Applying the Responsibility to Protect to Burma/Myanmar [PDF]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Einzenberger, Rainer

www.ssoar.info Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Einzenberger, Rainer Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Einzenberger, R. (2018). Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State. ASEAS - Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 11(1), 13-34. https:// doi.org/10.14764/10.ASEAS-2018.1-2 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/deed.de Aktuelle Südostasienforschung Current Research on Southeast Asia Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: The Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Rainer Einzenberger ► Einzenberger, R. (2018). Frontier capitalism and politics of dispossession in Myanmar: The case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) nickel mine in Chin State. Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 11(1), 13-34. Since 2010, Myanmar has experienced unprecedented political and economic changes described in the literature as democratic transition or metamorphosis. The aim of this paper is to analyze the strategy of accumulation by dispossession in the frontier areas as a precondition and persistent element of Myanmar’s transition. -

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma)

No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma) May 2009 Watchlist Mission Statement The Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict strives to end violations against children in armed conflicts and to guarantee their rights. As a global network, Watchlist builds partnerships among local, national and international nongovernmental organizations, enhancing mutual capacities and strengths. Working together, we strategically collect and disseminate information on violations against children in conflicts in order to influence key decision-makers to create and implement programs and policies that effectively protect children. Watchlist works within the framework of the provisions adopted in Security Council Resolutions 1261, 1314, 1379, 1460, 1539 and 1612, the principles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and its protocols and other internationally adopted human rights and humanitarian standards. General supervision of Watchlist is provided by a Steering Committee of international nongovernmental organizations known for their work with children and human rights. The views presented in this report do not represent the views of any one organization in the network or the Steering Committee. For further information about Watchlist or specific reports, or to share information about children in a particular conflict situation, please contact: [email protected] www.watchlist.org Photo Credits Cover Photo: UNICEF/NYHQ2006- 1870/Robert Few Please Note: The people represented in the photos in this report are not necessarily themselves victims or survivors of human rights violations or other abuses. No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma) May 2009 Notes on Methodology . Information contained in this report is current through January 1, 2009. -

Child Soldiers in Myanmar: Role of Myanmar Government and Limitations of International Law

Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs Volume 6 Issue 1 June 2018 Child Soldiers in Myanmar: Role of Myanmar Government and Limitations of International Law Prajakta Gupte Follow this and additional works at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, International Law Commons, International Trade Law Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons ISSN: 2168-7951 Recommended Citation Prajakta Gupte, Child Soldiers in Myanmar: Role of Myanmar Government and Limitations of International Law, 6 PENN. ST. J.L. & INT'L AFF. (2018). Available at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia/vol6/iss1/15 The Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs is a joint publication of Penn State’s School of Law and School of International Affairs. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs 2018 VOLUME 6 NO. 1 CHILD SOLDIERS IN MYANMAR: ROLE OF MYANMAR GOVERNMENT AND LIMITATIONS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Prajakta Gupte* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 372 II. BACKGROUND AND HISTORY .................................................... 374 A. Major Political Actors ......................................................... 374 B. Definitions ............................................................................ 376 C. Development of Myanmar’s Society ................................. 377 III. ANALYSIS ...................................................................................... 382 A. Political Stability .................................................................. -

“We Are Like Forgotten People” RIGHTS the Chin People of Burma: Unsafe in Burma, Unprotected in India WATCH

Burma HUMAN “We Are Like Forgotten People” RIGHTS The Chin People of Burma: Unsafe in Burma, Unprotected in India WATCH “We Are Like Forgotten People” The Chin People of Burma: Unsafe in Burma, Unprotected in India Copyright © 2009 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 2-56432-426-5 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org January 2009 2-56432-426-5 “We Are Like Forgotten People” The Chin People of Burma: Unsafe in Burma, Unprotected in India Map of Chin State, Burma, and Mizoram State, India .......................................................... 1 Map of the Original Territory of Ethnic Chin Tribes ............................................................. -

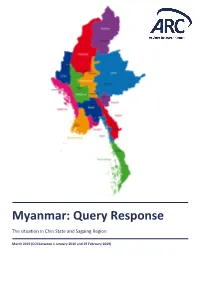

Myanmar: Query Response

Myanmar: Query Response The situation in Chin State and Sagaing Region March 2019 (COI between 1 January 2016 and 19 February 2019) Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author. © Asylum Research Centre, 2019 ARC publications are covered by the Creative Commons License allowing for limited use of ARC publications provided the work is properly credited to ARC, it is for non-commercial use and it is not used for derivative works. ARC does not hold the copyright to the content of third party material included in this report. Reproduction or any use of the images/maps/infographics included in this report is prohibited and permission must be sought directly from the copyright holder(s). Please direct any comments to [email protected] Cover photo: © Volina/shutterstock.com 2 Contents Explanatory Note ............................................................................................................................ 7 Sources and databases consulted ................................................................................................. 13 List of acronyms ............................................................................................................................ 17 Map of Myanmar .......................................................................................................................... 18 Map of Chin State ........................................................................................................................ -

Burma-Initiative

The peace process in Burma’s Chin State: Better human rights protection for the Chin? Rachel Fleming The dominant narrative about Burma1 is of rapid political transition and progress towards peace. The government of Burma has signed Burma-Initiative bilateral ceasefire agreements with 14 out of 17 major ethnic armed groups (EAG) in the country, and is in the process of negotiating a Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement with the ethnic armed groups. This dominant narrative arguably ignores the structural violence at the heart of ongoing human rights violations in the country, including in ceasefire areas. Rachel Fleming asks: Has the current peace process in Burma’s Chin State – a ceasefire area - actually resulted in better human rights protection for the Chin people? In an effort to address this key question, she presents a human rights analysis of the bilateral ceasefire agreements between EAG the Chin National Front and the government, and analyses patterns of human rights violations documented by the Chin Human Rights Organization (CHRO) since January 2012, when Burma's mountainous Chin State the first ceasefire deal was agreed, until the end ©Chin Human Rights Organization of September 2014. Blickpunkte Seite 1 State, resulting in the deaths of 23 Unpacking the dominant trainees from four different EAGs allied with the KIA, including two Corporals narrative from the Chin National Front. The attack Since assuming power in March 2011 has been widely condemned, and poses a following flawed, undemocratic elections significant obstacle for the wider peace in November 2010, Burma’s quasi-civilian process.2 Nonetheless, the various bilat- government under the leadership of eral ceasefire agreements remain in President Thein Sein has been widely effect. -

![Burma [Myanmar] (26 February 2004) Page 1 of 5](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2747/burma-myanmar-26-february-2004-page-1-of-5-4842747.webp)

Burma [Myanmar] (26 February 2004) Page 1 of 5

RIC Query - Burma [Myanmar] (26 February 2004) Page 1 of 5 Burma [Myanmar] Response to MMR04001.ZMI Information Request Number: Date: February 26, 2004 Subject: Burma (Myanmar): Information on the Chin National Front / Chin National Army From: CIS Resource Information Center Keywords: Burma [Myanmar] / Armed resistance movements / Disadvantaged groups / Ethnic conflicts / Ethnic minorities / Political violence / Terrorism Query: Has the Chin National Front (CNF)/Chin National Army (CNA) been involved in what could be considered terrorist or persecutory activities since its inception? Does the Chin National Front or Chin National Army support or receive support from known terrorist groups within Burma, India, Bangladesh, or elsewhere or conduct extraterritorial terrorist activity in those countries? Response: BACKGROUND According to the group's website, the Chin National Front (CNF) was created in March 1988 (CNF). A journalist and expert on ethnic minority groups in Burma wrote in an email to the Resource Information Center (RIC) that in 1987, Chin nationalists took the decision to join an armed coalition against Burma's central government and fight for more autonomy for the various ethnic minority groups represented by the coalition. In 1988, many young Chin fled to the Burma-India border due to pro-democracy unrest in Burma, and some joined the CNF (Journalist 25 Feb 2004). A Thailand-based expert on Burma who writes for JANE'S INTELLIGENCE REVIEW and the FAR EASTERN ECONOMIC REVIEW, http://uscis.gov/graphics/services/asylum/ric/documentation/MMR04001.htm 8/15/05 RIC Query - Burma [Myanmar] (26 February 2004) Page 2 of 5 among others, wrote in an email to the RIC that at first the CNF had no army, but in November 1988 the CNF created the Chin National Army (CNA) (Expert 24 Feb 2004). -

ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions Around Political Violence in Myanmar

ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions around Political Violence in Myanmar Coding political violence in Myanmar poses several methodological challenges given the complexity of the many conflicts in the country. In addition to armed conflict between the military and various ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) in the borderlands, the military in recent years has used nationlist sentiments to wage a campaign of violence and discrimination against Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine state. Further, in the country’s heartland, demonstrations have persisted not just over land and labor issues, but also to demand changes to the military-drafted 2008 constitution. A reference map of the country can be found at the end of this document. Shortly after Myanmar gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1948, several ethnic groups took up arms against the state, demanding equality and the right to self-determination. Divisions between ethnic groups had long been fostered by the colonial practice of ‘divide-and-rule’. This resulted in the center of the country being governed separately from the frontier areas where many ethnic minorities reside. Despite the signing of the Panglong Agreement prior to 1 independence, the failure of the central government to address ethnic concerns led to rebellions by Karen rebels in 1949 and by Kachin rebels in the early 1960s. Other ethnic minorities also took up arms during this period. In March 1962, the military seized power in a coup. It continued with a ‘divide-and-rule’ approach in its dealings with ethnic armed groups, and further adopted a policy of ‘four cuts’, which aimed to eliminate local support for armed groups (Smith, 1991). -

LIST of Terrorist Groups Around the World 1 May 14 K Triad 14 March

LIST of terrorist groups around the world 1 May 14 K Triad 14 March Coalition 14th of December Command 15th of September Liberation Legion 16 January Organization for the Liberation of Tripoli 1920 Revolution Brigades 19th of July Christian Resistance Brigade 1st of May Group 2 April Group 20 December Movement (M-20) 22 May 1948 23 May Democratic Alliance (Algeria) 23rd of September Communist League 28 February Armed Group 28 May Armenian Organization 28s 28th of December Group 2nd of June Movement 31 January People's Front (FP-31) 313 Brigade 313 Brigade (Syria) 4 August National Organization 7 April Libyan Organization 8 March Coalition 9 February 9 May People's Liberation Force A'chik Songna An'pachakgipa Kotok (ASAK) A'chik Tiger Force Aba Cheali Group Abd al-Krim Commandos Abdul Qader Husseini Battalions of the Free Palestine movement Abdullah Azzam Brigades Abstentionist Brigades Abu Baker Martyr Group Abu Bakr Unis Jabr Brigade Abu Hafs al-Masri Brigades Abu Hafs Katibatul al-Ghurba al-Mujahideen Abu Hassan Abu Jaafar al-Mansur Brigades Abu Musa Group Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) Abu Obaida bin Jarrah Brigade Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) Abu Tira (Central Reserve Forces) Achik National Cooperative Army (ANCA) Achik National Liberation Army (ANA) Achik National Volunteer Council (ANVC) Achik National Volunteer Council-B (ANVC-B) Achwan-I-Mushbani Actiefront Nationalistisch Nederland Action Directe Action Front for the Liberation of the Baltic Countries Action Front Nationalist Librium Action Group for Communism Action Group for the Destruction -

Armed Non-State Actors and Landmines Profiles

ANALYSIS PREFACE The Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Treaty (APMBT), signed in Ottawa in 1997, intends to eliminate a whole class of conventional weapons. The fact that over 140 countries have consented to be bound by the Treaty constitutes a remarkable achievement. The progress registered with the putting the Treaty into effect is of great credit to all those involved – governments, civil society and international organizations. Nevertheless, in some of the most seriously mine-affected countries progress has been delayed or even com- promised altogether by the fact that rebel groups that use anti-personnel mines do not consider themselves bound by the commitments of the government in power. Such groups, or non-state actors (NSAs), cannot them- selves become parties to an international Treaty, even if they are willing to agree to its terms. Faced with this potential “show-stopper”, Geneva Call came forward with a revolutionary new approach to engaging NSAs in committing themselves to the substance of the APMBT. Geneva Call designed a Deed of Commitment, to be deposited with the authorities of the Republic and Canton of Geneva, which NSAs can formally adhere to. This Deed of Commitment contains the same obligations as the APMBT. It allows the lead- ers of rebel groups to assume formal obligations and to accept that their performance in implementing those obligations will be monitored by an international body. The success of this approach is illustrated by the case of Sudan. In October 2001, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) agreed to give up their AP mines and signed the Deed of Commitment. -

UNDERSTANDING CHIN POLITICAL PARTICIPATION in MYANMAR By

UNDERSTANDING CHIN POLITICAL PARTICIPATION IN MYANMAR by Peter Swift A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Geography) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN - MADISON 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgements iii Abstract v Glossary vii Chapter One. Introduction 1 Chapter Two. Political context 13 Chapter Three. Methodology 19 Chapter Four. The Chin 25 Chapter Five. Stories of Chin political participation 34 1. University student activism 34 2. Armed resistance 56 3. Party politics 68 4. Christian identity and the Church 75 5. Everyday resistance 85 6. Chin identity and anti-government feelings 86 7. Interest in politics and activist identity 97 Chapter Six. From individual experiences to generalizable patterns 104 1. Identity and socialization 104 2. Networks 112 3. Where people lived 117 4. Mobility 121 5. Sequencing 124 Chapter Seven. Conclusion 127 References 131 iii Acknowledgements I am indebted to the many Chin people who contributed their time and insights to this project. They are too numerous to name and many wish to remain anonymous. Thank you for trusting me and opening your personal lives to me, helping me to understand your world, and introducing me to other Chin. I hope this thesis will be of use to you. I am thankful to Ian Baird for countless conversations over the course of this project as well as comments on drafts of the proposal and thesis, all of which were of invaluable help in the conceptual and practical development of this project. I also thank Matt Turner and Samer Alatout for guidance and advice that helped shape this project over time and for their comments on the near-final thesis.