where they were staying (Acts 1: 14); the election of Mathias tinue to follow such ungodly behavior—barring women from the to replace Judas Iscariot was carried out by a congregation of altar, from the priesthood 120 persons that included and from any signifcant women (Acts 8: 15-26); institutional authority. -

Die Kirchenordnung Aus Dem Testamentum Domini Nostri Jesu Christi Nach Den Redaktionen Der Handschriften Borg

Die Kirchenordnung aus dem Testamentum Domini Nostri Jesu Christi nach den Redaktionen der Handschriften Borg. arab. 22 und Petersburg or. 3 D i s s e r t a t i o n zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Philosophie in der Philosophischen Fakultät der Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen vorgelegt von Andreas Johannes Ellwardt aus Kehl 2018 Gedruckt mit Genehmigung der Philosophischen Fakultät der Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen Dekan: Prof. Dr. Jürgen Leonhardt Hauptberichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Stephen Gerö Mitberichterstatter: PD Dr. Dmitrij Bumazhnov Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 25. Juli 2013 Universitätsbibliothek Tübingen: TOBIAS-lib INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Abgekürzt zitierte Literatur 2 Einführung: Kirchenordnungen 3 Die ältesten pseudapostolischen Kirchenordnungen I: Didache und Didaskalie 5 Exkurs: zur pseudepigraphen apostolischen Verfasserschaft 6 Die ältesten pseudapostolischen Kirchenordnungen II: Traditio Apostolica 9 Zur überlieferungsgeschichtlichen Einordnung: Alexandrinischer Sinodos und 11 pseudoklementinischer Oktateuch Rekonstruktion der Traditio Apostolica 12 Testamentum Domini Nostri Jesu Christi 18 Die arabischen Redaktionen des Testamentum Domini 23 Inhalt und Aufbau des Testamentum Domini 28 Zur vorliegenden Edition 34 Text des Kirchenordnungsteils aus dem Testamentum Domini 39 Übersetzung des Kirchenordnungsteils aus dem Testamentum Domini 90 Abschließende Überlegungen 175 Verwendete Literatur 177 Anhang: Reproduktionen der Handschriften Borg. arab. 22 und Petersburg or. 3 185 1 ABGEKÜRZT ZITIERTE LITERATUR Rahmani: IGNATIUS EPHRAEM II. RAHMANI (Hg.), Testamentum Domini Nostri Jesu Christi. Nunc primum edidit, latine reddidit et illustravit, Mainz 1899. Cooper/ Maclean: JAMES COOPER; ARTHUR J. MACLEAN, Testament of Our Lord Translated into English from Syriac. with introduction and notes, Edinburgh 1902. Nau: FRANÇOIS NAU, La version syriaque de l’octateuque de Clément, Paris 1913 (= Ancienne littérature canonique syriaque 4). -

From Jerusalem to Rome

FROM JERUSALEM TO ROME The Jewish origins and Catholic tradition of liturgy Michael Moreton 2018 Copyright © 2018, Estate of Michael Moreton All rights reserved. This work may be freely redistributed, but not modified in any way except by the copyright holders I continue unto this day, witnessing both to small and great, saying none other things than those which the prophets and Moses did say should come: That Christ should suffer, and that he should be the first that should rise from the dead, and that he should show light unto the people, and to the Gentiles. Acts 26:22,23 And the night following, the Lord stood by him, and said, Be of good cheer, Paul: for as thou hast testified concerning me in Jerusalem, so must thou bear witness also at Rome. Acts 23:11 Contents Preface ix Acknowledgements xiii Editorial note xv Abbreviations xvi 1 Israel and the Church 1 2 Synagogue and Church 7 3 The Daily Prayer of Israel and the Church 15 (i) The Tefillah: the sanctification of time 15 (ii) The Lord's Prayer 27 (iii) Prayer in the catechumenate in the second century 30 (iv) Daily prayer in the third century 31 (v) Daily prayer in the basilica 35 (vi) Monastic prayer 37 (vii) The dis-integration of the Church's prayer 40 (viii) Reform 42 4 The Faith of the Church 47 (i) The Christ event and Christology 47 (ii) The content of the faith and baptism 49 (iii) Catechesis, the contract, and the baptismal formula in the East 53 Synopsis: The Creed in the East 58 (iv) Catechesis, the contract, and the baptismal formula in Apostolic Tradition and related -

Survey of Regent Biblical Literature

147 SURVEY OF REGENT BIBLICAL LITERATURE. lNTRODUCTION.-In connection with the text of the New Testa ment much good work has been done in our time, but probably that which will be most conspicuously monumental is the edition of the V ulgate by Bishop W ordsworth and Vice-Principal White. The editors have the satisfaction of knowing that their work need never be done over again, and that theirs will be the critical edition for all time. With such reward, scholars such as they are compensated even for the enormous labour spent upon this edition. Great credit is due also to the Clarendon Press for the perfect form in which it is issued. The part now issued [Partis Prioris Fasciculus Tertius] contains the Gospel according to St. Luke. The title of the whole is Novum Testamentum Domini Nostri Jesu Ohristi Latine secundum editionem Sancti Hieronymi. A not ignoble rivalry between the Oxford and Cambridge University Presses is productive of great advantage to the public. The Oxford Bible for Teachers, which in previous editions has be come so deservedly popular is now issued in a form which should secure for it a still wider acceptance with all English-reading peoples. The Helps to the Study of the Bible are issued in a separate form, but even when bound up with the beautifully printed Bible, they do not swell the volume to an inconvenient size, indeed scarcely to an appreciable extent. But the size does not measure the importance of these Helps. In this edition what ever accuracy and whatever completeness are possible have been attained. -

The Oliver Beckerlegge Bible Collection

The Oliver Beckerlegge Bible Collection 1. [Church of England. Beckerlegge]. A bound volume containing: a. The booke of common prayer: with the psalter or Psalmes of David, of that translation which is appointed to be vsed in churches. Imprinted at London: By Robert Barker, printer to the Kings most Excellent Maiestie, Anno 1613. ESTC, S123078. b. [The booke of common prayer and administration of the sacraments, and other rites and ceremonies of the Church of England. Imprinted at London: By Robert Barker, printer to the Kings most excellent Maiestie, Anno 1615.] ESTC, S108689. c. Bible. O.T. Psalms. English. Sternhold and Hopkins. The whole book of Psalmes: collected into English meeter by Thomas Sternhold, Iohn Hopkins, and others, conferred with the Hebrew, with apt notes to sing them withall. Set forth and allowed to be sung in all churches, of all the people together, before and after morning and euening prayer: and also before and after sermons, & moreouer in priuate houses for their godly solace and comfort, laying apart all vngodly songs and ballades, which tend onely to the nourishing of vice, and corrupting of youth. London: Printed [by Richard Field] for the Companie of Stationers, 1616. ESTC, S121126. d. Speed, John. The genealogies recorded in the Sacred Scriptures, according to euery family and tribe: With the line of Our Sauiour Iesvs Christ, obserued from Adam to the Blessed Virgin Mary / by I.S. [London: printed by John Beale, 1611 or 1612] ESTC, S101955. e. Bible. English. Authorised. The Holy Bible, containing the Old Testament, and the New: newly translated out of the original tongues : and with the former translations diligently compared and reuised, by his Maiesties speciall commandement. -

Survey of Regent Litera1'ure on the New Testament

465 SURVEY OF REGENT LITERA1'URE ON THE NEW TESTAMENT. TEXTUAL CRITICISM.-All who are interested in New Testa ment studies must have hailed with much satisfaction the publication of the first fasciculus of the magnificent work undertaken by Bishop W ordsworth and Mr. White. It is entitled Novum Testamentum Domini Nostri Jesu Ghristi Latine secundum editionem S. Hieronymi ad codicum manu scriptorum fidem recensuit, etc. This part or fascicle con tains thirty-seven pages of explanatory remarks and the whole of the Gospel of St. Matthew. In the explanatory remarks we have an account of the origin of this under taking and of its many hindrances and difficulties; a register and brief identification of the twenty-nine MSS. which the editors have constantly consulted for the gospels, together with some notice of those editions of the Vulgate which have been more or less consulted. In the body of the book the text is printed in columns on the upper part of the page ; across the middle is printed the " Itala " as it stands in the Codex Brixianus, which is supposed to give the nearest approximation to the version used by Jerome in composing the Vulgate; while the lower part of the page is occupied by a record of various readings. Nothing could exceed the beauty of the typography, and no one can fail to recognise the diligence and skill of the editors. "\Vhen complete, the work will be one of the most substantial fruits of English scholarship. The only lack the reader feels is the absence of· material for forming one's own judgment regarding the relative value of the MSS.