Assessment of Travellers Who Return Home Ill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Molecular Evidence of Novel Spotted Fever Group Rickettsia

pathogens Article Molecular Evidence of Novel Spotted Fever Group Rickettsia Species in Amblyomma albolimbatum Ticks from the Shingleback Skink (Tiliqua rugosa) in Southern Western Australia Mythili Tadepalli 1, Gemma Vincent 1, Sze Fui Hii 1, Simon Watharow 2, Stephen Graves 1,3 and John Stenos 1,* 1 Australian Rickettsial Reference Laboratory, University Hospital Geelong, Geelong 3220, Australia; [email protected] (M.T.); [email protected] (G.V.); [email protected] (S.F.H.); [email protected] (S.G.) 2 Reptile Victoria Inc., Melbourne 3035, Australia; [email protected] 3 Department of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Nepean Hospital, NSW Health Pathology, Penrith 2747, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Tick-borne infectious diseases caused by obligate intracellular bacteria of the genus Rick- ettsia are a growing global problem to human and animal health. Surveillance of these pathogens at the wildlife interface is critical to informing public health strategies to limit their impact. In Australia, reptile-associated ticks such as Bothriocroton hydrosauri are the reservoirs for Rickettsia honei, the causative agent of Flinders Island spotted fever. In an effort to gain further insight into the potential for reptile-associated ticks to act as reservoirs for rickettsial infection, Rickettsia-specific PCR screening was performed on 64 Ambylomma albolimbatum ticks taken from shingleback skinks (Tiliqua rugosa) lo- cated in southern Western Australia. PCR screening revealed 92% positivity for rickettsial DNA. PCR Citation: Tadepalli, M.; Vincent, G.; amplification and sequencing of phylogenetically informative rickettsial genes (ompA, ompB, gltA, Hii, S.F.; Watharow, S.; Graves, S.; Stenos, J. -

Distribution of Tick-Borne Diseases in China Xian-Bo Wu1, Ren-Hua Na2, Shan-Shan Wei2, Jin-Song Zhu3 and Hong-Juan Peng2*

Wu et al. Parasites & Vectors 2013, 6:119 http://www.parasitesandvectors.com/content/6/1/119 REVIEW Open Access Distribution of tick-borne diseases in China Xian-Bo Wu1, Ren-Hua Na2, Shan-Shan Wei2, Jin-Song Zhu3 and Hong-Juan Peng2* Abstract As an important contributor to vector-borne diseases in China, in recent years, tick-borne diseases have attracted much attention because of their increasing incidence and consequent significant harm to livestock and human health. The most commonly observed human tick-borne diseases in China include Lyme borreliosis (known as Lyme disease in China), tick-borne encephalitis (known as Forest encephalitis in China), Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (known as Xinjiang hemorrhagic fever in China), Q-fever, tularemia and North-Asia tick-borne spotted fever. In recent years, some emerging tick-borne diseases, such as human monocytic ehrlichiosis, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and a novel bunyavirus infection, have been reported frequently in China. Other tick-borne diseases that are not as frequently reported in China include Colorado fever, oriental spotted fever and piroplasmosis. Detailed information regarding the history, characteristics, and current epidemic status of these human tick-borne diseases in China will be reviewed in this paper. It is clear that greater efforts in government management and research are required for the prevention, control, diagnosis, and treatment of tick-borne diseases, as well as for the control of ticks, in order to decrease the tick-borne disease burden in China. Keywords: Ticks, Tick-borne diseases, Epidemic, China Review (Table 1) [2,4]. Continuous reports of emerging tick-borne Ticks can carry and transmit viruses, bacteria, rickettsia, disease cases in Shandong, Henan, Hebei, Anhui, and spirochetes, protozoans, Chlamydia, Mycoplasma,Bartonia other provinces demonstrate the rise of these diseases bodies, and nematodes [1,2]. -

Parinaud's Oculoglandular Syndrome

Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Case Report Parinaud’s Oculoglandular Syndrome: A Case in an Adult with Flea-Borne Typhus and a Review M. Kevin Dixon 1, Christopher L. Dayton 2 and Gregory M. Anstead 3,4,* 1 Baylor Scott & White Clinic, 800 Scott & White Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA; [email protected] 2 Division of Critical Care, Department of Medicine, University of Texas Health, San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA; [email protected] 3 Medical Service, South Texas Veterans Health Care System, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA 4 Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, University of Texas Health, San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-210-567-4666; Fax: +1-210-567-4670 Received: 7 June 2020; Accepted: 24 July 2020; Published: 29 July 2020 Abstract: Parinaud’s oculoglandular syndrome (POGS) is defined as unilateral granulomatous conjunctivitis and facial lymphadenopathy. The aims of the current study are to describe a case of POGS with uveitis due to flea-borne typhus (FBT) and to present a diagnostic and therapeutic approach to POGS. The patient, a 38-year old man, presented with persistent unilateral eye pain, fever, rash, preauricular and submandibular lymphadenopathy, and laboratory findings of FBT: hyponatremia, elevated transaminase and lactate dehydrogenase levels, thrombocytopenia, and hypoalbuminemia. His condition rapidly improved after starting doxycycline. Soon after hospitalization, he was diagnosed with uveitis, which responded to topical prednisolone. To derive a diagnostic and empiric therapeutic approach to POGS, we reviewed the cases of POGS from its various causes since 1976 to discern epidemiologic clues and determine successful diagnostic techniques and therapies; we found multiple cases due to cat scratch disease (CSD; due to Bartonella henselae) (twelve), tularemia (ten), sporotrichosis (three), Rickettsia conorii (three), R. -

General Signs and Symptoms of Abdominal Diseases

General signs and symptoms of abdominal diseases Dr. Förhécz Zsolt Semmelweis University 3rd Department of Internal Medicine Faculty of Medicine, 3rd Year 2018/2019 1st Semester • For descriptive purposes, the abdomen is divided by imaginary lines crossing at the umbilicus, forming the right upper, right lower, left upper, and left lower quadrants. • Another system divides the abdomen into nine sections. Terms for three of them are commonly used: epigastric, umbilical, and hypogastric, or suprapubic Common or Concerning Symptoms • Indigestion or anorexia • Nausea, vomiting, or hematemesis • Abdominal pain • Dysphagia and/or odynophagia • Change in bowel function • Constipation or diarrhea • Jaundice “How is your appetite?” • Anorexia, nausea, vomiting in many gastrointestinal disorders; and – also in pregnancy, – diabetic ketoacidosis, – adrenal insufficiency, – hypercalcemia, – uremia, – liver disease, – emotional states, – adverse drug reactions – Induced but without nausea in anorexia/ bulimia. • Anorexia is a loss or lack of appetite. • Some patients may not actually vomit but raise esophageal or gastric contents in the absence of nausea or retching, called regurgitation. – in esophageal narrowing from stricture or cancer; also with incompetent gastroesophageal sphincter • Ask about any vomitus or regurgitated material and inspect it yourself if possible!!!! – What color is it? – What does the vomitus smell like? – How much has there been? – Ask specifically if it contains any blood and try to determine how much? • Fecal odor – in small bowel obstruction – or gastrocolic fistula • Gastric juice is clear or mucoid. Small amounts of yellowish or greenish bile are common and have no special significance. • Brownish or blackish vomitus with a “coffee- grounds” appearance suggests blood altered by gastric acid. -

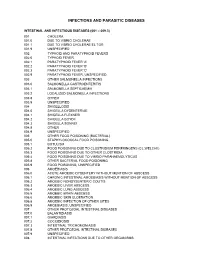

Diagnostic Code Descriptions (ICD9)

INFECTIONS AND PARASITIC DISEASES INTESTINAL AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES (001 – 009.3) 001 CHOLERA 001.0 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE 001.1 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE EL TOR 001.9 UNSPECIFIED 002 TYPHOID AND PARATYPHOID FEVERS 002.0 TYPHOID FEVER 002.1 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'A' 002.2 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'B' 002.3 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'C' 002.9 PARATYPHOID FEVER, UNSPECIFIED 003 OTHER SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.0 SALMONELLA GASTROENTERITIS 003.1 SALMONELLA SEPTICAEMIA 003.2 LOCALIZED SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.8 OTHER 003.9 UNSPECIFIED 004 SHIGELLOSIS 004.0 SHIGELLA DYSENTERIAE 004.1 SHIGELLA FLEXNERI 004.2 SHIGELLA BOYDII 004.3 SHIGELLA SONNEI 004.8 OTHER 004.9 UNSPECIFIED 005 OTHER FOOD POISONING (BACTERIAL) 005.0 STAPHYLOCOCCAL FOOD POISONING 005.1 BOTULISM 005.2 FOOD POISONING DUE TO CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS (CL.WELCHII) 005.3 FOOD POISONING DUE TO OTHER CLOSTRIDIA 005.4 FOOD POISONING DUE TO VIBRIO PARAHAEMOLYTICUS 005.8 OTHER BACTERIAL FOOD POISONING 005.9 FOOD POISONING, UNSPECIFIED 006 AMOEBIASIS 006.0 ACUTE AMOEBIC DYSENTERY WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.1 CHRONIC INTESTINAL AMOEBIASIS WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.2 AMOEBIC NONDYSENTERIC COLITIS 006.3 AMOEBIC LIVER ABSCESS 006.4 AMOEBIC LUNG ABSCESS 006.5 AMOEBIC BRAIN ABSCESS 006.6 AMOEBIC SKIN ULCERATION 006.8 AMOEBIC INFECTION OF OTHER SITES 006.9 AMOEBIASIS, UNSPECIFIED 007 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.0 BALANTIDIASIS 007.1 GIARDIASIS 007.2 COCCIDIOSIS 007.3 INTESTINAL TRICHOMONIASIS 007.8 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.9 UNSPECIFIED 008 INTESTINAL INFECTIONS DUE TO OTHER ORGANISMS -

WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/05 (2006.01) A61P 31/02 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/CA20 14/000 174 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 4 March 2014 (04.03.2014) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (25) Filing Language: English OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (26) Publication Language: English SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, (30) Priority Data: ZW. 13/790,91 1 8 March 2013 (08.03.2013) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant: LABORATOIRE M2 [CA/CA]; 4005-A, rue kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, de la Garlock, Sherbrooke, Quebec J1L 1W9 (CA). GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, (72) Inventors: LEMIRE, Gaetan; 6505, rue de la fougere, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, Sherbrooke, Quebec JIN 3W3 (CA). -

An 8-Year-Old Boy with Fever, Splenomegaly, and Pancytopenia

An 8-Year-Old Boy With Fever, Splenomegaly, and Pancytopenia Rachel Offenbacher, MD,a,b Brad Rybinski, BS,b Tuhina Joseph, DO, MS,a,b Nora Rahmani, MD,a,b Thomas Boucher, BS,b Daniel A. Weiser, MDa,b An 8-year-old boy with no significant past medical history presented to his abstract pediatrician with 5 days of fever, diffuse abdominal pain, and pallor. The pediatrician referred the patient to the emergency department (ED), out of concern for possible malignancy. Initial vital signs indicated fever, tachypnea, and tachycardia. Physical examination was significant for marked abdominal distension, hepatosplenomegaly, and abdominal tenderness in the right upper and lower quadrants. Initial laboratory studies were notable for pancytopenia as well as an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. aThe Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, New York; and bAlbert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis showed massive splenomegaly. The only significant history of travel was immigration from Dr Offenbacher led the writing of the manuscript, recruited various specialists for writing the Albania 10 months before admission. The patient was admitted to a tertiary manuscript, revised all versions of the manuscript, care children’s hospital and was evaluated by hematology–oncology, and was involved in the care of the patient; infectious disease, genetics, and rheumatology subspecialty teams. Our Mr Rybinski contributed to the writing of the multidisciplinary panel of experts will discuss the evaluation of pancytopenia manuscript and critically revised the manuscript; Dr Joseph contributed to the writing of the manuscript, with apparent multiorgan involvement and the diagnosis and appropriate cared for the patient, and was critically revised all management of a rare disease. -

CASE REPORT the PATIENT 33-Year-Old Woman

CASE REPORT THE PATIENT 33-year-old woman SIGNS & SYMPTOMS – 6-day history of fever Katherine Lazet, DO; – Groin pain and swelling Stephanie Rutterbush, MD – Recent hiking trip in St. Vincent Ascension Colorado Health, Evansville, Ind (Dr. Lazet); Munson Healthcare Ostego Memorial Hospital, Lewiston, Mich (Dr. Rutterbush) [email protected] The authors reported no potential conflict of interest THE CASE relevant to this article. A 33-year-old Caucasian woman presented to the emergency department with a 6-day his- tory of fever (103°-104°F) and right groin pain and swelling. Associated symptoms included headache, diarrhea, malaise, weakness, nausea, cough, and anorexia. Upon presentation, she admitted to a recent hike on a bubonic plague–endemic trail in Colorado. Her vital signs were unremarkable, and the physical examination demonstrated normal findings except for tender, erythematous, nonfluctuant right inguinal lymphadenopathy. The patient was admitted for intractable pain and fever and started on intravenous cefoxitin 2 g IV every 8 hours and oral doxycycline 100 mg every 12 hours for pelvic inflammatory disease vs tick- or flea-borne illness. Due to the patient’s recent trip to a plague-infested area, our suspicion for Yersinia pestis infection was high. The patient’s work-up included a nega- tive pregnancy test and urinalysis. A com- FIGURE 1 plete blood count demonstrated a white CT scan from admission blood cell count of 8.6 (4.3-10.5) × 103/UL was revealing with a 3+ left shift and a platelet count of 112 (180-500) × 103/UL. A complete metabolic panel showed hypokalemia and hyponatremia (potassium 2.8 [3.5-5.1] mmol/L and sodium 134 [137-145] mmol/L). -

Protecting Yourself from Zoonotic Infection

PROTECTING YOURSELF FROM ZOONOTIC INFECTION What is a Zoonoses? A zoonotic disease is an infection that is naturally transmitted from vertebrate animals to human beings. Many of these infections are transmitted directly but others are passed via vectors such as mosquitoes or fleas. Not all animal diseases are zoonotic and far more human illnesses result from contact with other humans than from animals. However, it is important for anyone working with animals to be aware of the potential for infection and takes steps to prevent exposure. The following lists some of the more common or severe zoonoses and ways to help protect yourself and others from exposure. IMPORTANT RULES TO HELP YOU AVOID DEVELOPING A SERIOUS ZOONOTIC ILLNESS: Stay current on appropriate vaccinations, such as tetanus and rabies. Wash your hands frequently with antibacterial soap, especially after handling any animal and prior to eating or smoking. Wear long pants and sturdy shoes or boots. Use gloves when handling animals and when cleaning up feces, urine, or vomit. Immediately disinfect scratches and bite wounds thoroughly. Keep scratches or other abrasions covered, especially when cleaning up after animals. Learn safe and humane animal-handling techniques and use proper equipment. Seek assistance when handling animals whose dispositions are questionable. If exposed to tick-infested areas, check your body and clothing frequently. Use tweezers and wear gloves to remove ticks, taking care not to squeeze or puncture the body of the tick. Report any bites or injuries to a supervisor and seek medical treatment as appropriate. Tell your physician that you work closely with animals, and visit him or her regularly. -

Successful Conservative Treatment of Pneumatosis Intestinalis and Portomesenteric Venous Gas in a Patient with Septic Shock

SUCCESSFUL CONSERVATIVE TREATMENT OF PNEUMATOSIS INTESTINALIS AND PORTOMESENTERIC VENOUS GAS IN A PATIENT WITH SEPTIC SHOCK Chen-Te Chou,1,3 Wei-Wen Su,2 and Ran-Chou Chen3,4 1Department of Radiology, Changhua Christian Hospital, Er-Lin branch, 2Department of Gastroenterology, Changhua Christian Hospital, 3Department of Biomedical Imaging and Radiological Science, National Yang-Ming University, and 4Department of Radiology, Taipei City Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan. Pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) and portomesenteric venous gas (PMVG) are alarming radiological findings that signify bowel ischemia. The management of PI and PMVG remain a challenging task because clinicians must balance the potential morbidity associated with unnecessary sur- gery with inevitable mortality if the necrotic bowel is not resected. The combination of PI, portal venous gas, and acidosis typically indicates bowel ischemia and, inevitably, necrosis. We report a patient with PI and PMVG caused by septic shock who completely recovered after conservative treatment. Key Words: bowel ischemia, computed tomography, pneumatosis intestinalis, portal venous gas, portomesenteric venous gas (Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2010;26:105–8) Pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) and portomesenteric CASE PRESENTATION venous gas (PMVG) are alarming radiologic findings that signify bowel ischemia [1]. PI and PMVG are A 78-year-old woman who presented with intermittent often described as an advanced sign of bowel injury, fever for 3 days was referred to the emergency depart- indicating irreversible injury caused by transmural ment of our hospital. The patient had a history of ischemia [2]. Bowel ischemia may be associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, and perforation and has a high mortality rate. Many au- prior cerebral infarct. -

Wildlife Diseases and Humans

Robert G. McLean Chief, Vertebrate Ecology Section Medical Entomology & Ecology Branch WILDLIFE DISEASES Division of Vector-borne Infectious Diseases National Center for Infectious Diseases AND HUMANS Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Fort Collins, Colorado 80522 INTRODUCTION GENERAL PRECAUTIONS Precautions against acquiring fungal diseases, especially histoplasmosis, Diseases of wildlife can cause signifi- Use extreme caution when approach- should be taken when working in cant illness and death to individual ing or handling a wild animal that high-risk sites that contain contami- animals and can significantly affect looks sick or abnormal to guard nated soil or accumulations of animal wildlife populations. Wildlife species against those diseases contracted feces; for example, under large bird can also serve as natural hosts for cer- directly from wildlife. Procedures for roosts or in buildings or caves contain- tain diseases that affect humans (zoo- basic personal hygiene and cleanliness ing bat colonies. Wear protective noses). The disease agents or parasites of equipment are important for any masks to reduce or prevent the inhala- that cause these zoonotic diseases can activity but become a matter of major tion of fungal spores. be contracted from wildlife directly by health concern when handling animals Protection from vector-borne diseases bites or contamination, or indirectly or their products that could be infected in high-risk areas involves personal through the bite of arthropod vectors with disease agents. Some of the measures such as using mosquito or such as mosquitoes, ticks, fleas, and important precautions are: tick repellents, wearing special cloth- mites that have previously fed on an 1. Wear protective clothing, particu- ing, or simply tucking pant cuffs into infected animal. -

THE INTERDEPENDENCE of TROPICAL MEDICINE and GENERAL MEDICINE by GEORGE CHEEVER SIIATTUCK, M.D.Fl INTRODUCTION Water Fever, Cholera, Dysentery, Plague and Lep- Rosy

TheMassachusettsMedicalSociety THE ANNUAL DISCOURSE* THE INTERDEPENDENCE OF TROPICAL MEDICINE AND GENERAL MEDICINE BY GEORGE CHEEVER SIIATTUCK, M.D.fl INTRODUCTION water fever, cholera, dysentery, plague and lep- rosy. Among them are other names which President and Fellows the Massachusetts may Mr. of appear new or such as Medical strange, oroya fever, Society: sodoku, or tsutsugamushi disease. It may be a you so kindly asked me to address surprise to find nearly two pages of references WHENyou on this occasion I assumed that you to rabies, and a few, respectively, to pneumonia, would wish to hear about the subject which has small-pox, tuberculosis, and typhus fever. absorbed most of my attention during the past As interpreted by the "Bulletin" the term seven years, namely, tropical medicine. Suppos- "tropical disease" is inclusive. It covers dis- ing that you might like to know something of eases of limited but not tropical distribution the background of this address I venture to say such as Rocky Mountain fever, as well as mal- that my first, contact with the subject was made adies like smallpox, typhus fever and rabies twenty years ago on a trip to the Par East. which modern hygiene knows how to banish and Later, in 1915, I saw much typhus fever, malaria, which, in consequence, are more likely to be relapsing fever, and papataci fever in Serbia.t found today in backward communities in the In 1921 I joined the Department of Tropical tropics than in highly civilized parts of the Medicine at Harvard, started a Service for Trop- temperate zone.